This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 3, "Fishy Business." Find more from that issue here.

Isola, Miss.—Larry Cochran was in trouble. For 20 years he had farmed his piece of land in Humphreys County, ground his father and grandfather had worked before him. He grew 1,000 acres of cotton and soybeans, but he was deep in debt and getting deeper.

Rising interest rates and international competition were creating insurmountable obstacles for Southern cotton and soybean farmers like Cochran; it was harder to borrow money for equipment and supplies, and it was harder to sell the product for a profit. In 1979 row-crop revenues in Mississippi were $737 million. By 1983 they were down to $181 million.

Cochran knew he needed a new crop, and needed it fast. So like a few of his fellow farmers in the Mississippi Delta, he flooded several of his fields and stocked them with catfish.

“I started messing around with fish back in 1978,” recalls Cochran, a big, squared-off man with a rugged jaw and an easy laugh. “Me and my brother put in four ponds. Then, the row crops like to broke me. I was still paying off my debts years later.”

By 1985, Cochran had given up on row crops altogether and was growing over two million pounds of catfish in 33 ponds. “Fish are the only thing that saved me from going belly-up,” he says. Cochran was not the only farmer saved from foreclosure by switching from cotton to catfish. Across the Delta, farmers were abandoning their traditional row crops, heralding a dramatic economic shift from agriculture to aquaculture. Within a decade, a handful of white planters created an entire industry that they control from top to bottom, from the mills where they buy their feed to the factories that buy, process, and market their fish.

Known as vertical integration, this top-down control of each stage of the process has enabled farmers to keep their costs down and their prices high. The result has been hefty profits: Last year catfish generated $350 million in the Delta, much of which went into the pockets of some 400 farmers.

Despite the financial success of catfish, however, the Delta remains the poorest region in the nation. The development of the catfish industry simply enabled a small group of white planters to continue their domination of political and economic life in Mississippi —much as their ancestors ruled the land when it was first cleared and cultivated by black labor.

“The catfish industry is very typical of the plantation mentality,” says Malcolm Walls, a leader of Mississippi Action for Community Education. “In many ways, the catfish industry has simply replaced cotton with catfish. The rest remains the same.”

Bigger is Better

It was not easy to subjugate the Delta to a plough a century ago. The land was exceptionally inhospitable, thick with swamp, canebrake, and malaria. The job of clearing it fell chiefly to black men using crosscut, two-man saws to cut down hardwood trees, mules to drag them out, and fire to bum them.

For white settlers, the reward for clearing the land was the extraordinary fertility of the Delta soil. Each spring brought a flooding of the Mississippi River, which spread out across its banks from Memphis to Vicksburg, depositing its burden of rich topsoil and leaving layer on layer of the finest farmland in the country, delivered free of charge. In some places the alluvial topsoil is over 25 feet deep.

For the first half of the 20th century, that soil grew the best cotton in the country. With large holdings of land, and sharecroppers to work it for almost nothing, Delta farmers made money. Slowly but surely, agriculture became agribusiness. As farming began to require more expensive equipment and chemicals, banks encouraged planters to borrow more money and increase the size of their operations. Farms got larger and larger, and fewer and fewer.

“They were giving away money back then,” one farmer recalls. “They’d come right out to the fields, you didn’t even need to go into town. They’d draw up the papers and write you a check right there in the truck. They made it hard to turn down.”

But the bigger-is-better strategy ran aground in the late 1970s, as interest rates soared and export markets dried up. The demand for Mississippi cotton fell, and banks started calling in their loans and putting a freeze on new money for farmers.

Up until then, there was nothing unique about the plight of Delta farmers. It was the same one faced by farmers all across the nation who had bought the get-bigger or-get-out theory of farming. But unlike the millions of farmers elsewhere who went under during those lean years, many Delta farmers were saved from ruin by the land itself. Much of their property consists of soil known as buckshot—heavy clay that drains poorly, making it no good for growing cotton, but great for farming fish.

