The Green Index

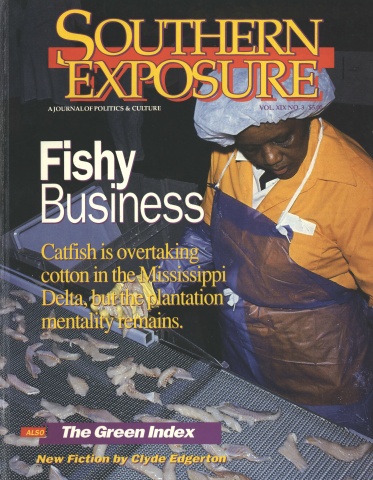

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 3, "Fishy Business." Find more from that issue here.

For many of us, the word “environment” conjures up visions of snow-capped mountains, trout streams, endangered owls, and “Save the Whale” campaigns. All too often we forget to include people, buildings, cars, farms, and factories — the stuff of human life—in our concept of “environment.”

Yet human life is inextricable from nature. Pollution from factories and farms threaten not only plants, streams and birds, but our own and our children’s health. Car exhaust and acid rain corrode our homes and make it hard to breathe; pesticide runoff poisons the fish farmers eat; and industrial pollution, generated by the billions of pounds and dumped in our air, water, and soil, devastates communities, exposes workers to diseases like cancer, and ultimately damages the larger ecosystem which affects us all.

The Green Index, published by the Institute for Southern Studies and Island Press, is designed to make the connections between pollution, the natural environment, and the health of workers and communities. Drawing on 256 indicators ranging from toxic waste in the air to voting records in Congress, we have compiled a state-by-state ranking of “environmental health” that acknowledges the links between pollution and disease, between poisons and poverty.

The rankings reveal some clear regional patterns:

The industrial states of the Northeast and Great Lakes continue to pay a heavy environmental price for decades of manufacturing, but they have begun to tackle their serious water and air pollution through progressive legislative policies.

The Rocky Mountain states have less total pollution, but their lush natural resources are threatened by their increased reliance on dirty energy industries like mining and by their frontier approach to planning and regulation.

The Farm belt states rely on the soil and water for their economic survival, but decades of chemical assault on the land have left the region with contaminated groundwater, a dwindling farm population, and worsening public health.

New England and the Far West fare best in the rankings; despite smog, depleted forestland, toxic waste sites, and ocean pollution, both regions can boast of durable political support for innovation and conservation.

Of all the regions, the South ranks worst. In the overall standings based on all indicators, Southern states occupy the bottom seven positions. The region has 9 of the 17 states with the highest per-capita emissions of toxic chemicals, 9 of the 12 producing the most hazardous waste, and 108 of the 179 facilities that pose the greatest risk of cancer to the people who live near them.

The region ranks particularly low in two categories: toxic and hazardous waste, and community and worker health. Such poor standings are no coincidence. The South has long condemned its residents to unsafe workplaces and unhealthy living conditions; the region boasts 10 of the 12 states with the highest premature death rates, and all but two Southern states suffer from above average rates of job-related deaths.

In recent decades, however, the region has also become the nation’s dumping ground. Many of the world’s deadliest waste management companies have intentionally built landfills and incinerators in poor, rural, and often black communities. Knowing that residents are desperate for jobs and tax revenues, the waste handlers enter these impoverished areas cloaked in the guise of economic salvation, promising better times through toxic waste.

The tactic amounts to environmental blackmail, pressuring the poor to sacrifice their health and the health of their children in return for low-paying jobs. In the end, the toxic dumps burden poor communities with waste they didn’t produce, drive away clean industries that could provide genuine, lasting development, and create new health risks in areas already hard-hit by high infant mortality and premature death rates. As our accompanying report on the battle over a hazardous waste incinerator in one North Carolina county makes clear, the deadly game of jobs-versus-health often centers on the politics of race. When the waste management firm ThermalKEM decided to burn hazardous waste in Northampton County, it set out to divide and conquer the black majority with promises of good jobs and better social services. The controversy has split the black community, highlighting the racism and economic injustice that so often underlie environmental issues.

By documenting such realities and tying them together, the Green Index brings home a broader, community concept of environmental health. The child next door may have trouble breathing because of fumes from a nearby papermill; a friend who works in a factory maybe exposed to dangerous chemicals on the job; our county commissioners may be selling away our future by building another landfill.

Such environmental threats are pervasive, but there is still time to protect our communities. In Northampton County, black and white residents have come together to forge a grassroots movement determined to push public and private officials to shift their priorities from profits to people. They know that the health of their environment — safer jobs and cleaner communities — offers the real key to meaningful economic development. “One of these days,” says State Senator Frank Ballance, “industry is going to find out that what’s good for the economy and the environment and the average person is good for them.”

