This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 3, "Fishy Business." Find more from that issue here.

New Orleans, La.—Each day Danny Barker sits for several hours at the dining-room table in his small white shotgun house on Sere Street, not far from the St. Bernard Housing Project. As cars whiz by outside on Interstate 10, Barker works in longhand on legal pads or typing paper or whatever is at hand, tending to the fertile terrain of memory from his six decades as a jazzman.

At 82, Barker is the elder statesman of New Orleans jazz. Born in 1909, he has performed or recorded with Louie Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Cab Calloway, Charlie Parker, and scores of others. He still devotes his evenings to music, leading the Jazz Hounds at the Palm Court Jazz Cafe in the French Quarter. But his days are given over to telling stories and weaving tales and breathing fresh life into early jazz culture.

“For me, it was a thing to be there,” says Barker, a slender, balding man with a pencil thin mustache and drooping eyelids. “You were identified ‘specially with poor people, black and white. It’s like you saying, ‘My uncle plays with the Dodgers.’ We didn’t have that in New Orleans, but we had, 'My uncle plays with the Dixieland band, or my cousin works with Chris Kelly’s band, my uncle works with Manny Perez’ band.’ It was a thing that you were associated with — some notoriety to claim a musician.”

When Barker breaks into song, he seldom fails to capture the tale-telling flavor of his native New Orleans, whether performing a classic ballad like “St. James Infirmary” or one of his own compositions like “Save the Bones”:

We started out eating short ribs of beef

Then we finished up eating steak

But after the feast was over

Brother Henry just sat down like a gentleman

And kep’ his seat

Then I scooped up the bones for Henry Jones

’cause Henry doesn’t eat no meat.

— He's a fruit man!

Henry doesn’t eat no

—He’s an egg man!

Henry doesn’t eat no

—He's a vegetarian!

He loves the gristle

Henry doesn’t eat no meat!

What is unique about Barker as a musician, jazz historians say, is that he feels at home playing a wide spectrum of styles. “Here’s a guy who can fit in musically with anybody,” says Bruce Boyd Raeburn, curator of the William Ransom Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University. “Whether you’re talking about a Calloway big band or small combo with Billie Holliday, Danny always did the right thing. How many guys crossed over that traditionalist and modernist line with such ease—not to mention the story telling?”

Family Ties

The story telling. As a spinner of tales, Barker has few peers in jazz. He enjoys the unfolding of a fable, orally or in print, with a relish written in the smiles of his face.

Barker was raised in a sprawling clan, surrounded by music. His mother’s family, the Barbarins, boasted 40 musicians, and his uncle Paul was one of the city’s finest early jazz drummers. “All they do in the Barbarin family is talk about music, all the time music,” Barker says. “So you are destined to be a musician if you want it.”

“In New Orleans it was never a problem to have music for some social event because many of the musicians were related to one another,” he recalls. “A party was planned and the musicians came and played. There your elders would explain to you, at length, how and why different musicians were related to you. When you greeted each other after that, it was ‘Hello, Cuz.’”