It is not cheap to start a catfish farm. A 1988 state report estimated that it costs at least $400,000 to dig eight ponds covering 15 acres apiece, fill them with water, stock them with two-inch fingerlings, and feed the fish for a year until they are ready for harvest. If the fish don’t die of disease or a sudden drop in the pond’s oxygen content before they can be sold, the farmer can anticipate an annual profit of almost $1,000 per acre—about $120,000 a year for a typical eight-pond operation. The high start-up costs might have been an impediment to catfish farming in other parts of the country, but Delta banks are used to doing business in six figures. When it looked like there might be some money to be made growing catfish, Delta farmers did not blink an eye. They headed for the bank and began digging ponds.

Top-down Control

Turner Arant was one of the first Delta farmers to see the commercial potential of catfish. He stocked his first pond in 1962 to give his family somewhere to fish. In 1965, he made his first commercial harvest.

“I decided to market those fish because there were a bunch of them in there and they were getting big,” recalls Arant, a broad-faced man dressed in a sport shirt and slacks. “I called this little processing plant over in McGee, Arkansas and they sent a harvesting crew and a live-haul truck over here, seined the ponds, loaded the fish, and hauled them 90 miles back to McGee. A couple of weeks later they sent me a check for a little over $3,000. That was like $30,000 today. So I got interested in the business commercially and immediately built a few more ponds.”

As cotton got worse and worse, catfish looked better and better to Arant. “It was getting impossible to make money off of cotton, and every year I’d look at my cash flow on cotton and see that the rest of the farm was carrying it. I said, ‘Heck, I need to just quit growing cotton.’ So I did, and that freed up a lot of equipment and time. I started building more ponds.”

But Arant didn’t stop there. He and other farmers quickly realized that they could make more money if they could control their costs. Once ponds are dug and stocked, the single greatest expense to catfish farmers is feed, which generally eats up half of all operating costs. At the height of the summer, when fish consume the largest quantities of feed, farmers can spend $30,000 every two weeks to keep their ponds fed.

In the early days, catfish farmers were at the mercy of national feed corporations like Ralston/Purina that controlled prices and supplies. Determined to break free, a group of farmers formed a cooperative feed mill called Producer’s Feed in 1976. Shareholders get their feed for just about cost, and at the end of the year they even get a rebate. Plant management is hired by a board of directors, made up of farmer/shareholders. It was the first step on the road to complete vertical integration. “Vertical integration is the thing that has stabilized the catfish industry and made it profitable,” says former Humphreys County extension agent Tommy Taylor. “Producer’s Feed allowed the farmer to get the quality and quantity of feed he wanted. That was critical, because feed companies in other places were really putting it to us. By the end of the first week Producers Feed was open, the price of feed had dropped from $300 a ton to $250.”

Once the feed mills were in the hands of farmers, they could effectively set their own price for feed. It did not take them long to realize that they could also increase their profits if they could set the price their fish brought at the doors of the processing plant. By 1979, two multinational corporations, Con-Agra and Hormel, both heavy players in the agricultural sector, had already opened processing plants in the Delta.

Turner Arant and 40 other farmers got together and decided the time had come for a processing plant of their own. In 1981, they took out a cooperative loan and started up a farmer-owned processing plant called Delta Pride. Today it is the largest processor of catfish in the world.

Arant now has 1,600 acres of ponds, owns shares in both Delta Pride and the Delta Western feed mill, and manages 400 acres of ponds for a limited partnership composed of investors from all over the country. Arant sold the limited partnership the land for its ponds, as well as75 shares of Delta Pride stock, which he priced at $1,000 a share. He is also paid an annual salary as the manager for the partnership. “Catfish have been good to me,” Arant says.

For white farmers, the profits can indeed be tremendous. When farmers opened the Delta Western feed mill in1979, for example, its shares fetched about $20,000 apiece. By 1990 shares went for $450,000, according to one shareholder. Last year Delta Western sold approximately 200,000 tons of catfish feed worth $50 million.

Such large-scale operations are a long way from the early days of the catfish business, when county extension agent Tommy Taylor answered many a call at three in the morning from panicked farmers whose fish were dying. Farmers knew Taylor would always be right over, even if “right over” was 25 miles away, down five miles of dirt road in the humid dead of a mosquito-filled night.

