This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 2, "Punishing the Poor." Find more from that issue here.

Ivan, Ark. — Even when the central Arkansas weather is dry and the Georgia Pacific lumber mill in nearby Fordyce is running at full tilt, Anita Ford can only count on $400 a month in earnings from her husband. With the additional $475 she receives in Aid for Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and food stamps, there’s barely enough money to feed her four children and keep gas in the pickup her husband drives to the mill.

When the thunderheads started rolling in this April, the rumble of trucks hauling freshly cut pines on the dirt roads near Ford’s home slackened. It was a sign she would have to get by on less as the spring rain held up timber cutting and shortened shifts at the mill.

“If the weather’s bad the bossman thinks nothing of saying ‘you can’t work this week,’’’ Ford says from the front room of her trailer. “You just expect it.”

But Ford wasn’t expecting a letter from her caseworker announcing a cut in AFDC payments, with the loss of food stamps and Medicaid benefits soon to follow. Like more than 1,000 other women in the past year, Ford had been “sanctioned” by the Arkansas Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) for “failing to cooperate” with the state’s workfare program known as Project Success.

Ford’s benefits were cut after she failed to make the 12-mile round-trip drive to Fordyce for adult education courses — a requirement to receive welfare benefits under the program. Ford had no objection to the twice-a-week classes aimed at helping her pass the GED exam; she simply couldn’t afford to go. Although Project Success reimburses participants at the end of every month for transportation costs, Ford didn’t have the $6 it took each week for gas. And like virtually all rural areas in the state, there was no public transportation available.

“The money we have is money to survive — it goes to electricity, water and food,” Ford says as she sits forward in her chair. “I would have gone if they could have given me $3 each time in advance. Even though Fordyce is just a hop, skip and a jump, I can’t do it.”

Ford’s 10-year-old daughter had recently shown some signs of scoliosis during a screening at her elementary school. Finding gas money for a more thorough exam nearly 70 miles away in Little Rock before her Medicaid privileges were revoked became Ford’s main concern. After her benefits run out, she has a rather tenuous plan for assisting her children if they fall sick.

“I’m going to pray to God I can get to Little Rock because they don’t turn kids away at Arkansas Children’s Hospital,” she says. “But you’ve got to get gas to get there. This whole thing has taken a mental and a physical toll — it just weighs on me. This program is not helping us at all.”

Welfare Recycling

Ford is not alone in her opinion of Project Success. Although Governor Bill Clinton proposed and lobbied for the Family Support Act of 1988 — the federal legislation requiring workfare programs like Project Success nationwide — the chronic shortage of child care and transportation plaguing the state’s predominantly rural counties has made it more of a burden than a benefit for many of the nearly 15,000 participants.

“There’s been no success in this project,” says Jo Ann Cayce, an advocate for the poor who has organized relief efforts for the past 39 years in rural Dallas County. “It was misnamed.”

Cayce and other critics complain that AFDC recipients are being forced to participate in a program that is flawed from start to finish. Assessments intended to gauge the skills of participants before they are placed in training programs either miss the mark or don’t take place at all. Arkansas’ AFDC payments are the sixth lowest in the nation, making it difficult for women to remain in the program when unexpected expenses — no matter how slight — force them to miss training sessions and face the threat of sanction. Women who make it through the education program face unemployment figures that often reach double digits in many rural areas.

Those who find work often earn minimum wage — or less — with few health care benefits. If one of their children gets sick, they end up back on welfare to pay the doctor bills.

“Project Success is just ridiculous in Arkansas because the assistance payments are so low women can’t afford to stay in the program,” says Brownie Ledbetter, executive director of Arkansas Career Resources, a non-profit organization that works with welfare recipients. “Then there’s no follow-up on the women who manage to get jobs, and nine times out of ten she’s eventually back on welfare. We’re recycling just like always.”

In order to qualify for AFDC payments in Arkansas, an individual’s income can be no higher than 29 percent of the 1985 U.S. poverty level. The low income necessary for participation is matched by the meager levels of support qualified families then receive. A family of three, for example, can count on only $351 in AFDC and food stamp payments each month.

“We’ve tried to get the governor to at least raise the qualifying standards to 1990 poverty levels, but he just won’t do it,” Ledbetter says. “He’s very active in the National Governor’s Association, but we can’t get him to raise benefits right here in our own state.”

