"Something As One"

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 3, "Fishy Business." Find more from that issue here.

Sarah White lives with her two children in a three-room apartment not far from where the Southern crosses the Dog—the intersection of the old Southern and Yazoo Mississippi Valley railroad lines. For generations the spot has been part of the folklore of the Delta, remembered in song and story as a turning point, a place where a decision must be made, a direction chosen. For many black Mississippians, it has represented a way out of poverty and prejudice, a way north to Chicago.

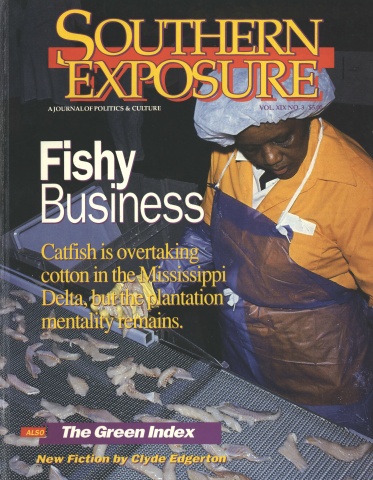

Sarah White chose a different direction. Like most of her friends and family, she grew up working in the cottonfields for $6 a day. She went to college and studied to be a teacher, but wound up pregnant and on welfare. Determined to do better, she got a job skinning catfish at the Delta Pride processing plant.

The work was dangerous and the pay was low, but White didn’t leave town or head north. Instead, she decided to stay and fight for a safe workplace and decent wages. Working “seven days a week from sunup to sundown,” she and a few friends convinced their fellow workers to organize a union at Delta Pride.

As she talks about her experiences, White leans forward on her living room sofa. A coffee table overflows with photos of her family. On one wall hangs a simple plaque inscribed with the Ten Commandments; on another is a diploma from Delta State Community College bearing the credo, “Live for Service.”

When she is not at work, White spends much of her time attending meetings, talking to people, organizing. In her few spare moments, she likes to read Harlequin Romances and watch Arnold Schwarzenneger movies. “Hike him,” she laughs. “He’s strong, and he always gets what he goes after.”

Although White has traveled all over the South in the past year educating people about working conditions in the catfish industry, she still describes herself as “just a little country gal.” The union offered her a job in Atlanta, but she turned it down. “That would have been a chance for real advancement,” she admits, looking around her tiny apartment. “But this is my home. This is where I want to be.”

I started at Delta Pride in 1983. They put me on the kill line skinning fish. I was only there a few weeks before I got to experience how the company mistreats you—hollering and yelling for you to do this and do that.

I was only supposed to skin 12 fish a minute, but they would whoop and holler at you to do as many as you could. I would do 40 a minute—that’s the speed they wanted us at. If you only did16 or 17 a minute, they would call you in and write you up.

We used to have to stand in ankle-deep water all day, for nine or ten hours a day. The debris from the fish — guts, water, skin—would fly in your face. They wouldn’t let you wash it off, so you had to stand covered in guts for hours.

A lot of people would have skin rashes. Our hands used to ache and hurt, but we didn’t know what it was. We knew it was from the job, but at that time we didn’t know it was carpal tunnel syndrome. We didn’t know its name.

The supervisor would harass us. We would ask to go to the bathroom, and they would make us wait for an hour. Then they would come inside the bathroom and holler at us that our time was up. If they didn’t like your attitude, they would just fire you. You couldn’t voice your opinion in no kind of way. It was, “Do what we say do.” There was no other way.

One day my baby was sick. I went to my supervisor and said, “Miss Hines, my baby’s sick. I need to take her to the doctor.” She said, “If you got to go to the doctor, we don’t need you.”

A lot of reporters come in and ask why people put up with that kind of abuse. I guess it’s just Mississippi — that’s what our grandparents did and our parents did. It just grew up in people that you do what you’re told. If you want to work, you do what the man say do. We were unaware of the route you could take to change things. Once we found out that we do have rights, that we can take steps to make our lives better, we took it.

What got me was seeing them firing my co-workers, people I had worked around and had feelings for as friends. I was so angry, I just got filled up. I wanted to do something that would put them in their place. I wanted to say, “We’re human beings and you can’t treat us like this. We got feelings just like you.”

I worked on the same machine as another girl, Mary Young, and we used to talk about how we didn’t have any voice in the plant. We didn’t know a hell of a lot about unions, but in 1986 Mary got an authorization card from the United Food and Commercial Workers. She said, “Sarah, we need some kind of help because of the abuse.”

Mary sent that card in to the union, and three weeks later a representative from the international come down and tell us what we need to do to organize. That’s really how we got started off.

