This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 3, "Fishy Business." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Leland, Miss.—Rose Ross sits on the sofa in her living room, her swollen right hand limp in her lap. “I can’t hardly hold too much in my hand,” she says. “I can’t hold no skillet. Sometimes it hurts me to raise my hand to comb my hair. These curlers have been in my hair for four days because it hurts too much to take them out.”

Ross suffers from carpal tunnel syndrome, a painful nerve disorder brought on by years of high-speed, repetitive work on the “kill line” at the Delta Pride catfish processing plant. She worked for the company for six years, ripping and gutting fish as they sped by on a conveyor belt—33 fish a minute, 1,980 fish an hour, as many as 20,000 fish a day.

When her hand started bothering her, a doctor told her she needed to be assigned to less dangerous work. The company told her she was fired.

“They didn’t give me no workers compensation or nothing,” Ross says. “They told me I was terminated because I couldn’t do the job for Delta Pride. Then they walked me to the gate. They just showed me the door and told me to get stepping.”

Ross looks down at her throbbing hand. A short, determined looking woman of 32, she lives in a small blue house on a narrow street with her husband and her blind grandfather. She speaks calmly, but now her anger starts to show.

“It makes me mad,” she says, her voice rising. “They cripple me and just get rid of me. They want all the money for themselves — they don’t want to pay you for your injury. But we’re the ones who make the money for them. They just stand behind us with stopwatches and tell us to work faster. That’s why so many people’s hands are messed up today—because they stood there and made us cut fish so fast so they could get richer. It ain’t right, they cripple you like that and don’t give you nothing but a goodbye.”

Ross is not alone. Hundreds of workers at Delta Pride and other catfish plants in the Mississippi Delta have been injured on the job in recent years. Like Ross, most have been crippled by the fast and furious pace of the assembly line, which forces them to perform the same motions, over and over, thousands of times an hour.

Despite the danger, the industry has devoted most of its energy to downplaying the risks. “We have safety committees in every plant,” says Walter Harrison Jr., communications manager for Delta Pride. “We want people to be happy with what they’re doing.”

But federal records tell a different story. Last year, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration cited Delta Pride for exposing employees to dangerous working conditions—and for knowingly covering up the risks by failing to report injuries on federal OSHA logs. It was only the second such citation in OSHA history. The penalty: a fine of $12,000.

To add insult to injury, most catfish workers put their bodies on the line for low pay and long hours. Most take home less than $10,000 a year in return for working shifts that often stretch to 10 and 12 hours a day. Almost all of the workers are black women, and many are single mothers. Most report being subjected to constant harassment not far removed from the cotton fields.

“Delta Pride is just like in slavery time,” Ross says. “Somebody always standing over you, telling you what to do. To them, we’re just here today and gone tomorrow. What do they care? If you get hurt, that’s just one more black nigger gone and another one coming to get crippled.”

“They Mess You Up”

Driving through the Delta on a summer afternoon, it’s easy to see how farm raised catfish have transformed the agriculture and economy of the region. Large blue ponds punctuate the countryside, shimmering among vast green fields of cotton and soybeans and rice. In all, planters have submerged more than 90,000 acres of Mississippi farmland, and catfish has surpassed cotton as the leading crop in Humphreys and Sunflower counties.

Like cotton, the new harvest has made farmers rich; the catfish industry took in $360 million last year. But unlike cotton, local farmers retain control of much of the catfish business. Delta Pride, which manufactures more than a third of all catfish sold nationwide, is owned by a cooperative of 160 Mississippi farmers, and most of the feed and equipment suppliers are locally owned.

Catfish farmers in the Delta are proud of their success. “We do the processing right here, so we keep most of the money right here in Mississippi,” says Harrison, the Delta Pride spokesman. “The catfish industry has turned out to be vital to the economic development of this region. Why, many of these smaller towns wouldn’t have any reason to exist if it weren’t for catfish.”

But what is less visible than the acres of catfish ponds is the pain and suffering the industry has inflicted on its employees. Mary Robinson worked alongside Rose Ross as a ripper on the Delta Pride kill line, the section of the plant where fish are beheaded, gutted, skinned, and fileted. She still remembers her first day in the plant six years ago.