AIR SICKNESS

Residents of Port Neches, Texas live in the shadow of the U.S. factory that poses the highest risk of cancer from a single chemical. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the Neches West Chemical Plant owned by Texaco pumps more than one million pounds of butadiene into the air each year, putting its neighbors at a 1-in-10 risk of cancer.

For years, townspeople have watched friends and relatives in their thirties and forties die of the disease. They complained repeatedly to federal officials, but their pleas fell on deaf ears.

Finally, state officials sent Texaco and the neighboring Ameripol-Synpol plant notices last year that they were violating emissions of cancer-causing butadiene and styrene. To date, the federal EPA has done nothing to punish the corporations for their illegal emissions.

The residents of Port Neches are not alone. Half the people in the United States are routinely exposed to polluted air, and many of the pollutants came from industries that poured 2.5 billion pounds of toxic chemicals into the air in 1988 alone.

Yet in case after case involving major corporations, EPA has done nothing to regulate, much less stop, most chemical air emissions. Twenty years after passage of the first Clean Air Act, the federal government has yet to set standards for thousands of chemicals that industry pumps into the air we breathe. Of the 300-odd toxic chemicals companies are required to monitor, 123 are carcinogens — yet EPA has set emission standards for only seven.

Even with the passage of the 1990 Clean Air Act, a full-scale crackdown is still years away. According to an EPA report, setting federal pollution standards “has become increasingly difficult with frequent litigation, and consequently few regulatory actions have been completed in recent years.”

While corporate lawyers hold up action, EPA has contented itself with simply adding up the pounds of toxic chemicals released into the atmosphere by major industrial producers. Even then, the agency relies on company measurements, as required by the 1986 Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act.

Despite its limitations, the act gives citizens access to information about 300 chemicals released into their communities. For two years, EPA has published the totals in its Toxic Release Inventory (TRI), a survey of chemical discharges to water, air, the land, public sewers, or injection wells.

TRI data for industrial emissions reveal some disturbing highlights:

Total Air Toxics. The six states with the largest amounts of toxics released into the air are Texas, Ohio, Tennessee, Louisiana, Utah, and Virginia. The top polluters are chemical producers, steel and other metal manufacturers, paper makers, and the auto industry. The nation’s single largest industrial source of air toxics is the AMAX Magnesium complex in Tooele, Utah. The second largest, Kodak’s Tennessee Eastman in Kingsport, emits 40 million pounds, mainly chemicals like acetone and methylisobutyl ketone that irritate the eyes, nose, throat, liver, and kidneys.

Toxics Per Capita. Ten of the 15 states that suffer from the heaviest toxic emissions per person are in the South. One third of West Virginia’s air emissions are in Kanawha County, and half of that amount, or five million pounds, comes from the Union Carbide plant in Institute — a sister plant to the one that killed at least 3,500 people in Bhopal, India. In February 1990, a small amount of methyl isocyanate, the Bhopal killer, leaked out and injured seven workers in Institute. Among the toxics the county’s dozen chemical facilities dumped into the environment in 1988 were 1.6 million pounds of known carcinogens.

High-Risk Factories. Texas has the most plants posing the greatest cancer risk from exposure to a single chemical — 33 out of 179 on the list. Next comes Louisiana with 17, California and Georgia with 11 each, and Washington with 10.

What We Don’t Know

Right-to-know laws have given residents of polluted areas an important tool in their fight for cleaner air. But the Toxic Release Inventory only monitors manufacturing processes; it exempts utilities, government-owned plants, mining operations, and, ironically, waste management firms.

In general, states that host factories producing loads of toxins are also the ones with other hazardous facilities. Louisiana is a perfect example. The state ranks 50th in high-risk factories per capita, 47th in total pounds of air toxins, and 48th on a per capita basis. Its “Chemical Corridor” from Baton Rouge to New Orleans produces a fifth of the nation’s chemical pollution, and has earned the nickname “Cancer Alley” for its above-normal rates of cancer. The state also attracts poisons from all over the country to its waste facilities — none of which is counted in the TRI.

For example. Marine Shale Processors in Morgan City burns 100,000 tons of hazardous waste each year, making it the largest commercial incinerator in the country. The company first burned oil field waste, then began illegally incinerating other wastes like mercury, DDT, and cyanide without updating its permits. At the same time, the number of respiratory problems, birth defects, miscarriages, and cancers in the area shot up. Neuroblastoma, a fatal nervous-system cancer, struck five children among 64,000 residents near Marine Shale; the normal rate is one in 100,000.

