This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 2, "Punishing the Poor." Find more from that issue here.

Atlanta, Ga. — What a difference Oscar makes.

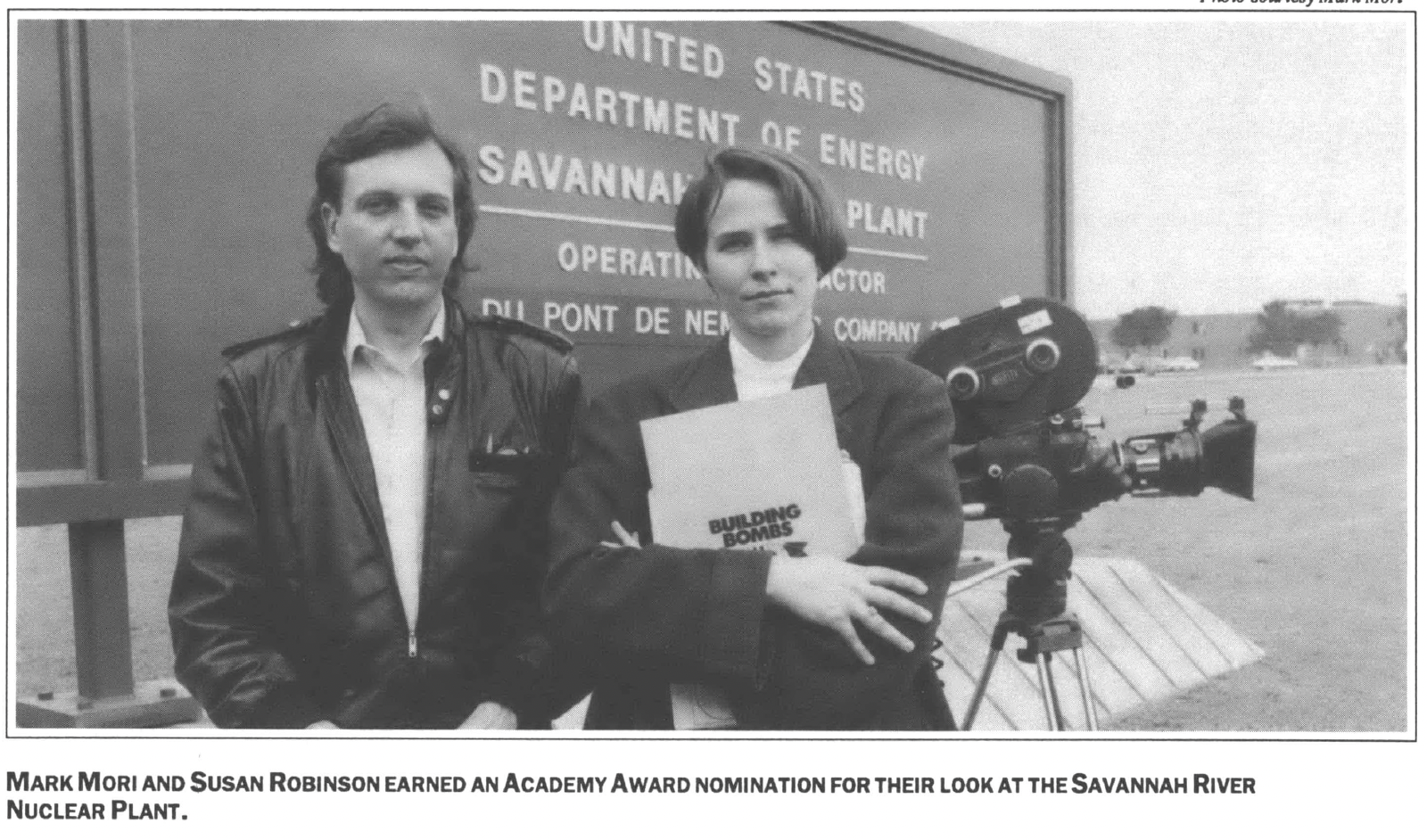

Atlanta filmmakers Mark Mori and Susan Robinson were already moving ahead on new projects when their 1989 documentary Building Bombs nabbed an Academy Award nomination last February.

The 55-minute film documents environmental hazards at the Savannah River Plant (SRP), the nuclear power and weapons factory in Aiken, South Carolina. Though it didn’t win the award, its presence in a strong, issues-oriented documentary field won a fresh burst of media attention for a modest, virtually hand-carved project that took its first-time directors a full five years to complete.

“It’s a major boost,” says Mori, who initiated production in 1984 as an extension of his lifelong political activism and his growing interest in filmmaking. “It meant we got blurbs in The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. People take my phone calls now. Libraries are buying it now. I mean, it’s the same movie. But some people who weren’t interested in it before — now, all of a sudden they want it.”

