Venom

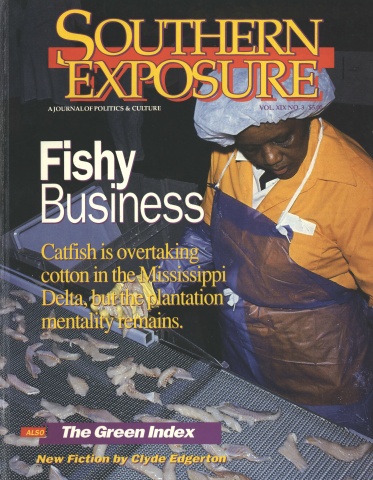

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 3, "Fishy Business." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

There was this incident. It happened to me in the war and I’d never meant to tell anybody about it. Then I flew Liston Edwards down to Wilmington to pick up some canebrake rattlesnakes and on the way back I was explaining it—the war incident—when we crashed and got trapped in the cockpit with the snakes.

I wouldn’t have told him if it hadn’t been for the way he’d started acting toward me earlier that summer. See, Liston had been in the ground war in Vietnam—an Army Ranger—and I’d been in the air war over Laos, a fighter pilot. It was like he couldn’t get enough of trying to compare what he ’d done with what I’d done. Especially when somebody else was around.

I met him a couple of years ago, right after I’d gotten back into flying. I’d just bought the airplane — a 1946 Piper Super Cruiser—and was hanging around Hollis Field on weekends. He and I sort of struck it off. He was a regular out there—crazy about airplanes, but couldn’t get a pilot’s license because he lost an eye right after the war—got hit with the tip of a chain somehow. He wore a black eye patch and had a long black beard. I think he’d gotten an aircraft mechanic’s certificate at one point—I was never clear about it.

Liston and I were the only two vets out there regularly. It was a small airfield. One paved runway. We’d get to talking about the war, but I’d never told him about this particular incident because it had always been a private thing to me. And still is.

The way Liston would get to me is this: He’d ask a question or say a little something that made it seem like the ground war was a whole lot more dangerous than the air war. Very tiny hints, while we were sitting around talking with some of the guys. I can’t even think of a good example.... Oh yes, he’d say something about fighter pilots flying home to rib-eye steaks and comfortable beds every night. Stuff like that. But he wouldn’t stay on it—so you might have a chance to respond. He’d just skim over it and leave you a little bit frustrated. Sometimes I felt I was like pulling away from him when we’d talk about the war, like I was feinting, drawing back from a left hook—drawing back from the power in his eye. I didn’t want to feel that way. I didn’t like it. I wanted him to see that I was as strong as him.

But having been a soldier—we called them “grunts”—we never really knew what the air war was actually like, and to make it worse, the stories I told were never quite as hairy as his. I mean he’d seen blood and actually touched the enemy—hand-to-hand combat, and all that. But I’d never ejected or anything like that or even had my airplane hit. I could talk about ejection seat training, but not the real thing. And I hadn’t planned to tell him about my war incident. But still, there at the beginning of summer, for the first time in twenty years, I was getting a chance to tell some stories about the war. I was remembering.

I guess I always had it in the back of my mind that if I told Liston about this incident, and changed the ending around a little bit, it would even things up because he’d have a hard time topping it. So when I had my back against the wall, just before the crash, I told it to him, part false. And then, afterwards, all true.

So, about the snakes.

On a cold Wednesday morning in November we strapped in, seat belts only — no shoulder harnesses in a Super Cruiser. There’s one seat up front for the pilot, one in back. I looked in my little wide-angle rearview mirror and saw Liston—broad shouldered, wearing his eye patch, his long black beard streaked with gray. He was wearing a skull cap. Behind him on top of the baggage compartment was a small empty wooden cage with a heavy screened front, a hinged top, and through the latch—a small notched stick.

The Super Cruiser is a narrow, light little airplane. The interior of mine was very nice—with red padded seats, part leather, part tough cotton fabric, kind of a red plaid in some places. Gerald McCullers, the fellow who owned her before me, had her rebuilt inside and out and had kept her inspected, as far as I knew.