As chair of the Governor’s Association, Clinton helped draft the Family Support Act, basing much of the legislation on fledgling workfare programs already in place throughout Arkansas. Project Success made Arkansas one of the first states to meet federal guidelines when it began on July 1, 1989.

Although Clinton has been reluctant to raise welfare payments, he was more than willing to expand the number of women forced to participate in Project Success. While previous workfare programs were mandatory for AFDC applicants with children at least six years old, Project Success included all women with children over one.

“The Family Support Act is very flexible — we could have had the minimum child age be three years old,” Ledbetter says. “But instead, we jumped right in as deep as we could go. What you get is very little progress because it’s spread so thin.”

Kenny Whitlock, who oversees Project Success as deputy director of economic and medical services for DHHS, believes the state can’t afford to limit participation.

“It’s true if we targeted fewer cases we could spend more money on the client,” he says. “But then we couldn’t help as many people. We know this approach is the only approach we can take. This is a real opportunity for people.”

“A Lot of Pride”

Janet Hayden’s first opportunity came in the mail. Unable to read or write, the 38-year-old mother of one had a friend read her the form letter from Project Success.

It stated she was required to attend an employment training session in Fordyce or risk losing the $329 she received each month in welfare benefits. Hayden went to the four-day session out of fear, but she laughs when asked about what she learned.

“They talked about how you go about getting a job, about dressing up and having confidence,” she says, standing on the front porch of a small house she shares with five other people in a predominantly black section of Fordyce. “To tell you the truth, I didn’t learn much.”

Asked about the assessment process required by DHHS to familiarize participants with Project Success and evaluate their educational standing, Hayden confirmed it never took place. She hasn’t heard from Project Success since she attended the training session last year.

Even when participants manage to get an assessment, critics argue it seldom produces a realistic profile of the educational or financial barriers women face. Project Success caseworkers, for example, may ignore a participant’s shaky relationship with a landlord because they can’t do anything about it. But when the rent is unexpectedly hiked or an eviction notice arrives, the woman may be unable to attend training sessions.

“Our fear in the very beginning was that the assessment process wasn’t truly comprehensive,” says Amy Rossi, director of Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families. “Women’s lives need to be stabilized so once they start training something doesn’t come up to make their lives fall apart. A change of circumstance — a $10 raise in rent — can make or break these families real quick.”

With only one caseworker for every eight Project Success participants, the special barriers posed by rural poverty are often overlooked in the assessment process. Many women live without phones on roads that are often washed out in the spring and too muddy to travel in the winter. Rossi dealt with one welfare mother who could only afford to wash clothes once a month, while another had only a pair of her husband’s old work boots to wear.

“You have people who really don’t have adequate clothing to go anywhere people will see them,” Rossi says. “There’s a lot of pride in these people. They would work if they had some of the other little things that would enable them to work.”

Walking Alone

In rural Arkansas, where a visit to the nearest grocery store can easily translate into a 15-mile round trip, adequate transportation can be as difficult to find as a well-paying job.

“It’s just not reliable because very few counties have any sort of system for picking people up reasonably close to their homes,” Rossi says. “That’s not the woman’s fault. It’s the fault of the system that can’t respond.”

In a state where only three cities — Little Rock, Pine Bluff, and Fayetteville — have mass transit systems, it was obvious in the early stages of the program that an extensive transportation network would need to be established. A study by the University of Arkansas released in October 1989 — four months after Project Success was implemented — reported that only two percent of participants could rely on public transportation to get back and forth to their job or training. A full 64 percent didn’t own a car, and 36 percent didn’t have a valid driver’s license.

Things haven’t changed much since then. Reports released late last year by county planning groups set up by DHHS to study Project Success uniformly listed transportation as the major flaw in the program. The sole public transportation in rural Sevier County are three vans that only transport senior citizens. In Lincoln County, the report states, “there isn’t any way for people without private means to travel about the counties to conduct business or keep appointments.”

Faced with the threat of sanction, women often call on relatives or friends for transportation, but such arrangements are often unreliable at best. Sharon Clancy, a 20-year-old who is expecting her fourth child, borrows her mother’s car to make the 12-mile round trip from her home in Thornton to Fordyce for GED courses. She was also giving a neighbor a ride, but the other woman quit attending because she couldn’t pay Clancy $3 a week up front for gas. The neighbor is now being sanctioned.

