Fishy Business

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 3, "Fishy Business." Find more from that issue here.

Few creatures are so completely identified with the South as the catfish. Southerners have been eating the mud-dwelling fish for more than 4,000 years, ever since the Native American culture called Poverty Point flourished along the Mississippi River. Long a favorite food of the poor, the mudcat still endures a reputation as the dirtiest of fish, a bottom feeder that will eat whatever comes along.

Over the past two decades, however, the lowly catfish has become big business. As markets for cotton and other traditional crops have withered, farmers from Louisiana to South Carolina have flooded their fields to make way for catfish ponds.

The switch from agriculture to aquaculture has paid off. Backed by a strong marketing campaign to improve its swampy image, farm-raised catfish is now a booming industry that raised $2 billion last year. Catfish ranks as the fifth most-consumed seafood in the nation after tuna, shrimp, cod, and pollack.

Almost all of the growth has taken place in Mississippi. The state produces three-fourths of all catfish consumed nationwide, mostly in the Delta counties of Sunflower and Humphreys, where catfish has actually surpassed cotton as the leading crop. Last year Mississippi farmers raised 624 million catfish in nearly 95,000 acres of ponds, netting more than $360 million.

From the start, farmers in the Delta have tightly controlled the new venture from top to bottom. Through a business structure known as vertical integration, a small group of 400 farmers has run the entire industry, from the mills that feed the fish to the factories that prepare them for market.

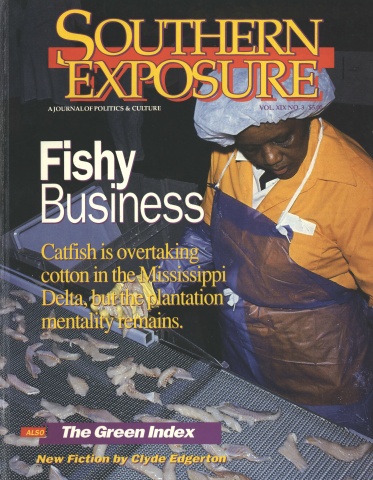

As the articles in this special section of Southern Exposure suggest, catfish farmers are the new bottom feeders. They live off the poverty of the Mississippi Delta, yet they share few of their profits with those who do the dirty work. Ninety percent of the 6,000 workers who process and package catfish are poor black women, many of them single mothers. Most receive barely $4 an hour for their labor.

Like their counterparts in the poultry industry, catfish workers are driven at a dangerous, breakneck pace. According to a 1988 internal memo from Delta Pride, the largest producer of catfish in the nation, head saw operators are expected to cut off 60 catfish heads a minute—as many as 43,000 fish a day. Those who fall behind, the memo warns, “will be considered to be in violation of Work Rule #12, which requires them to work productively and efficiently.”

As a result of this ruthless emphasis on production, many catfish workers suffer from repetitive motion disorders, painful injuries to the hands and arms that, left untreated, can leave them permanently disabled. Workers at Delta Pride report that when their injuries prevent them from complying with Work Rule #12, the company simply fires them.

Nor has government come to the aid of injured workers. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has set no safety standards for repetitive motion disorders in the industry, even though a recent federal investigation revealed that scores of workers currently receive no medical care for their injuries.

Fortunately, in the midst of the racism and poverty of the Delta, there are the stirrings of a genuine and broad-based movement for change. Last December, nearly 1,000 women and men at Delta Pride won a three-month strike for better wages and working conditions. Now, inspired by their courage, a coalition of community leaders from across the Delta are working to reforge the links between the labor and civil rights movements. The plan, organizers say, is to reform the catfish industry while empowering poor citizens to develop their own, community-based economic alternatives.

It is a plan that will become increasingly urgent in the coming years. Like poultry, catfish and aquaculture will continue to grow, driven by the demands of health-conscious consumers. McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken are reportedly considering plans to offer catfish on their menus, and Brown-Forman, the company that makes Jack Daniels and Southern Comfort, is pouring $6 million into a bass fish farm in the Delta.

But as with poultry, it seems, consumers must be prepared to consider some tough questions about the food we buy. Where does “healthy” fare like catfish come from? And whose health, in the end, is being served?

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.