We took off and leveled at 1,500 feet. The air was very smooth, the visibility was great, and the trees cast long shadows. In some places the frost sparkled. We flew at 1,500 feet mostly, dropped down to 500 feet once in a while, and didn’t say much on the trip down.

I’d had the airplane for about eight months, named her Trudy, and felt confident flying her. She was simple to operate, and clean. She flew low and slow and was a lot of fun.

We met the snake guy at the airport in Wilmington and he took us out to his truck. Little man with a mustache and big hands. He shook the four rattlesnakes from his cage down into Liston’s cage. Two large ones, a medium, and a small. The two big ones were over four feet long and bigger than my wrist. As they were all dropped together into the box, their rattles started up, a fuzzy buzzing, then died down after they got settled.

They’re all feisty, the guy said. I ain’t had them long. He looked at me. You ever seen fangs close up? Nope.

He looked in his truck bed, found a stick with a metal hook on the end, slid it around the small rattlesnake and pulled it up. All the rattles started up again. He dropped the snake on the ground, pinned the head with the hook, reached down slowly and took hold behind the head and picked it up. It twirled, found his arm and wrapped around it. He pressed the hook into the snake’s mouth and opened it wide in such a way that two tiny white nipples dangled. He pressed harder. Two small, white, sharp, slightly curved bone-needles emerged, one dripping.

Piece of work, ain’t it?

Sure is, I said.

He dropped the snake back in with the others. The rattles started up, sounding like bees.

Liston stuck the little stick back through the latch, then paid the guy ninety dollars.

We put the cage on the baggage compartment lid behind Liston’s head and took off.

I had gotten a kick out of the look on people’s faces when I told about planning this trip, about Liston being an Army Ranger who had been a snake handler and all that. I never once mentioned his resentment of my being a pilot, and I’d never worried once about anything going wrong with the airplane engine.

On the way back we started talking some.

Say you got shot at right much over there? he asked. He’d asked that before.

Oh yeah, I said. But I’d have to look at the records to really know, you know, exactly which days and all. But if we were putting in ordnance at places like Miguia, the Dog’s Head, or the H in the river, we about always got shot at.

Say you never got hit?

Never got hit. But I was on my flight lead’s wing when he got hit. (This is when I started my story.) Did he go in?

Yeah, he did.

Got killed?

Yeah.

And here’s where I decided to go on and tell about the whole incident if he kept asking — leaving out what happened in the end, the true ending. I mean, Liston had just mentioned to the snake pilot that I was a former fighter pilot and had stayed, as he put it, high and dry during the war.

I guess we were about fifteen miles south of Horseshoe Lake. I looked in the rearview mirror at the stick in the latch.

Wadn’t it hard, said Liston, flying around up there by yourself, not being able to rape something or kill somebody when one of your buddies got killed? You know.

We were able to shoot up some stuff.

What?

Oh. Whatever was available. A jackass.

A jackass? Yeah. Find something on the roads, I said.

I’d never told anybody about the donkey. I’d told people about the people. I’d told that part of it in the bar right after I did it. We told about those things. It was just shooting gooks.

We got quiet and I was thinking about how I could tell Liston about Lew, about me and Lew. Our friendship. I decided I couldn’t explain that. But I went ahead and started telling him about the incident, right up to the end, including the false ending.

Lew was my best buddy. We’d met in Bangkok on the way to Nakong Phanom where we were stationed. I’d actually met him in the Philippines during survival training but we hadn’t had a chance to talk until in a bar in Bangkok. Lew looked like a vulture sitting on a limb—no butt, stooped shoulders, long neck, big nose, cowlick in the top back of his head. He was loose-jointed, and when he’d had a few, his nose got red. Sometime she’d come over to my room around midnight with a six pack of tall Blue Ribbons and a flip-top pack of Winstons and we’d sit and talk for a couple of hours.

All of a sudden, about ten miles south of Horseshoe Lake, what you hope and believe in your heart will never happen, happened.

