This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 1, "The Golden Child." Find more from that issue here.

We keep digging. It’s hot. Goddamn it’s hot and the sweat keeps getting in my eyes. But we keep digging. Me and Halsey, mindless with these shovels. I already broke one shovel. Broke it off at the handle. Johnson, he went and got it fixed though before I had the chance to take a smoke. I wonder about Johnson. I mean he’s my boss and been my boss for the past seven years, but I still wonder.

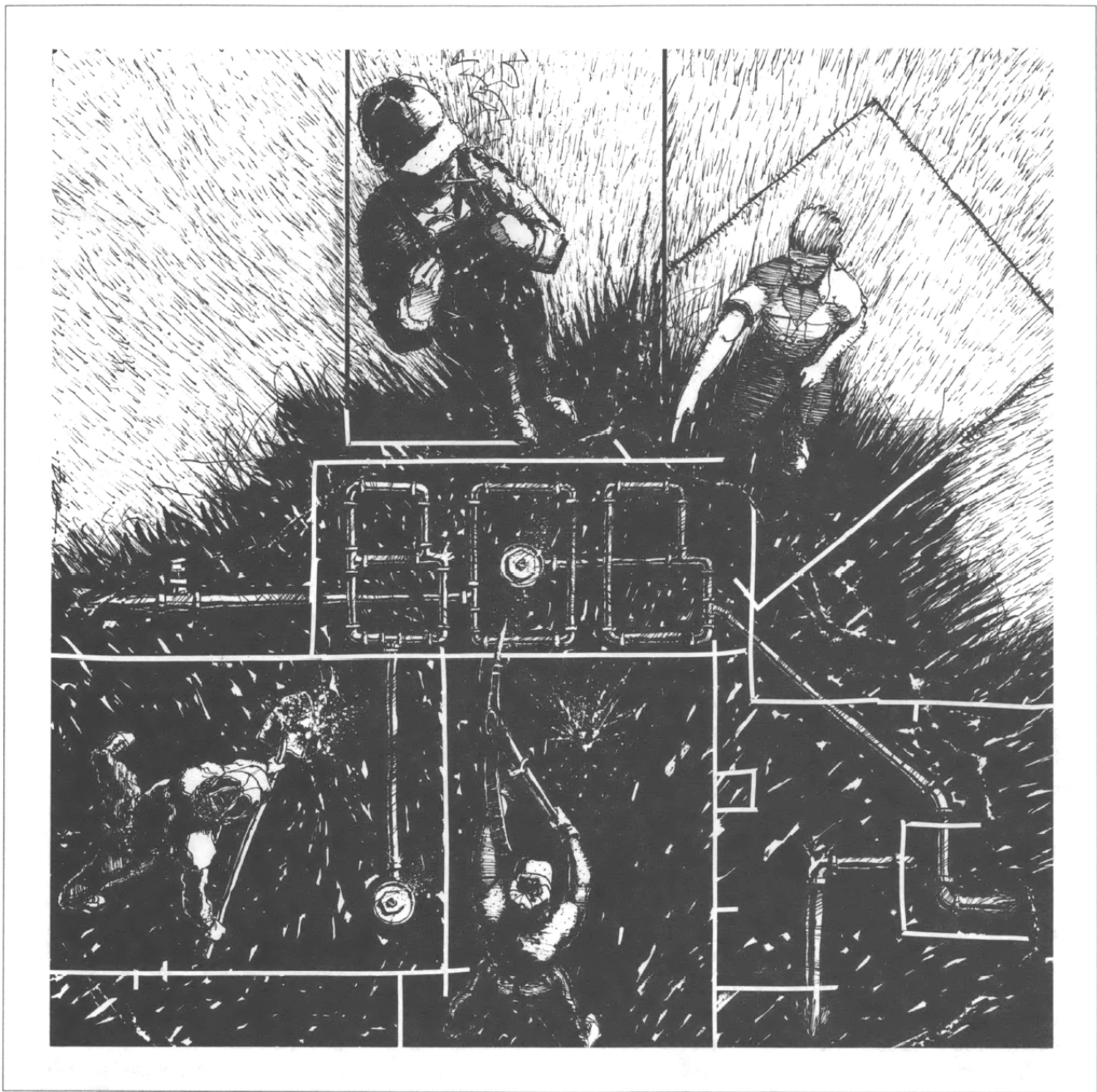

The well we’re searching for, digging up half the damn delta for, is an artesian well. That’s pure drinking water that flows up of its own pressure. They say it’s seventeen hundred and forty-two feet deep. Mr. Nick says that. He’s retired now, but he used to work for City Water and even though this ain’t City Water Mr. Nick knows what he’s talking about. He says the well was first drilled back in 1904 and it’s been going ever since. Now Miss Mary is getting gaps of air in the water up to the house and so we got to find the well before we call the plumbing men in to drill it back out. The well’s down next to the bayou. It’s on the bank of the bayou and the mosquitoes are awful. And we’re working so hard and wiping sweat we don’t have time or energy to be slapping every one of the little sonsofbitches that decides to suck out our blood. I’ll tell you they’re hell. God fucked up when he made mosquitoes. But the well, it’s covered by a plywood kind of roof. In fact, it looks like the doors to one of them storm cellars you see out in Kansas. But this ain’t Kansas and that ain’t really the well. It’s just the works that go to the well. Mr. Nick says the well has to be close though. And we’re digging. The mosquitoes are biting like hell. Mr. Nick is standing above us on the bank with a smoke and Johnson is squatting down looking hard at every shovelful of dirt we bring up. He’s eyeing an old Coke bottle and rusted broken pipe and cinderblocks that were dumped in as filler. Saying, “Come on, boys, let’s find that bitching well.” And Halsey is sweating bad. I look over and the sweat is just pouring out on his black ass. He looks up and shakes his head and drips of sweat shake off his kinky hair out from under his green cap.

“When Mr. Bob put this plumbing in,” Mr. Nick says, is saying, “it was just before he died, just before the cancer took him.” Mr. Nick scratches his morning beard. I see Johnson glance up at Mr. Nick. He don’t like nobody talking about how Mr. Bob done things when he was alive. When Mr. Bob died Miss Mary had hired Johnson on temporarily to oversee the farm until she could find herself a permanent manager, but then Johnson had made good crop and she’d hired him on again. Then