“It’s the Academy cachet,” Robinson agrees with a laugh.

The timing could not have been better. For local residents, Savannah River has been a source of both daily income and deadly contamination since it opened in 1950. Owned by the Department of Energy (DOE), the plant plays an essential role in the production of nuclear weapons, manufacturing tritium and plutonium-239 for hydrogen bombs.

Although safety violations have kept the plant closed since 1986, federal officials plan to restart one reactor this summer. The DOE also plans to open a new plutonium processing center at the site — the first entirely new plant to produce nuclear weapons since 1960.

Yet by all indications, troubles persist at the plant. In May, two top site officials were transferred amid charges of financial mismanagement involving millions of taxpayer dollars. The National Academy of Sciences has dubbed the plant “an American Chernobyl waiting to happen” — a conclusion that Building Bombs vigorously underlines.

Mori and Robinson, a freelance writer for corporate videos who joined the project in 1986, were granted a rare opportunity to shoot footage inside the plant, despite initial refusal of their request. As Mori recalls, a plant official asked camera operator Bruce Lane what sort of film he was making. Lane replied, “We’re not making a public relations film for you guys.”

That independent spirit is ringingly clear in the devastating arsenal of facts quoted with smooth authority by narrator Jane Alexander, star of the nuclear holocaust drama Testament. At one point, she tells viewers about 51 tanks at Savannah River that hold 35 million gallons of highly radioactive liquid waste — “the high-yield hangover from a 40-year binge of building bombs.”

The waste, she adds, is leaking into the soil — and the film brings home the danger by showing scenes of contaminated turtles wandering onto neighboring land.

Faustian Bargain

The film’s focus, however, is on the people who work at the plant. In scene after scene, Bombs introduces the men and women who profited from the economic boost the plant gave to an area where the primary industries had been farming and tourism — only to discover they were part of something they didn’t want to be a part of.

“We wanted to make a movie about the human side of this,” says Mori, who traveled to Aiken each weekend during the summer of 1984 to shoot footage of protest rallies. “We thought that people could get into this subject on the basis of people and their stories.”

Two former plant employees, physicist Arthur Dexter and engineer Bill Lawless, supply personal testimony of the almost Faustian bargain that the region struck with the Department of Energy and its original contractor, DuPont.

Dexter, now retired and active in antiplant protests, recalls how he embraced the chance to work at the site as a young man anxious to avoid the Korean War. Later, during the Vietnam era, he began to have profound doubts about his purpose, spurred by a visit to a vault stockpiled with 30,000 tritium containers — each one representing a bomb.

“I think that it’s ironic that in my zeal to avoid the Korean War, I wound up in a plant manufacturing the world’s most destructive weapons,” Dexter told the filmmakers.

Lawless became a thorn in the side of his employers. As environmental monitor at the plant, he quickly discovered that “only superficial reports could be sent to DuPont — and the more superficial, the better.”

Branded as an alarmist for blowing the whistle on health hazards at the factory, Lawless finally quit and went public with his findings about radioactive contamination, inadequate and outdated disposal, and threats to the Tuscaloosa Aquifer — a deep underground water source that runs from Alabama through north Georgia and into South Carolina.

Chillingly, the filmmakers intercut such nightmarish testimony with footage of children at play in pools of sparkling water. It’s a crude technique, but effective — as is the use of eerie, Twilight Zone-type music synched to aerial shots of the plant.

For the most part, though, Building Bombs is subtly constructed. Editor Philip Obrecht worked miracles stitching together a crazy-quilt assortment of archival footage, old DOE industrial films on the plant, and stunning scenes of workers tossing cardboard boxes of nuclear waste into trenches — the latter acquired from rolls of film shot during SRP’s early years.

No Chicken Little

Mori started the film after he bumped into Larry Robertson, an old acquaintance, at the Atlanta Film Festival. “I knew him from protesting the Vietnam War,” Mori recalls. “He wanted to get some experience as a cameraman, and said he would put together a crew if I would do a film on Savannah River.”

Mori got to work, raising the film’s initial $100,000 budget from such disparate sources as the Methodist Church, the Athens-based rock band R.E.M., and the Playboy Foundation. Robinson, who had protested at the nuclear plant as a teenager, signed on in 1986. “I could see she had a lot of talent,” Mori says. “It was wide open — anybody who wanted to come and help could join us.”

Mori knows the film breaks no news. But it illustrates public fears in vivid, personalized terms.

“When the whole Chernobyl thing was happening, we were actually on the plant site,” Mori says. “I remember saying to the cameraman, ‘Now tilt up to the reactor to show there’s no containment dome.’ Technically, the reactor is the same era as Chernobyl. I sort of got goose bumps when I heard the news on the radio.”

