This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 3, "Fishy Business." Find more from that issue here.

Hollandale, Miss.—They were gathered together on a hot summer Saturday in the Delta: doctors and lawyers, mayors and ministers, university presidents and civil rights activists. All of them were leaders in their communities, and they had all come to talk about what they could do to change the catfish industry.

They had been talking for hours, thinking and strategizing, when Arnett Lewis stood up. Lewis, a large black man with a calm and commanding presence, was founder of the Rural Organizing and Cultural Center, a community group that had been on the forefront of the civil rights movement in Mississippi for years. He began to speak, slowly at first, but with an increasing intensity.

“If we want to impact the catfish industry in all the ways we have discussed today, we must find a way to hold the industry accountable to the community,” he said. “It’s not going to happen just by organizing the plant and the workers; it must extend to the family and the community.

“I recall coming home one night in Alabama years ago at about two thirty in the morning and seeing a lot of folk—mostly black women—walking in the street, going in the same direction. There was a bus parked down at the end of the street, and they were all catching that bus to go pluck chicken in a poultry plant 40 or 50 miles away.

“That experience had a tremendous effect on me, especially when I hear things about how black people don’t want to work, how they’re lazy. Need dictates that a mother get up and leave her children and go to a dehumanizing workplace. Black women in this country are being enslaved, and we must help communities develop effective organizing strategies and educational programs to place a different demand on the catfish industry—a demand that the industry reinvest its profits in families and the community.”

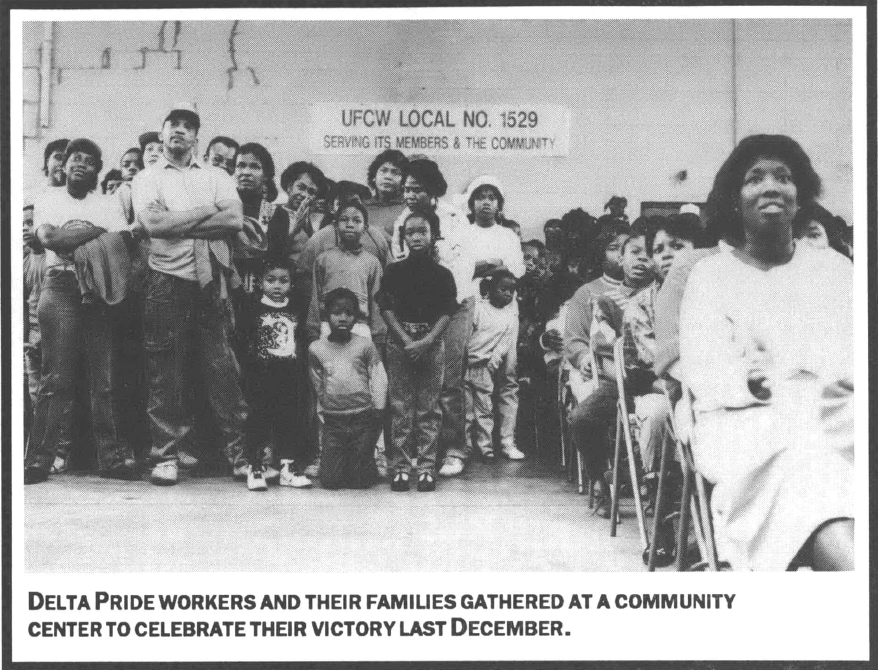

With a few simple words, Lewis captured the essence of that remarkable gathering. Inspired by the example of hundreds of black women who had gone on strike at the Delta Pride catfish processing plant, community leaders had come together to see what they could do to extend the struggle beyond the plant gates.

Afterwards, everyone in the room had the sense that it was the start of something momentous. “This movement is something that was a long time coming,” said Mayor Robert Walker of Vicksburg. “We cannot in good conscience let what happened in the cotton fields happen in the catfish industry.”

L.C. Dorsey, executive director of the Delta Health Center in Mound Bayou, put it even more simply: “I see it as being possibly the second civil rights movement.”

