This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 2, "Punishing the Poor." Find more from that issue here.

Austin, Texas — Sheila Foscette has been on and off welfare for the past five years, and she’s seen it all.

She’s made repeated trips to the welfare office to look for work, only to be ignored by disrespectful caseworkers. She’s watched employment counselors conduct a “job search” by flipping through the Yellow Pages. She’s been forced to give up her health insurance and child care benefits to take a job that pays less than welfare. She even had to quit college because the state refused to continue benefits after she took 60 hours of classes.

“Once I was about to run out of food, I had no money, my case was screwed up,” Foscette recalls. “My caseworker wouldn’t even look at me. I said, ‘Please help me. My kids need to eat. I need money to go buy some sanitary napkins because it’s that time of month.’” The caseworker didn’t bat an eye. “That’s not my job,” he said, turning back to his keyboard.

The problem, Foscette concludes, is the bureaucracy. “It’s called the Department of Human Services,” she says, “but it has no humanity. They get out of touch.”

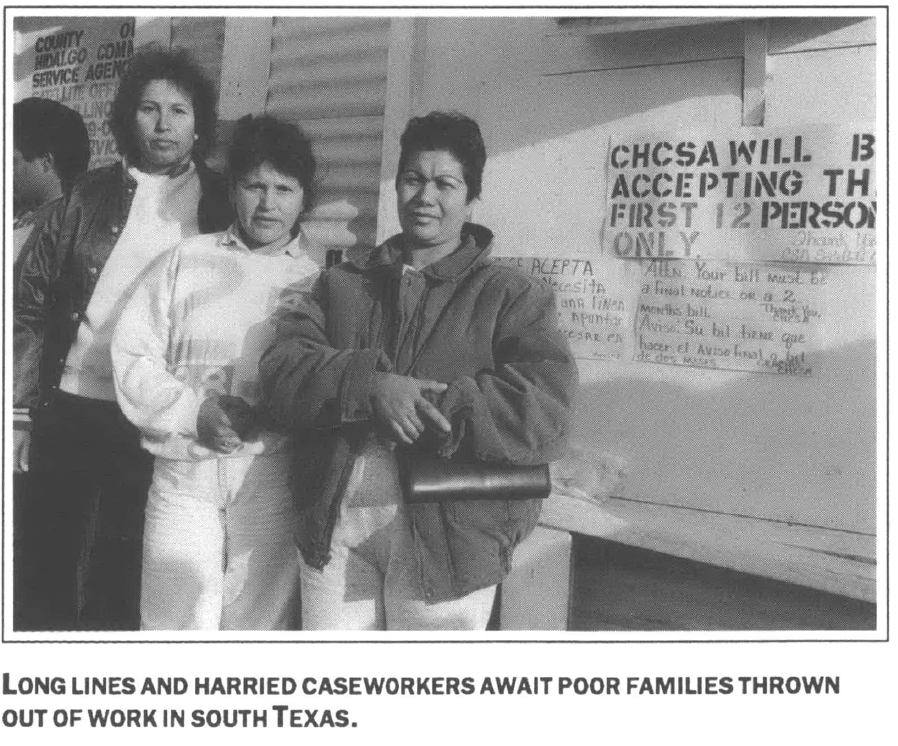

Sheila Foscette isn’t alone. Thousands of Texans on welfare have been ordered to find work or lose their benefits — and they have run headlong into a dizzying array of rules and regulations that make it virtually impossible for them to fill out a form, let alone find a job.

Texas, it seems, could be a case study in how not to run a welfare program. For years, the state made applicants for public aid fill out long, confusing forms that baffle even legal aid lawyers. Every applicant must list a permanent address — even though the wave of homelessness in the 1980s put thousands of Texans out on the streets.

The bureaucratic maze prevents many poor families from getting help. According to a report by the Southern Governor’s Association, Texas rejects a bigger share of welfare applicants than any other state in the nation. The state turns away half of everyone in need — three-quarters of them for “failure to comply with procedural requirements.”

In many cases, applicants are denied help because they can’t get a former landlord or ex-boss to fill out required forms detailing their housing and employment record. The result: an “Application Denied” stamp on their thick, carefully filled-out application form.

By enacting policies that so defy common sense, the state has created a tangled welfare system that does little to help the millions of Texans who live in poverty. The welfare bureaucracy has lost touch with the people it is supposed to serve. The story of what went wrong — and what the state could do to make amends — holds important lessons for the other Southern states.