It’s that sort of feeling that the film conveys best. The Hollywood Reporter blurbed that it was a scarier viewing experience than Silence of the Lambs, and there’s a disquieting edge at work — more than enough to throw a few psychic speed bumps in the onrushing path of Reagan-era opportunists who’ve left their consciences on cruise control.

And yet, Building Bombs is a far cry from the despairing, Chicken Little school of documentary film, which identifies some harrowing transgression against humanity — atomic testing, political torture, poverty amid plenty — but never gets much past screaming about how awful it all is. Nor does the film terrorize its audiences with some perverse form of entertainment (instead of anonymous ski-masked serial killers, we’re stalked by lead poisoning!).

Instead, Bombs invites active participation in mobilizing against the danger at the Savannah River Plant.

“I wanted a film that would inspire activism — something that would encourage people to go out and do something,” Mori says. “In some of these films, you see some horrible nuclear explosion and then you go home depressed. I wanted the opposite kind of feeling — something hopeful, something uplifting, something inspiring.”

The key, Mori explains, was Dexter and Lawless. “We put these guys forward as role models. We designed it to say: ‘Here are people who are doing something. They are actually making a difference. Therefore, you can make a difference.’ And we showed that they changed. Here were guys who were pronuclear, who were in that plant, and who went through a process and confronted themselves. We emphasize that. Some people come out of it and think, ‘Well, what am I doing?’”

One of the people empowered by the film was Nancy Lewis, an environmental activist aligned with the grassroots organizations Campaign for a Prosperous Georgia and Georgians Against Nuclear Energy. “It was inspiring,” Lewis says. “Here were two people who were also in the neighborhood and busy with activist issues, who made a film. They showed me that a film was certainly something you could do, that you didn’t have to be a big Hollywood-backed production.”

Lewis got to work with a video camera to document community efforts to block a proposed hazardous waste incinerator in Taylor County, Georgia. The result was Burned, a half-hour video that features an opening comment from R.E.M. vocalist Michael Stipe. The tape, Lewis says, “has been seen by like a million community groups.”

Likewise, the groups Lewis works with have used Building Bombs in their organizing efforts, screening it for 40 or 50 people at a time as a touchstone for discussions. “It’s such a rallying point,” she says. “It tells a story in visual terms, rather than having somebody droll stand up there and speak.”

Drawls and Digressions

Although Bombs has been screened at 18 film festivals and won 14 awards, it has yet to receive a national broadcast in the United States. “It has been on TV more outside the U.S. than inside the U.S.,” says Mori.

The film has been shown several times on VH-1, the cable rock video network aimed at post-teen viewers, but Mori says the Public Broadcasting System rejected the work as too one-sided. “The issues raised in this film are important and it needs to be seen by the American people,” he says. “For PBS to say we don’t give enough say-so to the proponents of nuclear weapons is just ridiculous.”

To gain wider exposure for the film, Mori and Robinson are using grant money to supply a new, 30-minute version of Bombs to public schools, offer free satellite feeds to PBS stations nationwide, and give video cassettes to grassroots organizations.

Mori acknowledges that the conventional form of the film — it’s anti-slick, even down to the intentionally flat voiceovers of narrator Jane Alexander — met with some resistance.

“Some people didn’t understand,” he says. “When we went to New York and showed it to some anti-nuclear activists, they weren’t really that interested in the film. They wanted something that would be aimed at opinion leaders, but we wanted to influence Average Joe TV-watcher who’d be sitting there drinking a beer who’d maybe never heard of the Savannah River Plant.”

“We were urged to do just an expose,” he continues, “a very simple sort of thing. But we debated that and decided we didn’t want to do that. The film interweaves the environmental, the social, and the personal responsibility — rather than just telling a single point.”

The film was also shaped by its distinctively regional viewpoint, a sense of identity that goes well beyond the mere location of the camera’s subject.

“The fact that people talk with Southern drawls — we like that,” says Mori. “These are real people, and they say very intelligent things with a thick Southern drawl. For some people, that’s a contradiction.”

Robinson feels that the film’s Southern form separates it from standard docu-fare, establishing a laid-back tone that balances its urgent message.

“It’s been said of it that slowly it tells you there’s an emergency,” she says. “It makes digressions along the story line. It’s characteristic of a Southern storyteller that there are all sorts of little digressions that fold into one another.

“Some people would call this beating around the bush,” she notes. “Myself, I didn’t watch television between the ages of 7 and 16. I was used to hearing our neighbors in the country tell a ten-minute story about whatever the cow did that day. And every little point along the story had its own meaning and fun and eventually accumulated into this big laugh. A Northerner or someone from a more post-print culture would go crazy over this.