Departing from the Past

The catfish project, as it soon became known, got its start among workers in the processing plants. When women at Delta Pride struck for better wages and working conditions last year, civil rights leaders from across the country traveled to Mississippi to join them on the picket line.

For Isaiah Madison, it was a trip home. The son of a Desoto County sharecropper, Madison was born and raised in the Delta and worked for 25 years as a civil rights activist, public interest lawyer, and Methodist preacher. As a senior attorney with North Mississippi Rural Legal Services in the late ’70s and early ’80s, he represented black farmers being driven from their land at the same time that white planters were beginning to cash in on catfish.

“It was during that time that I was struck by the tremendous economic potential of the catfish industry—and by the painful exploitation of the mostly black female workforce,” Madison says. “I witnessed the systematic restriction of black Mississipians to low-paying jobs, cutting and gutting catfish at great cost to their physical and emotional health.”

When workers at Delta Pride walked off the job, Madison was one of the first to join them on the picket line. As executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies in Durham, North Carolina, he began talking with catfish workers and community activists in Mississippi. It was time, he concluded, to bring together those fighting for reforms in the workplace with those struggling for change in the community.

“It is clear that we need to organize a movement that will build on the resources of the church, grassroots community organizations, black small farmers, the union, and universities,” he says. “The time has come to pull together in a cooperative effort.”

The result was the June gathering in Hollandale, an unprecedented meeting of diverse participants from across the state. Those attending included health professionals from clinics in Tchula and Mound Bayou, labor leaders with Mississippi Action for Community Education and the A. Philip Randolph Institute, the mayors of Hollandale and Vicksburg, and educators from Jackson State, Mississippi Valley State, and Memphis State.

Although each participant came to the session with different perspectives and experiences, all agreed on one thing: the need for a bottom-up, grassroots organizing effort to empower the community.

“This is a very important and historic meeting,” said Dr. Leslie McLemore, director of the Universities Center at Jackson State. “The plantation mentality prevalent in the catfish industry has been a part of our state for a long time. However, there is a sense in which this gathering is a departure from the past. The project we’re discussing is a judicious combination of planning and organizing—basing our actions upon sound and systematic research.”

Greed and Need

In essence, participants say, the strategy of the project is twofold: to fight to improve wages and working conditions inside catfish plants, and to push for true economic development that benefits the entire community.

“We seek to combine social change strategies of economic justice and economic development,” says Madison, the interim coordinator of the project. “We want to effect needed changes in the catfish industry, but we must also develop and strengthen the internal resources of the workers and their communities.”

The key elements of the project include:

Research. Catfish workers and Mississippi-based researchers will prepare a detailed case study of the role and status of women in the catfish industry, and review their findings with workers, farmers, and grassroots leaders. The results will guide organizing and education strategies. From the start, workers and their families are playing an active role in the project. “Often folk come in to do research and supply a guinea-pig status to the people,” says Leroy Johnson of the Rural Organizing and Cultural Center (ROCC). “We plan to guide researchers, so that the entire community is part of the research process.”

Organizing. Community activists will hold a series of workshops to train local leaders among catfish workers and their families, educate workers about health care and compensation for injuries, develop a “workers manual” on employee rights, and push for federal safety standards for repetitive motion disorders.

“The union is the right way to go to protect workers, but we can’t begin to unionize these plants without serious, organized community support,” says Charlie Horhnof the A. Philip Randolph Institute. “Without community support to apply pressure, these companies will not comply with existing laws. We have to hold the industry accountable to workers.”

Economic Development. The project will also provide education and training to enable minority entrepreneurs to break into the catfish industry and related businesses.

“We can’t depend on the industry —the plantation system — to provide adequate livelihoods for black, poor people in the Delta because it is controlled by people operating out of greed,” says Isaiah Madison. “It leaves no alternative except to build a movement to enable people to do for themselves, to provide an economic livelihood for themselves.”