“I held a lot of hands back in the early days, because farmers had no one to ask about their problems,” says Taylor, a short man with a sizable paunch. “No one knew anything about catfish, and I became an expert because there was no one else to do it then.” Working on his own, Taylor put together the first catfish lab in Humphreys County—a sink, six pails, and a microscope in an empty room behind his office on the top floor of the shadowy old courthouse in Belzoni.

Since then, Taylor has watched catfish grow from a back-room business to a lucrative industry. “I’m telling you that the one thing that has made the difference is vertical integration,” he says. “Right now, the farmer controls the feed, the fish, the processing, and the marketing, and that’s what keeps us strong.”

Taxes and Research

Humphreys County runs from Isola, just below its northern border with Sunflower County, to Louise, just above the border with Yazoo County to the south. More catfish are grown here than anywhere else in the world. Billboards featuring a drawing of a huge channel catfish mark the county lines, its gun-metal blue, gray, and silver colors looking clean and appetizing. “Welcome to Humphreys County,” the billboards proclaim, “Catfish Capital of the World.”

The movers and shakers in the world of catfish farming can be found at the Pig Stand, a little barbecue joint at the side of Highway 49 on the outskirts of Belzoni. This was where policy for the catfish industry got shaped. Deliberations go on every day but Sunday, and the pickup trucks come and go throughout the day.

Many white Delta farmers don’t do much of the actual hands-on labor of catfish farming; mostly what they do is manage. Like their fathers and grandfathers before them, they take the financial risks, give the orders, and make the profits. A goodly portion of each day is spent in town making deals with other farmers, picking up the mail, talking, telling stories, and staying on top of the paperwork.

Most Mississippi cotton farmers have been living off of federal tax dollars for years. Each family that forms a cotton corporation may receive a federal subsidy of up to $50,000, and families often form multiple corporations using different combinations of relatives. Without the subsidies, there would be hardly a boll of cotton grown in Mississippi, yet many farmers bitterly denounce poor Delta women for having children out of wedlock to increase the size of their welfare checks.

They lambast black residents for being more interested in collecting welfare benefits than in working an honest day. “I was behind a colored girl in the checkout line the other day and she paid for a box of salt with a $1 food stamp, then got outside and threw the box away ‘cause she just wanted the change,” grumbles one indignant planter.

While taxpayers have not been called on to support Delta catfish to the same degree as Delta cotton, some tax dollars have gone into building the processing plants owned by white farmers. Grain Fed, a $6 million processing plant, was built in the little town of Sunflower with the help of $1.6 million in federal Urban Development Action Grant funds. And in 1989, the Farmers Home Administration approved a guaranteed $2 million loan to help finance the $7.5 million Fishco processing plant outside Belzoni.

Julian Allen, owner of the South Fresh processing plant at Baird complains bitterly about the use of federal money in the plants, even though his own company was built with the help of $220,000 in bonds issued by Sunflower County. “We used real capital dollars to build our company, and Delta Pride did the same thing when they started,” Allen says. “But most of these other plants used UDAG grants, and it’s the government that has put them in business, under-capitalized and under-funded.”

Catfish farmers have also received millions of dollars in direct support from Mississippi State University, which employs scientists to research every aspect of the industry from diet to disease. The Delta Branch Experimental Station, located at Stoneyville, employs five full-time researchers and maintains over 60 ponds, all funded by state taxpayers.

Those resources are at the beck and call of the industry. “Because of the unique situation here, where the extension service works directly with both the researchers and the farmers, we have a good flow of information both ways,” says Randy MacMillan, a fisheries specialist at the station. “Research is directly delivered to the catfish farmer, and his problems are prioritized and given to the researchers to work on. What we do here is try to translate our work into practical benefits for the farmer.”

MacMillan is on his way to Isola, an hour’s drive through the Delta, responding to a call from a worried farmer who thought the fish in one of his ponds were suffocating from a mysterious ailment known as hamburger gill. As he drives up to the levee, the pond lies placidly under the sunshine, turtles on the banks jumping into the water with a wet plop. The water’s edge is dotted with fish floating in the shadows, white bellies up.

“When you start to see this many dead fish in a pond, you know you’ve got a real problem,” MacMillan whispers. “This guy’s got trouble.”

