This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 2, "Punishing the Poor." Find more from that issue here.

Wayne Stutler has tracked down killers and extortionists over his 32 years on the police force in Fairmont, West Virginia, but he says he’s never been so stymied in “finding justice” as in the case just down the hill from his home.

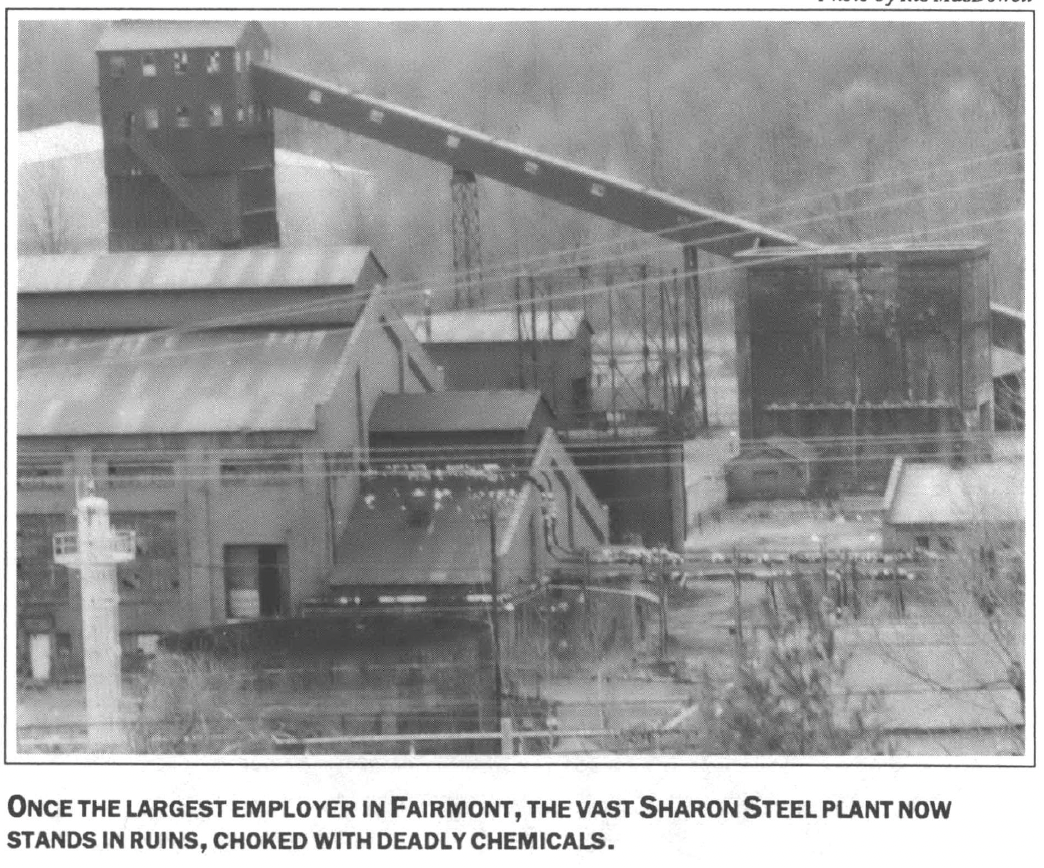

He walks across his lawn to the edge of Hoult Road. In the valley below, he points to the ruins of row after row of coke ovens, flanked by railroad trestles, an ammonia plant, cooling towers, and a coal tipple stripped of its machinery and rotting in disuse.

Amid this jumble of derelict equipment, which runs for half a mile to the banks of the Monongahela River, are 120,000 cubic yards of hazardous waste, the outgrowth of years of dumping coal tars, cyanides, ammonia, arsenic, beryllium, phenol, and acids at the vast Sharon Steel coke plant.

The chemicals have leached into the soil, befouling underground springs. After a rainstorm, uncontrolled surface runoff dumps the wastes into backyards and chokes local creeks, which rise and carry the contaminants into the Monongahela.

Behind this mess lies a web of alleged coverups, regulatory lethargy, and the veiled world of the plant’s former owner — corporate raider Victor Posner.

“We call it rape and run,” says Stutler, Fairmont’s retired police chief. Like other residents, he believes that Posner took advantage of the Monongahela Valley, where natural beauty seems to be rivaled only by industry’s relentless drive to plunder its natural resources.