It was four of us trying to organize 1,200 people in the plant. We had to sign up 30 percent of the people on cards saying they wanted to organize a union. We would talk to people during breaks in the bathroom, at the Piggly Wiggly, the WalMart—we worked seven days a week from sunup to sundown, trying to organize.

People were afraid. You just didn’t talk about unions in Mississippi. You go to talking about a union here, you’re looking at losing your job. Once we started to organize, the company got wind of it and started making examples. They fired 16 of us for trying to organize, but the labor board made them give us our jobs back.

The company did more besides firing us. One day they brought $180,000 in cash into the plant in an armored truck. They stacked all of this money on a table, with all these guards around it. They said, “This is the money you’re going to put out in union dues if you join the union. All the union wants is your money.”

Well, it didn’t fool me no kind of way. I knew it was just a tactic to keep the people from organizing. I believe that in any kind of organization you’re going to pay some type of dues. The catfish farmers do it—they put money into their organization. They don’t call it a union, but it’s a group of fish farmers united to make decisions to help themselves. That’s all a union is—a group of workers united to make decisions together.

The company brought in the brother of Medgar Evers. He said, “The union isn’t good for you, the company is going to treat you right. It’s best to keep this plant as a family—don’t bring no outside people in.”

Once we decided to organize, the company suddenly gave us all this good stuff— they threw barbecues, gave away money, gave away fish. We told people, “Go ahead, drink their beer, eat their barbecue. But on October 10, vote yes for the union.”

People were afraid, but we kept on and tried to instill it in them that the union would be better than being harassed and not having any kind of voice. The company had treated everybody so bad, they felt it was the only way out. They thought, “Maybe if we organize, somebody can help me with my aching arm.” When the vote came on October 10, it was 489 to 349 for the union.

After we got organized, we got our first contract. It gave us two extra holidays, a pay raise, a pension plan, a grievance and arbitration procedure. It gave us a voice to say what we want.

But things didn’t change. The company said, “Ain’t nobody going to come in and tell us how to run our business. You all wanted to organize, so we’re going to make you pay.’ They kept on harassing us, trying to get away with a lot of stuff. They just disregarded that there was a union.

When we had a grievance, they would refuse to talk about it. They made us take cases all the way to arbitration, just because they could. We took 27 cases to arbitration, and we only lost two.

When it came time to renew our contract last year, I served on the negotiating committee. The company only offered us a six- cent raise and said we could only go to the bathroom during lunch hour. People thought it was ridiculous. People said, “They think we’re crazy. We’re just not going to accept this.”

We gave them until midnight on September 13 to bring us something better, or we would go on strike. But they wouldn’t do it—they really thought people would accept it and come back to work. So we went on strike.

I was scared. I wanted to believe that my people knew the company was just messing with us, that we couldn’t progress with what they was offering us. I wanted to believe that I had their total support, but something had me afraid. So I told myself, “Regardless of what the results be, I’m going to be out on that picket line if I’m the only one out there.”

At midnight on September 13, I went out there with my picket sign, and there was 100 people there. When the shift started at eight o’clock that morning, cars went to pulling over everywhere, all the way from the plant back down to Highway 49. Everyone came out of the plant. All the workers refused to accept the contract.

You talking about proud, you talking about filled with joy— to see for once that we could stand together and fight this company. I stood at the front of the entrance and people came by and shook my hand and said, “Sarah, I’m not crossing. I’m with you.”

It wasn’t as easy as I thought it was going to be. I thought once we all came out, maybe the company would decide it had to do something. But the company felt they could get other workers. They was losing money, but they were determined to go as long as they could.

The union supplied us with groceries, gave us $60 a week in strike benefits, paid our bills. We had a turkey for Thanksgiving and a nice ham for Christmas. But sometimes we were down and out. We weren’t progressing like we wanted to, but we were willing to sacrifice to make this company do right by us.

I think that support from other states is what really kept us strong throughout those three months on strike. Folks from all over came to walk the picket line with us. It gave the people strength. It picked us up and made us see that this was some-thing we were doing right. It showed us that we didn’t have to take the abuse. It made us feel pride in ourselves.

Finally we decided to launch a nationwide boycott of Delta Pride. We picketed grocery stores, and they took Delta Pride catfish off the shelves. If it hadn’t been for that boycott, I believe we would have been fighting even longer. But when the company started having trouble selling their product, they came back and settled the contract real quick.