But since Marine Shale is a waste handler rather than a manufacturer, the TRI tracks none of its emissions. The inventory also omits thousands of chemicals that pose serious harm to human health and the environment. For example, the TRI does not monitor sulfur dioxide, even though the chemical is the chief precursor for acid rain. In September 1990, a huge cloud of sulfur dioxide from the Tennessee Chemical Company floated over nearby McCaysville, Georgia. The damage was immediate. At least six people went to the hospital with respiratory distress, and within two days hundreds of acres of trees and other vegetation were scorched brown — the result of instant acid rain.

Acid Rain

Acid rain is created when the sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides produced from burning fossil fuels react with water in the atmosphere. When the water falls to earth as rain or snow, it wages chemical warfare on the environment. Fish and trees die, marble or limestone buildings corrode, and people with breathing or heart problems face increased health risks.

New England is the hardest hit by acid rain. Hundreds of lakes and streams from New Jersey’s Pine Barrens through New York’s Adirondacks to the forests of Maine have become acidic solutions. Acid rain also threatens states far beyond the Northeast. More than a fifth of the lakes in the Appalachians as far south as Tennessee and North Carolina contain acidic pH levels, as do a sixth of the lakes and streams in northern Wisconsin and the Michigan peninsula.

Coal-burning power plants account for 70 percent of all sulfur dioxide emissions and 25 percent of nitrogen oxides. Ohio, with its heavy concentration of coal-fired plants, ranks 46th in sulfur dioxide emissions and 40th in acid rain. West Virginia ranks 50th in sulfur dioxide, generating twice the pounds of the next worst state, Indiana; the two states reap the consequences with acid rain rankings of 48th and 47th respectively. Kentucky is 47th in sulfur dioxide emissions, but thanks to prevailing winds, most of its acid drifts hundreds of miles eastward.

To stop acid rain and revive the damaged ecosystem will require substantial new initiatives, beginning with the control of coal-burning power plants and vehicle emissions. But while acid rain corrodes the dome of the U.S. Capitol itself, lawmakers inside from the big coal and auto states have blocked acid rain regulation proposed by lawmakers from New England.

State legislators from New England are also well ahead of the federal government in controlling carbon dioxide, the leading cause of global warming. The escalating volume of carbon dioxide — the byproduct of burning fossil fuels — threatens to melt the polar ice caps, hasten the rise in sea levels, distort rainfall patterns, kill plants, and eventually destroy human life.

With only five percent of the world population, the United States produces 25 percent of all carbon dioxide. About a third of that share comes from our vehicles, and another third comes from electric utilities. But instead of tackling the problem, President Bush has chosen to stall, claiming more data are needed.

In the vacuum created by the federal government, several Northeastern states have taken concrete steps to curb greenhouse emissions. Last year, for example, the president’s home state of Connecticut became the first to pass a global warming law that penalizes new buildings that fail energy conservation standards and requires new state-owned vehicles to average 45 miles per gallon by the year 2000. Bush’s adopted home state of Texas, on the other hand, continues to generate more carbon dioxide than all of Canada or the United Kingdom.

The Smoking Gun

The biggest source of “greenhouse gases” that threaten to raise temperatures worldwide is the automobile. In fact, more than half of all air pollutants come from our cars and trucks.

Leaky air conditioners in vehicles account for one-fourth of the chlorofluorocarbons that are eating a hole in the ozone layer. Billions of pounds of nitrogen oxides from our tailpipes return to earth as acid rain. Smog and carbon monoxide from auto exhaust also cause respiratory ailments, ruin crops, and promote heart failure and cancer. Finally, the car is the driving force behind the petrochemical industry, the biggest source of environmental poisons not on wheels. Without doubt, the automobile is the most lethal weapon in America.

The Clean Air Act of 1970 targeted emissions from motor vehicles, especially lead and carbon monoxide. But since more Americans now drive more miles — four times as many as in 1950 — the air is still badly polluted. “All the progress we are making through fuel efficient technology is being eaten up by growth,” says James Bond, executive officer of the California Air Resources Board.

As a result, Americans continue to pay a high price for air pollution. The American Lung Association estimates that 120,000 people die unnecessarily or prematurely each year from motor vehicle exhaust, more than twice the number killed in traffic accidents.

Residents living along the heavily traveled corridor between New York City and Washington, D.C. face the greatest risk. Maryland, Delaware, and Pennsylvania rank with New Jersey and New York among the worst 10 states for smog and carbon monoxide pollution— and among the worst for cancer deaths.

But the danger extends to Southern states as well. Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, Virginia, North Carolina, and Texas promote their pristine environments to new arrivals, but 40 percent or more of their citizens live in cities with repeated smog violations.