“When Posner was running the ovens, we couldn’t attract industry to the city because the plant was so far in excess of air pollution standards,” remarks Rosemary Ruben, who formed Citizens Holding Onto a Klean Environment (CHOKE) to fight the pollution. “Now we can’t attract industry because no company wants to be near a hazardous waste dump. The guy took the money and never reinvested it.”

Posner is a legend on Wall Street: a master in the art of paper finance and leveraged buyouts. A seventh-grade dropout who turned 72 last September, he runs his financial empire out of Miami Beach, where he can indulge his passion for dealmaking, limousines, jumbo-sized estates (he owns seven houses and condominiums) and teenage girlfriends.

He puts his children and relatives on the payroll of the companies he buys. Big salaries and even bigger bonuses follow in the wake of a Posner takeover. Although three of his entities have collapsed into bankruptcy, sagging under heavy debt, the financier remains one of America’s richest men. He has salted away $300 million, perhaps more, in stocks, real estate, and a family trust. No matter what happens to his companies, he is fond of saying to his associates, “it’s not going to change my lifestyle.”

Posner has been in the news in recent years, pleading guilty to tax evasion and charged with stock reporting violations by the Securities and Exchange Commission. His alleged transgressions against stockholders, however, pale in comparison to his dirty deeds in Fairmont. Far from the media spotlight, in northern West Virginia, Posner dismantled a vital factory, threw hundreds of workers out of good jobs, and polluted the soil, air, and water.

The economic and environmental destruction is a reminder that the debris from a decade of financial excess has not been confined to Mike Milken’s X-shaped trading desk or Ivan Boesky’ s suitcases full of cash, but has spilled over to heartland communities like Fairmont. Posner was one of the first financial pioneers to discover he could get rich by piling up “junk bond” debts on Wall Street — and then ransack Main Street to stay one step ahead of his creditors.

Victor Posner entered the life of Fairmont in 1969, when he staged a hostile takeover of the Sharon Steel Corporation. A real estate developer in Florida and Maryland, Posner was a new breed in the world of high finance — a self-styled “conglomerateur.” He was not interested in mining coal or making steel; he was a numbers man who scoured for “undervalued situations” in corporate America — companies he considered “underpriced, with good cash position and no debt.”

He began his corporate raiding with DWG, a Detroit maker of cigars and pipe tobacco. When a management feud broke out, Posner entered the fray and emerged as chairman and CEO. He then shed the cigar business and used DWG to buy interests in National Propane, Southeastern Public Service Company, and Wilson Brothers. Although the companies sold very different products — liquified gas, underground cable conduits, and men’s shirts — they soon had one thing in common: Victor Posner, who made himself the boss.

At the same time, Posner was eager to transform his small laminated plastics company named NVF into a conglomerate. Although the company wasn’t doing too well in its own business, NVF was the vehicle that Posner used to acquire Sharon Steel.

Posner lured Sharon stockholders by offering to swap their shares in the company for NVF bonds with a face value of $70 — 40 percent above what Sharon stock was selling for on the New York Stock Exchange. For Posner, the key to the deal was that he didn’t have to pay off the $99 million bill for the takeover until 1994, when the bonds came due. The takeover was not only an early instance of a little company gobbling up a big one (Sharon was seven times NVF’s size), but of equity (Sharon stocks) being swapped for debt (NVF bonds) in a hostile takeover.

A Dirty Business

Fairmont is not the only place where a Posner-controlled company has been embroiled in environmental disputes. Here’s a partial list of other recent cases:

▼ Graniteville Co. last year entered a consent decree with the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control after the agency found contamination in Langley Pond. The textile maker, required to submit a report on the pollution, recommended that pond sediments be left undisturbed. The agency has responded by requesting additional information, but a local citizens group is fighting to make the company clean up its toxic wastes.

▼ Last November, the Florida Department of Environmental Regulation notified a unit of DWG that waste water discharges at its citrus processing plant in Auburndale were “acutely toxic.” The company responded by claiming “the absence of any continuation of any such alleged discharge.” If convicted, the company is subject to a $10,000 fine and criminal penalties.