“I’ll never forget it,” she says. “I was shocked. I had never been in a place like that. I was scared of those big old live catfish. It was a stinking scent there, made my stomach sick. Eventually I just got used to it.”

Robinson lives in a cramped apartment in Leland crowded with framed pictures of her six children. She has a broad smile and an easy laugh. As she moves about the tiny kitchen, putting away the breakfast dishes, her left arm hangs useless at her side.

Like her friend Ross, Robinson began having problems with her hand after a few years on the job. “It just got plumb numb, like pins be sticking in it.” Her doctor diagnosed carpal tunnel syndrome, and cut her hand open last March to try and relieve the pressure on her median nerve. “Nothing they did helped,” Robinson says, pointing to the scar on her palm. “My hand just swelled up and hurt. I ain’t got no work in my arm.”

Then, on June 27, her supervisor called Robinson into the office and fired her. “It makes me mad,” she says. “I did all that work, ripping, ripping, ripping those big fishes with those dull knives from eight in the morning until nine at night. And now I be hurt the rest of my life— the rest of my life.” Robinson’s youngest daughter wanders into the room and climbs on to her lap. “Ain’t nobody else going to want to hire me, with the condition my arm’s in. That’s a fact. I can’t live without a job. I have my house and my kids to take care of. How can I do that on $98 a week unemployment?” Johnny Stuckey was also fired by Delta Pride after he was injured on the job. A muscular 20-year-old, Stuckey started lifting 60-pound tubs of fish on the filet line last June. “It was pure hell, that’s all,” he says. “The supervisors make it hard. They stay up on you, constantly making you work faster.”

Within weeks, Stuckey could barely move his shoulder. “I thought I had pulled a muscle, but the doctor said I needed surgery for tendonitis. It just got numb and tingling. I couldn’t even pull my shirt on.”

But when the surgery didn’t work, the company told Stuckey to turn in his ID badge and leave the plant. “It happens a lot,” Stuckey says, shrugging his shoulders. “I know one boy just got his finger cut off on the head saw.” He shakes his head. “I don’t recommend nobody going out there to work. They mess you up bad.”

Stag Hounds and Fish Heads

The Country Skillet processing plant is located in Isola, just down Highway 49 from Delta Pride. Owned by the poultry giant ConAgra, the factory is a haphazard, low-slung building planted among fields of cotton and soybeans. Inside the lobby, a large framed engraving features imperious redcoats on horseback. The title reads, “The Meeting of Her Majesty’s Stag Hounds on Ascot Heath.” Entering the plant from the rear, as most catfish do, it’s not hard to see why workers get hurt. Here, as at other catfish plants, the emphasis is on speed. Thousands of pounds of fish are brought in live, writhing and flopping in the back of big trucks. The philosophy is simple: The quicker they ’re processed, the fresher they’ll be. Workers at the plant gut, chop, filet, and package more than 150,000 pounds of catfish every day.

In the loading area, the fish are dumped into holding vats, stunned with an electric shock, and carried into the plant on a conveyor belt. There, workers on the kill line take over. Women operating head saws decapitate dozens of fish a minute, slinging the heads into a bloody pile. Rippers slice the beheaded fish in half, and rows of “lung gunners” jam suction tubes into the fish to suck out the guts. The heads and other remains ride a separate conveyor belt to a small rendering plant out back, where they are recycled into catfish feed.

The plant is wet and cold and noisy with the sound of saws and belts and cooling fans. A slight fish odor mingles with the smell of chlorine. Workers wear blue hair nets and white lab coats spattered with blood.

On the kill line, workers race to keep up with four machines known as 184s—long gray monsters that perform the same tasks automatically. Using their hands, nine workers are expected to behead, rip, and gut 60 fish a minute. The same number of workers operating three 184s prepare twice as many fish — and filet them— in the same amount of time.

Like most manufacturers, catfish processors would like to replace their workers with machines. But for now, most simply can’t afford it. “I priced one of the184s one time,” says a supervisor who worked at a small processing plant. “When I saw what it would cost, I just give up.”

After the fish are ripped and gutted, workers skin them, remove the fins and bones, and cut them into filets with yellow-handled knives. “It’s a problem, working all day with a knife,” says a woman on the filet line. “Sometimes we stand back-to-back to keep from falling over from exhaustion.” After the fish are fileted, they are washed, chilled, and transferred to the processing side of the plant. Here, they are prepared according to various tastes — marinated, breaded, barbecued—before being frozen and packed for shipping.