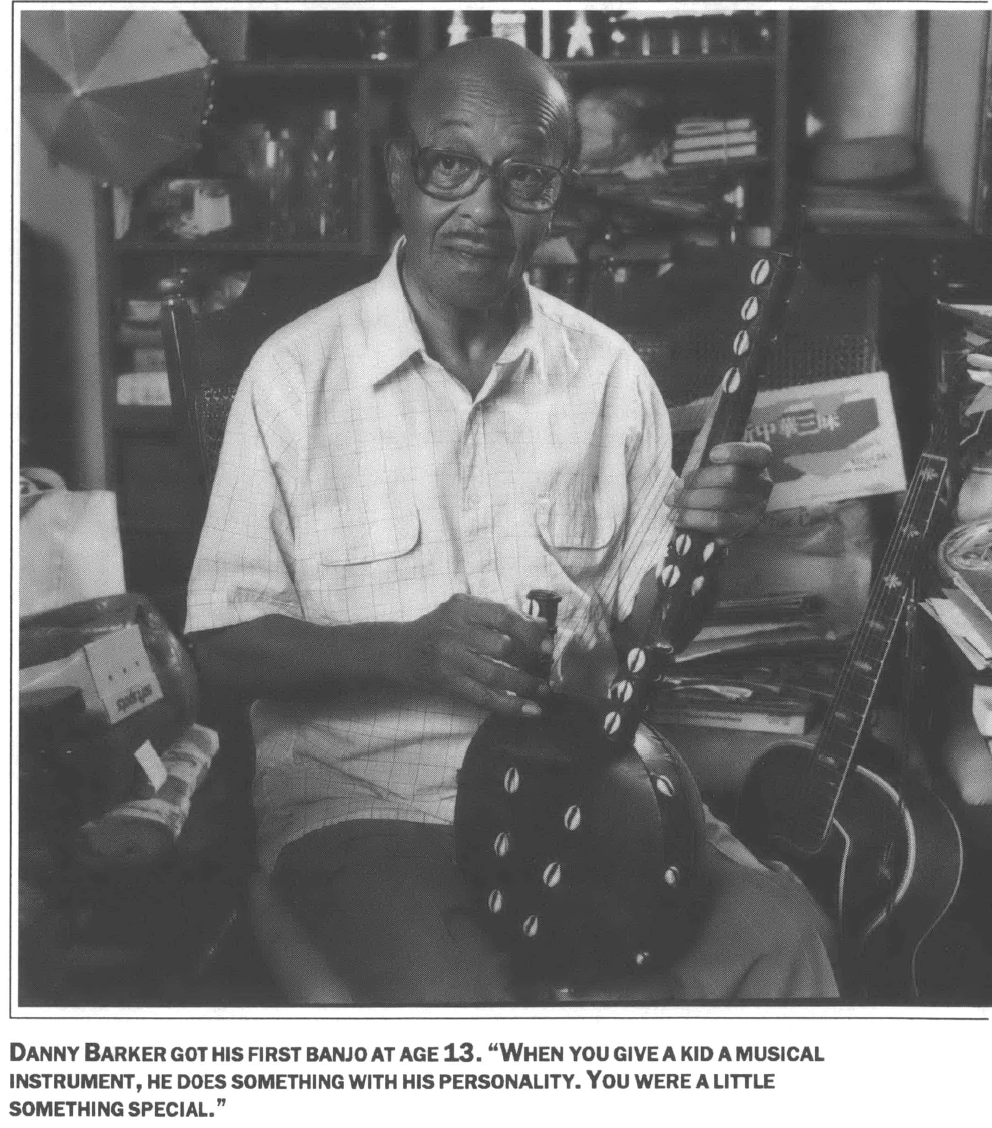

Barker got his first banjo at age 13. “I started out on clarinet, and my uncle sent me to Barney Bigard, but he left town, so I picked up my ukulele. I never connected the ukulele with the banjo. Then all of a sudden I’m playing the uke when a famous band passes. I started playing along with the right chords, I guess. An old man, Albert Glenny, had seen me fooling around with the ukulele and he called me over to his truck and said the regular banjo player was drunk and would I play a little? So they watched me and kindly smiled ‘cause I was keepin’ time, and they said, ‘Why don’t you get a banjo?’ I went and took some lessons and mother bought me a banjo.”

In those days, Barker recalls, music provided children with status and a sense of self-worth. “When you give a kid a musical instrument he does something with his personality. He becomes a figure, and he’s not so apt to get into trouble. Later on, the kids got into grass and narcotics, but in those days families would encourage you to play music. There was something about playing music that gave you something special. You were not a wastrel or a bum. Now you can be a musician and still be all those things, but generally you were a little something special when you were a musician. You had extra special talent.”

Barker grew up in a world of Creoles—descendants of free people of color—in the city’s Seventh Ward, down river from the French Quarter. The neighborhood culture was built on the skills of bricklayers, plasterers, roofers, carpenters, and cigar makers—a “self-help” environment, in the words of the poet Marcus Christian. Former Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young grew up in the Seventh Ward. So did Ernest Morial and Sydney Bartholomey, the first two black mayors of New Orleans.

The fair-skinned Creoles descended from African mothers and colonial French or Spanish fathers. In the peculiar caste system of antebellum Louisiana, they occupied a world between the slaves and slave masters; many Creoles owned slaves themselves. Creole jazzmen who lived downtown read sheet music and endowed their music with a European melodic expressiveness.

By contrast, many black musicians who lived in uptown New Orleans were descendants of slaves. They played a rougher style and learned “by ear” —imitating what they heard and capturing the heat of the blues, the echoes of slavery’s past.

“They always claimed the greatest jazz musicians came from uptown,” recalls Barker. “No, the greatest came from downtown, the Sixth and Seventh Wards— Buddy Petit, Kid Rena, Chris Kelly, Sidney Bechet, Lorenzo Tio, Alphonse Picou. The real down nitty gritty blues people were from downtown. Louis Armstrong and Joe Oliver came from uptown.”

Of Life and Death

Barker also grew up immersed in the ritual of New Orleans jazz funerals. His grandfather worked for Emile Labat, the most successful mortuary in the Creole neighborhoods, and young Danny often took part as the band ushered the casket out of the church in a mournful procession accompanied by slow, elegiac dirges —then, without warning, suddenly “cut loose,” letting the soul ascend while trumpets blared and tailgate trombones pumped out gorgeous melodic currents.

