This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 3, "Fishy Business." Find more from that issue here.

Woodland, N.C.—In front of Town Hall, 50 residents wait out an executive session of their town board in the cool air of early summer. They had packed the meeting hall to protest plans to build a hazardous waste incinerator in town, but the board had ordered the room cleared when the debate grew heated.

Suddenly, someone shouts, “Bill Jones is being dragged out!” A curious crowd surges to the back of the building in time to see one of their neighbors who had refused to leave the meeting being dragged to a police car.

Carrie Ward shakes her head and frowns as police force Jones into the waiting cruiser. The hazardous waste incinerator, she says, has brought nothing but trouble to the town of 850 people where she was born. “Woodland was a friendly place and we never had no problems like this here. It was neighbor helping neighbor. Now this thing come in here and done messed up the neighborhood. Strangers come in here and divide us.”

The strangers are officials from ThermalKEM, a German-owned corporation that wants to bum 100 million pounds of hazardous wastes each year near the Virginia border in rural Northampton County. The company says its $70 million incinerator and landfill will provide hundreds of jobs and millions of tax dollars to an area suffering from high unemployment and few social services.

Despite such promises of plenty, most Northampton residents oppose the incinerator. ThermalKEM has a disturbing record of safety mishaps, they point out, and burning toxic debris will harm their children and scare away other industries. “It sounds good for the town,” says one Woodland resident, “but if you kill everybody, you won’t need no town.”

Yet the widespread community opposition has failed to stop ThermalKEM. For the past year, company and state officials have quietly worked behind the scenes, using their money and influence to convince county leaders to ignore the health risks and accept the incinerator. ThermalKEM has offered free trips to county commissioners, wooed local ministers, and tossed in promises of a new recreation area, better roads, and improved health care.

The promise of jobs and county services has been especially effective in the black community, which suffers from chronic unemployment and poverty. Northampton has been deeply divided between rich and poor, black and white, for more than two centuries, and its history of misery and mistrust makes it particularly vulnerable to a corporation like ThermalKEM. In essence, say some black leaders, the company strategy amounts to little more than environmental blackmail—an effort by those who profit from toxic waste to divide and conquer poor black communities.

“The conventional wisdom now is that you can bribe people,” says State Senator Frank Ballance, who represents Northampton County. “I don’t mean the kind of normal bribe where you say, ‘Take this money under the table.’ I mean telling people, ‘We’re going to build you some roads and give you a school and give you $3.5 million in taxes.’ It’s difficult to resist when you’re poor.” “Companies like ThermalKEM thrive on counties with a majority black population,” agrees Bennett Taylor, president of the local NAACP chapter. “They think blacks are not really important, so it’s not important that the incinerator will raise disease rates. This is a poor county already. ThermalKEM says, ‘Here’s a few dollars to bring your county up.’ Some citizens feel the way I do — that a person’s health is more important.”

As a veteran union activist at the J .P. Stevens plant in nearby Roanoke Rapids, Taylor has grown suspicious of corporate promises. But ThermalKEM’s strategy has met far better success among black leaders who are still tied to the old culture of peanuts and paternalism—and among black contractors hoping to cash in on a piece of the action from new high-tech industries.

Slavery’s Legacy

Route 158 bisects Northampton County, rolling over the Roanoke River, cutting across flat peanut fields, running past white-frame farm houses, through the county seat of Jackson and on into Hertford County. The road is part of the Historic Albemarle Tour Highway, marked with placards commemorating the deeds of Confederate heroes like “Boy” Colonel Henry K. Burgwyn and General Matt Ransom.

No historical markers tell of the painful legacy of slavery, but the signs remain. Between the prosperous fields and large homes sit gray shacks, unprotected from wind and rain. Old folks rock in the damp heat on the porch; younger ones lean on rusting cars in the yard. A store on 158 advertises bingo candles and “hot lottery dream books”—a quick fix to the poverty that has been cultivated like the soil for hundreds of years.