California, where smog was first diagnosed, also faces enormous problems. A1989 study concluded that the Los Angeles basin could save $9.4 billion in health and lost-time costs if it met federal clean air standards. The state already spends more than twice as much as any other state per person on air pollution programs, but the results have been disappointing. Smog levels have increased for most counties, and last year 90 percent of state residents breathed air violating ozone and carbon monoxide standards.

The failure of smog-control programs underscores the need for a mass transit alternative to the automobile. “The greatest potential for reducing smog lies in providing people with first-class options for getting around,” says Ken Ryan, transportation chair for the Sierra Club.

San Francisco, Boston, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Washington, Buffalo, Portland, Sacramento, and San Diego have all recently begun or expanded their commuter train systems, but big spending for highways remains the norm. Thirty-seven state governments spend even more on roads than they bring in from gasoline and vehicle related taxes. Thirty-one put less than $3 into public transit for every $100 spent on highways.

WATER POLLUTION

Scattered among the mountains of Lincoln County in rural West Virginia stand scores of tiny, dilapidated houses. Most aren’t more than a stone’s throw from one of the many creeks that flow from the Mud River, but few have running water.

With no money to install pipes or septic systems, many families must haul water from streams contaminated by mining, industrial, and household wastes. Kidney disease, worms, and parasites arc common. “The water’s no good,” says a woman who has just brought her daughter home after a bout with pneumonia. “I’ve had a miscarriage and a stillbirth and this baby’s sick all the time. I’m afraid to stay here.”

County health officials say thousands of families in rural Appalachia risk their health every time they take a drink. “The vital connection between poverty and sickness is bad water,” says one. “So much of the disease comes from the wells. It starts with the baby. You’re basically mixing a formula with sewer water.”

Few natural elements affect our health and well-being as profoundly as water. The essential ingredient of life, it flows in vast underground aquifers and covers three-quarters of the earth’s surface. But this bountiful supply is now polluted enough to cause 10 million deaths a year worldwide.

Half the drinking water consumed in the United States comes from surface water— rivers, lakes, streams, and reservoirs. Although their pollution has been regulated since the 1950s, one-fourth of these waters now fail to meet their designated uses for drinking and recreation.

The other half of our water supply comes from underground aquifers, or groundwater. Like surface water, groundwater is susceptible to contamination from agricultural and industrial chemicals. It is also vulnerable to leaking landfills, waste lagoons, and underground tanks. Groundwater moves slowly, often along an unpredictable path. and contaminants may concentrate in plumes for years, making cleanup difficult or impossible.

Toxic Toilet

A third of the toxic chemicals that industry dumps into surface water comes from direct end-of-pipe discharges. The remaining two-thirds pass through public sewage treatment facilities and then into our waterways. Because these facilities cannot neutralize most toxic pollutants, EPA requires generators to cleanse, or “pretreat,” their waste before it reaches the public sewage system. However, a recent survey by the U.S. General Accounting Office reveals that 41 percent of the pretreating companies exceed discharge limits.

Companies get rid of even more toxic chemicals by simply injecting them underground, which jeopardizes the purity of groundwater. Altogether, industry flushed away 2.2 billion pounds of toxic waste in 1988 through direct discharge into surface water, transfers to sewage systems, or underground injection.

Direct Discharges to Water. The 150-mile section of the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, the toilet for at least 136 major industrial facilities, receives more toxins than any other stretch of water in the country. In fact, Louisiana has one-half of all chemical waste directly discharged into surface waters by EPA-monitored companies. Many local residents rely on the Mississippi for their drinking water and suffer a higher than normal incidence of cancer and miscarriages.

Direct Discharges Per Mile. Louisiana has the most concentrated discharge, followed by Tennessee and several Eastern Seaboard states. The waste from Maryland’s two biggest water polluters, W.R. Grace and Bethlehem Steel, continues to foul the once-fertile Chesapeake Bay. Even though thousands of fishers have lost their jobs, Bethlehem Steel has used its workforce of 8,000 as leverage to negotiate reduced fines and repeated delays in meeting emission limits for various chemicals.

Toxic Transfers to Sewers. Missouri sends the most chemicals into public sewage systems — 77.6 million pounds, or 14 percent of the national total, with three-fourths of the waste coming from St. Louis County alone. Sewage systems in Illinois, New Jersey, California, Texas, and Virginia also receive large volumes of industrial toxins, each accounting for seven percent or more of the U.S. total.

Per-Capita Transfers to Sewers. The Dakotas, several Rocky Mountain states, and Alaska rank best; they lack the infrastructure or inclination to manage industrial waste through public sewage systems. By contrast, almost a third of all toxic chemical emissions in New Jersey pass through its public sewage treatment plants. The sheer volume helps explain why the state ranks 45th in sewage systems violating EPA standards, 44th in investment needed for adequate treatment facilities, and 2nd in per-capita spending to protect water resources.