▼ Sharon Steel paid a record $500,000 penalty last year to settle pollution suits dating back to the mid-1980s by the EPA and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources.

▼ Earlier, the steel company was accused of lying about toxic waste discharges at its works in Pennsylvania, leading EPA official Maureen Brennan to urge the federal government to cease buying steel from Sharon because of its flagrant disregard for the Clean Water Act.

▼ Posner’s NVF has allegedly dumped PCBs in a creek and landfill near Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, spawning several long-running battles with state and federal officials. Delaware authorities have also asked for civil penalties against NVF for allegedly dumping oil discharge into White Clay Creek.

▼ NVF paid $150,000 under the EPA’s “Superfund” program to clean up wastes the company buried in a landfill in New Jersey, and faces potential liability for environmental contamination at another site in Elkton, Maryland.

▼ The EPA filed suit in U.S. District Court in Cleveland accusing Sharon Steel of discharging pollutants at its Brainard, Ohio division throughout the 1970s and 1980s without applying for a federal permit. The company recently agreed to pay $175,000 to settle the complaint.

— M.R.

The Sharon deal made a tremendous impact on Wall Street, serving as a forerunner to the junk-bond and leveraged-buyout boom of the 1980s. In Fairmont, where the Sharon coke plant was the biggest employer in town, the conquest was greeted with astonishment. Posner had no track record in West Virginia — but given the state’s history, people should have been wary.

Fairmont owes its gritty industrial character and extremes of wealth and poverty to coal. From the narrow, winding valley of Buffalo Creek east to the Maryland border, and from the Pennsylvania line south to Buckhannon and Elkins, the hills are honeycombed with seams of “high-volatile, Pittsburgh coal,” excellent for iron smelting and other industrial uses. Mining began here in the 1850s, and the importance of the enterprise was reflected in the fact that the founders of Consolidation Coal, the Watsons, built their opulent estates, High Gate and La Grange, on the outskirts of town.

On the heels of coal came oil. The rich beds of oil and natural gas in neighboring Mannington attracted other moguls, including Standard Oil tycoon and former U.S. Senator Johnson Newlon Camden. Camden built a railroad line between Fairmont and Clarksburg, using the Watsons as his agents to buy 70,000 acres of prime coal and gas land at prices as low as $5 an acre. He organized the mines at Monogah with future Governor Aretus Fleming and cleared virgin timber from central West Virginia.

Clarence Wayland Watson dazzled Wall Street in 1909 by merging the coal fields of Somerset, Pennsylvania and the Fairmont mines into Consolidation Coal, the biggest coal trust in the nation. The company was invigorated with $20 million in fresh capital, much of it supplied by John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil.

In 1920 the Rockefeller-Camden- Watson interests unified their West Virginia coking facilities into Domestic Coke Corp. and established a large byproduct plant in East Fairmont. Sharon Steel purchased the plant, plus a coal reserve of 15 million tons, in 1948.

For the next 20 years, the plant and the Joanne mine at Rachel supplied coking coal for the blast furnaces in Sharon, Pennsylvania. The sprawling factory also sold sulphate, benzol, and other coal chemicals used to manufacture women’s nylons, explosives, aspirin, plastics, and highway asphalt.

Like the moguls of old, Posner placed coal at the center of his strategy as chairman and CEO of Sharon. To raise cash, he sold the Joanne mine to Eastern Associated Coal and entered into a contract with Eastern for the long-term supply of coal. Thus assured of a low-cost source of raw material, he shut down Sharon’s coke ovens in Templeton, Pennsylvania and began selling its mined coal to outsiders.

Fortune smiled when the energy crisis induced by the oil embargo gripped the nation in 1973. Spot coal prices soared from $8.50 to as much as $80 a ton in a little over a year. By buying coal cheap and selling it dear, Posner reaped windfall profits. In 1976, nearly half of Sharon’s operating profits came from its coal operations, which amounted to less than 10 percent of sales.

Posner used these profits to underwrite his increasingly ornate lifestyle. A corporate jet, 100-foot yachts, speedboats, a penthouse suite at the Plaza Hotel in New York — all were furnished for his comfort by his captive companies. Sharon, a landlocked Pennsylvania company, saw fit to purchase three company yachts. The least of them cost $190,000, while the most expensive was $1.5 million. Each was conveniently docked at the chairman’s house on Sunset Island, Miami Beach.