they’d married that second winter right after the harvest. After they’d married we’d had to change everything so it wouldn’t be like Mr. Bob had done it. He changed the time we came to work from seven o’clock to six o’clock. He changed the poison we sprayed with to Poast. He even went so far as to change the color of the shop from a rust red to an off-yellow. Johnson fired the rest of the labor that Mr. Bob had had working for him, but I was a third cousin to Miss Mary and so my job had been pretty safe. That was seven years ago. He changed everything. It wasn’t that the changes were bad, just that they were changes.

“Yes, sir, some of the damndest plumbing I ever seen,” Mr. Nick says and flips away his smoke. “Don’t get me wrong, Bobby knew what the hell he was doing, he just had his own way of doing it.” I hear Mr. Nick chuckle and then cough and spit. “That Bob was a hell of a man, a hell of a farmer.” Mr. Nick goes to laughing then hacking again. “I don’t guess there wasn’t nothing that old boy couldn’t do.”

And Johnson says, “Find that bitching well, boys, come on now.”

My shovel clangs metal and Halsey stops digging. I slap at the damn mosquitoes. Every time we hit metal I pray it will be the well so we can stop digging. I bend down and brush the dirt away. It’s another pipe. All around us is this tangled mess of pipe, the hum of the big bullet-shaped pump set right smack in the center of them. We’ve already found the rust-colored overflow tank. We’ve already dug out from that and followed these pipes that shoot out or lead back into it. And every time we start a new direction the first thing we’ve got to do is dig straight down over four feet and then widen the hole and search out from it. We’ve already done that, plenty.

Johnson’s rooting around in the dirt at my feet. He’d hopped right down into the hole as soon as I struck metal. He isn’t big. He’s skinny and grub-white looking with thin blonde hair. He has on khakis and a short-sleeve button-down and he never wears a cap. Mr. Bob had always worn a cap, but he was going bald from those treatments. But even before those treatments he always wore a cap. He had been a big man, heavy, and he’d get right down in a hole with you and grab up a shovel or if we were irrigating the cotton he’d be in the mud and the water lifting pipe and splashing right alongside us.

“It’s just another goddamned pipe,” Johnson says.

Mr. Nick laughs. “Yes, siree. Damndest plumbing I ever seen.” He slaps his arm.

Johnson stands up and puts his hands on his hips and kind of glares at Mr. Nick. But Mr. Nick is lighting up another smoke and he don’t see him. Johnson scrambles up out of the hole to squat on the edge again. He looks like a toad squatting there. “Follow that pipe,” he says.