Numbers bear witness to the continuity between the county’s plantation past and impoverished present. According to census figures, Northampton was 60 percent black in 1820. Almost all were slaves, and even after emancipation most continued to work on farms owned by whites. Black residents gained influence within their own communities as ministers and teachers, but whites still dominated county politics.

Little has changed in the past 170 years. According to the 1990 census, black residents still make up 60 percent of the population. The county remains primarily agricultural, with unemployment above 10 percent among blacks. Per capita income is below the state average, education is substandard, and infant mortality is high. One in four residents lives in poverty, and one in six lives in housing without adequate plumbing. Despite the black majority, only one of five county commissioners is black.

Black leaders insist that the sharp divisions between the haves and have-nots is no accident. For years, they say, white farmers have intentionally discouraged industry from setting up shop in Northampton, trapping blacks in low paying farm jobs.

“The way they’d protect these farmers was to keep these poor blacks out of jobs and sitting around waiting on the corner,” says State Senator Frank Ballance. “So when the farmer comes by and says, ‘I have a few potatoes to dig. I’ll pay you a dollar and a half an hour,’ then those people would have to accept.”

Ballance opposes the incinerator, but other black leaders, angered by the calculated failure of whites to attract industry to Northampton, support the ThermalKEM project. After all, they say, white people have never cared about us before. Why should we trust them now when they claim this incinerator is a bad thing?

“Who has the gold has control,” says Vernon Kee, a building contractor and the lone black on the county commission. “And black folks don’t have the gold in Northampton County. It comes right back to the old white establishment. They don’t want industry, but they don’t want to pay more property taxes either.”

Like many other black leaders, Kee supports the incinerator, insisting it will bring much-needed jobs to the area. To ensure his support, ThermalKEM flew him and two other commissioners to visit its incinerator in Rock Hill, South Carolina. The company also held a training session at a closed-door meeting to teach commissioners how to respond to public opposition.

A few days after the session, Kee assured residents that he would “vote the wishes of the people.” Six weeks later, he voted to invite ThermalKEM to burn toxic wastes in Northampton County.

Arsenic and Race

The controversy over the incinerator heated up in 1989, the deadline set by the Environmental Protection Agency for states to find ways to dispose of their own hazardous wastes or risk losing federal funds. Alabama and South Carolina, tired of serving as regional dumping grounds, also threatened to close their landfills to out-of-state wastes. Faced with these dual pressures, North Carolina signed a regional disposal agreement with four other states and pledged to build its own incinerator.

North Carolina chose ThermalKEM to build the waste furnace, and together they launched a public relations campaign to find a site. Despite the promise of jobs and revenues, it turned out to be a tough sell. In county after county, residents mobilized to oppose the incinerator. In Granville County, angry residents bulldozed Governor James Martin in effigy. Opponents also bought up land designated for the incinerator and sold it off in tiny parcels to force the state to negotiate with thousands of owners.

Citizens had good reason to protest. According to a national survey of 27 incinerators by the Citizen’s Clearinghouse on Hazardous Waste, every facility has experienced serious accidents—including spills, leaks, equipment failures, fires, and explosions. Residents who live nearby have suffered respiratory problems and higher than average rates of cancer. Many workers have contracted neurological diseases, and some have died from explosions or exposure to gases. ThermalKEM itself has a poor safety record at its Rock Hill incinerator. One hundred employees had to be evacuated after an explosion in 1988, and two workers were hospitalized. State inspectors cited ThermalKEM for a long list of safety violations in 1989 and 1990, including evidence that the firm released excessive levels of arsenic and chromium into the community.

Studies indicate that incinerators hurt the economy as well as the environment. “Commercial hazardous waste management facilities do not bring about industrial growth,” says William Sanjour, a policy analyst with the EPA. “Rather, they tend to depress any area in which they are located, from the point of view of economics, public health, the environment, and morale.” After surveying communities with incinerators, Sanjour concluded that the facilities generally drive away new industry, employ fewer than 100 workers, and lower property values.