A 1978 audit ordered by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) found that Posner billed his companies for the rent on his 10-room Plaza suite, Cigarette speedboats costing $94,000, chauffeured Mercedes on around-the-clock call in New York and Miami, $100,000 for personal air travel, a cabana at the Fontainebleau Hotel, and liquor and restaurant bills in excess of $100,000.

His children also lived well at company expense. On Manhattan’s East Side, Gail Posner had her own limousine and driver, the use of Sharon’s corporate jet, charter helicopters, and $39,032 in free telephone calls. The cost of Steven Posner’s Plaza suite was picked up by his dad’s firms, along with a beach house in the Hamptons, a vacation spot in the Catskills, a Stutz, and free groceries.

To settle the SEC complaint, Posner and his children agreed to repay nearly $2 million to his companies — but not without a lot of personal angst. At one point Steven protested to an SEC lawyer that it was unfair to ask him to pay for his $6,400-a-month rooms at the Plaza because he and his family had been subjected to “jungle-style tenement living” there.

The lawyer was startled. “The jungle tenement living that you are referring to — was that at the Plaza Hotel?”

“Yes,” Steven answered. “This is the way the family and I viewed it.”

Far from Steven’s sufferings at the Plaza, Wayne Stutler knew something was wrong when the coke oven doors kept “blowing out” at the Fairmont plant.

“It was terrible,” he remembers. “The explosions waked you up at night. Sometimes you’d think the place was blowing up.”

From Coal to Cola

Gulp down an RC Cola or chomp through an Arby’s roast beef sandwich and you’ve added pennies to the Posner realm.

After piling up disastrous losses as an industrialist, Victor Posner has moved into the consumer world, becoming a fast food and soft drink tycoon, with a sideline in leisure wear.

Three companies based in Georgia and South Carolina now form the heart of his shrinking empire: Royal Crown Cola, makers of RC, Nehi, Diet Rite, and Upper 10 soft drink concentrates; Arby’s, Inc., the nation’s largest roast beef franchise, with 2,100 restaurants, and Graniteville, a textile maker specializing in cotton-polyester leisure and sports wear.

For the most part, these companies were purchased courtesy of about $250 million in “junk bonds” sold through Posner’s former friend Michael Milken of Drexel Burnham Lambert. In the case of Graniteville, the former owners terminated the pension plan, purchased annuities for the employees, and used the $36 million surplus to help Posner pay for the acquisition.

Controversy dogs Posner in his latest ventures. “We’re builders, not liquidators,” he pledged shortly after buying Graniteville. He then padlocked several mills, dismissed employees, and even lopped off police and garbage service in Graniteville, South Carolina, one of the country’s last company towns.

Last year Posner became embroiled in a battle with Arby’s franchisees after Leonard Roberts, the head of the unit, resigned in a public spat with the raider. According to Roberts, Posner siphoned money from the chain via unjustified management fees and refused to make capital improvements — moves right out of his Fairmont, West Virginia play book.

“He has no feel for a business. He only looks at the numbers,” says Roberts, now chairman of Shoney’s. In a court hearing in Cleveland, Roberts gave an unprecedented account of the inner workings of the Posner domain, which is housed in the former Victorian Plaza Hotel in Miami Beach, where the short, frail-looking powerbroker runs his companies surrounded by security cameras and his ever-present bodyguards.

“Let me tell you, your honor, there is a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde situation here,” Roberts testified. When a DWG director once suggested that a statement dictated by Posner might be a bit exaggerated, the financier erupted into “a vicious personal attack on that individual,” Roberts said, with “language like, ‘you goddamn mother fucking son of a bitch, you never question me. I’m sick of this shitting loyalty. You are a piece of shit now, you were a piece of shit before I put you here, and you are still a piece of shit. I control this goddamn place.’”

Roberts also quoted Posner’s philosophy of life as expressed in his Miami Beach bunker and over Scotch at Tiberio’s, his favorite hangout in neighboring Bal Harbour. “That lecture [was that] these are all small people, and small people don’t survive, or get squashed by people with power and wealth, and he has all the power and wealth in the world.”