Toxics Injected Underground. Texas and Louisiana create 69 percent of all toxins pumped underground. Louisiana injects the most chemicals per capita and per square mile, while Texas pumps the highest volume. In Alvin, Texas, Monsanto recently increased by 50 percent the amount of acrylonitrile, a probable carcinogen, it sends underground. In Louisiana, Shell Oil pumped an astonishing 152 million pounds of hydrochloric acid into the ground in 1988.

Ranked according to these and four other indicators for toxic wastewater, Tennessee emerges as the worst state overall. The biggest generators are chemical companies, led by DuPont’s facilities in Memphis and New Johnsonville and Kodak’s huge Tennessee Eastman plant in Kingsport. But a dozen other firms from food processing to textiles and paper making also send a million or more pounds of toxins to sewage systems, rivers, or underground caverns each year.

Too often, getting state and company officials to control, much less reduce, these wastes remains difficult, even when drinking water quality is at stake. Consider the example of Avtex Fiber in Virginia, another Southern state that ranks in the bottom five for overall water-borne toxins. The sole producer of carbonized rayon for the Defense Department and the space program, Avtex Fiber dumped zinc, chlorine, sulfuric acid, PCBs, and other toxic wastes directly into the Shenandoah River for over a decade. Despite evidence of chemical pollution in nearby wells in1981, high toxin levels in fish in 1985, and a PCB spill in 1986, the state Water Control Board and EPA issued only weak warnings.

Finally, after the Natural Resources Defense Council threatened to sue the company in 1988, the state decided to sue Avtex itself. In November 1989, following new PCB emissions from the company, Avtex was shut down and fined $6million. The cleanup is expected to cost at least $100 million.

“So far, the state has failed to understand the basic problem with environmental pollution — that the price for environmental damage will be extracted,” says David Bailey, director of the Environmental Defense Fund in Virginia. “If you don’t make the company pay for it, the environment will pay for it, and the citizens bear the cost.”

Toxic Drains

In addition to industrial chemicals, other pollutants — detergents, motor oil, fertilizer, construction waste, pesticides— wash off lawns and city streets into storm drains or sewers. Throughout the nation, aging sewage plants can no longer handle the mounting waste load. In 1988, some 6,250 of the nation’s 15,600 treatment facilities reported water quality or public health problems. In Massachusetts, 12 billion tons of raw or partially treated sewage reach Boston Harbor each year—about 500 million gallons per day.

Such waste is taking a heavy toll on the nation’s lakes, rivers, and streams. Ten percent of all river and stream miles are already ruined; they can no longer support their designated uses for fishing, recreation, or drinking. Twenty percent only partially support their designated use, and another 10 percent face imminent danger of becoming impaired.

The states ranking worst on fresh water quality are in the Great Lakes and Farm belt (Ohio, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa) or mining regions (West Virginia, Montana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Alaska). Among the best are Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia —even though Alabama and Mississippi ranked among the worst 10 states for drinking water violations, and Alabama and Georgia ranked 42nd and 41st in toxic discharges to surface water.

The rankings on water quality can be deceptive, because each state decides how much to test and how to define which waters can support their designated use. Minnesota, for example, calculates that nearly two-thirds of its rivers and streams fail to meet designated uses, dropping its rank to45th — but its monitoring includes a detailed analysis of fish tissue, a procedure ignored by many states. Dioxin, a deadly poison that can cause birth defects, miscarriages, and nerve damage, is another significant threat to surface water quality. In 1908, when Champion International built the South’s first paper mill on the banks of the Pigeon River in North Carolina, the river was clear and full of trout. Today, the Pigeon is discolored, practically dead, and contaminated with dioxin from Champion’s wastewater. Four major rivers in Arkansas, recipients of waste from paper companies like Nekoosa Papers in Ashdown, also contain dangerous levels of dioxin. Arkansas ranks 42nd, with 58 percent of its rivers and streams impaired.

Agriculture poses the greatest single threat to inland waters. Pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers, other nutrients, and sediment wash, dribble, or blow into the water, impairing 55 percent of the nation’s river miles. A study by the U.S. Geological Survey released last year reveals that 98 percent of the streams tested in 10 Midwestern states contain the pesticides atrazine and alachlor, both likely carcinogens.

Agriculture is also a major consumer of inland waters, especially in the Midwest and Rocky Mountains. Seven of the dozen states with the nation’s highest per capita consumption of water (Idaho, Wyoming, Nebraska, Colorado, Nevada, Kansas, New Mexico) are among the dozen that rely most heavily on artificial irrigation for their crops; as a result, several are also responsible for draining valuable aquifers.