Faced with a threat to their health and economic well-being, a total of 19 counties in North Carolina rejected the ThermalKEM incinerator. Blistered by the political heat, state officials decided the incinerator was too hot to handle and told the company to find a site for the facility on its own. ThermalKEM already had an option on 415 acres of land in Northampton County, but it needed the go-ahead from local officials. Realizing that public overtures would only spark more citizen protests, the company set out to quietly entice county officials to “invite” the incinerator into the community. “It looked like the state had hit a dead end, so we were going to have to go and get a volunteer county,” says George White, a ThermalKEM spokesman. He insists, however, that the company “will not come into an area where the leadership and the people don’t want it there. The leadership in the county and individuals and groups in the county call the shots.”

Yet ThermalKEM left little to chance. The company did its homework, apparently conducting extensive background checks on each county commissioner. Commissioner Jasper Eley says he was approached by ThermalKEM executive Mark Taylor. “He knew more about me than I did myself,” says Eley.

According to Eley, Taylor did more than tell him how good the incinerator would be for the community — he also offered to get a job for the commissioner’s son, who is a toxicologist. “When we get located in Northampton County and he wants a nice job making $65,000 a year,” Taylor told Eley, “tell him to come and see me.” Taylor denies the conversation ever took place.

The company promised the incinerator would create 250 jobs and $3.5 million in fees and taxes—half the county’s current operating budget. According to a company letter, Governor Martin also invited county commissioners to a breakfast in Raleigh, where he promised to “provide a new county recreation area, new and improved roads, and better county health services.” There was also talk of forgiving the county’s large school debt.

“A Life and Death Issue”

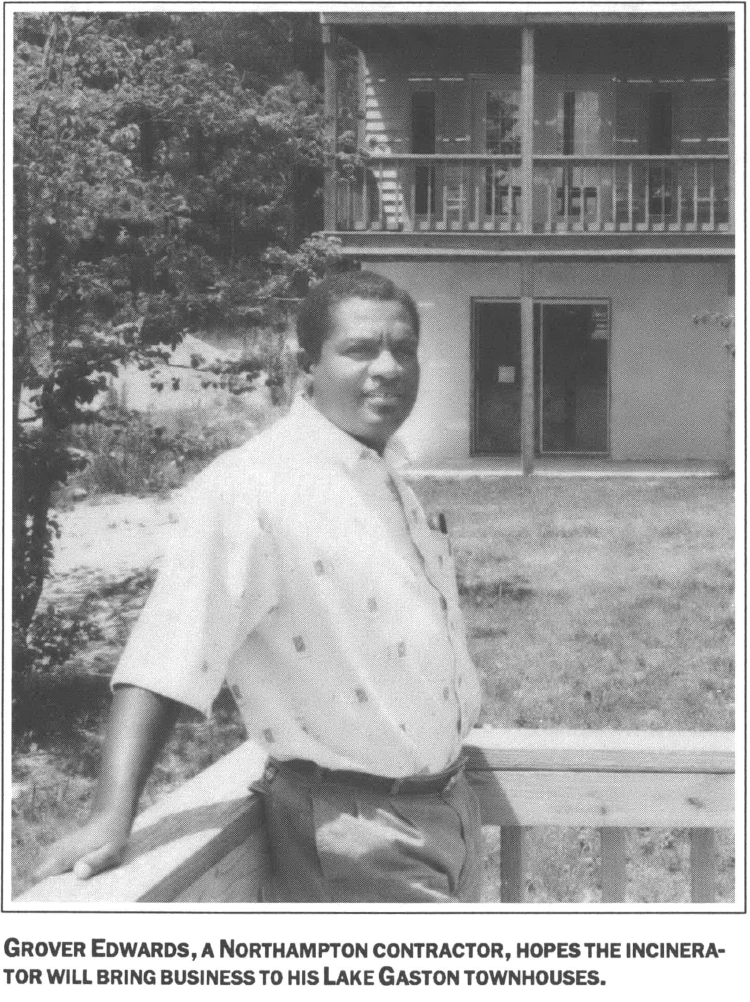

The promise of jobs and services pleases Grover Edwards, a Northampton developer and former school board member. “If the county is going to do something for the governor of North Carolina,” Edwards says with a smile, “then you might want to take advantage of that wish list while it’s being passed around.”