Posner also has an image problem. He avoided jail in 1988 for federal tax evasion when he agreed to establish a $3 million program for the homeless. The “Victor Posner Homeless Project” has since become the centerpiece of his campaign in Miami to shine up his image and reposition himself as a philanthropist and do-gooder.

But as with other masters of the universe, a time bomb ticks away in Posner’s kingdom. More than $265 million in junk bond bills will come due between 1996 and 1999. How will the debt be paid? With more firings? With more companies exploding into bankruptcy? With Posner already showing signs of Donald Trump wobbliness, his reign as a leisure wear and fast food baron may be brief.

— M.R.

For Rosemary Ruben, who lived a few doors down Hoult Road, it was the constant downpour of soot. “Everybody was getting sick. People were getting skin rashes. And I had trouble breathing. I went through all the allergy tests and the doctors couldn’t find anything. Then I started asking, ‘Do you think this could be related to Sharon Steel?’”

Residents woke up to find grit on their windows, on their cars, on grass, plants, everything. The rotten-egg smell of hydrogen sulfide increased. Loathsome pools of bluish-black liquid puddled in the breeze washout piles and drained into the yards of houses huddled, coal-country style, within 200 feet of the works.

“When you grow up here, you accept pollution, but this was something worse than in the past,” Ruben remembers.

“Then we started hearing about coverups,” Stutler adds. “That made me very angry.”

In Charleston, state environmental officials also heard about strange goings on in Fairmont. On a routine patrol of the Monongahela, an inspector for the water resources department reported “bubbling action within the river approximately 20 feet from the shore line.”

He noticed a pipe running along the shore line. He followed it and it led to the Sharon coke ovens. Another pipe was discovered in a cave. “This is willful pollution by concealed discharges,” the inspector wrote.

The plant was so broken down, an April 1978 inspection by the state Air Pollution Control Commission noted, that a foot-wide crack stretched diagonally across one coke oven battery. Several ovens were beginning to lean over and some had collapsed within, allowing poisonous gas to escape.

Three workmen suffered heart attacks while working on the ovens, and others complained of short breath and dizziness from the smoke and gas, according to Kenny Springer, president of the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers local at the plant. “Nothing was being kept up,” says Springer, a man with a weather-beaten face and slow drawl. “Say an oven needed to be relined. That takes six to eight weeks to do right. But they’d be throwin’ in bricks and gettin’ it fired again as fast as they could.”

The debt Posner had accumulated to purchase the plant impelled him to squeeze every dollar he could out of the operation. “We weren’t making a good product anymore,” a supervisor with more than 30 years seniority says. “Our tar got so bad that Reilly Chemical, a big buyer, couldn’t use it.”

Tests by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) showed that some coke oven workers were exposed to nine times the maximum daily dose of carcinogens. In December 1978, the agency cited Sharon for exposing workers to dangerous emissions, failing to provide safety equipment, and failing to regularly inspect and maintain the ovens.

In a news release, Posner scoffed at the OSHA inspection as “pie in the sky,” but Sharon eventually paid $10,000 in fines. (In keeping with his long policy of “no comment” to the press, the financier refused to be interviewed or to answer written questions about Sharon submitted to publicist Chuck Nolan.)

The state also cited the plant for massive violations of air pollution laws, but delayed taking action. Posner was promising to rebuild the plant — and state officials believed him.

“Victor Posner strung out the state of West Virginia,” charges Charles Beard, who was director of the Air Pollution Control Commission. “His people told us, ‘We’re going to build a completely modem coke oven battery. Spend $20 to $25 million. Just give us more time.’”

The Miami Beach mogul did not directly communicate with state officials, but used his brother Bernard and other Sharon officials as go-betweens. One time Bernard, known as Bob, jetted into Charleston to attend a meeting with the air pollution staff.

“I won’t forget it,” says Robert Weser, a member of the staff. “When we have compliance hearings, company officials tend to dress and act very formal. But Bob Posner comes in wearing a shirt unbuttoned to his navel, with a gold chain and gold bands around his arm.” Posner sat through the meeting, saying very little, Weser says. “The impression I had was they could care less what happened to Fairmont. They acted very cocky.”

