This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 2, "Punishing the Poor." Find more from that issue here.

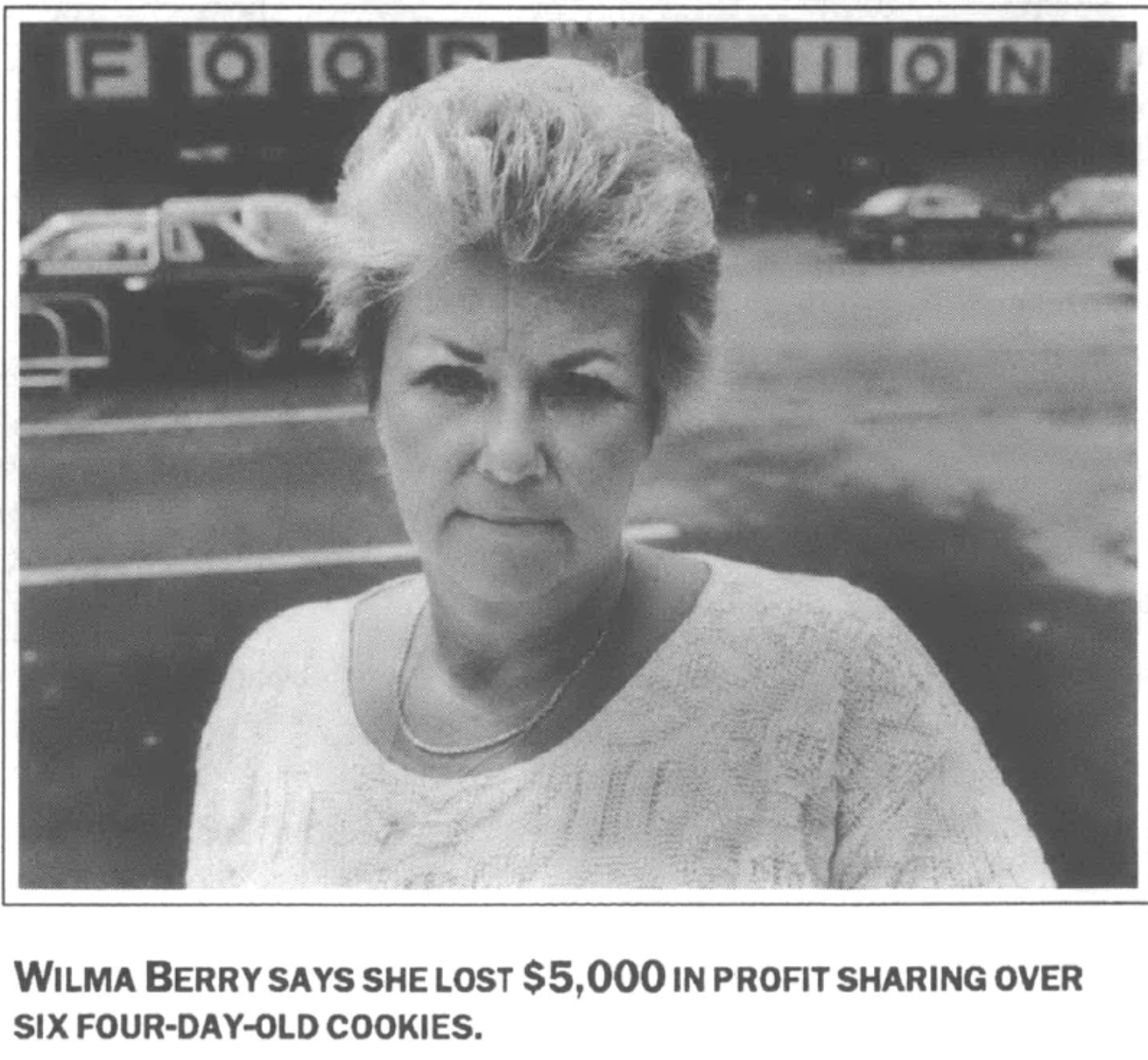

Knoxville, Tenn. — Wilma Berry loved to bake. She taught herself to make pastries and pies, and was proud of her skill in the kitchen. So when she was offered a job as a cake decorator at the local Food Lion supermarket, she was thrilled.

Berry worked hard and got high marks from her supervisors. One called her “very creative” and “trustworthy.” Each day before she left work, she collected outdated food from a throwaway pile and took it to Zion’s Children’s Home. “Later, when the orphanage closed, I brought food home and fed it to my goats,” she says.

One day last year, Berry took six four-day-old cookies and put them in a box to take home. As she was leaving, the store manager demanded to know what was in the box. “It’s throwaways,” Berry said. “No it isn’t,” the manager replied. “These items were supposed to be marked down. You’re suspended.”

