This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 3, "Fishy Business." Find more from that issue here.

Kannapolis, N.C.—C.W. McKinney’s mouth is open, broken teeth exaggerating a look of wonder, as the retired textile worker listens to an explanation of junk bonds. How the high-risk, high-yield investments became fashionable during the 1980s, financing everything from casinos to takeovers of multibillion-dollar corporations.

How Bel Air financier David Murdock, a friend of Ronald Reagan’s worth an estimated $1.35 billion, bought McKinney’s employer, Cannon Mills, and raided the $102 million pension pool. How he used at least $37 million of it to take over another company, then invested the rest in a California insurance company called Executive Life. How Executive Life bought too many junk bonds, forcing regulators to seize the company in April in the largest insurance failure in U.S. history.

And how this chain of events means that McKinney’s monthly pension check of $36.81 will be cut by 30 percent.

He blinks hard, rocks back in his porch chair, and bounces the rubber-tipped end of his crutch on his right leg, which is permanently contorted in a ballerina’s pirouette. It was shattered across the street in the mammoth brick mill where he worked for 43 years in the bleaching room.

Junk bonds. McKinney, 80, doesn’t get it. “I don’t got an education, but it sounds like there ought to be a law again’t them.”

The educated and the elected are rapidly coming to a similar conclusion. Since Executive Life collapsed under the weight of its high-risk deals, Congress and state lawmakers are realizing that the insurance industry is on the brink of a major disaster. First Capital, an insurance company with subsidiaries in Virginia and California, went under in May, and two months later the state of New Jersey took control of Mutual Benefit Life Insurance Co.

In addition, industry analysts are now acknowledging that policyholders and taxpayers aren’t the only ones who will pay for the collapse of major insurance companies. The looming crisis also threatens the pensions of millions of retirees like C.W. McKinney, as well as hundreds of cities and states that relied on insurance firms to guarantee bonds they issued to build housing.

According to the General Accounting Office, the trouble can be traced to the hostile takeovers of the 1980s. When corporate raiders like David Murdock took over companies, they frequently terminated employee pension plans to help pay their debts. In nearly 200 leveraged buyouts studied by the GAO, the new owners pocketed $581 million in pension money. Overall, federal figures show, employers milked pension plans of $22 billion from 1984 to 1990.

As a result, an estimated four million retirees and their families currently depend on private insurance firms for their pension payments. Executive Life alone swallowed more than $1 billion in pension funds covering more than 80,000 employees, from fast-food workers at Kentucky Fried Chicken franchises to nurses and orderlies at the Southern Baptist Hospital in New Orleans. Tens of thousands of retired workers throughout the South have already seen their pensions slashed.

Blaine Briggs got hurt twice. A retired district manager with Ryder/PIE Nationwide trucking of Jacksonville, Florida, Briggs lost his pension when Executive Life collapsed. He had also followed his employer’s example by investing his life savings with the failed insurance firm.

“We’re going to lose our home,” Briggs told The Charlotte Observer. “You feel like you want to hit someone, but there’s no one to hit.”

Pensioners at Cannon Mills in Kannapolis are just as angry at David Murdock for raiding their pension fund. “It was my money,” says Henderson Gantt, who retired from the mill after 48 years. “I worked for it. He ripped the people off.”

Who Pays?

No one needs to tell nearly 13,000 retired men and women in Kannapolis, a classic Southern mill town near Charlotte, how tough things will become if more insurance companies go under. They are perhaps the most concentrated group of Executive Life casualties, and the most tragic illustration of how Wall Street yanked the net from underneath a financial tightwire that no one in Kannapolis wanted to walk.

C.W. McKinney and other Cannon Mills retirees on a fixed income have dipped into their Social Security checks to pay utility bills or bring home a sack of groceries. Their pensions may not have been much — most were less than $100 a month—but the retirees need the money and consider it a just reward for a lifetime among the looms.

Instead, like Michael Milken, the jailed financier who hooked First Executive on junk bonds, the textile retirees have paid the price for the financial excesses of the ‘80s. But unlike Milken, the pensioners never shared in the spoils of the late gilded age.