MacMillan nets a fish, revealing its mushy, ailing gill. Suddenly, a surge of life passes through the fish, which arches its back and spikes MacMillan with its dorsal fin. “Gosh dam it,” he exclaims, blood oozing from a puncture in his palm. “That’s one of the hazards of this job. Getting finned doesn’t just hurt, it can give you fishmonger’s disease, which attacks muscle bundles and can actually be life-threatening.”

Black Labor, White Profits

For all his work out at the ponds, MacMillan is still an academic. Every farm worker knows how to handle catfish spikes: Rub the slime from the belly of a catfish on the wound and both pain and swelling ease immediately. The worst spiking, workers say, is when the fin breaks off in the wound. “If that catfish spike breaks off in your hand, your whole arm goes numb,” says Victor Taylor, a black farm worker. “If you get stuck like that by yourself, don’t try to drive to the doctor. No sir. ’Cause you won’t make it. Just lay down and wait for it to pass to where you can drive.”

Taylor has worked for Jack Reed, a white planter, for all 64 years of his life. He was dressed in a khaki cotton work shirt and old jeans. He had only a pair of yellowed, snaggle-teeth left in his mouth, one up and one down. He sat behind the wheel in his battered pick-up, on the levee of one of Mister Jack’s ponds.

Most of the physical labor of catfish farming is performed by black workers like Taylor. They maintain the ponds, cut the grass around the levees to keep the snake population down, feed the fish, and maintain equipment like generators, aerators, tractors, and nets.

The toughest work comes at night, between May and November, when the oxygen levels in each pond must be monitored three or four times each evening. Once the sun is down, algae in the pond stop photosynthesizing — they consume oxygen but do not release it. If the oxygen level in the pond falls below two parts per million, all the fish will suffocate within hours unless the pond is aerated promptly.

The work is monotonous and lonely. Oxygen checkers sleep during the day, and check the ponds every two hours at night—not a farmer’s idea of fun. Billy Ed Tinnan used to check on his own fish. It wasn’t easy waking up in the early morning every two hours, stumbling out into the humid night. It was hard farming.

“It gets pretty bad out there,” Tinnan says. “The mosquitos are so thick on top of the levees that you can rub your hand down your arm and just leave a trail of blood. They aren’t the worst, though. I hate are the midges. They don’t bite, but they get in your nose and throat. Man, when you swallow one of those, you’ve got to have something to drink to get that thing unstuck.”

Tinnan eventually tired of checking his ponds every night, so he hired Fish Management Inc. to do it for him. The company manages over 100 catfish ponds for Tinnan and six other farmers. Oxygen checkers make more than minimum wage, but not a lot more.

Charles Kirksey says he puts 10,000miles a month on a company pick-up checking ponds for Fish Management. Every night from 9:30 p.m. to 7:30 a.m. he checks as many as 72 ponds, three times each, taking oxygen readings and writing them down on a clipboard. He works 70 hours a week, and makes a little more than $4.25 an hour.

Clouds of midges swirl over the ponds in the beams of his headlights. “They’re awful when you get one in your eye,” Kirksey says. “They get up against your eyeball and they’re hard as hell to get out. Your eye drives you crazy all night.”