Two days later, Berry got a call instructing her to meet with a Food Lion “loss prevention” agent. But when she arrived at the store, she found herself subjected to something the company calls “an interrogation.”

“They wouldn’t let my husband go into the room with me,” she recalls. “They locked the door. I told the man what happened, but he kept saying, ‘I don’t believe you. You’re lying. Everybody makes mistakes. All you have to do is admit it and you can go back to work.’ He threatened to have me arrested. After an hour and a half I began to cry. It was mental torture.”

After another hour of questioning, Berry signed a form saying she had taken baked goods “on three separate occasions.” To her surprise, Food Lion responded by canceling her health insurance and firing her for “gross misconduct” — but not before billing her $75 for the interrogation.

“I felt very humiliated,” Berry says. “I had heard about loss prevention, but I didn’t know how they worked. If somebody had told me that they had done people like that, I wouldn’t have believed it.”

More and more of Food Lion’s 50,000 employees are starting to believe it. Former workers in Tennessee, Virginia, and the Carolinas describe almost identical interrogations at the hands of company agents. What’s more, they say, the “internal police” are part of a general climate of insensitivity and intimidation that has helped make Food Lion the fastest growing supermarket chain in the nation.

“It’s a rough place to work,” says a former grocery manager in Tennessee who asked not to be identified. “Many days I would come home and sit down and cry. It was that bad.”

Share the Wealth

Food Lion denies such charges. “We want to get to the cause of a problem, but we want to do it in a legal and ethical way,” says Martin Whitt, supervisor of investigating coordination at company headquarters in Salisbury, North Carolina. “We’d rather let a lot of employee theft go on than accuse somebody who hasn’t done anything wrong.”

The company prides itself on its homegrown thriftiness. Tom Smith, who worked his way up from bagboy to president of the firm, appears on TV almost every night to demonstrate how Food Lion recycles cardboard boxes and turns off the lights to save money. “And when we save,” Smith grins at the conclusion of each commercial, “you save.”

The “extra low prices” the company advertises have exploded into extra large profits, making Food Lion the darling of Wall Street. Annual sales grew by an average of 25 percent during the 1980s to total $5.6 billion last year, and the number of stores soared from 141 to 778. Food Lion is now the third largest private employer in North Carolina. It has stores in 11 Southern states, and it is expanding rapidly in Florida and Texas.

But the experiences of many employees suggest that the Lion may be feeding on the misery of its workers. According to a lawsuit filed by a group of former employees supported by the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW), the company is illegally firing or pressuring workers to quit to prevent them from collecting profit-sharing benefits.

The profit-sharing plan serves as a sort of pension program. Employees earn a share of company profits each year, but they must stay with Food Lion for at least five years to collect the money. Wilma Berry was 18 months short of qualifying for $5,000 in profit sharing when she was fired.

Instead, Berry “forfeited” her earnings, and the money went back into a profit-sharing pool worth $317 million. The trouble is, few employees ever get to share that wealth. Company records filed with the Internal Revenue Service show that fewer than one in 10 Food Lion employees is entitled to full benefits under the plan.

What’s more, many of the forfeited profits wind up in the pockets of top Food Lion executives. According to the latest proxy statement filed by the company, Food Lion co-founder and chairman emeritus Ralph Kettner received $1,896,251.71 in profit sharing when he retired April 1. Because they share in forfeited benefits, many managers also make a direct profit every time an employee leaves the company before putting in five years.

Betty Deck says Food Lion hounded her into quitting seven months before she would have qualified for $35,000 in profit sharing. “The joke my supervisor always told was, ‘Every one of you that gets run off or quits, that’s more money we have to split among us,’” says Deck, who managed a Food Lion store in Gastonia, North Carolina.

Other ex-employees tell similar stories. “When you got close to collecting your profit sharing, they was looking for something to get you,” says Rusty Homaday, an assistant manager in Asheville, North Carolina who lost $59,000 in profit sharing when he was fired just 10 months short of being fully vested. “That’s a big chunk of change that went into someone else’s pocket.”

Grapes of Wrath

Food Lion blames the union for stirring up trouble. “You have to consider the sources of your information,” says company spokesperson Mike Mozingo. “It’s all part of a plan by the UFCW to discredit Food Lion. They are trying to paint a picture of a handful of cigar-smoking fat cats getting rich off people leaving the company. That’s totally false. There is no such scheme.”