Engine failure. A cylinder head had separated and the cylinder cracked. At least that’s what the investigation said. It sounded like a car engine does when you lose a muffler. The engine was suddenly very loud and I felt extra heat on my knees. I first thought the muffler had burst—which would have been manageable—but right after the noise started, the rpm began dropping. I grabbed the throttle, thinking it had slipped back somehow, but it was stationary. The throttle was stationary—right where it was supposed to be—but the rpm was dropping. The needle looked like the secondhand on a clock going backwards. It was like holding the accelerator on the floorboard while the car slows down and keeps slowing down. Then there was a powerful vibration and the propeller froze.

Black smoke was coming through the heating vent. I bent over and closed it.

We had been in a left bank above Miguia Pass, when Lew’s nose dipped funny—a quick pitch down, then up—and at the same time I saw out of the corner of my eye something tear loose from the tail end of his aircraft.

Fox two, I think I’m hit, he says.

That’s affirmative. I’ll drop back and check it out. I pulled back on my power. He was out to my left. When I was behind him, I saw that his left elevator was gone.

What’s wrong? asked Liston from the back seat. Very casual. Very calm.

Through my mind flashed what I’d always planned to say to a passenger if this happened: that I needed to practice a precautionary landing. That it’d be fun and not to worry. But I knew that wouldn’t work now.

I don’t know what’s wrong, I said. Something blew. We’ll have to put her down somewhere. I was trying to sound calm. I made my radio call. Mayday, Mayday, Mayday. Piper 2662 Charlie. Engine failure. Landing about nine miles south of Horseshoe Lake. Mayday, Mayday, Mayday. Piper 2662 Charlie. Engine failure. Landing about nine miles south of Horseshoe Lake.

No answer.

I pulled the throttle all the way back to idle and turned off the fuel selector handles. We were at 1,300 feet. Ground elevation was 400. Step One: set up a glide speed of 70 knots. Two: look for a field or road. There was a straight country road to the left and behind me—no cars on it. Well, one big truck. Power lines, though. All over. No way. I thought about that cage of snakes—the latch.

I can’t control it, he said.

You have to punch, Lew. Your elevator is gone. My insides were a dull red and yellow and my heart had stopped so still I couldn’t get my breath. His aircraft was starting a slow roll to the left. I dropped back farther.

I got to punch, he said. He was trailing smoke.

Get out. Now. It might blow. I moved out wide.

He shot out vertically, away from me and immediately way back behind me. I called for Search and Rescue. They would take at least forty-five minutes to get there. I started a hard bank to the left, over his plane which was going down now, inverted. I had my eye on him, a dot, and then his parachute blossomed bright white and orange, and as I circled back he was not far below me and almost sitting still, the green jungle drifting along below him, like a hot-air balloon out over some green North Carolina woods. Then there was the flash of his plane exploding into a low mountain about thirty kilometers east. Black smoke boiling up.

Old Lew. Lew Byrd. Foo Bird, we called him. The Mustard Man. He’d put mustard on his head and jump up off the bar so that his head hit the ceiling and left a yellow spot. Two ten, the bartender would laugh, put his hand over his rotten teeth and then say, Captain Foo Bird you break your neck next time. I tell you, you break your neck.

There were a bunch of good Lew stories.

And he was the one I'd cried in front of when I got the letter from Marie saying she was getting married. That she was sorry. That we’d had some great times together. He had gotten up and come over and sat beside me and put his arm around me. That’s all. No talking about that one.

One of our best gigs was stealing an army general’s jeep and getting it loaded on a C-130 and flown to Bangkok.

Straight ahead were three pastures. I’d go for the pastures. I checked my gauges. The oil pressure was zero.

Mayday, Mayday, Mayday. Piper 2662 Charlie. Engine failure. Landing about nine miles south of Horseshoe Lake in largest of three pastures together. Mayday, Mayday, Mayday. Piper 2662 Charlie. Engine failure. Landing about nine miles south of Horseshoe Lake in largest of three pastures. Roger, Piper 62 Charlie. This is Cessna 4723 Echo. How do you copy?