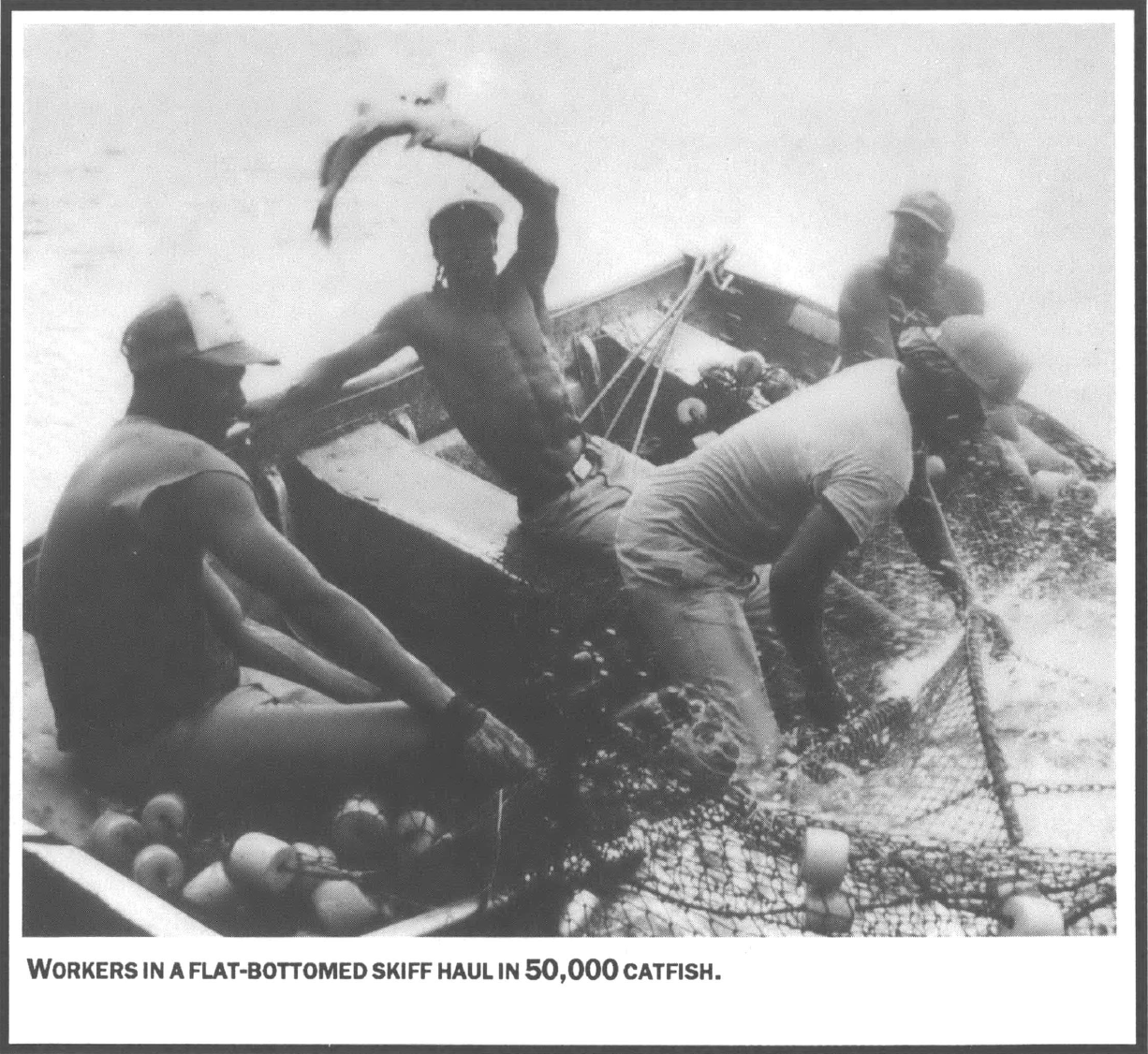

When catfish are ready to harvest, farmers employ crews of black workers to “seine” the ponds. Tractors on either side drag 1,200 feet of net across the water while workers wade behind it, pushing it along. Larry Cochran employs a seining crew full-time, working his pond and those of seven other farmers who pay him for the service. It is enough to keep the crew busy year-round.

An hour wading through four feet of water under a broiling Mississippi summer sun is not a pleasant way to make a living. Pond banks are crawling with water moccasins, and fin spiking is common. But there’s not much else in the way of jobs in the Delta, and those on the seine crews tend to come back for more.

“These are good boys and they work pretty hard,” says Redbug Sykes, a short, balding man who manages the seine crew for Larry Cochran. “I’ve got more or less the same crew we had last year, and the year before that.”

Land = Power

Sykes shows more respect for his workers than most farmers, who are prone to describe the labor force in terms reminiscent of the plantation. “There are a lot of colored who just don’t want to work,” complains Bob Bearden, who farms an immense spread of 102 ponds with his two brothers. “Now they’re not all that way. We got a boy raised here on the farm and he’s just a nice boy. He’s colored. We probably pay him $20,000 a year.”