Hard-Ass State

Texas has always been stingy when it comes to helping the poor. The state consistently ranks among the most miserly in the nation in providing for the welfare of its citizens. It provides Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) to only 840,000 of the 2.5 million people in need. The maximum benefit: $57 a month per person.

“Texas is paying people an AFDC grant that’s 32 percent of what’s deemed to be the need,” says Cascell Noble, advocacy coordinator at the Texas Legal Services Center. “And that standard of need is outmoded.”

Put simply, welfare checks have not kept up with inflation. Since 1969, AFDC benefits in Texas have lagged behind the cost of living by 23 percent, making it tougher than ever for families to get by.

This tight-fisted approach to public assistance can be traced in part to the Lone Star State’s frontier tradition of self-reliance. “It’s typical of Texan culture that we blame the person who has the problem,” says Debby Tucker of the Texas Council on Family Violence. “We say, ‘They wouldn’t be poor if they would just pull themselves up.’ We insulate ourselves from problems we don’t know how to solve by blaming the victim.”

The conservative state legislature has fueled the anti-welfare bias, imposing niggardly policies and niggling requirements. “The tone is set at the legislature,” says a former official with the Department of Human Services (DHS) who asked not to be identified. “We do not have liberal interpretations of federal programs. Look at AFDC — there’s only been one time in the 1980s in which the state elected to raise benefits. This has been a hard-ass state.”

The penny-pinching attitude has filtered down to the DHS, the state agency that administers welfare programs. “Historically, many people in the agency viewed its role primarily as protecting the taxpayers,” says Kelly Evans, an Austin legal aid attorney who represents AFDC recipients. “They deliberately put up barriers to participation to keep caseloads down, because the budget wouldn’t allow them to meet the needs of all those who really needed help.”

State workers who want to help clients discover they simply don’t have the time or resources to do the job. “Caseworkers in the field have enormous caseloads relative to other states, and there’s extreme pressure for accuracy,” says Dianne Stewart, a former DHS policy official. “The people who go into those jobs have good intentions and want to help people, but because they’re faced with an overwhelming workload and pressures, they can’t even devote time to thinking much about what the recipient’s circumstances and needs are.”

The staggering workloads force caseworkers to become little more than data-entry personnel. “It’s like you’re in there on an assembly line,” says Sheila Foscette. The average DHS caseworker handles 240 cases — far more than the legislature budgeted for — and the problem is getting worse. Last year, the number of welfare applications soared by 38 percent, and the average caseload jumped by 21.6 percent.

Penny Unwise

The placid atmosphere in the Austin welfare office belies the stress felt by both recipients and caseworkers. About two dozen people sit in the waiting room — mostly women, mostly Hispanic, mostly young. Some fill out application forms; others stare into space, waiting for their names to be called. A few potted plants add a touch of green to the antiseptic blue walls and fluorescent lighting. Though it’s a hot, early summer Texas day, the water fountains are broken.

Once those in the waiting room get in to see a caseworker, they will have to negotiate a maze of federal and state rules. “Front-line workers in DHS are basically penalized or rewarded based on how accurate the information is — not on how well they serve the client,” says Christopher King, a University of Texas professor who has studied the welfare agency.

King notes that the federal government penalizes the state each time a caseworker approves an ineligible applicant for welfare. The result: “The reward system is geared toward not screwing up. It’s much worse to be caught making a mistake than running a program that performs poorly. That gives you the wrong kind of character on the front lines.”

Miles to Go

Texans who live in poverty and their advocates are pressing for far-reaching changes to make the Department of Human Services more responsive to those it serves. Among the proposals:

▼ Break the agency up into smaller pieces. Advocates say that having several boards overseeing fewer programs would improve efficiency, accountability, and responsiveness. Newly elected Governor Ann Richards has already appointed three members experienced in human services to the DHS board, including its first disabled member.

▼ Eliminate punitive regulations. DHS must overhaul the “punish-the-poor” mentality that poisons the atmosphere of public assistance. “We have to put in place a system that rewards caseworkers on how well they get people off welfare,” says Chris King, a University of Texas professor who has studied the state welfare system.

▼ Provide more resources. Human services advocates are pushing Texas to adopt an income tax to finance investments in human resources. “It will cost $1.5 billion next biennium just to maintain our abysmally inadequate standards,” says Jude Filler of the Texas Alliance on Human Needs. More money is needed to train caseworkers, lighten caseloads, and provide meaningful job-training to those on welfare.