Deep Throat

Underground aquifers in the United States contain 16 times as much water as the Great Lakes. They feed public water systems and private wells, and supply billions of gallons of free water daily to mining, industrial, and agribusiness concerns. In North Carolina, for example, the Texas gulf phosphate operation sucks out more water than is consumed by the entire city of Charlotte. Groundwater pollution comes from many sources. Poisons leach from Superfund or other waste sites, and agricultural chemicals seep through the soil. Saltwater invades when coastal wetlands are damaged. Underground storage drums — including over 300,000 leaking gasoline tanks — leak benzene and other dangerous substances. In 1980, at the behest of Senator Bennett Johnston of Louisiana, Congress exempted companies drilling for oil and gas from hazardous waste disposal laws, allowing them to dump “non-hazardous” waste mud into open pits. That decision has poisoned groundwater, as sludge and brine from oil drilling have seeped into underground supplies. Seven oil and gas producing states — Louisiana, Texas, Wyoming, Indiana, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Ohio — are dotted with injection wells that leak wastes into shallow aquifers. The seven states are also among the worst dozen for toxic chemicals pumped underground by manufacturers. Groundwater protection is largely left to the states. Florida not only collects data, but also controls underground injection and storage tanks, regulates septic tanks, and protects aquifers. The Sunshine State ranks 9th nationally for its per-capita spending to protect and improve water quality.

Florida needs all the help it can get. It ranks 49th in pesticide contaminated groundwater, 47th in reliance on groundwater for drinking, 46th in public water systems and 39th in sewage systems in noncompliance, 46th in impaired lakes, and 43rd on the composite toxic wastewater score. Overall, Florida takes last place in our clean water indicators. The dying Everglades, symbolic of the state’s problems, supplies the aquifer that feeds south Florida’s ballooning population, but state officials have stood by (or even helped) as the sugar and oil interests pollute, siphon, and otherwise destroy these unique wetlands.

Drink Well

Drinking water sources all across the nation face similar threats. But EPA regulations only apply to public water systems that serve 25 people or more for at least 60 days a year. Private wells, which supply one household in seven, are not monitored under the Safe Drinking Water Act, even though evidence suggests many are contaminated. In Florida, for example, over 1,000 wells were condemned following the discovery of groundwater laced with the pesticide ethylene dibromide. Many rural states that depend the most on private wells also rely heavily on septic tanks, which can contaminate groundwater. Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont score in the bottom five on both indicators. The problems are even worse in rural Farmbelt communities that also face pesticide contamination, or in Southern states like Tennessee, Mississippi, and Kentucky which allow huge injections of toxic chemicals beneath the ground.

No state depends more on wells for its drinking water than North Carolina. The Tarheel state also ranks 30th in surface and groundwater that may be contaminated and49th in households using septic tanks. Some areas don’t even enjoy the luxury of septic tanks. One small community of black families in Camden County, North Carolina lives in a swampy area where sewage from outhouses runs through open drainage ditches less than 10 feet from their wells.

West Virginia ranks dead last for surface water quality, with 80 percent of its streams and 100 percent of its lakes impaired. The state also ranks 39th in households served by wells, 47th in households dependent on septic tanks, 47th in water used for non-drinking purposes, 43rd in spending for water quality, and 46th in investment needed for adequate sewage facilities.

“When we first moved back here, we had to haul water from the creek,” recalls one Lincoln County mother of nine. “We really had it tough. We have a bathroom and a well drilled now, but the water’s no good. It turns everything brown.” For too many West Virginians, a drink of cool, clean mountain water goes with the myth of country living, not the reality.

COMMUNITY AND WORKPLACE HEALTH

In Plaquemine, Louisiana, a small town 30 miles down the Mississippi River from Baton Rouge, Etta Lee Gulotta discovered 40 cancer cases in a five block radius. Her husband died of lung cancer, even though he never smoked.

In nearby St. Gabriel, pharmacist Kay Gaudet calculated that local women suffered miscarriages at twice the average rate. The vinyl chloride gas emitted by neighboring chemical companies, she learned, is known to cause cancer and is suspected to poison embryos.

Next door in Geismar, a predominantly black town with homes only a few hundred yards from factories emitting dangerous gases, 9 of every 10 children suffered serious respiratory problems.

For residents of towns along the “Chemical Corridor” that stretches from Baton Rouge to New Orleans, the connection between pollution and health problems is all too clear. When the environment is sick, people get sick. Despite our efforts to create walls between ourselves and our waste, pollution seeps in.

In Louisiana, where the petrochemical industry churns toxins into the air and water each day, cancer deaths stand well above the national average (rank 46). An unusually large share of Louisianans work in jobs that expose them to serious diseases (rank 48). They also work in jobs in some of the most highly toxic industries (rank 46).