Loud and clear, but I’ve lost my engine and I’m landing in a pasture nine or ten miles south of Horseshoe Lake. Please launch a search and rescue. Copy?

23 Echo. Copy.

Shit, this ought to be interesting, said Liston. I felt him shift his weight around. The plane is so small and light you can feel people move around behind you. I was holding 70 knots. The altimeter read 900 feet. There was a lot of heat coming through the firewall. I would have to shut down the electrical system. A fire is the worse thing that can happen. I needed to concentrate on getting to those pastures out there in front of me. I had enough altitude to glide in for a landing. It appeared that I had enough altitude.

Lew was getting his radio out of his vest when I flew past him as slowly as I could, but not too close. They were firing from below like nobody’s business now, smelling blood. Black and white flack bursts. They were firing their thirty sevens, fifty-sevens, and eighty-fives. He was going to land in the jungle to the east of the Trail.

I saw him bring his radio up to his mouth. Then through my earphones I hear him say, Which way is a safe area?

Hell, I knew there wasn’t any safe area. To the east I said. The way you’re drifting. Behind you. Steer it toward the sun as much as you can. That would get him away from the Trail as far as possible.

But it was morning and they’d have all day to find him.

He went in. I marked the spot. Two lines of bomb craters and a river, three or four kilometers off the Trail. And I could see them rushing down the trail on foot and on bicycles and I was getting fire from at least four, maybe six positions. I circled wide, dropping the lowest I'd ever been out there, and made a pass with tracers streaking across my nose, my heart and liver in my throat. I dropped half my bomb load and climbed up and looked back but the bombs had landed long and to the west. I had been too high. I hadn’t gotten right in on them like I should have. I needed to get all the way down and strafe if I was going to do any good. I wondered if Lew had seen me. Then he was on the radio again, talking to me from the ground— coming in clear. Fox two, this is Fox lead, he said. How do you read?

I tried to keep my voice calm and pitched low. Loud and clear, I said. Hide. I've launched the SAR. They’ll be right here. I’ll sanitize the area between you and the Trail. Hang in there. The SAR will be right out. We’ll get you out. I tried to sound calm. I’ll keep them off you, Lew.

I think my back’s broke, he said.

There were four, not three pastures up there. The biggest was nearest, and the one I’d chosen to shoot for. Electrical wires? No—no telephone poles anywhere. Roads? Where was the nearest road?—for help. Way ahead there, to the west.

Liston, I said, I’m shutting down the engine. My voice was not as calm as I wanted it to be.

I realized I was a tad low. The last thing you want. The head wind was strong. I was going very slow over the ground and sinking. I had to make that pasture. Airspeed was 70. Best glide angle.

It was very quiet. Just the wind.

I was afraid we might be short. Just barely short. But maybe not.

Master switch, off.

Out to the right was an old barn, but I didn’t see a house. Get it back to 60 knots now. Land slow. Fox lead, I said to Lew, pull in your parachute, bury it if you can. Hide. Turn off your radio until you need it. You got a good radio. I can hear you clear.

An eighty-five burst went off no more than a hundred yards at my eleven o’clock. A burst of thirty-sevens ahead and below. I was going to be down there in the jungle with him if l didn’t watch out. I saw that I was going to be down there with him. I just knew it. No need for both of us to be down there. I didn’t have the fuel to wait for the SAR. I could wait a little longer if I didn’t make any more passes, and talk to Lew. Keep him calm instead of going back in. But I had told him I was going back in.

I can hear them, says Lew. They’re to my west. Goddamn, I broke my back. They’ re coming. Get down here!

I was at 9,000 feet, level.

He started whispering. I can hear them, he said over and over.

Right here is where I went about crazy. In order to be effective with strafing I’d have to get low enough to be in range of the twenty-threes. I could surely do him more good up high talking to him, I figured. It’s safer and it will make him feel better for me to be up here where I can talk to him. But if he does get out, he won’t like it that I didn’t go back in, and he’ll tell everybody.