Bearden then launches into a long description of “welfare cheats” who have never worked a day in their lives. “They’ve got brand-new houses paid for by the government,” he says, the top three buttons of his shirt unbuttoned, three gold chains nestled in the hair on his chest.

The Beardens run one of the largest catfish farms in the world, with more than 3,500 acres underwater and 55 full-time employees. They work a seining crew 200 days a year, and the hatchery that stocks their ponds produces over 100 million fry.

The family is headed up by Dillard Bearden, one of the most powerful men in Humphreys County. Dillard’s father came to Isola in 1925 and bought 200 acres. The family now owns 5,000 acres. “The Beardens have such a big operation, if they cough twice they’re behind,” says Tommy Taylor, the former county extension agent.

For catfish farmers like the Beardens, money and land easily translate into political power. Dillard has served for years as a county supervisor, and many of his neighbors speak bitterly of his influence over local business and social services. He and other farmers have long used their sway to help maintain separate private schools for white children in the Delta, condemning black children to learn what they can at underfunded public schools.

In neighboring Sunflower County, Lester Myers serves on the board of the all-white Indianola Academy and sits on the Delta Council, an influential organization of business powerbrokers. He also runs Delta Western, the largest producer of catfish feed in the world, and farms 500 acres of catfish ponds.

“The quality of the public education system has really, really eroded away,” Myers says. “The whole public education system eroded away.”

But wasn’t that because white leaders like Myers pulled out the entire white school-age population all at once and sent their children to a private academy? “That too,” Myers says equably.

Muddy Waters

Each April, the catfish industry sponsors the World Catfish Festival in Belzoni. The event attracts 40,000 people to a town of slightly more than 3,000, and features a flea market in the two downtown streets of the county seat.

The annual festival is just a small, local component of a broad strategy to market catfish to the seafood-consuming sector of the American public, a job that required some doing. If there was ever a fish with a poor reputation among people with money in big cities, it was the catfish. Lots of people in the North and West are born, live, and die without ever tasting one bite of catfish, or wanting to.

That was never the case in the Delta, of course, where wild catfish have been a staple since native Americans inhabited the region around 2000 B.C. Catfish caught in the wild have a strong, muddy, fishy taste. In their natural state, catfish are omnivores, the goat of the fish world— they will eat anything they can swallow. Much of their lives are spent rooting around in the mud at the bottom of rivers and ponds for bugs, plants, smaller fish, and whatever else they can find. Many Southerners, having eaten wild catfish all their lives, prefer the natural muddy taste, but people in other parts of America like their fish to be blander.

A whole lot blander. Farm-raised fish, on the other hand, are taught from the beginning of their lives to come to the surface to eat. Feed for adult fish comes in small, round, floating pellets about the size and color of dry dog food. The pellets are distributed by a blower mounted beneath a hopper on the back of a pickup truck. Once a day, a farmhand drives the truck slowly along the pond’s levee and the grain-based feed is blown out over the water. A catfish raised on this mechanized diet has a firm, white meat that is neutral in taste, bland enough that it will pick up the flavor of any herbs and spices with which it is cooked.

But catfish offers attractions more substantial than its neutral flavor. Catfish are low in cholesterol, and feed for healthy catfish contains none of the antibiotics that are given to pigs, cows and chickens on most farms. The water in catfish ponds comes from artesian wells and has repeatedly tested free of agricultural pollutants.

It also makes good economic sense to grow catfish as opposed to other kinds of livestock: A cow needs almost eight pounds of feed to produce a pound of meat, a pig needs four pounds, and a chicken needs three, whereas two pounds of feed will produce one pound of catfish.

But in order to learn the benefits of farm-raised catfish, the American public had to be convinced to try it. The industry recognized it would not be easy, but it persisted—and, thanks to the tools of modem advertising, it succeeded.

In 1987 farmers in the Delta organized the Catfish Institute to serve as the marketing arm of their new industry. Funded by a “check-off” of six cents per ton at two farmer-owned feed mills, the Institute hired a Manhattan ad agency to present catfish to upscale consumers in big cities as a desirable choice for dinner.