Even in the midst of the insurance crisis, the retired millworkers’ needs have not been addressed as much as their endorsement sought. The Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU) made them a centerpiece in a union drive. North Carolina Senator Terry Sanford conducted hearings as a forum to inject a good-guy image into his troubled re-election campaign. Even David Murdock, the man who plundered their pension, posed before television cameras with Senator Sanford in August to announce that he had written personal checks totaling $800,000 to retirees. The gesture, intended to make up for the 30 percent cuts suffered from April to September, was accompanied by an anguished statement.

“I’ve been particularly concerned, myself, with what is morally right, ethically right, and legally right,” Murdock said. “I certainly hope that this payment will mitigate the suffering that people are having.”

Days after Murdock’s pledge, however, the North Carolina Insurance Guaranty Association made it clear that it expects to reimburse Cannon’s former owner the $800,000. The association, run by the industry and funded by dues from insurance companies, was created by state law to protect retirees and policyholders when their companies go broke. (See sidebar.)

“I think Murdock is to be applauded for stepping forward,” said William Patterson, attorney for the association, “but I don’t think he expects the money to be permanently out of pocket.”

North Carolina officials have insisted all along that the insurance association will guarantee Cannon pensions no matter what the fate of Executive Life. Terry Wade, chief financial analyst with the state Insurance Department, says he hopes retirees will be reimbursed in “a matter of months, not years.” In any case, he says, Murdock is not liable for the shortfall, nor is the mill’s current owner, Fieldcrest Cannon Inc.

The bailout is certain to be costly. A French investment group bidding to buy Executive Life would give policyholders 81 cents of every dollar they invested. If the guaranty association makes up the difference, it would have to charge insurers in the state enough to cover $1 billion in policies—the largest assessment ever collected in state history.

So who, ultimately, will pay?

“Whatever costs are incurred by the insurance industry are passed along to the public,” Wade says. “That’s the stark reality.”

A Tale of Two Men

The Cannon pension trouble is about more than junk bonds and a nation’s decade-after fiscal hangover. It also shows how the textile business, the first major industry in the South and still the largest manufacturing employer in the region, has changed. It comes down to the story of two types of men.

Charlie Cannon, son of mill founder James W. Cannon, was the model of the benevolent, paternalistic textile magnate. As head of the operation from 1921 until his death in 1971, he didn’t exactly offer the American dream. But he did offer thousands of relatively uneducated Southerners a roof over their heads, a steady, if minimal, paycheck, and a little compassion. He asked for hard work and anti-union work in return.

Murdock came to Kannapolis in 1982, paying more than $400 million for the mill, the downtown business district, all of the company-built housing, and the 1,073 acres of prime real estate near Interstate 85. He was the model of the ‘80s takeover artist, slashing the workforce by 700, cutting wages up to 30 percent, updating production methods, and forcing mandatory retirements. On one day— “Black Friday” employees called it—some mill hands were given an hour to leave the premises.

In 1986 Murdock sold Cannon’s bath and bedding operations to Fieldcrest Mills of Massachusetts for $250 million. But first he dissolved Cannon’s pension fund, saying it had more than enough money to meet its obligations. He pocketed $37 million and reinvested the rest in annuities with Executive Life.

Lynne Scott Safrit, president of the Murdock development company in Kannapolis, defended the move. Executive Life, she said, was a highly rated insurance company at the time, and “was chosen after careful consideration.”

But Cannon’s old archenemy, ACTWU, challenged the pension switch, charging that Murdock used the money to help fund his 1985 takeover of Castle & Cooke, the San Francisco parent company of Dole Food. “He used the pension fund as if it was another source of money,” says S. Bruce Raynor, the union’s Southern director. “He benefited by investing the money. We consider that ill-gotten gains.”

The union sued in federal court in California and lost. On appeal, the case was sent back to federal court for rehearing. In 1989, Murdock settled with the union out of court for a reported $ 1 million. Raynor says the money will go towards building a new retirement home in Kannapolis.