“There were countless places of enjoyment that employed musicians, not including private affairs,” Barker writes. “There were balls, soirees, banquets, weddings, deaths, christenings, Catholic communions and confirmations, and picnics at the lakefront and out in the country. There were hayrides, advertisements of business concerns, carnival season. Any little insignificant affair was sure to have some kind of music and each section engaged their neighborhood favorites.”

Most jazz musicians carry a rich store of memories, but few have Barker’s narrative gift and sense of fiction. When the talk turns to jazz funerals, he cannot resist the temptations of a bard.

“Death affects people all kinda ways,” he muses. “There was a lady had her husband stuffed. She had a special room in her house. Everybody knew Sadie Brown’s old man was there. Some Chinaman, like a taxidermist, took out all the body parts, tanned him down and stuffed him. This was in the Seventh Ward, around 1914. My great aunt took me to see his wife. I peeped in and saw Willie Brown. His eyes were kinda cocked. A lotta things happen. You see King Tut? Willie Brown was probably stuffed 30 years. You know he looked good. King Tut was a lot older.”

Barker chuckles. “This town is great for fables. So many weird things happen. Like cemetery stories.” He sits back, and the story rolls out.

“There was a girl — most beautiful-complected girl anybody’d ever seen. She’d promenade the bars, drink that booze. She tells a guy, ‘Will you escort me home?’ They leave the bar, walk two blocks to St. Louis Cemetery. There’s agate there. She says, ‘Good night,’ and makes a leap over the fence. He stands there in shock, comes back, hands wringin’ wet. He tells the bartender and asks for a double whiskey.

“Bartender says: ‘Quite a few men have come back here outta breath from that cemetery. The woman comes in here; you see her and you don’t see her. She’s got a lil’ waist like a wasp, hips like them big old horses on Annheiser Busch Beer, and her bosom protrudes like a battleship. She sits down, she orders wine sangrie—that’s bourbon, rum, wine, mixed up together. Then she just leaps up, and she’s gone with a man. It sounds like the same woman, but I’m back here mixin’ whiskey and I never see her face. You never know with these women. It’s a world of contradictions.”

Katzenjammer Kids

The rich and contradictory cultural landscape of Barker’s New Orleans neighborhood paved the way for his parallel career as a storyteller. He has published two books—an academic study called Bourbon Street Black, and his vintage memoir, A Life in Jazz. He is currently working on a sequel memoir, tapping years of stories about flush times and lean, jazz memories spun of urban folklore.

“I won a prize in the fifth-grade writing about the Katzenjammer Kids,” Barker says of his literary beginnings. “I won three dollars. I was very observant, cautious. I didn’t get into things like boozing and smoking reefer.”

Barker received a $20,000 Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Endowment for the Arts for his musical and literary accomplishment—but the prize also recognized his quiet role as a mentor to younger artists in the city.

In the early 1970s, Barker spearheaded a revival of the brass band tradition by shepherding adolescents into rehearsals for street parades with the Fairview Baptist Church Christian Band. Key members of today’s Dirty Dozen and Rebirth brass bands, who tour and record internationally, came up through Fairview, under the tutelage of Barker and his cousin Charlie Barbarin.

It all started when Barker was approached by Reverend Andrew Darby, who was searching for a way to keep teens off the street and out of trouble. “I hear these kids playing horns, and they don’t have no teacher,” Darby told Barker. “I sure would like to do something with ’em, keep ’em occupied. When I was in my daddy’s church, we had a lil’ band down there in Lower Ninth Ward, and it drew the people and we’d parade from one church to the other upon occasion. It was a nice thing. Maybe we can get these kids here started.”

Barker readily agreed to help. “I’d been thinking about it too. Lil’ Leroy Jones was playing trumpet. He was the best around the neighborhood; kids’d congregate around his garage. I said, ‘How’d you like to have a brass band? ’He said, ‘I’m for that Mr. Barker, yeah I’d like that.’ I said, ‘See how many you can get that’s capable of playing ‘When the Saints Go Marchin’ In.’ He came around my house about a week later with ten kids. And that’s how it began.”

Barker chuckles once more, recalling the Fairview boys in their musical infancy. “I put silver caps on ’em. Right away they got cocky; started challenging the other bands. We played a whole lot of things for churches—marching from an old church to a new church. All that was for little money — sometimes $20. I’d say, ‘Play ’em all, the big ones and small ones: The purpose is to learn to play and then you’ll be blessed.’”