From the start, ThermalKEM has focused on winning the support of Edwards and other prominent members of the black community. The company flew Edwards to Rock Hill, where he says he was impressed by the town’s prosperity.

“It’s a booming town—banks, churches, a beautiful place, wages are good,” says Edwards as he walks out on the unfinished wood dock of a townhouse development he’s building on Lake Gaston. The incinerator will be good for his business, he adds—more jobs mean a greater demand for houses.

Charles Tyner also got a free trip to Rock Hill, courtesy of ThermalKEM. An elementary school principal and minister, Tyner says the trip helped convince him that the incinerator “would benefit Northampton County... with this problem with finances.”

The company attention appears to have paid off: Many black leaders either favor the incinerator or are remaining neutral. In a county where many residents have scant education and rely on local leaders to inform them on important issues, ThermalKEM’s campaign has been an effective influence on the ministers and teachers who sway community opinion.

The campaign has been so effective, in fact, that many black ministers appear uninterested in learning about the health and economic risks of the incinerator. Ben Chavis, a prominent black minister with the Commission on Racial Justice of the United Church of Christ, produced a study showing that toxic waste facilities often wind up in minority communities. When he visited Northampton County and invited 50 local clergy to a luncheon to discuss his study, however, only a handful showed up.

After the luncheon, Chavis phoned the ministers who failed to attend. “How can you lecture people every Sunday with just a little bit of information?” he demanded. “This is a life and death issue.” Some black leaders aren’t surprised that ThermalKEM has tried so hard to influence them. James Boone, a local organizer for the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union, says he has seen J.P. Stevens and other companies use the same tactics to keep workers from joining unions.

“Part of their strategy was trying to get the community on their side,” Boone says. “They’d go to the ministers and leaders and tell them that we didn’t need a union. ThermalKEM is doing the same thing. They’re coming into a community, they’re trying to get the churches, trying to get the NAACP, any organization they can get to help them.”

Bah, Humbug!

After months of behind-the-scenes persuasion, ThermalKEM decided to announce its plans last Christmas Eve. Residents were stunned by the Scrooge-like timing. “A lot of people were upset,” recalls Brenda Remmes. “We felt that it was very purposely kept hush-hush-hush until the Christmas holidays when people were occupied with other things.”

If the timing was intended to undercut opposition, however, it didn’t work. Four days later, 500 citizens met at a local school and formed Northampton Citizens Against Pollution (N-CAP). The group held marches, sponsored speakers, and quickly collected signatures from 3,701 residents opposing the incinerator—half the number that voted in the last election.

But company machinations proved more powerful than public opposition. When the county commission met on February 4, no vote was scheduled on the incinerator, and two commissioners were out sick. Suddenly, commissioners Vernon Kee and John Henry Liverman announced that they wanted to vote on whether to invite ThermalKEM to burn waste in the county. Commissioner Henry Moncure objected, and stormed out of the meeting in protest when he was overruled.

Having established a quorum at the start of the meeting, Kee and Liverman proceeded to vote in favor of the incinerator. They also recorded Moncure’s vote as “yes,” making the official tally 3 to 0 in favor of the incinerator.

At a later meeting, with incinerator opponent Jane McCaleb replacing a commissioner who had died, the vote went 3 to 2 against ThermalKEM. The battle then shifted to the town of Woodland, where members of the town board voted to annex land for the incinerator and give the company permission to start the permitting process.

Fear and Mistrust

N-CAP maintains its headquarters in a storefront office at the one-and-only traffic light in the town of Gaston. Norma Bryan, a retired beautician, sits by the window, counting the 18-wheelers that pass and answering questions about the group over the phone. Though she has lived in Northampton County for 12 years, Bryan holds on to the fighting ways she learned in New York City. “I’ll fight anybody if I thought it was wrong.”