“The Californians who saw the film just went nuts because it took three minutes to get to the title,” Robinson adds with a laugh. “The Los Angeles people said, ‘Wow, you should start with this high-energy opening and grab them upfront.’ But to me, that sensibility didn’t really fit the story we were telling. It’s about this ambling area that’s suddenly taken over by a force much greater than its own.”

Deploying some of the clever collage techniques that served the ironic, 1982 documentary The Atomic Cafe so well, the filmmakers include a bluegrass number called “The Death of Ellenton” over footage of one of the old South Carolina cotton towns paved over to make way for the Savannah River Plant. “

The song was originally written by a man in the town,” says Robinson. The film’s synthesizer score, she adds, “tries to mimic the way the guitar would be played. And we tried to use a little bit of electronic fiddle instrumentation.”

No Comment

The Department of Energy has steadfastly refused any public comment on the film. But in the end, Bombs has won some grudging respect from officials at the Savannah River Plant.

Shortly before the Academy Award nominations were announced, Mori and Robinson returned to the plant to tape a segment for WTBS-TV in Atlanta. At first, DOE officials refused to let them in. “They told us we weren’t allowed on the property,” says Mori, “but then they realized that looked kind of bad.”

Greeted at last by a DOE spokesman, Mori recalls receiving the mildest sort of praise, carefully couched in hospitable words: “He told us, ‘I understand congratulations are in order.’”

But as Building Bombs sees it, the real congratulations belong to those who have struggled to confront the danger at Savannah River — and to accept their own responsibility in standing up to the nuclear threat.

“I slowly began to confront myself,” engineer Bill Lawless told the filmmakers. “It’s a very slow process, a very difficult process for most people — at least it was for me — to confront yourself and to come to terms with it and then to finally start doing what you think is right. The more you do it, the easier it becomes.”

“I Watched My Hometown Die”

The following excerpt from the script of Building Bombs tells the story of the early days of the Savannah River Plant, when thousands of families were uprooted to make way for the world ’s first hydrogen bomb factory:

EVELYN COUCH WALKING THROUGH WOODS

NARRATOR: The Ellenton, South Carolina birthplace of Evelyn Couch was condemned by the government to build the Savannah River Plant. That was just the beginning of a startling change in her life.

COUCH AT KITCHEN TABLE: From the way I would describe it, it was almost like the Gold Rush days — everybody coming in from everywhere all over the United States to work. We had 35,000 people to move in here, you know, where we had a 13,000 population, so you can know what that can do.

EXTERIOR OF B&W TRAILER

COUCH VOICE OVER: We even turned horse stables into apartments. We had a lot of trailer courts set up, a lot of new towns and communities set up.

JAMES GAVER, DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY: I think the relationship between the communities surrounding the Savannah River Plant and the operation itself and the people who work here is very, very good, it’s very strong. It has taken some time for it to get to that point.

AERIAL VIEW OF PLANT

NARRATOR: To make way for the world’s first hydrogen bomb manufacturing complex, the Atomic Energy Commission swallowed up 300 square miles in three counties. . .

CLOSE UP OF HOUSE WITH BARBED WIRE

. . . an area four times the size of Washington, DC. Whole towns were wiped off the map forever.

TRUCKS MOVING HOUSES

6,000 people in 1,500 families had to move.

BULLDOZER UNEARTHING GRAVES

Even the dead left their final resting place. Evelyn’s homeplace became a temporary office for Dupont.

GAVER: The construction of SRP is listed in the Guinness Book of World Records and it certainly is one of the largest construction projects that has been undertaken in modern times.

COUCH: They had to move the people out and bought their land. Some got a fair price for it . . . not many got the fair price that they could set up another place to live in at all.

FARMER ON TRACTOR WATCHES MOVING HOUSES

BLACKS EMERGE FROM RAMSHACKLE HOUSE

GAVER: Uh, those relocations were done without a great deal of turmoil or upset. Of course, there were deep family ties to some of the areas, to some of the small towns, and naturally those people hated to leave.

COUCH: They had one couple in the area that refused to sell. They had lived in this old home place, a brother and a sister, and they got their shotguns out, but then they put them in a mental institution and took the land anyway.

CLOSE UP OF ELLENTON PROTEST SIGN

SONG: Where the broad Savannah flows along

to meet the mighty sea,

there stood a peaceful village that

meant all the world to me.

‘Twas a home of happy people,

I knew each and every one,

All my kin and all the friends I loved,

the town was Ellenton.

ZOOM IN ENERGY COMMISSION STREET SIGNS

But the military came one day

and filled our hearts with woe,

We’ll study war right here, they said,

the little town must go.

Then they came with trucks and dynamite,

the din and dust rose high,

STILL OF CONSTRUCTION WORKERS EATING LUNCH

And I stood encased in silence there

and watched my hometown die.

Tags

Steve Dollar

Steve Dollar is a writer for The Atlanta Constitution. (1991)