▼ Recruit and reward good caseworkers. Advocates say DHS needs to hire more minorities and former welfare recipients as caseworkers. “We need to pay them better and train them better,” declares Leslie Lanham of the Children’s Defense Fund. Workers on the front lines should also have more say in shaping policies.

▼ Place caseworkers in the community. Lanham and other advocates recommend decentralizing welfare offices. “Rather than having all the caseworkers in one building where they only see other DHS workers, put them in clinics, hospitals, and schools, where they see what happens to clients,” says Lanham. “Get them into areas where they can see a pregnant woman getting health care as a result of their work in getting them Medicaid. Get them out in the world where they can see clients as whole people.” Just recently, DHS took steps in this direction by opening offices in hospitals.

▼ Make home visits. Visiting clients at home would help caseworkers make better decisions. “White middle-class people don’t know what it’s like to live in a project,” insists Sylvia Meyer, a DHS supervisor. “Home visits would educate workers, give them a little more cultural sense and empathy — a little more tolerance. Then we could give a little power back to the clients by getting them more involved in their own cases.”

▼ Train clients for decent jobs. Job training programs should give welfare recipients a shot at a career instead of shunting them into low-wage, dead-end work. “I’d like to see more emphasis on policies that promote independence and dignity,” says Ilene Gray, a human services consultant who stresses the need for detailed, individual assessments with each client.

▼ Educate the public. To build political support for effective, responsive policies, advocates want to teach taxpayers about the realities of welfare. “A lot of people don’t understand what happens to people who are forced to the fringes of society,” says Debby Tucker of the Texas Council on Family Violence. “A lot of people are still stuck in the idea that it’s your own fault if you got in trouble. They don’t have a clue about what it’s like to grow up on streets and have to steal your own food.”

— B.C.

Such pressures help explain why nearly a third of all DHS caseworkers leave the agency every year. “You become a senior DHS worker if you last three years,” notes Debby Tucker of the Texas Council on Family Violence.

The pressures also help explain the hostility some caseworkers exhibit toward their clients. A DHS caseworker in San Antonio, for example, recently caused a stir with a letter to the local newspaper describing AFDC recipients as fat, unappreciative deadbeats who have children just to stay on welfare. “They have never worked a day in their life,” the caseworker wrote, “and don’t intend to if they can get away with it.”

Such hostility is fueled by the cultural gulf separating caseworkers from clients. “I’m a white, middle-class, single person,” says Sylvia Meyer, a social services supervisor at a Dallas DHS office. “I don’t know what it’s like to have raised three or four kids by the time you’re 33, like some of my clients have. I don’t know what it’s like to live from paycheck to paycheck.”

With caseworkers operating under tremendous pressure, welfare recipients never know what to expect when they contact DHS. “I’ve had caseworkers who were real sweet. During the interview, they asked me about why I’d got on welfare, they really cared about me,” recalls Sheila Foscette “And I’ve had caseworkers who just get you in there, ask you questions about your case, and that’s it — they show no emotions whatsoever.”

Confronted with indifference or outright hostility from the agency that is supposed to help them, many poor Texans never receive the services they’re entitled to. They consider the agency “an obstacle to their survival,” says Kelly Evans, the legal aid lawyer. “Remember, this is a clientele that’s dependent on buses. They have kids, and they may lose income when they take time off to get the documents they need. A lot of people just don’t come back. They drop out.”

Mushrooming Rules

With the Texas welfare system so bogged down in bureaucracy, it’s little wonder that workfare “reforms” mandated by Congress in 1988 only added to the mess. A decade ago, caseworkers in Texas administered four separate welfare programs. Today they must master the complexities of 30.

“There’s this bewildering avalanche of information pouring into the field, and not all of it gets disseminated quickly to the bottom,” says a former DHS official. “They’re too busy trying to cope with all these federal and state changes to concentrate on helping people. A lot of workers feel like they’re a part of the mushroom theory: keep ’em in the dark and throw a little shit on ’em every now and then.”

The sheer size of the welfare agency — it employs more than 15,000 people — contributes to the bureaucratic isolation. “When a system is really big like DHS, its goal becomes one of self-protection,” says Debby Tucker of the Texas Council on Family Violence. “That kind of hierarchical system increases paranoia and decreases creativity.”