“Yes, sir,” I say. I look at Halsey and Halsey looks up at me and then he shakes that sweat free again and I wipe my face with the back of my glove and we start digging again. My shoulders are starting to ache with the steady thunk thunk thunk of the shovel and then having to lift that dirt up high to dump it out on the bank. Mr. Nick comes over and looks closer into the hole. He pulls the smoke from his mouth and stares at it while he thinks. The thumb of his other hand’s hooked under the strap of his overalls, his hair oiled back and these thick-rimmed black glasses with a wide strap around his head to hold them on for him.

“Boys,” he says. “I do believe that’s the wrong direction.”

We stop digging and lean on our shovels. Halsey lights up a smoke quick and passes me one. God it’s good. I blow a cloud of smoke at the black dots hovering around me.

“I remember the day Bobby sunk the bulk of this in. I remember that like it was yesterday, but I sure as hell can’t remember exactly where that well is.” He slides a hand through the slick of his hair and rests his palm against the back of his neck. “But it seems to me, the well ought to follow that pipe,” he says and points to one of the pipes that comes out of the overflow tank, “and go to right there.” He picks up a pebble and tosses it into the hole right near the pump itself. It follows one of the pipes from the overflow tank and disappears into the dirt and part of the old cinderblock wall which is left surrounding the pump.

Johnson stands and stares at the place almost under the pump where the pebble has landed. It made good sense to me. I look at Halsey and he shrugs. Johnson says, “I don’t believe that’s it, Mr. Nick.” Halsey looks at me and I shrug.

“Well,” Mr. Nick says and drops the cigarette butt into the hole, “you can dig all day if you like, but I believe the well is there.”

Johnson kind of nods. “It may be, but I got this feeling ” He don’t finish it.

Mr. Nick looks at his watch. “I’m going to go get myself some lunch over to Nadine’s. These mosquitoes are like to drive me crazy. I’ll stop by this afternoon sometime if I get a chance.” He looks at us. “See you boys later.”

“I appreciate your help, Mr. Nick,” Johnson says.

“Okay.” Mr. Nick shakes his head as he walks over and gets in his truck. He beeps his horn and then he roars off not even glancing sideways at us.

Johnson stares down into the hole for a long time after that, rubbing his chin. He cuts his eyes at the sun, checks it against his watch. “Let’s break for lunch. Be back here at one o’clock and we’ll find the bastard.”

We lean our shovels against the walls of the hole and climb out. I’m covered with dirt where the sweat has made it stick.

“Mason,” Johnson says to me, “take the red truck and pick up the rest of the men. Remember to be back here at one o’clock.” I nod and me and Halsey get our coolers and carry them to the truck. Johnson still stands over the hole. It reminds me of a man looking down into an opened grave.

I start the truck and back it onto the road. I look beside me at Halsey. He’s lighting a cigarette.

“Damn!” he says.

“I’m telling you what.” I turn on the radio and we don’t say much else as we drive through the green rowed cotton fields and pick up the rest of the labor.

Johnson’s already at the well when we get back there at one. Maybe he didn’t even go to lunch. He looks down at his watch but doesn’t say anything. We climb back down into the hole. I pull on my gloves and get my shovel.

“There,” Johnson says, “dig there.” He points back toward the overflow tank to the other pipe that pokes out of it. I look at Halsey but Halsey is looking up at Johnson. I sigh and step over the tangle of pipe and red and blue valves and stomp my shovel into the dirt. It’s clay. I stomp again and pull it up. It’s heavy. Halsey is working beside me as best he can. We have to start by widening the hole again. I get the pick and that works a little better in the clay. Johnson stands on the bank and watches. I start to sweat again. We hit more broken-up cinderblock. I think how it might not have been so bad to have been fired. “Come on, Mason, dig.” I look up at Johnson who’s now squatting on the edge and is leaning out over it to see even deeper into the hole. A cloud of mosquitoes hovers around his head, swarming him. To me, this sure as hell don’t look like the pipe to the well. But I don’t say word one to him.

Raking the sides with the pick, I let the dirt slide down into the hole around the pipe and Halsey shovels it out. I bite the pick in to pry off a wall and a thick gel like snot shoots up into the air. I hear Johnson give a loud, “What the!” and see him stagger back from the hole. He trips on the rough clods and tumbles over backwards down the slope. The dirt he’s kicked up slides down the face, leaving thirteen white snake eggs in a little hollow place tucked away in the earth. They were hiding there.

I poke one with the sharp end of the pick. It’s soft and white and they’re all stuck together like marshmallows in the heat. The one I’m poking at spurts out a greenish gob.