Janet Smith, who is expecting her second child late this summer, couldn’t find a ride from her trailer in Fordyce to GED classes. She now walks to her classes that meet twice a week from six to nine p.m.

“I walk two miles, but it seems like five,” Smith says. “I love school, but I don’t like walking alone at night. Some of the neighborhoods are pretty bad.”

Governor Clinton has created a task force to look at the transportation problem, but state officials expect no quick fix. “Our problem is that we don’t have any organized public transportation,” says Kenny Whitlock, who oversees Project Success. “There’s no network where a person can go and just call a number to get a ride. That’s what we really need.”

No Help Wanted

While finding transportation is often impossible, the search for adequate child care can be equally daunting. The planning report for Green County details problems typical of many rural areas in the state. “Most of the day care facilities in Green County are at their capacity,” the report states. “No day care is available for evening or late-night shifts which would facilitate factory employment. There is limited after-school day care. We do not have but four day care centers or family homes that will take a state voucher.”

Carol Rasco of the governor’s office concedes that child care is a “barrier to successful implementation of the program,” but says that child care money mandated by federal legislation should reach the state this fall and help ease the problem.

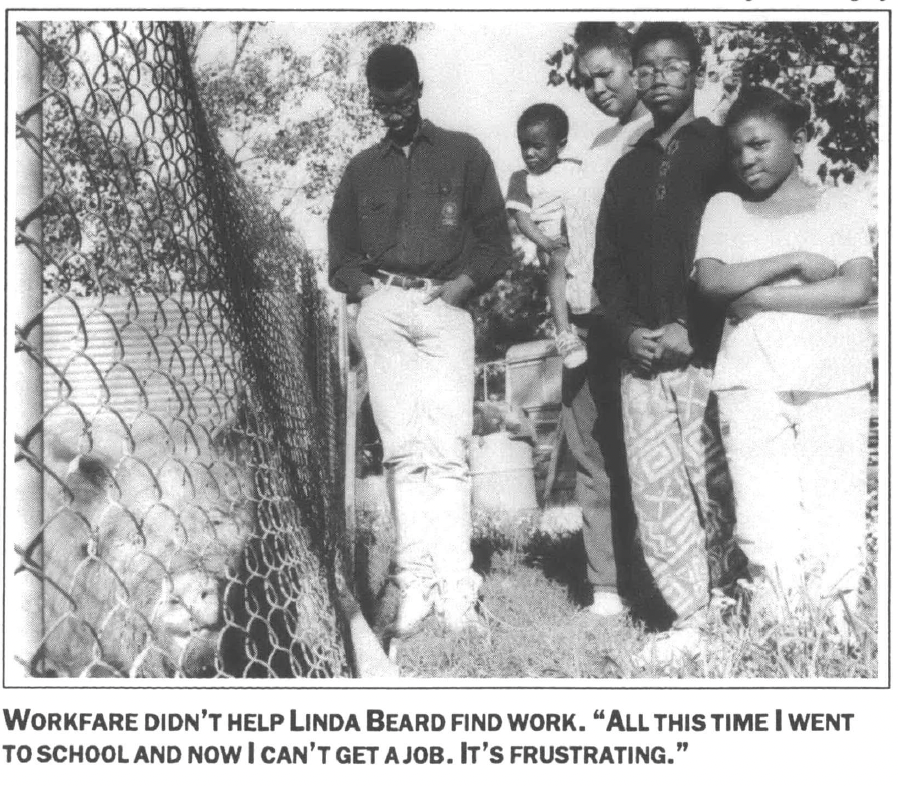

For the women who make it through job training or adult education classes, their perseverance often goes unrewarded. Linda Beard made the 40-mile round trip from her home in Grady to Pine Bluff for nearly a year to learn child care skills. Project Success originally provided transportation, but Beard eventually had to hitch a ride with a friend.

“If the weather was bad my road would get flooded and the van just wouldn’t show up,” Beard says, tapping her feet on the plywood boards covering the floor of her trailer. “Sometimes they’d call and tell me to ask around for a ride and sometimes they wouldn’t. Then it just stopped completely. I was wondering if I was ever going to finish because I’d go for awhile and then have to stop.”