Officials at Country Skillet acknowledge that workers face the risk of repetitive motion disorders. “It’s getting to be pretty widespread,” says Eddie Steele, a former union steward who now works as a personnel manager for the company. “We’re doing stuff to prevent it. I won’t say eliminate it, because I think it will always be a problem.”

Yet Steele and many shop-floor employees say things are better at Country Skillet than at their largest competitor. “Delta Pride treats their employees like they’re machines,” says Steele. “They’re run by farmers, and farmers are more inclined to treat people like machines. They still have that old plantation mentality. They ’re just hard—all that money they’re making, and they still don’t want to look out for their people.”

Flowers and Crutches

John Short lost both his legs to a machine at the Delta Pride plant in Sunflower last February. He was working a Sunday-morning shift when he slipped and fell into an ice grinder. He was stuck in the auger of the machine when an ambulance arrived.

“When they removed him both his legs were still somewhat attached, one by skin,” said Jimmy Blessitt, administrator of South Sunflower County Hospital. “The other had nothing left but bone.” Doctors amputated Short’s right leg below the knee and his left leg above the knee.

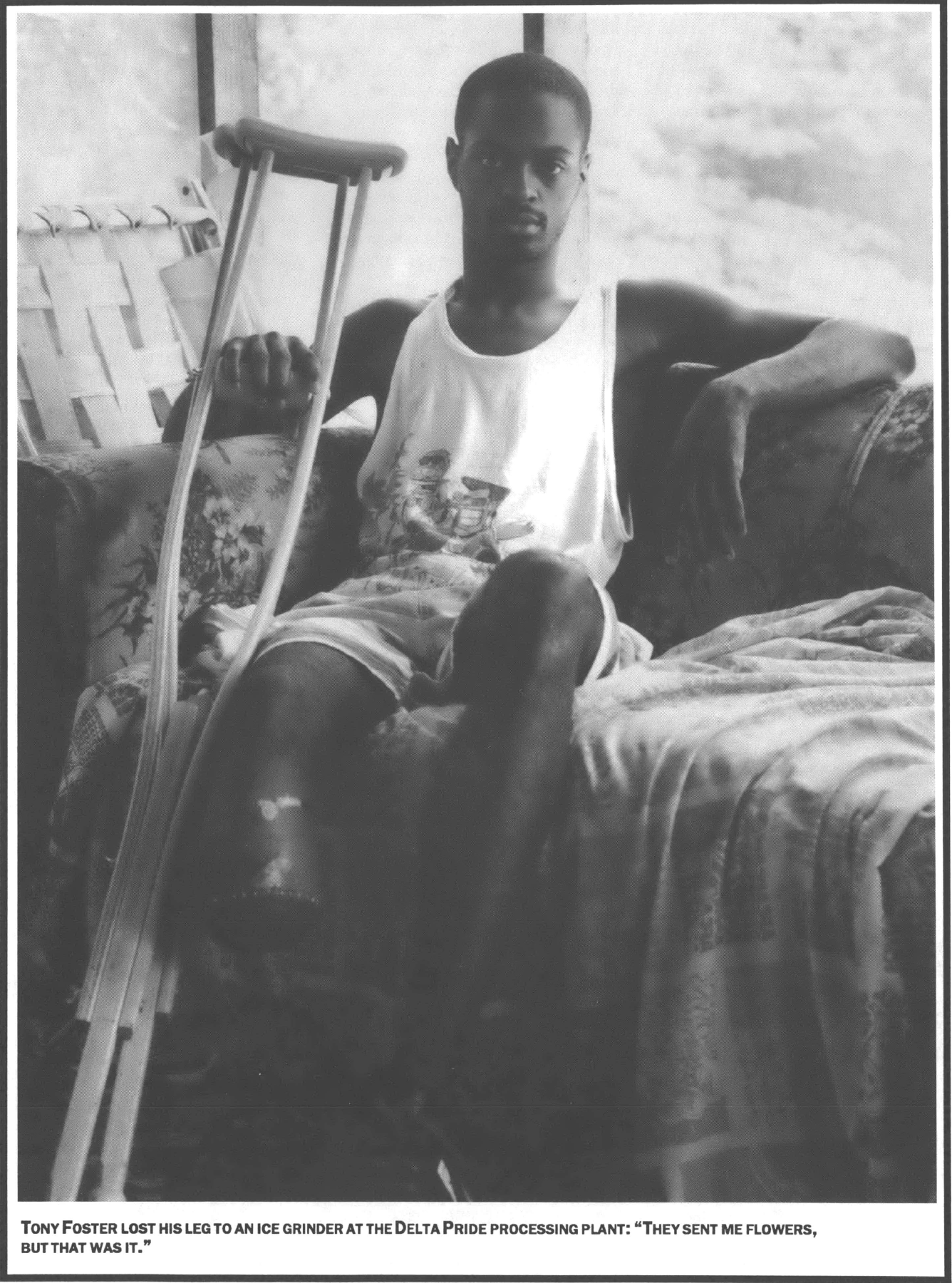

Four months later, Tony Foster was on his regular shift “working the floor” — lifting trays at the main Delta Pride plant in Indianola. “A dude had quit, and my supervisor asked me if I would work in the ice room. I said sure, since it was easier than what I was doing. Working the floor was bad on your back.”

Foster, a wiry 22-year-old, started chipping ice on a conveyor belt. “The floor was wet, and my foot slipped,” he recalls. “The guard around the auger that runs the conveyor belt slipped, and the auger started grinding up my foot.”

Barely two weeks have passed since the accident, and Foster is sitting in the living room of his family’s rickety wooden house in Beulah. His 10 brothers and sisters crowd the tiny room, watching television. Beulah is 40 miles from the Delta Pride plant, but Tony and his relatives would crowd into a van early every morning to make the drive. He attended Mississippi Delta Junior College, but couldn’t find a job. “I used to chop cotton,” he says. “I didn’t want to, but I didn’t have no choice. Wasn’t nothing else ’round here to do, so I just started working at Delta Pride.”