Indeed, the proportion of Louisiana citizens who do not reach age 65 because of illness or injury — the premature death rate — is one of the highest in the nation (rank 47). At the same time, private employers in the state furnish only half of their workers with insurance (rank 49), and per-capita spending on public health is barely 40 percent of the national average (rank 43).

In Louisiana and throughout the country, the people hardest hit by pollution are often the poorest. They tend to live downstream or downwind of dirty industries, or in areas that lack adequate plumbing, sewage disposal, and public health programs.

Conduct a survey in your community: Are waste dumps and heavily polluting industries located on the same side of the tracks as poor or working-class neighborhoods? Are wealthy neighborhoods located upwind from the dirt and danger? Money flows in the opposite direction of pollution.

Now conduct a survey of your local workforce: Are the most hazardous factory jobs held by people of color? By those with the least education? By contract or temporary workers with few benefits or protections?

Disposable Lives

How a company or a state regards the safety of its poorest people says a great deal about its commitment to environmental health. Not only is the environment of working and poor people shaped by high-risk jobs and toxic communities, they are also the first to feel the effects of inept policies that allow individual actions to become public hazards. Like the canaries once sent into the mines to test the air for deadly gases, their pain and sickness should sound the alarm for all of us. The 23 indicators we chose to measure community and workplace health emphasize this relationship between public policy, pollution, living conditions, and human health. The results are distressing— the nation’s community and workplace health is ailing, and no state can claim a clean record.

Not a single state ranked in the top half in all indicators. Even Massachusetts and Minnesota, which ranked first respectively in workplace health and community health, have significant health hazards. Massachusetts ranks 39th for cancer deaths; Minnesota ranks 36th in public health spending and 27th in homes without adequate plumbing. At the other extreme, Alabama and Arkansas rank below average on nearly every indicator.

On a national scale, the health data suggest that workers and the poor are considered disposable:

One person in seven under age 65 — 33 million people — has no medical insurance, either through a private plan or Medicaid. The proportion jumps to one in five for African-American children and to almost two in five for Latino children. Regardless of race, families with incomes under $25,000 are only one third as likely to have insurance coverage for their children as families earning over $40,000.

Each day in America, more than 100 babies under age one die — 39,500 babies in 1989. The nation’s infant mortality rate of 9.6 deaths per 1,000 live births is the second highest in the industrialized Western hemisphere. At the same time, 11 percent of the gross national product goes for medical care, a larger share than any other developed nation.

Using federal data, the National Safe Work Institute in Chicago estimates that 70,000 workers are permanently disabled each year and another 71,000 die annually from occupational diseases like black lung and asbestosis. Yet the share of the federal budget devoted to agencies regulating workplace health has dropped by a third since 1981.

The National Safety Council says that workplace injuries and accidents kill another 10,500 people each year. In addition, the Bureau of Labor Statistics calculates that each day some 11,000 workers are injured seriously enough to lose work time or to be put on restricted work duty. The rate of lost-time injuries has increased by 39 percent since 1974.

Uneven Standards

Taken together, such numbers form a powerful indictment of our national health care system in general — and of workplace safety regulators in particular. Just as EPA is charged with monitoring environmental health, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration is responsible for ensuring workplace safety— yet OSHA has only one-twentieth the budget and few of the enforcement tools at EPA’s disposal.

The U.S. General Accounting Office reviewed the performance of OSHA and found the agency riddled with problems. Among its conclusions:

Inspections are few and far between. “Even employers in high-hazard, targeted industries are rarely inspected.”

OSHA sanctions “provide limited deterrence to employer noncompliance,” since the average assessed penalty for a serious violation was only $261 in 1988.

Follow-up is unreliable. OSHA uses employer reports to verify compliance rather than conducting its own follow-up inspections.

Existing regulations are inadequate. “Safety and health standards fail to cover existing hazards or keep up with new ones.”

Like EPA, regional OSHA offices vary greatly in their pursuit of a safe environment. OSHA offices in Texas, for example, are among the weakest at penalizing companies for workplace deaths. The agency fined Brown & Root, the giant Houston-based contractor, a mere $16,285 for OSHA violations related to 22 deaths between 1974 and 1988.

Texas OSHA has been even more reluctant to tackle the huge petrochemical industry. Regional administrator Gilbert Saulter admitted he “was surprised” to learn that an average of 40 workers a year were dying from accidents in the industry. The state never even bothered to inspect the Phillips Petroleum refinery in Pasadena from 1975 to 1989 — the year an explosion killed 23 workers and injured 232, making it the worst industrial accident in the 20-year history of OSHA.