In the meantime, Executive Life collapsed under its heavy reliance on the junk-bond market. California regulators say the firm invested more than 60 percent of its assets in junk bonds, compared with six percent for most insurance companies. The result: threatened losses for tens of thousands of retirees whose pensions were invested with Executive Life.

“It really is an ‘insult to injury’ story in the textile community” says Jacquelyn Hall, a University of North Carolina historian who has studied the textile industry. “The little bit of improvement textile workers won over the years gets whittled away.”

The Town Paternalism Built

There is little in Kannapolis to suggest that it would be a lucrative trophy for a West Coast financier like David Murdock. The city of 45,000 is dominated by the red brick Cannon Mill, which engulfs 90 acres with smokestacks, water towers, and steel superstructures like an oversized Erector Set.

Next door are four blocks of red brick outlet stores, a tiny reflection of the mill. Neat cottages, sided in aluminum of marigold, royal blue, ivory, and apricot, spread out in all directions.

These are the houses, more than 1,600 of them, that James Cannon started building in 1906 in pine and farm land 25 miles north of Charlotte.

“Mr. Charlie,” as his son was known, took over when he was 21 and made Cannon Mills a giant, employing over 25,000 in the making of towels and bedding.

C.W. McKinney remembers Mr. Charlie with a bowler cocked on his head, making sure that paint was going on all the houses that rented for $25 to $40 a month, right up until Murdock bought the mill. No charge for water. Electricity was a nominal fee. Cannon schools and Cannon hospitals built on Cannon land with Cannon money.

Even Mr. Charlie’s old two-story house, which his wife named For Pity’s Sake, was occasionally thrown open to the help. “We’d be invited up there ingroups to ride the horses and just socialize,” says LaTrelle Smith, 70, who for 45 years raced to put labels on towels.

Murdock, on the other hand, built a luxury lodge to entertain Cannon customers, sandblasted buildings downtown to restore the original red-brick facades, and turned Main Street’s traditional retail shops into factory outlet stores. He also built a loop road—after much heated political maneuvering—to bypass the central business district which he called “Cannon Village.”

The link between company and town was completely severed in 1984 when Kannapolis, long thought to be the nation’s largest unincorporated town, voted to incorporate.