Many inside the bureaucracy privately agree. “A lot of people who gravitate to state office tend to be rule-oriented,” says one DHS official. “They’re not the kind of people who start questioning whether the programs are actually helping anyone. They aren’t all that eager to re-examine rules and say, ‘How can we make this system open and accessible to those it serves?’ All bureaucracies have people like this, but welfare, because it is incredibly rule-driven, tends to have more than its fair share.”

For DHS bureaucrats who spend their work days confined to the agency’s state headquarters in Austin, the isolation is also physical. The gleaming DHS office building was completed in 1984 — at a cost of $26 million.

Cronies and Phonies

Despite the obstacles to change, the Texas welfare system looked like it might be on the road to reform a few years ago. In 1989, DHS got a board chair who said he was ready to question the rules. Rob Mosbacher Jr., a Houston socialite and scion of the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, vowed to shake up the inefficient agency.

He shook things up — but not entirely for the better. Although Mosbacher spouted the right rhetoric and initiated a few reforms, his appointments to top policymaking positions soon drew fire from all sides.

People on the inside complained that Mosbacher hired his friends to run things. “His political appointees knew little about running DHS, and they hired people like themselves who didn’t know how to do their jobs,” says Jude Filler, director of the Texas Alliance on Human Needs. “By the end of ’89, the people at the bottom were appalled by the incompetence at the top, and morale just plummeted.”

Mosbacher tried to fill one top administrative post with a political pal who had devoted his career to lumber. Advocates also accused Mosbacher of deliberately underestimating the surge in caseloads to avoid asking the legislature for more money during his campaign for lieutenant governor. Mosbacher lost the race — and DHS lost sorely needed funding.

The most fundamental change that shook the state welfare system in 1989 came not from the top, but from the ranks of the frustrated poor. A welfare recipient named Carolyn Lewis sued the state, charging DHS with systematically preventing her from receiving benefits.

The state settled the lawsuit in 1989, agreeing to demolish some of the procedural barriers confronting clients. According to Roger Gette, the lead attorney in the suit, DHS has condensed its bewildering 17-page application package to a simpler, four-page form. The settlement requires caseworkers to help clients fill out forms and obtain documentation — and to take the applicant’s word for it if they can’t produce the necessary paperwork.

What’s more, rejection letters to clients must now include a list of alternative procedures and programs the client can take to obtain aid. The presumption has changed, at least officially, from suspicion to trust.

The settlement is far from a cure-all. Gette complains that “some areas that were problems before the lawsuit are still problems now. We’ve seen grudging compliance at best.” But he concedes that the number of complaints to legal aid lawyers has dropped by 66 percent.

The same year that the state settled the Lewis suit, the “reforms” mandated by the Family Support Act also began to take effect. Unfortunately, the plan hatched in Washington didn’t make much of a dent in the Austin bureaucracy. The state agreed to end its long-term policy of forcing families to break up in order to qualify for AFDC — but true to its reputation as a miser, the legislature only provided six months of benefits, creating a bureaucratic nightmare for caseworkers and recipients alike.

Still, a few modest reforms have managed to creep into the system. DHS notices are now written in both English and Spanish. Caseworker training has been revamped to include a session on “people skills.” Computers are enabling some applicants to do “one-stop shopping” for all the forms they need, freeing up caseworkers to spend more time with clients. And the agency has set up local advisory policy review committees composed of recipients, front-line caseworkers, advocates, and policy planners to provide much-needed feedback to the central office.

Many of the changes were only implemented statewide last October, but welfare advocates say things seem to be improving — albeit slowly. “There are still some problems, but I think over the last two years there has been a concerted effort by the agency to try to change the image of the department,” says Kelly Evans, the Austin legal aid attorney.

But with the number of welfare cases expected to triple over the next few years, most Texans trapped in the system don’t hold out much hope for change. The only real difference, says welfare recipient Sheila Foscette is that caseworkers now push single parents into “McDonald’s jobs” that pay even less than welfare.

“Why should you have training as a nurse and go be a garbage woman?” says Foscette, who completed two years of college. “Why should you give up your dream?”

The welfare bureaucracy will remain out of touch, she insists, until the bureaucrats come out from behind their desks.

“The only way they’re going to get in touch with the people is if they take off their nice suits and dresses, put on some blue jeans, take the bus to the welfare office, go through an appointment, fill out an application, and pretend they don’t have any money in their pockets,” Foscette says. “Then they will understand.”

Tags

Brett Campbell

Brett Campbell is managing editor of The Texas Observer. (1991)