Sharon shut down the Fairmont coke works on May 31, 1979. Two hundred people lost their jobs, and miners at Joanne were idled by the simultaneous shutdown of the old Sharon mine.

The village of Rachel became a virtual ghost town. Sumac and saplings sprouted at the mine head and soon reclaimed the B&O branch line that wound down Buffalo Creek to the city.

To this day, many people in Fairmont mistakenly believe that “the environmentalists” and “the government” were responsible for the closing. In fact, papers filed in Clarksburg show that the plant was shut the very day its low-cost supply contract with Eastern Associated expired. State and federal officials had granted Sharon permission to operate the ovens until “on or before June 30, 1979,” thereby enabling Posner to wring out the last drop of profit before his contract ended.

Sharon officials pleaded poverty, saying the company couldn’t afford new coke ovens that met environmental regulations. Posner, meanwhile, was waging another lucrative war on Wall Street. This time his target was UV Industries, a precious metals and coal company with mines in Alaska and the Southwest.

Hoping to elude the raider, UV stockholders had voted to liquidate rather than be acquired by Sharon Steel. Under the liquidation plan, Posner could have sold Sharon’s 3.4 million shares in UV for about $110 million in cash — plenty to build new ovens at Fairmont and undertake other needed improvements.

Instead, he bid for UV. “Victor is convinced that everyone who fights him is trying to cheat him,” observes a former associate, and he wanted to teach Martin Horwitz, UV chairman, a lesson for “cheating” him.

The raider did not propose to pay for UV out of his own pocket. That would be foolish. He arranged for Sharon Steel to float $411 million of subordinated debentures — better known as “junk bonds” — to cover the takeover. But to consummate the deal, he still needed to win SEC approval for registration of the bonds. In January 1980, the commission staff launched an investigation of alleged insider trading at Sharon Steel.

A month later, the Environmental Protection Agency moved against Sharon, filing suit in U.S. District Court in Clarksburg for air and water pollution violations at the Fairmont works. The agency sought $16.5 million in civil penalties for disregard of the Clean Air Act during 1978 and 1979, and $379,000 for the illegal discharge of water pollutants.

Within months, however, the two federal agencies backed off. Despite a critical report by the SEC staff of “suspect trades” among Posner companies, the commission brought no formal charges. As a result, the UV bonds were floated and Posner won control of the company in late 1980.

Then, in June 1981, the EPA dropped all proposed fines against Sharon. In return, the company pledged to build a $2.5 million facility to contain wastes at the Fairmont plant. The change in heart came just five months after President Reagan took office and named Anne Burford as chief of the EPA.

“We had a total reorganization and shifting of staff and orientation,” acknowledges Ray George of the EPA office in West Virginia. Under Reagan, the agency decided to allow Sharon to bury the wastes in Fairmont rather than remove them. “The cost would have been inordinate, and there was the question of public exposure to the material during transport,” says George. “It was done for the best of reasons.”

The “best of reasons” left the people of Fairmont facing the prospect that the city’s largest parcel of land — nearly 100 acres — would become a permanent waste dump. Under the consent agreement, a single clay-lined vault would be built for the disposal of wastes near the river, and a betonite slurry cutoff wall with “impervious cover” would surround oxidation pond #2, “which will also contain excavated sludge from pool #1, the redeposited sludge, light oil area wastes, and tar pit wastes.”

“It was a mockery,” says Rosemary Ruben. A nurse and mother, Ruben formed CHOKE with other residents to fight the consent decree. “At first I got phone threats to my life,” she recalls. “People said, ‘Who are you to stop jobs?’ The company was promising to reopen the plant and the workers thought they’d get their jobs back. It was a lie, but even my late husband said I shouldn’t get involved.”

CHOKE sold t-shirts, held a benefit dinner in Morgantown, and raised over $600. An engineer hired by the group found serious flaws with the containment plan. The “impervious cover” would crack over time, he stated, and a single-lined vault was not adequate to hold the landfill wastes. (“A double-lined clay vault would be the way it would be done today,” concedes Ray George of the EPA.)

At the same time, a study by Battelle Laboratories found that the dump contained higher levels of cyanide, phenol, and arsenic contamination than originally believed. And even the EPA faulted Sharon for continuing to dump wastes surreptitiously into the Monongahela River.