The profit-sharing lawsuit is not the first time non-union Food Lion has found itself in court over unfair labor practices. This year, former employees Wayne Tew and Belinda Faye Lyle from Fayetteville, North Carolina sued the company for forcing them to work overtime on a regular basis without pay. Food Lion denied the charge, but on February 7 a federal judge ruled in favor of the workers and awarded them $53,352 in damages and back pay.

“This case hinges on a credibility determination,” the judge wrote in his decision. “The court did not find the testimony of the store managers to be credible.”

Food Lion also wound up in court last year after a company security guard stopped 61-year-old customer Charles Carrick at a store in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina and accused him of eating three grapes. Carrick sued, saying the guard grabbed him, called him a thief, took him into a back room, and refused to release him for 45 minutes until he paid nine cents for the grapes. A jury awarded Carrick $31,500 in damages for false imprisonment and slander — plus the nine cents he paid for the grapes.

Robert Willett paid a somewhat higher price when he was accused of nibbling grapes at Food Lion. An assistant store manager in North Myrtle Beach, Willett recalls working 14-hour shifts six days a week. “I can’t remember how many times I fell asleep at the wheel of the car driving home at 1:30 in the morning,” he says.

Willett says he was good at his job, but he wasn’t so good at managing his money. He remembers bouncing at least three personal checks at the store — mistakes he says he promptly made good. “It was a little bit my fault,” he admits. “I should have been more careful.”

The third time Willett bounced a check, a loss prevention agent showed up at the store. “I ain’t never been drilled like that in my life,” Willett recalls. “The man said, ‘Have you ever eaten a grape on the job? Had a banana at work? Gotten a coffee from the deli and never paid for it?’ I said everybody at the store has nibbled something at one time or another. He said, ‘A banana here, a grape there — maybe over a period of three years you’ve forgotten to pay for $1,000 worth of stuff.’”

Willett says he refused to pay for food he never took. After four hours of questioning, he says, the agent told him he would also be charged $320 for the interrogation. A week later, Willett was fired for “gross misconduct.” He lost $18,000 in profit-sharing benefits, and had to move his wife and four children into a smaller house.

“The loss prevention guys are really good,” he says. “They know exactly how to bully and intimidate you. They won’t ever let you see your accusers. Sure, I done that with the checks, and it was wrong. But it wasn’t about the checks. I honestly believe it was about the profit sharing.”

“The Perfect Crime”

A year after Willett lost his job, William Abrecht had a similar confrontation at a Food Lion warehouse in Elloree, South Carolina. One day last June, a loss prevention agent showed up and accused Abrecht of punching the time clock for his supervisor.

“They told me that if I wrote a statement saying that I knew what I did was wrong, I wouldn’t lose my job,” Abrecht says. “As soon as I wrote the statement, they fired me.” After four years on the job, Abrecht lost $20,000 in his profit-sharing account.

“The way loss prevention works is the perfect crime,” says Abrecht. “They say you won’t get fired if you put it down in writing, and then when you put it down in writing you can’t even collect unemployment because the company says you confessed.”

Mike Mozingo, the company spokesperson, says many employees fired by Food Lion have committed offenses that were more serious than they claim. For example, he says, the cookies Wilma Berry took from the Knoxville store weren’t four days old — they were gourmet cookies worth $5 a pound.

“That was not the only reason she was fired,” Mozingo adds. Asked to provide examples, he says: “There are other incidents with her that for her own privacy we’re not allowed to discuss.”

Still, isn’t it a bit harsh to fire workers for taking food without giving them a chance to change their ways? “If people are caught stealing, what would you suggest be done?” says Mozingo. “Food Lion loses millions of dollars every year on employee theft. There are warnings posted in the stores, and people know before they go to work that stealing will get you fired.”

Former employees say the tactics used by loss prevention agents are simply business as usual at Food Lion. Betty Deck, the Gastonia store manager, quit after she was questioned about pushing employees to work overtime without pay. She says she knows firsthand how managers treat workers, because she was one of the managers.

“Food Lion made me a bitch,” she says. “I didn’t want to be, but I had to be. They expected more out of you than any one person could deliver. I was working 100 hours a week. If I didn’t have an understanding husband, I’d be divorced right now.”

Deck and other managers say Food Lion relies on a system called “Effective Scheduling” that simply doesn’t give employees enough time to complete assigned tasks. Routinely forced to work overtime without pay to get the job done, many employees bum out.

“I’ve seen the company reports on turnover,” says Robert Willett, the assistant manager accused of munching grapes on the job. “It’s nothing for a store to go through 50 or 60 people a year. In most cases, that’s 100 percent turnover.”