The bottom line, Madison adds, is that those who do the work must have a fair share in the ownership of the industry. “White farmers are being enriched at the workers’ expense. Plant owners are increasingly large national corporations headquartered outside the state. Money is being sucked out of Mississippi, and even the profits that stay in the state benefit white landowners, not poor blacks.”

Profits and People

Arnett Lewis grows impassioned whenever he talks about the catfish project and its potential for uniting and mobilizing diverse elements of the Delta community. “This is very exciting. For a while now, there has not been a lot of movement activity in Mississippi outside of the political arena. This project offers a very important opportunity for us to organize people around economic issues at the grassroots of the rural South.”

Like other participants in the project, Lewis sees it as a chance to address the roots of poverty and racism. “If we’re going to turn the living conditions in Mississippi around, we have to look at the economics of the state—and the catfish industry has become one of the principal economic resources, generating billions of dollars and providing thousands of jobs.”

Lewis got his start as an organizer in the late 1970s, when he quit his job in the Lexington public schools to lead a black boycott of white businesses. The goal, he says, was to pressure white leaders to put a stop to police brutality against minority youths.

“The demonstrations lasted for almost nine months,” he recalls, “but in the end we changed the racial composition of the police department from 20 percent black to 50 percent black.”

After the boycott, many of those who participated decided they needed an ongoing community organization to address a broad range of social issues. The result was ROCC. Over the past decade, the group has helped bring drinking water to isolated communities, led a campaign to halt the jailing of mentally ill patients, and helped students publish an oral history of African-Americans in Holmes County.

“Organizing is what we do,” says Lewis. “We help communities respond to problems as they perceive them.”

That same philosophy extends to the catfish industry. “It means enabling people to do for themselves,” says Lewis. “We have an abundance of resources that have not been tapped. I think the project offers an opportunity to consolidate some of those resources so they can benefit not only the workers, but the entire community.”

Lewis says the project also represents a chance to extend the vision of the civil rights movement to include economic rights. “I think the catfish industry owes something to the community. Is the industry putting enough of its profits back into the education of the people who create those profits? Is the industry concerned about health care for the citizenry of those communities? Is the industry concerned about other issues like drug abuse and teenage pregnancy, and is it giving money to address those problems? The industry must be held accountable.”

The Art of Work

Before she became head of the Delta Health Center, L.C. Dorsey eked out a meager existence as a sharecropper. She likens the catfish industry to the days when cotton ruled the region.

“It’s very much like the sharecroppers 30 years ago,” she says. “Cotton was king. The owners of the plantations were making a killing, and we weren’t making anything.”

Dorsey says the legacies of slavery and sharecropping have crippled the Delta just as surely as high-speed jobs in catfish processing plants are crippling workers. “The most significant challenge we face is the economic status of the area,” she says. “This is such a poor area. The owner always knows that for every worker who says, ‘I’m not coming back till you do something,’ there are 40 unemployed people waiting to take that job.”

Working in the clinic, Dorsey sees injured catfish workers almost every day, their hands crippled by the rapid, repetitive motion of the processing line. Already, she says, black women who work in the plant are taking part in the organizing project.

“The best direction for us who want to help alleviate the problem must come from the people who feel the pain,” she says. “It is very important that we look at how women who are employed in the industry perceive their work. In our effort to improve the workplace, we need to find a way not to destroy those things that they feel positive about. For example, I’m sure there are women in those plants who can filet fish as an art. We need to be sure that we don’t takeaway how the little boy or girl perceives his or her mama as the person who can filet the most fish without giving them something else to feel good about.”

All of the participants in the project concede that it will take substantial fundraising and years of painstaking organizing to achieve their goals. But it is hard to escape the feeling that everyone involved in the effort shares a tremendous sense of hope—a sense that, this time, the movement won’t be denied.

“This is not just another project,” says Arnett Lewis. “It’s a necessary phase of change in Mississippi. It is a bottom-up strategy that weaves the people who are most affected into the fabric of the process. In the long haul, they are the ones who will change their communities. And if we can change conditions in Mississippi, then we can change the conditions throughout the South and the rest of the country. Once we get rolling, there will be no stopping us.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.