Frustrated by the lack of state and federal protection, the city decided to defend itself. In 1983, City Council passed an ordinance making it illegal to dump hazardous waste within city limits. “The Council decided that they didn’t want Posner’s pigsty in our parlor,” says George Higinbotham, then city attorney.

Sharon immediately filed suit to block the ordinance. Over the next three years the case ground through the courts. Although the company lost nearly every action it brought, attorney Blair McMillin bluntly told the Charleston Gazette that fighting the city in court would cost the company five to 10 times less than obeying the ordinance.

“Posner’s initial strategy was to pose such an aggressive threat to EPA that they backed off,” Higinbotham says. “Then when Fairmont took up the fight, the strategy was to wear us out.” Sharon found an unlikely ally: the West Virginia attorney general. In a brief filed with the state Supreme Court in 1985, the state’s chief prosecutor accused Fairmont of trying “to obstruct the exercise of state power” by passing a law that preempted the state’s Hazardous Waste Management Act.

The court rejected the state’s argument and validated the Fairmont law. McMillin then took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. By the time the high court rejected the appeal without comment, many more months had lapsed.

By the start of 1987, Wayne Stutler believed the company was finally going to comply with the law. The appeal process had been exhausted, and in his capacity as chief of police, Stutler had served a warrant on the plant guard, stating that Sharon was in violation of the city ordinance and subject to fines of $500 a day.

But he and other Fairmont officials couldn’t have anticipated what happened next: Sharon Steel filed for bankruptcy in April 1987. Sharon had defaulted on the UV bonds — the very debt Posner had floated to stage a hostile takeover while the Fairmont coke works were discarded. The company also suffered when Evans Products, another Posner operation, went broke. In all, the company was staggering under $350 million in debt.

In January 1988, Bankruptcy Judge Warren Bentz took the unusual step of removing Posner from control of Sharon for “gross mismanagement” and ordered a trustee to run the company. Last fall, Posner walked away from the wreckage of Sharon by agreeing to pay $7.5 million to settle legal actions brought by the trustee and creditors.

The settlement was a pittance to a man who made the cover of Business Week in 1986 as America’s highest paid executive. Court filings in Erie, Pennsylvania show that as Sharon lurched toward bankruptcy between 1984 and 1987, Posner reaped $12.7 million in salary and bonuses. Regardless of the disasters that befell his company or the citizens of Fairmont, the raider was not to be denied his cash by a board of directors composed of his brother Bob, his son Steven, his daughter Tracy, and other relatives and cronies.

The Sharon bankruptcy effectively stalled efforts to clean up the Fairmont wastes. Finally last October, the city won a small but significant victory when the company removed an estimated 5,000 cubic yards of deadly waste from the tar pits. According to a report by the Center for Hazardous Materials Research at the University of Pittsburgh, another 120,000 cubic yards of wastes remain.

City Manager Edwin Thorne says Fairmont is still waiting for post-Posner management to come up with a clean-up schedule for the remaining waste. The company emerged from bankruptcy late last year under the control of New York financier George Soros, whose Quantum Fund held a large block of the defaulted bonds.

According to Higinbotham, Sharon officials still assert that their only “responsibility” is to contain the waste on site. “If the EPA or West Virginia stepped in decisively, I’m convinced that the problem could be cured very quickly,” he says.

Despite the delays, citizens in Fairmont say they have learned a lesson about the value of community organizing. “I think our group and the city did accomplish something,” says Rosemary Ruben of CHOKE. “All the necessary laws to control toxic waste dumping are on the books.”

She and others hope their fight for local control of toxic waste dumps will have long-range benefits for West Virginia and other states plagued by industrial waste. But for now, they’re still worried about the mess Posner left in the Monongahela Valley.

Standing outside his home on Hoult Road, Stutler, a solidly built man with a deliberate manner of speaking, says, “I’d sure like this place cleaned up. It could be used for industrial or recreational purposes. The property has real potential. . . .”

Then he looks out at the ovens sprawling across the hills like gravestones in some gigantic and decaying cemetery, and shakes his head. Reality has returned.

Tags

Mark Reutter

Mark Reutter is an investigative reporter and the author of Sparrows Point: Making Steel — The Rise and Ruin of American Industrial Might (Summit Books). (1991)