Foster reaches down and peels the bandage off the stump on his right leg where it was amputated below the knee. As he talks he strokes his leg, gently, as if he cannot believe part of him is no longer there. A quiet man, known to his friends as “Dirt,” he wears a t-shirt, shorts, and one black sneaker. He speaks softly, and shrugs a lot, and smiles shyly, both pleased and uncomfortable with so much attention.

“At first I was scared, but since then I’ve been taking it calm and cool.” He shrugs. “I get a new leg fitted next week.”

And the company? “They haven’t even talked to me since it happened,” Foster says. “They sent me flowers, but that was it.”

When Tony leaves the room on crutches to answer the phone, other family members erupt in anger. “As much as Delta Pride is making, and they can’t take better safety precautions,” says his older sister Bearlene. “It should be their number-one priority.”

His brother Marvin shakes his head. “It’s dangerous in there,” he says. “They’re the biggest industry in the city, and they’re making a killing off that cheap labor.”

God and Rose

Rose Turner heads out of Indianola, driving north on Highway 49 toward Memphis. She has put 75,000 miles on her car in the past two years— “all of it on this road,” she laughs.

Turner represents catfish workers who belong to United Food and Commercial Workers Union Local 1529, and she crisscrosses the Delta keeping in touch with the membership. Workers at various plants joined the union in the mid-1980s, and they showed their clout last year when nearly 1,000 of them walked off the job at Delta Pride, touching off the largest strike by black workers in Mississippi history. (See sidebar.)

Today Turner is headed for Pride of the Pond, a small processing plant in Tunica and the first to vote to join the UFCW. “I started out with them from day one,” recalls Turner, settling back for the long drive. “I’m close to these members. The company ain’t going to shit with these crazy-ass people up here. They got unity. They’re going to stick together.”

Turner is a short, slender woman with a brilliant smile, but she has a fierce stare and a mouth that would frighten the most hardened prizefighter. “God can’t intimidate Rose Turner,” says a union supporter who has watched her take on company officials. “A black woman in the Delta dealing with all these white racist motherfuckers — how far do you think she’d get if she let anyone intimidate her?”

Turner seeks to ignite others with her fighting spirit. “I want my members to learn to stand on their own feet. I try to teach them that the union is only as strong as its members. You have to know your contract, and you have to fight for it.” With the support of the union, she points out, catfish workers have won better pay, vacation, and working conditions. “You can’t run from a problem,” she says. “You have to fight it head-on.”