Just before our engine failure I had told Liston that I went back in for Lew—four passes, strafing — and killed a lot of troops and a donkey and that Lew never got out.

The ground is flying under me. It’s so quiet.

I’ve got to stretch the glide over that barbed wire. Nose up. Nose up. Nose up. I’m going to be short of that barbed wire fence. I read about a guy bouncing over a ditch. I’ll hit and bounce over the fence. I push the nose over, hard, hit the ground hard with the main gear. Bounce. The damned main gear catches the top two strands of barbed wire. My head snap-bangs forward and back off the instrument panel. The airplane flips upside down and we land on the top, tail first, in the pasture. I’m watching the ground shoot out from behind us, right there at our heads, going away from us as we skid along backwards, upside down on the ground, and I’m watching dirt and grass fly away from us, wondering when we might stop. All the baggage from the baggage compartment—thermal blanket, ropes, tie-down stobs, oil cans, sponges, maps, life preservers, flashlights, rags — is flying every which way and I know I’ve been hit hard on the head. I can see where we’ve been, how we’re scraping a swath along the grassy ground.

We slide to a stop.

I’m hanging by my seat belt, upside down.

The first sound I hear is leaking fuel, and then, all around my head, the dry-bones, buzzing sound of the rattles. I smell the fuel and a burning electric smoke. I am so struck with those rattles in my ears that I cannot get my breath and I’m trying to decide if it’s knocked out of me or what when it comes in a rush and I gasp, keeping as still as I can.

The rearview mirror is gone.

The rattles stop. There is the midsection of one of the big snakes, moving — the rest of him covered by a thermal blanket and a life preserver—a yellowish streak down his back through the designs. There’s another one’s head over there. No, wait, it’s the same one.

You okay, Liston? I turn my head slowly, very slowly and look. Liston is hanging still. I want to scream for somebody to come and solve all this. Through Liston’s long beard hanging upward I see that the eye patch is gone. The eyelid is closed on an empty socket. It’s sunk way in. Blood bubbles up from his nose.

I need to get out, to release the seat belt, fall into the ceiling and get out, or maybe I can scare the snakes out first or something. But it’s cold outside. They’ll stay in here.

Goddamn shit almighty, says Liston. I thought we were supposed to land.

We did.

What the hell did my head hit?

I don’t know. Are you okay?

I hit my head. Shouldn’t we get out of this thing?

Well, yeah, I guess so, but those snakes are all around in here. You didn’t have it latched right. Goddamn almighty, my nose is broke. What happened? I thought we were landing?

We hit the fence. Flipped.

We can throw the snakes out.

Can you see them?

I can see three of them. All but the medium one.

I move my head very slowly and look at the door. That door is jammed, I say. Bad. I can tell by looking at it. I don’t especially want to reach over there until we figure out where the snakes are. You sure had a lot of junk in that baggage compartment, says Liston.

I know. Well if you can get the window open, I’ll try to throw these three out.

That looks jammed too. Where are they? — the snakes.

Two of them are right behind your right ear. Coiled. You probably shouldn’t be moving your head too much. Until I tell you to. I ’ll tell you what. I’ll catch them and choke them. Don’t move toward that window, yet. Okay. In just a second you need to start moving your head back and forth real slow so that’ll get their attention and they’ll look away from me and I can grab them. I need to grab both at the same time. Go ahead. Now. Start moving your head back and forth.... A little faster than that.

You sure about this? I say.

Yep. Where’s the other one — the one you can see?

Back here in the corner. I think he’s injured or something. He ain’t coiled. Move your head just a little faster.

I do, and the rattles start up—one, then the other. I might could do this a little better, he says, if I wadn’t hanging upside down.

There is a rushing sweep sound.

Got ‘em. This will be just a minute.... Just another minute here.

Fuel is leaking out of both wing tanks onto the ground, puddling, and the grass grows up through it like a miniature swampland iced-over.

I heard the fire before I saw or felt it. It was cracking in the engine, like a frying pan.