Under the guiding hand of Belzoni resident and Ole Miss graduate Bill Allen, the Institute did an extraordinary job of accomplishing its goal. The industry poured $1.3 million into the ad campaign, and by all accounts it was money well spent. A 1989 consumer survey showed that of all the people who had heard of farm-raised catfish, almost half knew it was “different” than other catfish.

The Institute also got a lot of free advertising in the form of magazine articles and television reports. In 1987, an industry survey counted more than 2,100 stories about farm-raised catfish worth an estimated $1.5 million in comparable advertising.

Catfish sales began climbing, and the price per pound rose steadily as catfish gained increasing acceptance across the nation. National consumption of grain fed, farm-raised catfish grew from virtually zero in 1965 to nearly 400 million pounds in 1990.

Bad Taste

With more and more people willing to try catfish at least once, the industry has placed an almost fanatical emphasis on maintaining quality control. As farmers see it, a person from Boston who has lived a lifetime without ever tasting catfish is only going to give it one chance. If that person gets a “bad” fish, there will never be a second opportunity.

Stanley Marshall is known far and wide in the Delta for his ability to detect “off-flavor” fish. A short, blond-haired man with a trim mustache and a ready smile, Marshall samples fish at the Delta Pride processing plant, sniffing and tasting to weed out any fish fouled by too much blue-green algae in the pond.

On a typical afternoon in the Delta Pride kitchen, Marshall takes a fish from a farmer, puts it in a paper sack, and pops it in a microwave. When it’s done, he opens the sack and sticks his nose into the steam billowing out through the tear in the bag. “Whew, man,” he exclaims, wrinkling his nose. “Smells like diesel fuel.”

The farmer’s face falls. More than$50,000 worth of fish will have to stay in the pond, swimming around until they taste better. “We did have a diesel spill in that pond one day,” he admits. “I just wanted to know how bad it was.”

“Well, give it a couple of weeks and bring one in,” Marshall tells him.

Such slight variations in taste underscore the fragility of catfish farming. Despite its financial success, the industry is not immune to unexpected fluctuations. Every few years, there is trouble—too many fish in the ponds, too few contracts at the processing plants. Twenty-six catfish farmers went under during one such period in 1984, and others just managed to hang on until they signed a contract with Church’s Fried Chicken for more than 54 million pounds of fish.

To stabilize prices, farmers formed the Catfish Bargaining Association in 1989.Over 85 percent of the area’s farmers signed up, along with most of the processing plants. The association fixed the price that processing plants must pay for their fish at 80 cents a pound.

By this summer, however, the industry was entering another rocky phase. Processors competing for markets were charging less for their fish, and in return offered farmers less than the association prices. Many farmers, caught with ponds full of fish, have defected from the association and sold below the 68-cents-a pound break-even point. If the price wars continue, industry observers say more farmers and processing plants could founder next year.

Despite periodic slowdowns, farmers expect the demand for catfish to continue to grow in the coming years. They look to a future modeled on the poultry industry, which now ranks as the biggest agribusiness in the South. The average American eats 65 pounds of chicken each year, compared to 16 pounds of seafood.

“There’s no reason why we can’t enjoy the same success that came to the poultry industry,” says Sam Hinote, former president of Delta Pride. “We’ve just scratched the surface. If you look at the growth of the industry from 1970 on, you can predict the future. In 1970, the whole industry processed about five million pounds of catfish. By 1980 that had risen to 46 million, and by 1989 it was up to 342 million pounds. My projections are that we’ll be processing over a billion pounds by the year 2000.”

But while catfish farmers profit from the boom, most black residents who provide the labor remain undisturbed by the financial success. If the industry invested some of its profits back in the community, catfish might help lift the Delta out of poverty—but that doesn’t appear likely to happen in the near future. As it is, the rising demand for catfish will benefit a small minority of Deltans, leaving the majority untouched.

“I’ve watched catfish farming around here go from a few ponds to what it is today,” says Bobby Whelan, an Indianola teacher and musician who chopped cotton as a teenager with many of the men currently working as farm laborers on the ponds. “The farmers are making a lot of money, but the people working in the plants and at the ponds are still making low, low wages. It’s black people making the thing work, but they’re the only ones not making money out of it.”

Tags

Richard Schweid

Richard Schweid is a former reporter with The Tennessean in Nashville. (1991)