“Food Lion just thinks of you as a number,” agrees Peter Carpenter, a grocery manager in Aberdeen, North Carolina who was fired for taking outdated food home to feed his father’s pet squirrels. “I think they get their kicks from getting rid of people. They treated us like nobody.”

Jeremy Barker was stocking groceries with Carpenter the night the loss prevention agents arrived. “They threatened us, said if we didn’t tell the truth they were going to take us to jail. They showed us the handcuffs they carried with them. I had never been threatened like that before. Here I was, 19 years old. It was only later that I come to find out we were talking to someone who didn’t have the right to threaten us like that.”

Presumed Guilty

Mention “loss prevention” to former Food Lion employees like Barker, and the reaction is apt to be one of terror. “We used to call them the Gestapo, because they think they run everything,” recalls Rusty Hornaday, who was interrogated about giving beer to under-aged employees. “You’d be working in the store at night, and you’d turn around and they’d be standing right behind you. That’s a spooky feeling.”

“They would raid your store and interrogate everyone,” adds Betty Deck, the Gastonia manager. “It was horrible feeling — you were guilty until proven innocent. I’ve never been treated like that before. They wore me down until there was nothing left. I felt like I had been raped.”

Martin Whitt, the loss prevention supervisor, says Food Lion agents only interrogate employees they know are guilty. “Once you get to the interrogation stage, you have your facts pretty much together. Every criminal has a rationalization; even murderers have an excuse. But that’s irrelevant once you get to the interrogation. You already know what happened.”

But former employees say this assumption of guilt made it impossible to defend themselves against false accusations. “If somebody’s got a grudge against you, they just call one of the hotline numbers posted in the store and say, ‘I saw this guy stealing’ — and boom! You’re out the door,” says a former manager who was fired last year for eating on the job.

Tammy Minnick was fired from her job as customer service manager at a Food Lion store in Bristol, Virginia after loss prevention agents accused her of forcing employees to work overtime without pay.

“They were very arrogant,” Minnick says. “They try to belittle you. They didn’t listen to anything you said — they knew it all. It didn’t matter what you said, you were guilty.”

Minnick says she eventually signed a confession, but not because she did anything wrong. “By the time they were finished with me, I didn’t know what I was admitting to,” she says, her voice breaking at the memory. “I was scared to death.” If she had been able to keep her job two more months, Minnick would have been eligible for $20,000 in profit-sharing benefits.

The $3 Thief

Delores Wilson, an executive secretary, used to work down the hall from the loss prevention department at Food Lion headquarters in Salisbury. One day, on her way to lunch, she found three one-dollar gift certificates lying on the floor.

“I put them in my pocket to give to the girl who handles them, and forget about them until I got home that night,” Wilson says. “I set them aside, and by the time I remembered them again I couldn’t find them. I assumed they got thrown away.”

They didn’t. Several months later Wilson was called in to the loss prevention department. Agents showed her three gift coupons bearing the names of her mother and two brothers.

“They said, ‘You stole these, didn’t you?’ I said, ‘No, I didn’t steal anything.’ They said I was lying and they were going to turn it over to the police. I said, ‘Fine — at least then I’ll be innocent until proven guilty.’”

That afternoon, Wilson says, her boss told her to clean out her desk and get out. “You’d think they’d realize it was just an innocent mistake. I told him, ‘Look, I don’t believe in stealing. It isn’t right, and I wasn’t brought up that way. And even if I was a thief, I wouldn’t waste my time on three one-dollar gift certificates.’”

Wilson and other employees fired by Food Lion also say the company violated federal law by failing to tell them that they were entitled to receive extended health insurance. As a result, Wilson lost her coverage. Today she works as a medical clerk at the veteran’s hospital in Rockwell, North Carolina.

“I like where I am now,” she says. “You’re not constantly in fear like you are at Food Lion. I’m the type of person who believes that what goes around, comes around. They’ll pay for what they did in the end.”

Wilma Berry says Food Lion agents still call her at home a year after she was fired, demanding that she pay the bill for her interrogation. Even worse, she says, friends and relatives still wonder why she signed a confession if she wasn’t guilty.

“My husband was a prisoner during World War II, and he said he can understand what I went through,” Berry says. “I feel so ashamed that I let them push me like that. Sometimes I wonder how these company people can lay down and sleep at night.”

Some former employees have taken comfort in joining with other workers to take the company to court. They want Food Lion to reinstate fired employees and appoint independent trustees to supervise the profit-sharing plan.

“There’s been a lot of people over the years that Food Lion has treated this way,” says William Abrecht, the former warehouse worker who is now a plaintiff in the suit. “At least I’ll have the satisfaction of having them answer for what they done. Maybe they won’t be able to treat somebody else the same way.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.