What had happened was that when they got to Lew they started shooting him and he started screaming over his radio: I'm hit. I’m hit. Jim. I'm hit. And I could hear through the earphones the tat, tat, rat, tat, tat-tat of the guns shooting old Lew. He was screaming and his voice was like a rabbit in a cage squealing. The rat, tat-tat, like little toy guns, sounding little and far away through the earphones tight to my ears, Lew’s thumb holding down the transmit button while they shot him over and over and over again. And I was way up there above him, not down there amongst it all, fighting it out.

We’re on fire, Liston. The fuel tanks will blow. We got to get out.

Calm down.

Calm down!? Shit man.

I hear his seatbelt buckle snap open. Then he’s down and at the window with his fist. My God, he’s trying to get out before me.

I kick at the window as hard as I can. The plexiglass pops out clean. He’s starting through it. Before me. I’m after my seat belt buckle. But his leg is caught somewhere. He’s hung up somehow. He can’t get anything but his arms through the window. The rattle buzzes, the head comes up like a sudden broom handle and pops forward. I feel it just above my knee like the pop in the end of your finger when the nurse takes blood, but sharper and hotter.

Help, I scream. Goddamn. I’m bit.

I unsnap my belt buckle, fall on my head, move away from the snake. Liston is grunting, trying to get his leg loose. I go scrambling, pulling through the little window opening ahead of him—catching my shoulder, then working loose, then out. It seems like he might be screaming. I feel the bite burning, and the wet fuel on my bare skin at my waist in back where my shirttail must be out. This odd thought comes—I must tuck in my shirttail. Tuck in your shirttail, Jim. You don’t want to go to school looking like that. Then I’ve rolled away and I’m sitting there watching and here comes Liston through the little opening, his one eye straining at me as he pulls through, clear, the fire suddenly rippling across the ground from the engine, going WOOSH, up all around him. He’s gone—behind the fire... then he comes rolling out, splashing through the fuel. He’s on fire. I stand, get to him. He’s rolling slowly, getting the fire out. Except the skull cap on his head is still burning. I fall on him, burn myself some, grab him under the arms and pull him away, smoking and black. He gets up to his knees. I sit down and then vomit.

You got bit? he’s saying.

Yes. Yes.

We need to work on it, he says. He’s on his hands and knees and his beard is completely gone and it flashes through my head that he is somebody else — somebody come to help. A big man with horrible sunburn covered with soot.

Yeah, but we got to move back from the fire, I say. I think to myself that I want him to see me thinking and acting in the face of danger, after being wounded. It’s something he will be able to tell people about me.

We move away. He’s crawling and I’m sliding on my butt and hands backwards. When I stop he crawls to me, pushes up my trousers leg and starts working on my leg. You got to relax, he says. Can’t have venom pumping all through you.

Will it kill me?

I doubt it. His talking is very bubbly.

I lean back on the ground, look up into the cold blue sky without a thing up there but the airy blueness and the hard fast clear pulsing of the transparent veins in my eyes.

In a few seconds there was a smell—it had to be his burnt hair and flesh.

Then he started shaking really, really bad, tried to stand, and collapsed on me. I got myself out from under him. His face was in the dirt so I rolled him onto his back. I wondered where I could find some kind of salve to put on his burns. Oil from the engine when it stopped burning maybe. He looked horrible. He was black and pink. I looked at his stomach. It had some of his shirt left on it. He was holding his stomach very still like actors do when they play dead on stage. I wondered why Liston would want to be doing that— of all things. I turned and looked across the pasture at the strands of barbed wire and our path across the ground.

From the airplane, black clouds of smoke rolled up into the sky like they were in a hurry to get away. Somehow he’d gotten my trouser leg up and the bite was like a red tennis ball with two needle holes. I got my pocket knife out and cut at it and sucked until I vomited again.

Then I lay back beside him and while I waited for help I told him what really happened, the truth, the true ending to the incident in the war.

Tags

Clyde Edgerton

Clyde Edgerton is the author of Raney, Killer Diller, Walking Across Egypt and The Floatplane Notebooks. (1991)