Some Southern states, like North Carolina, have simply circumvented OSHA by setting up their own agencies to monitor workplace safety — yet many homegrown substitutes have never been fully certified by the federal government because they lack the staff or funding to enforce minimum federal standards.

The federal failure to set tough health standards is even more apparent in the area of worker compensation, the employer-financed insurance programs designed to shield companies from negligence suits and to pay injured workers substitute wages and health benefits. The current hodgepodge of compensation systems breeds inequities between the states and results in different treatment of similar injuries and illnesses.

A study by the Orlando Sentinel documented problems in Florida’s system that are common to many states: Insurers and employers harass those who file claims, send them to company doctors (often to be misdiagnosed), drag cases out, stall or terminate payments arbitrarily, cut off medical reimbursement, and pressure workers to settle for less money. Many workers are never even told they’re entitled to worker compensation, but are instead paid from cheaper company insurance policies.

Infants and Medical Access

Rankings in the Green Index suggest a link between workplace and community safety: Companies that injure their workers are also likely to pollute their neighbors. At the community level, the high correlation between a company’ s regard for employee health and its respect for pollution standards means that people on both sides of the factory walls have an interest in protecting one another.

In Humphreys County, Mississippi, 33 of every 1,000 babies die before the age of one — an infant mortality rate surpassing many Third World nations. Southern states account for 9 of the worst 10 states for premature deaths and 7 of the worst 10 for infant mortality.

Why are Southerners so likely to die prematurely? Poverty certainly plays a role, condemning many to poor nutrition and inadequate health care. But Southern death rates rank even higher than those in poor rural areas outside the region. The Green Index rankings show a strong correlation between high death rates and heavy minority populations — reinforcing the conclusion that race plays a major role in isolating people from resources needed for a healthy life. If you're not part of the “good ole boy” network, you’re relegated to the margins of society — which is also where the waste dumps, landfills, and Superfund sites are often found.

Mississippi has lowered its infant mortality rate over the past few years, but it still ranks among the worst 10 states. With one out of four of its citizens lacking medical insurance, it also ranks last in this crucial indicator of health care accessibility.

South Carolina ranked worst for infant mortality in 1989, with a rate of 12.5 deaths per 1,000 live births. The Palmetto state hosts far more than its share of radioactive, hazardous, and toxic waste. It also ranks 50th for premature deaths, 48th for people without insurance, and 39th for doctors per capita. Like seven other Southern states, it ranks among the bottom 10 for homes that lack kitchen facilities, toilets, or hot water.

The states with the best infant mortality rates (Rhode Island, Vermont, Massachusetts, Maine, Minnesota, Iowa) also do well in rankings on insurance coverage and Medicaid programs. In all but one case, these same states are among the top 15 for maximum disability payments and for the percent of unemployed workers receiving benefits, indicating a general progressive tilt toward public programs serving the truly needy.

In contrast to these and other states in the Northeast and Midwest, the South trails in benefits for the disabled and in passing laws to protect worker rights. Even though the region is home to 6 of the 12 states with the largest share of their workforces in high-risk jobs, it also has 7 of the 12 states with the most people lacking insurance coverage and 6 of the 12 with the lowest compensation for unemployed workers. West Virginia — the notable exception in each area — leads the South in union members, public health spending, and disability benefits. But with its dependency on coal mining, West Virginia also leads in unemployment and occupational deaths.

A Worker’s Lobby

The rate of union membership among manufacturing workers is an important indicator of the workplace environment. With OSHA doing such an inadequate job of setting and enforcing safety standards, unions must often act as health-and-safety lobbies. Several studies also show that the rise of non-union, contract labor has worsened the job safety records of various industries.

The Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union (OCAW) found that workers for subcontractors of major petrochemical firms suffer an injury rate 2.5 times that of the major firms. The increasing use of non-union, inexperienced contract workers has led to several disasters, including 17 deaths at ARCO Chemical in Houston last year and the lethal explosion at the Phillips Petroleum refinery in Pasadena in 1989.

In another study, the Detroit Free Press determined that while half of Michigan’s autoworkers are employed in supplier plants, they experience two thirds of the industry’s serious workplace injuries and fatalities. According to the newspaper, the Big Three automakers have relatively fewer incidents than their suppliers because they have less turnover and a more unionized, better-trained workforce. By not allowing employers to cut corners at the expense of their health and safety, union members protect their job environment.

Although unions have played an important role in defending the health of workers, they cannot tackle the problem alone. The answer to the alarming failure to protect workplace and community health is not simply better enforcement and more compensation for these victims of an unhealthy environment. As with other forms of pollution, the answer is prevention. We must stop the causes of disease, injury, infant mortality, and occupational death; set standards that eliminate hazards; and deliver medical and educational resources that focus on prevention rather than remediation.

Tags

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)