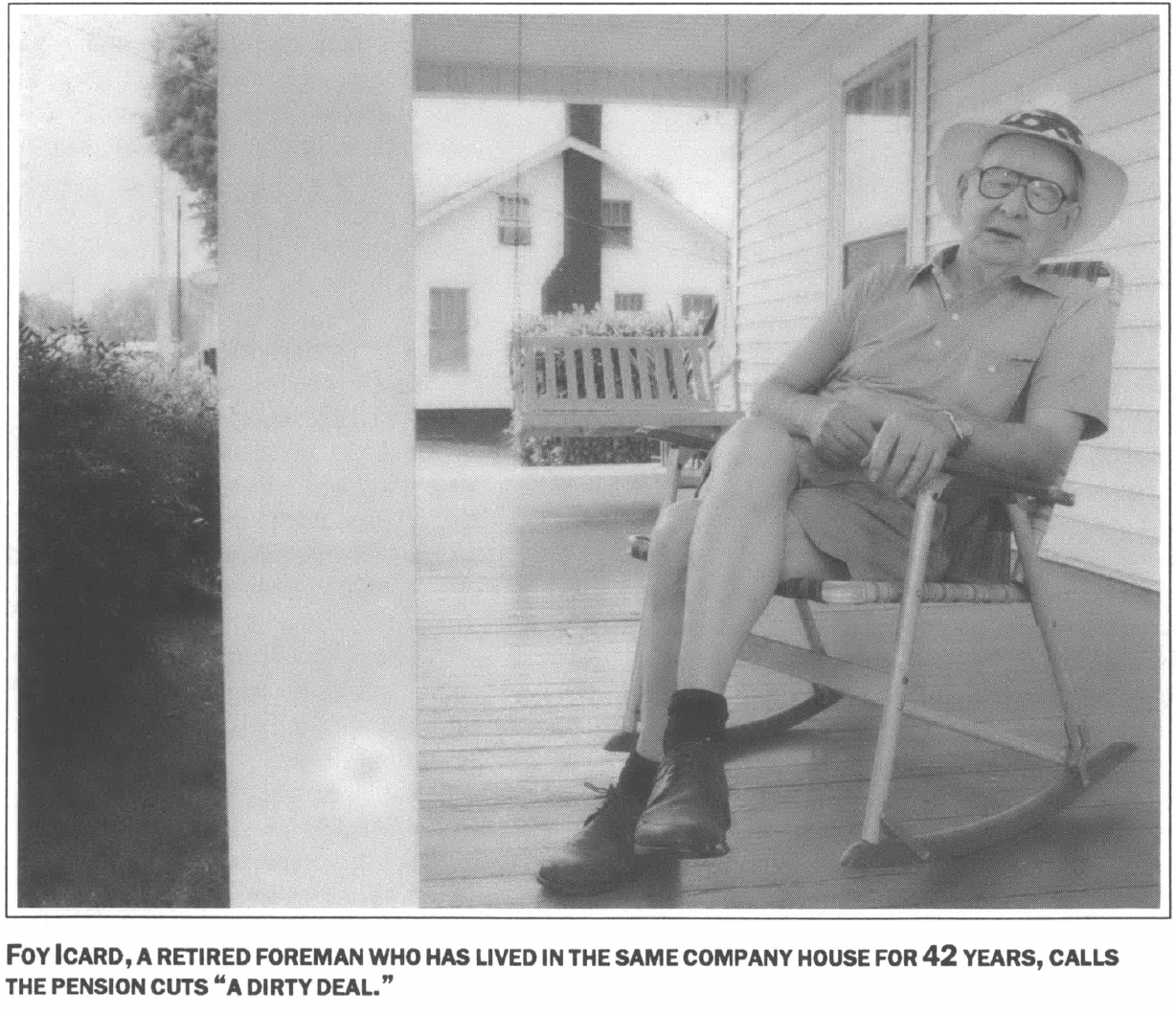

“We had a notion things would never be the same,” says Foy Icard, 80, a retired foreman, or “boss man” as his neighbor McKinney calls him. “Murdock wasn’t a textile man, and he up and bought the whole darn town.”

Icard is quick to admit that he only has a seventh-grade education and that his knowledge of high finance comes from reading the newspaper. But after 42 years of living in the same company house, making the same short walk across the street to work, he didn’t need a degree to see how Murdock was changing Cannon.

The silver-haired Californian hired high-priced consultants and replaced Cannon old timers with managers from the company’s competitors. Instead of trusted “boss men,” engineers with stopwatches judged who worked the slasher machines and looms the best. The old no longer retired when they wanted, the injured or sick no longer worked when they felt up to it. There would be no more C.W. McKinney’s hobbling around the bleaching room.

Icard takes his wide brimmed hat off and points at his neighbor’s house where C.W. sits in the tiny living room watching TV. Icard says he worries about “that old boy” and his reduced pension. “He’s got pains in his legs and has trouble getting around.”

“I can live without the money,” says Icard, whose pension has gone from $104.80 a month to $71. “But I’m lucky. I think it’s a dirty deal that a man works his whole life, counting on a little something when he’s through, and somebody who don’t need it takes it from you.”

“All We Ever Knew”

The tale of the two men who molded Kannapolis is perhaps most vividly illustrated at the town’s YMCA. Everyone here knows that the Cannon Foundation spent millions of dollars on schools, hospitals, and recreational facilities.

But David Murdock? Here between the Charles A. Cannon Memorial YMCA and the Charles A. Cannon Memorial Library, sits the David H. Murdock Senior Center. He donated the land, paid for the bulk of the $5.25 million complex, and continues to support it. He donated $25,000 about the time Executive Life was going under.

The senior center is where LaTrelle Smith spends her ample free time painting, basket weaving, and dancing. As couples of her generation spin to “Sixty-Minute Man,” she tries to put into perspective her 70 years in a company town.

Her mother and father worked at the mill, and she was eager to join them when she graduated high school. “Cannon Mills is all we ever knew,” she says. “We were grateful and loyal. But I never knew I could do something else until my older years. And then it was too late.”