“What in the hell was that?” Johnson yells, stumbling back over the pile to the hole, dusting off his palms and elbows. He frowns down at his front shirt pocket which is shiny-slick where the green goop got him and pulls a handkerchief out of his back pocket to wipe at it.

“Snake eggs,” I tell him.

He stops and looks down at his handkerchief. “Are they poisonous?” He looks right at me, but I just shrug. Halsey’s touching them with his shovel. He scoops them out and flips them up on the bank near Johnson’s feet. Johnson leaps away.

“Watch it! You goddamn idiot!”

You can’t tell it by just looking, but I know Halsey got a kick out of that. Johnson peers close at the eggs still glued together and nasty-looking. “Give me your shovel, Halsey.”

Halsey hands the shovel up to him and Johnson takes it. Halsey looks at me. We both watch as Johnson presses on the eggs and rolls them about. Pokes them. He pries a couple of them apart. Bending down, he touches one with his finger. It presses in with that pressure. Soft as anything. Johnson takes a giant-step back and we watch him as he swings the shovel up high over his head. “Watch it!” I yell as he flails it down with a hard flat slap against the eggs. Shit spits out everywhere from under the shovel. As I turn away I feel some of it spurt hot and wet on the back of my neck. I hear Halsey yell, “Goddamn!” Johnson stands up over us, above us, breathing hard, the shovel all smeared with that green stuff. He peeks under it. All of the eggs are squished out. Just the skins, wrinkled flat, remain.

Johnson scrapes the shovel against the dirt, wipes it as clean as he can and hands it back to Halsey who takes it back at arms-length. He don’t say nothing. We don’t say nothing neither. Halsey turns toward me, arching an eyebrow up, and then we start our digging again. We dig on that one pipe for a long time. Finally, Johnson tells us to start digging where Mr. Nick showed us.

By now it is late afternoon. The sun’s long-angled through the cypress in the bayou and the crickets are going strong, the cicadas too. We don’t talk much. I’m too damn tired to talk at all. My shirt’s soaked through with old sweat and new sweat. It chills me. My whole body feels like one big itch.

Johnson stays squatted over the edge and watches. I don’t believe he blinks or ever looks away. The hole is now over twice the size it was when we started that morning. The dirt is piled high all around us, making the hole even deeper. Pipes lay exposed that haven’t seen air for maybe eighty years or at least since Mr. Bob fooled with them. They crisscross each other and strike out into the ground in every direction, carrying water up to Miss Mary’s house and God only knows where else. The pump goes on with its even hum. Valves with blue and red and black handles poke up over the pipes they control. We keep digging.

Halsey strikes metal again. He looks at me, leaning his elbows on his knees, then up at Johnson.

“Dig it up,” Johnson says.

Me and Halsey take turns at it. Both of us can’t work directly on it because of the pipes that run over it and the closeness of the pump. It’s a big pipe, thick. We shovel out the dirt and then I get down on my hands and knees so I can brush and scoop out the dirt around the turn in the neck of the pipe with my hands. I see the “W” on the big bolt in the valve where it turns straight down.

I look back at Johnson. He’s squatted there. It seems he’s hovering over the hole. His eyes stare at my hands on the well. They’re wide-open and unblinking. He sways with his intensity. I nod, “It’s the well, Mr. Johnson.” He still stares, staring, and then he lets out this big breath. He breaks his eyes from the well and blinks out over our heads. Then he looks off toward the house.

“Right,” he says. “All right. That’s a day. Go on and pick up the rest of the men. I’ll call the plumbers tonight and tomorrow, first thing, we’ll rip this entire mess out and do it right.”

Me and Halsey collect the shovels and the pick and climb up out of the hole. We lug all of the tools to the truck and throw them in the back. I watch Johnson still squatting over the hole. I start the truck and back out onto the road. I turn back in time to see Johnson jump down into the hole and disappear. I look over at Halsey and he’s sucking on a smoke, watching too. He leans back and blows smoke. “Urn,” he says and flicks his ash out the window. “It’s Miller time,” I say to him and he nods. I’m betting Mr. Nick will be waiting for us at Nadine’s to hear. Sure, we found it, I hear myself say — and worn out as I am from it now I can feel myself shaking my head for him then — telling Mr. Nick, The poor sonofabitch. I put the truck in gear and drive out slow till I hit the corner, then I stomp the pedal to the floor.

Tags

Tom Bailey

Tom Bailey was born in Indianola, Mississippi and grew up trailing his father, a Marine Corps aviator, around the South. His work has been selected for Streetsongs: New Voices in Fiction and New Stories from the South. He is currently completing a novel at The State University of New York at Binghamton. (1991)