But the dynamics in the South are different, she says. Despite widespread opposition to the incinerator, few black residents attend N-CAP meetings. When the group sponsored a lecture by Dr. Paul Connett, an incineration expert, several hundred residents turned out—but few were black. Bryan says some of her fellow black residents are afraid to speak out against the incinerator because they could lose their jobs. “If John Doe is working for that little grocery store under Mrs. Someone, he can’t speak too loud because he’s afraid Someone will make him leave.”

Other black residents say they simply feel uncomfortable going to meetings with white neighbors with whom they share little or no history of friendship or trust. Centuries of segregation have taken their toll, says NAACP president Bennett Taylor. “There’s not too much effort of us coming together.”

Yet the reluctance of many blacks to publicly oppose the incinerator doesn’t mean they favor it. Despite the efforts by ThermalKEM to win over black leaders, many black residents say they oppose the incinerator. They may not go to meetings, but their commonsense tells them that the facility will harm their health.

A 35-year-old black woman who grew up in Woodland and works in a convenience store remains unswayed by the promise of jobs at the incinerator. “If you got a job and then you’re going to die right behind it, who’s going to take care of your children?”

Clean-Up Time

Despite the obstacles, black and white residents are gradually realizing that a united front is their only hope of fending off ThermalKEM. Slowly but surely they have come together to fight the incinerator, building trust across racial lines and forging an interracial coalition that many hope will outlast the incinerator controversy. “ThermalKEM as an issue has brought us together as a people,” says NAACP president Bennett Taylor.

Ironically, one sign of the growing unity is black support for Dr. JaneMcCaleb, a white incinerator opponent selected to replace a black county commissioner who died. Even though her appointment diluted black representation on the commission, many view McCaleb as a symbol of a new political climate that questions old ways of doing business.

“It’s an old-style of doing things that’ll have to change,” says McCaleb. “It’ll be very painful. In a way it may be worth it if it forces us to face some of the real political problems we have.”

As director of a five-clinic rural health group, McCaleb knows there are “significant health risks” connected with the incinerator. “My experience with occupational health around here is that the economic incentive of the employer outweighs the occupational health issues,” she says. “There’s the issue of the throwaway worker. Once they wear out, you just go on to the next worker. I think that’ll be what happens in this industry.”

As the controversy drags on, it has become clear to most residents that the real issue being debated is the future of economic development in Northampton County. Can a poor, black, rural county attract clean industries and good jobs? Or does it have to settle for work connected to words like “hazardous” and “waste”?

Those who support the incinerator say it represents the county’s only hope of attracting jobs. “It may not be an IBM, but we don’t have the educational base to attract that kind of industry,” says Commissioner Vernon Kee. “You can’t take people who worked out on farms and put them in front of computers—you need to train them.”

But Jane McCaleb and others opposed to the incinerator believe that there are clean alternatives—and that improving schools and training workers provide the keys. “When the schools improve, the people will receive a better education and look better to other companies,” says Audrey Garner, a black health administrator. “But it’s not going to happen overnight.”

Willie Gilchrist, principal of Northampton High School, wishes the commissioners would put aside the incinerator and focus on increasing the school budget. “I have not seen a lot we have done for children as far as dollars and cents,” he says.

Gilchrist and others concede that education and job training won’t provide a quick fix, but will gradually promote change that is lasting, meaningful — and safe. Already, they point out, the incinerator battle has prompted many residents to reconsider the needs of their county and question the powers that be. Whatever happens to the incinerator, they say, Northampton County will never be the same.

“I think never again in Northampton County will elected officials feel that they can do anything and not be challenged,” says Audrey Gamer. “I think they thought they wouldn’t meet this opposition. They were surprised. Yes, we have a high rate of illiteracy — but that doesn’t mean we don’t have understanding.”

Tags

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)