Because of interruptions in transportation, it took Beard 12 months instead of nine to complete her training. She’s been job hunting in Lincoln County — with its unemployment rate of nearly 11 percent — since January.

“A lot of day care centers asked me when I would be finished and I had to tell them I didn’t know,” Beard says. “I went back later and they told me they needed me when they asked the first time. If I would have finished sooner I might have a job now.”

With only $704 in AFDC and food stamps coming in each month, Beard depends on a garden during summer months to feed her four children. The two hogs she bought at a local flea market and keeps penned up in a field near her trailer will eventually be slaughtered for food.

“There’s nothing I can do if I don’t find a job but just wait and pray,” Beard says. “All this time I went to school and now I can’t get a job. It’s frustrating.”

Without an extensive program to place participants in jobs once they’re trained, the frustration felt by Morgan is not unique. In addition to Lincoln County, Arkansas has 22 other counties with double-digit unemployment rates. Fourteen southeastern counties have an average unemployment rate of more than 11 percent, with Lee leading the state at 18.8 percent. Not surprisingly, the same 14 counties account for the most Project Success participants in Arkansas, with more than 4,500 open cases.

“A policy to find jobs for these people just isn’t there,” says Rossi, director of Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families. “It was missing in the beginning and it’s still missing.”

Karan Burnette, manager of the Project Success central office in Little Rock, adds, “There are some areas where there just isn’t anything there. You can train someone for a job, but there’s not always a job available.”

Reports issued by the Arkansas Division of Finance indicate that approximately 175 to 300 women find jobs through the program every month, but an average of more than 600 new cases are also opened.

And every month, the number of women sanctioned or “suspended” by the program outstrips the number who actually find jobs. Women are suspended when they can’t overcome “significant barriers” such as pregnancy or have completed necessary training but can’t find a job. Unlike women who are sanctioned, women on suspension still receive benefits.

“They developed the suspend category because they knew they couldn’t handle rural areas,” says Rossi, who served on a governor’s advisory committee for Project Success. “If you’re suspended you just sit and wait.”

During December of last year, for example, only 175 women in the program found jobs statewide — while sanctions claimed 190 women and suspension 973 more. Forty-four counties had more sanctions than jobs, and 22 counties produced no jobs at all.

$3.35 an Hour

Shoddy record keeping and haphazard tracking make it difficult to ascertain exactly what kind of jobs Project Success participants are finding. DHHS stopped compiling county records with detailed job descriptions or wage levels more than a year ago. A comprehensive, statewide study of jobs will not be available until a new computer is installed next year.

“About the only gauge of how people are doing is when they make enough money to get off public assistance,” says Whitlock, the project supervisor. “We used to file monthly reports with job descriptions and wages, but it took too much staff time.”

Critics of the program argue that judging Project Success solely by the number of jobs produced and money saved on AFDC payments ignores the hardship caused by placing women in low-paying, dead-end jobs.

“The tragedy is that numbers drive this program,” Ledbetter says. “Every overworked DHHS worker at the local level has to churn out X number of ‘successes.’ But the person who gets screwed is the client. They have such low expectations for these women — I swear to God they’re putting people in domestic work.”

For Terri Morgan, landing a job brought her no closer to financial independence. Like Janet Hayden, she attended one week of training in Fordyce designed to teach her the do’s and don’ts of getting a job. She says the classes provided little practical information, but she soon found work — making $3.35 an hour as a fry cook at a local cafe.

Despite inconsistent hours and weekly wages below $80, the state cut off the $204 in monthly AFDC payments Morgan was receiving to support her two sons.

Both boys were the product of incest when Morgan’s father raped her as a teenager. She is trying to get her father to help support the children, but she isn’t counting on it. She says she is scheduled to lose her Medicaid payments once a six-month “transitional period” ends — even though the Family Support Act provides for benefits up to one year unless health care is provided by the employer.

When asked what will happen if she or her sons get sick, Morgan replies, “Jesus, I don’t know. ”

For Jo Anne Cayce, who often gives food and clothing to families that have lost their benefits, Morgan’s story sounds all too familiar. “If the government is going to get them a little old job and then take everything away from them, what’s the point?” she asks. “People should be rewarded for finding a job, not punished.”

Tags

Gordon Young

Gordon Young is a reporter for Spectrum Weekly in Little Rock. (1991)