Now she finds her monthly pension of $57.36 cut to $39. “I miss it and I resent it,” she says. “It wouldn’t have happened if Mr. Cannon was still here.”

But while some retired millworkers dream fondly of a return to the paternalistic past, those days appear to be gone forever. Cannon Mills has pushed most of its older, loyal employees like LaTrelle Smith into mandatory retirement—and many younger workers say they don’t give a damn what Mr. Charlie would do.

After the pension fund fiasco, mill workers launched a fast and furious drive to join the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union. Cannon employees had voted down the union twice, the second time in 1985. But this time, many workers were fed up with having their paychecks and pensions at the mercy of Wall Street raiders like David Murdock.

Initial figures from the August election show the union came up 199 votes short. But 538 of the ballots have been challenged, which could result in a union victory or another election.

Whatever the outcome, union supporters say the narrow margin was a message. “We did in less than two months what it took us 15 months to do in 1985,” says Pete McIntyre, a mill worker who was on the forefront of the union drive. “The reason? We have been treated like animals before, but now times have changed enough to give us a way out.”

Sidebar

What’s the Guaranty

By Marty Leary

Marty Leary is research director of the Southern Finance Project, sponsored by the Institute for Southern Studies.

Pensioners aren’t the only victims of the insurance industry blowout. Taxpayers and consumers are also paying the price. That’s because current state laws allow the industry to pass the costs of insurer insolvencies along to the public in the form of higher taxes and insurance premiums. (See "Heading for a Crash,” SE Vol. XVIII No. 1).

Almost all of the states have guaranty funds that are supposed to stand behind consumers when an insurance company fails. The funds were established by state laws, but their boards are controlled by the largest insurance companies in each state.

In spite of their names, the funds offer no guaranty to many policyholders. Some of the funds, for instance, do not protect pensioners. Others prohibit payouts to municipal agencies that invested in insurance products.

Not only is there no guaranty with a guaranty fund, there are no funds, either. Money to pay off policyholders is collected after a failed insurance company is liquidated. Only then do guaranty funds in each state collect assessments from insurance companies selling similar policies.

What’s more, each fund has a legal limit to how much it can collect in a year. According to a study by the non-profit Southern Finance Project, failures as large as Executive Life could exhaust the funds, saddling policyholders with costly delays.

Municipal and state governments will also feel the effects of large insurance failures. In 37 states, insurers are allowed to deduct every dollar they pay into a guaranty fund from their state taxes. As the costs of insurance failures mount, many states will see millions of dollars drained from their budgets.

Many cities and states also relied on insurance companies to guarantee bonds issued to pay for housing and other developments. The Mutual Benefit Life Insurance Co. was backing more than $800 million in bonds when it was seized by New Jersey regulators in July— including $555 million tied up in development projects in Florida, Texas, Tennessee, and Georgia. If big insurance failures hurt municipal bond ratings, they may make it harder for local governments to raise money for housing and other public works.

Sold Out

What can be done to protect the public from paying the price for big insurance failures? With five large insurance companies currently under state control, there is a growing recognition in Washington that the current state-by-state system of insurance regulation may be part of the problem.

One reason the state guaranty funds might not be up to the task of safeguarding policyholders is that they were designed to ward off federal regulation, not to protect the public. The industry itself created the funds in the late 1960s after an unsuccessful attempt in Congress to create a national guaranty fund similar to the one that protects depositors in the nation’s banks and savings and loans. Senator Howard Metzenbaum of Ohio has resurrected the idea of a national guaranty fund to protect insurance consumers. The fund would collect money on a regular basis — not just when a company fails — and would be paid for by the industry rather than taxpayers or policyholders. Metzenbaum blames states for failing to regulate insurance companies, but he also holds President Bush accountable for the current crisis. "Not only did the administration permit employers to steal workers’ retirement benefits, it failed to monitor the benefits that remained,” the Senator says. “As a consequence, the workers and retirees’ benefits were sold out from under them.”

Tags

Joe Drape

Joe Drape is a reporter with the Atlanta Constitution. (1991)