That strike changed the people. I’ve been with them from day one, and the attitudes are totally different. People used to be afraid, but now they are loud and lively. They won’t stand for it when the company tries to mistreat them or cheat them out of something. It’s not just me and three more running around trying to sign people up. Now you got people all throughout the plant that will take an application and go to a new worker and say, “Hey, brother, we need you to join this union.”

The morale is stronger now since the strike. We learned that if you do something as one, you most likely succeed.

The farmers couldn’t believe we went on strike—900 black single mothers fighting all this harassment and abuse. You always hear the farmers say, “I don’t see what they’re going on strike for. They was on the welfare line before.” Well, that’s what it’s all about—trying to do better. A lot of single mothers was tired of the welfare line. We wanted more than $120 a month to support our kids. That’s why we went to work, so we could earn our own money and feed our families.

The whites always think of us like we are still in the days of slavery. We chopped cotton. Our parents before us chopped cotton. Our grandmothers worked in their houses. Mississippi has always been based on that plantation mentality, that prejudice. We say it’s time to change. There should be opportunity for all, not based on the color of your skin.

I chopped cotton. I was 12 years old. I used to go to the field with my aunt after school and during the summers. We had to go, because we had to help Momma. We picked cotton and chopped cotton from seven in the morning until six in the evening, with just an hour lunch break. We would make six or seven dollars a day.

My big momma used to tell me stuff about when she was growing up, about how white people used to do when she was working in their houses, how hard times were. I never paid any attention. But when I got older and went to Delta Pride, I understood that plantation mentality she was talking about. I experienced it. I didn’t believe that people had that much prejudice in their hearts, because I had never experienced it.

At Delta Pride, our supervisor would tell us point blank, “You’re too dumb and stupid to do anything but use your hands.” I guess we showed them how dumb and stupid we are. We really have some intelligent people working in the plant, people with college degrees. Sure there are people in there who can’t read, but they have common sense, and common sense is the best sense you can have.

As far as I’m concerned, we had it better out there in the heat of the cotton field than we do in the catfish plant. All they did was put a roof over our head. At least in the field we could go to the bathroom when we needed to. In the plant, the mouth is the whip, the pencil is the whip. At Delta Pride, it was either you do it our way or you hit the gate.

When we started at Delta Pride, that company was in a three- room trailer. We made this company millions and millions of dollars. We missed PTA meetings, we missed graduations, we sacrificed our families for this company. We’re not trying to take over, we’re just trying to be fair. Give us a decent workplace, a decent medical plan, a decent pension plan. We don’t want the whole pie, but what’s wrong with a slice?

When I was growing up, I really wanted to be a nurse. I wanted to advance, to do something to help my people. Since I started working with the union, I’ve met so many people with a mind to help the world. Since I got that feeling in my heart, I don’t think there’s anything I’d rather do than show a brother or sister that things can be better—that their workplace can be changed if they put forth the effort.

My interest is working with the people, showing them that they can make it. My whole goal is to see Delta Pride turn out as a decent workplace, so my daughter can go to work there if she wants to.

I hope that reading about us helps other people decide that they don’t have to take abuse that a company dishes out. If anybody’s in our situation, now’s the time to make a stand.

I am a different person now. I believe in The Dream. I had heard about Dr. King and what he was trying to do for black folks, but that didn’t mean nothing to me. Now, dealing with the union, trying to organize, talking to workers from all over the world, it has taught me a lot. I am stronger than I used to be.

Before, I was Sarah White. I was just another black worker. Now they respect me for who I am. I feel better about myself, because I let that company know what I’m capable of doing. They talk to me like a woman. We live by the Bible—and the Bible is our union contract.

We didn’t bring outsiders in — we are the union. It’s the people. It was our choice to change that plant so it wouldn’t be harmful to us. We speak for ourselves.

When people say “union,” they think it’s people coming in trying to run their business. I don’t think it’s about that. It’s about democracy—the most purest form of democracy you can have. It’s a way to make that company respect you, give you the dignity you deserve, so you can profit from your sweat and hard labor.

We were just hard-working women wanting to advance, wanting to come off the welfare line, wanting to give our babies more than what that welfare check could do. These white farmers wanted to take advantage of us, work us for nothing. We just found a tool to back them off, to make us respect us for who we are—hard-working women who want to advance in life.

Things are better now. We have a long way to go, but I’m not discouraged. You got to crawl before you walk. It’s going to take three or four contracts, but we’re going to see results. I know it’s coming. Because this catfish is not going anywhere—it’s booming, and it’s here to stay.

I’m here to stay, too. The fight is not over. Maybe one day in 10 years you’ll see me again and say, “Well, Sarah, you said you was going to lick ’em, and you did.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.