The encouragement and practice paid off: Leroy Jones and a legion of young musicians has rejuvenated the tradition of New Orleans brass bands. Today the city has more than a dozen brass bands that compete with the rap and pop idioms dominating the airwaves. The parades meld the sound of French brass bands with a looser, African percussive beat. Feet hit the street in surging rhythm as scores of followers engulf the bands in a “second line,” dancing and gyrating as the music sweeps them along.

Young musicians continue to look to Barker as a vital link to the musical past. When Wynton Marsalis, the 29-year old trumpeter featured on the cover of Time, decided to record an album called “The Majesty of the Blues,” he invited Barker to sit in. For the cerebral Marsalis, the recording was a foray into the cultural roots of his native city; for Barker, the collaboration bridged generations, interlacing blues and jazz with sturdy, polished strokes.

New York Blues

Family ties and a strong community brought Barker together with jazz singer Louise Dupont in 1930; they have been together ever since. That same year, the couple left for New York, where Danny played with Jelly Roll Morton and Cab Calloway. He also began writing.

“You get to New York,” he reflects, “and it’s a whole new opening. An element of inspiration you couldn’t conceive in the South, where when blacks said something, whites look at you as if you have no foundation. You have an attitude you’re not qualified. In New York you had a freedom. You meet artists in the Harlem Renaissance. You see Langston Hughes, Paul Lawrence Dunbar, Countee Cullen, and they’re talking about their aspirations. There was night schools, and sculptors, and paintings. I’m playing music and hangin’ around these people.”

It was an era of ambiguities. Jazz flourished while the poor stood in bread lines. Barker read the works of Richard Wright, Hughes, Hemingway, and Twain, as well as the gritty urban vernacular of newspaper columnists like Walter Winchell.

Sitting under a photograph of himself and a young Louis Armstrong, Barker muses: “New York is not a blues town. People would sit in the audience and look at some Southern man singing hard times ’cause he lost his wife—Ohhh, I’m gonna lay my head on a lonesome railroad track—and they don’t move a muscle. ’Cause New York’s attitude was, ‘You can’t get along with Rosy? Then get Mary.’ I had a drummer, he showed me six wives he had lived with. In New York you just get rid of it. In New Orleans you linger on.”

In 1942, Barker was playing with the Cab Calloway Orchestra when Esquire magazine discovered jazz; writers sought out musicians. He helped many writers, but his own writing met with resistance from publishers. He had many pages of stories, but lacked a unified manuscript. Undaunted, Barker kept writing.

But the New York jazz scene was changing, and by 1965 Barker felt out of place in his old haunts. “Swing and traditional jazz was in decline,” he recalls. “Bebop was in the ascent. Them boys had a whole cult—forget about clothes: was Eisenhower jackets and dungarees. I’m from New Orleans. I wanna wear a silk shirt, look prosperous. And they’re into narcotics, smoking reefers and they supposed to be hip ’cause they don’t shave no more.... If you were neat, clean and dressy they look as if something was wrong with you.”

Barker returned to New Orleans, where the civil rights movement was bucking Jim Crow. Danny and Blue Lu found themselves showcased at the Jazz and Heritage Festival to a new world of adoring fans. He formed his own group and joined clarinetist Michael White in a wondrous Jelly Roll Morton revival act.

“I’ve been asked many times why Jelly was so boastful,” he remarks. “You see, Jelly was part of an era that knew nothing of press agents and publicity build-ups. Most of the famous public figures blew their own horns. It was the custom of celebrities in those early days to arrive in a city and immediately go to the main drag, where they would loudly start to boast of their ability, and then mouth to-mouth, news would spread like wildfire. Jelly pulled this stunt all along the Mississippi River, especially in Kansas City, Memphis, St. Louis, and Chicago.”

Barker’s work resurrects the ambience and environment of his own formative years as an an artist. In writings and interviews, he repeatedly returns to the cultural terrain that shaped him and the tradition out of which jazz grew.

“Before the arrival of the big insurance companies,” he writes in A Life in Jazz, “New Orleans had organizations called Benevolent Societies; some small, some large. Members banded together in these societies as protection and precaution in time of sickness, trouble, death.... Nowadays the money in the treasury barely pays the electric light bill, but the remaining members want to exit in style—New Orleans style: the big brass band, three thousand people.”

Although a traditionalist in his approach to music, Barker is no militant purist. “Jazz is constantly changing,” he says. “Jazz we hear today in New Orleans— ‘Bourbon Street Parade’ and ‘The Saints’—is music nobody wants to dance to. But New Orleans still carries on. When it hits the street, 5,000 people form a second line. Nowhere else will you see people perform like that in the street. There’s no end to what can happen with jazz.”

Tags

Jason Berry

Jason Berry is the author of Amazing Grace, a memoir of civil rights politics in Mississippi, and co-author of Up From the Cradle of Jazz: New Orleans Music Since World War II. (1991)