In Tunica, Turner meets with workers from Pride of the Pond at the local senior citizen center. Luella Smith, a member of the union negotiating committee, reports that some women almost passed out that afternoon, working in near 100-degree heat. “It was so hot in there, they had to open the door to the cooler,” she says. “Instead of putting all that money into the flower beds on the front lawn, they should get us some air conditioning.”

Smith remembers the days before the union, days when workers received no vacation and only three holidays—Thanksgiving, Christmas, and the Fourth of July. “It was tough times then,” she recalls. “We never knew what time we would get off. One night we just left at 11 o’clock at night—we couldn’t take no more.”

Smith and others remember skinning and fileting 1,000 pounds of fish a day. “My hand hurts right up through here,” says Sonora Armstrong, pointing to her palm. “It gets so stiff and puffed up, I can’t open it.”

Throughout the week, in meeting after meeting, Turner hears the same stories from workers at different plants. Supervisors who won’t let them go to the bathroom. Hands crippled from overwork. Long, unpredictable hours. Wages too low to support a family.

At a meeting of Delta Pride workers, union members report that the company is making them work a seven-hour shift each weekday, and then ordering them to work on Saturdays to make up the remaining five hours — without paying them overtime.

“We’ve worked ’bout every Saturday for six months,” says Mary Ann Diggs, who packs boxes at Delta Pride. “I’m tired of going in every day and never getting any overtime. I want to see my children on Saturday.”

Corinneiler King, a filet cutter, nods in agreement. “I can’t get a babysitter on Saturday,” she says. “Sometimes I have to leave my children at home alone.”

Jailing the Witness

The company tactics get to Rose Turner. Back in the union office in Indianola, she tells Roger Doolittle, an attorney from Jackson up to handle an arbitration case, about a Delta Pride worker with carpal tunnel syndrome. “They said she couldn’t perform her job duties and told her to file for unemployment.”

Doolittle looks startled. “Not workers comp? Unemployment?”

“Yes!” Turner shouts. “People get hurt, they just fire them. We need to get rid of these motherfucking no-good sons of bitches!”

Doolittle leans back and puts his feet up on a desk. “I don’t think this company had much respect for this union before the strike,” he muses, stroking his beard. “There are still problems with health and safety, but it’s improving.”

“Shit! ’Turner interrupts. “I’m tired of these assholes!”

Doolittle is quiet, thinking. As part of the settlement of the OSHA citation, he says, Delta Pride has agreed to implement an ergonomics plan to slow down the kill line, rotate workers in hazardous jobs, improve equipment, and provide better treatment to injured workers. “I look to organized labor in Mississippi to be the leaders in workplace safety. I don’t think the companies are going to come forward on their own. I think this union has accepted the challenge to provide more than just money and holidays —they are fighting to provide a safe workplace.”

For the most part, Delta Pride has fought efforts to improve working conditions every step of the way. Before the strike, the company refused to negotiate employee grievances, insisting that every complaint go before an arbitrator—a costly and time-consuming procedure. Of the dozen cases that have gone to arbitration, the company has lost all but one.

The morning of July 10, Turner and Doolittle sat across a table from company attorneys at an arbitration hearing in the Quality Inn in Indianola. The union wanted to reopen the case of Louis Cain, a Delta Pride worker fired in 1988 after he allegedly threatened supervisor Jerry Hynes with a pipe. Fred Boatman, a worker who had testified against Cain, was now coming forward, saying the supervisor had bribed him to lie about the pipe incident.

On the witness stand, Boatman said he had been fired from Delta Pride when he got a call from Hynes. He said the supervisor offered to pay him $400 to testify against Cain, get him his job back, get a job for his girlfriend, and drop criminal charges he had brought against Boatman for allegedly stealing his color TV.

After Boatman testified, he got his job back. His girlfriend also got a job at Delta Pride. And no action was brought against him on the theft charge.

Boatman clearly had nothing to gain by coming forward; on the contrary, he was putting his job at risk and opening himself up to the criminal charge brought by Hynes. “I came forward because it was on my conscience,” he testified. “I told my girlfriend ’bout every other night that it bothered me that I had lied.”

Company attorney Henry Arrington picked at inconsistencies in Boatman’s story. Where was he when Hynes paid him the bribe money? Why didn’t his girlfriend hear their conversation when she was standing two feet away? Boatman floundered for answers, but stuck to his story.

Hynes, on the other hand, looked confident on the stand. He flatly denied that he had bribed Boatman. Then why, Doolittle asked him, didn’t he press the theft charge against Boatman? “I tried,” Hynes insisted. “I called to Greenville four times about the case. They said they didn’t know where Boatman was.”

Doolittle looked surprised. “But you knew where he was. He was at the plant every day. Why didn’t you tell them to come pick him up?” Hynes offered no real explanation.

The next morning, after the hearing was over, police showed up at the Delta Pride plant and arrested Fred Boatman for theft. Less than 24 hours after he testified against the company, he spent the night in jail.

Singing Spirituals

The message seemed all too clear: If you mess with the company, you better watch out. It was a message that Rose Turner took up at a meeting with Delta Pride workers that same night. “Remember y’all, just because we got this contract don’t mean the fight is over,” she said “It’s just starting. Look at Fred Boatman. He just wanted to tell the truth. He had nothing to gain; he had everything to lose. He told the truth, and asked for forgiveness—and tonight he’s sitting in jail.” “Uh-huh! ” shouts one member. “Tell it! Tell it!” adds another.

As with so many of the troubles in the catfish industry, the fate of Fred Boatman harkens back to the days of slavery. Whites still call the shots and make the money, and blacks still do the work and speak up at their own risk.

And, as in the days of slavery, whites still complain that blacks just don’t work hard enough. Never mind that the catfish industry offers crippling work at poverty wages—the real problem is welfare. “We have a subculture of professional indigents,” confides one catfish manager who asked that he not be identified. “Government programs have made it too attractive not to work.”

You don’t have to travel far in the Mississippi Delta to find the plantation past. Down the road from Delta Pride is Florewood, a 19th-century plantation lovingly restored to its former glory. There are 27 buildings in all: the planter’s mansion, overseer’s house, cotton gin—even the privy and the poultry house. On the entire 100 acres, however, there is not a sign of where the slaves lived, not a single building to mark their presence. It is as if they never existed—or as if their lives merit less attention than livestock and outhouses.

The Cotton Museum, located in the Visitor’s Center, likewise pays scant attention to the central importance of slaves in the history of cotton. Slaves, in fact, are mentioned only once in the entire museum — on a plaque that defines the plantation system as “a type of agricultural organization in which slaves were employed under unified direction to produce a commercial crop.”

One building on the plantation that does make a passing reference to the slaves is the church — “where slaves would hold worship and sing their spirituals.” It is the romanticized image of the happy slaves, singing away their sorrows under the benign gaze of a white god.

On a sweltering Saturday afternoon in the breathless heat of a Mississippi July, hundreds of friends and family members packed the St. James Missionary Baptist Church in Indianola for the funeral of Ruthie Mae Robinson. She had worked at Delta Pride for nine and a half years, and died of a heart attack on July 4 at the age of 38.

The simple white church stands just off Highway 49 on a dirt road a few miles south of the catfish plant. The altar overflowed with flowers brought by Robinson’s co-workers. People sat in the pews, weeping softly, as Rose Turner stepped up to speak. “Miss Ruthie Mae was a good woman,” she said. “Her life will speak for itself.”

Then the Reverend R.L. Reed began the eulogy. He started slowly, almost painfully, but his words gradually gained momentum. “It’s all right to die,” he said. “It’s all right to die. Death is a place we go to ease our suffering and our pain. We say, ‘Lord, when my misery gets too great, call me home.’” Reed began to gasp for breath with each sentence and a deep rattling shook in his voice, as if the words were being wrenched from him by some force beyond his control. People screamed and wept; the entire congregation seemed to vibrate in the heat. A woman cried out and collapsed in the aisle; she was carried out by three men.

“The Lord knows she worked hard to support her children!” Reed shouted. “The Lord knows she worked hard! Her strength was her faith in God. Our strength is our faith in God!”

He raised his hands above his head, his voice rising to a deafening crescendo. “Now she has gone on to everlasting peace! Heaven is everlasting peace. It is the paycheck for the worker who has done the job. And we will carry on, we will do the job, until we have Heaven, our everlasting peace, here on Earth.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.