The Way Things Are

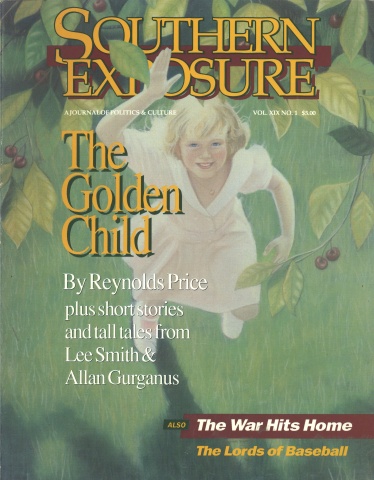

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 1, "The Golden Child." Find more from that issue here.

The second we walk in I know it’s all wrong. The two girls riding the bikes, the others trapped in the machines, they’re trying too hard not to look at us.

“Shit,” Johnny says out the comer of his mouth. “I didn’t know we was suppose to wear a costume.”

Johnny’s trying to make a joke, but like me he’s looking in the mirror that covers the back wall. He sees what I see — two guys getting a little too big in the belly wearing t-shirts and cut-off jeans, with mortar on our arms, some in our beards. They don’t put mirrors in port-a-johns.

“Damn if I don’t believe these people shower before they work out,” Johnny says.

Two guys wearing tight shirts with Nautilus written on the front are within spitting distance. The older looking one, about our age, helps a woman do some negatives. The younger guy sits on the free-weight bench, doing nothing. We wait.

“Let’s get out of here,” I say finally. Johnny shakes his head, like a bull starting to madden up.

“I paid five dollars for that coupon book,” he says. “All I got so far is a half-price hamburger at Hardee’s and a free salad at Quincy’s.”

I know Johnny. We played six years of junior high and high school football together, most of the time side-by-side on the offensive line. I know there’s no use in saying anything else. He ain’t leaving.

And they realize it too, the coaches, the trainers, whatever you call them. The younger one gets off his ass, comes over and asks can he help us, like maybe we’re just lost and come in to get directions.

Johnny takes out the book and tears out the coupon. He’s got muscles, this guy, the kind that you can see right through his clothes, but when he opens his hand to take Johnny’s coupon you can tell the hardest work he’s ever done with his hands is jack off. He reads the coupon.

“OK,” he says, “but you understand this coupon is good for only one workout. A year’s membership is three hundred dollars.”

I almost say that we’re not stupid. And then I almost say we can read, too. But I end up not saying a damn thing. He starts Johnny on the first machine, but not before he goes and gets a towel so he can wipe each machine when Johnny finishes. They start down the line, him talking to Johnny, explaining the machines, but he ain’t looking at Johnny, like if he keeps looking away maybe Johnny will disappear.

I walk over to where Johnny’s pushing about a ton on the leg machine, sweating and stinking and grunting till he finally can lock his legs.

I tell him I’m going out to the car. Johnny lets the weights clang back down, rubs his knee.

“But the coupon’s for two people,” he says, trying to catch his breath.

“I done sweated enough today just making a living,” I say, then walk out into the heat.

The air conditioner’s been broke for a year, so I roll down the window. Johnny comes hobbling out thirty minutes later.

“Sorry you had to wait,” he says. He’s gritting his teeth when he says it, flexing his leg. He don’t have to tell me he’s rehurt the knee the doctors cut on after our senior year.

“No problem,” I say. “I ain’t got nothing better to do.”

“I showed that candy-ass a thing or two,” he says. “Asked him what he did on that leg machine, then did ten more pounds.”

Johnny reaches into a paper bag he’s got his work clothes in, pulls out two cans of Gatorade.

“Little treat,” he says. “Got ’em out of the machine right before we punched out.”

Even warm Gatorade tastes good when you been working out in the sun all day. It takes about two swallows to empty the can, and I’m wishing I had another.

“Don’t think I’m going to join,” Johnny says, crushing his can and putting it in the bag. “It ain’t like when we lifted for football. Hell, it don’t even smell right in there — no Atomic Balm, no Ben-Gay. Nobody yelling. Nobody sweating. It just ain’t for me.”

“Me either,” I say, getting my keys out.

“Those girls on the bikes were good looking, though,” Johnny says. “College girls, I reckon.”

“I reckon,” I say, cranking up the car, not wanting to talk about it no more. “Where we going?”

“You got something else to wear in the trunk?” Johnny asks.

I nod.

“Let’s go over to my apartment then,” Johnny says. “Get something to eat, then go to the Firefly. Hell, I’ll even let you take a shower provided you ain’t got any cooties.”

Bocephus is singing “The Pressure is On,” so I turn it up and burn some rubber leaving the parking lot.

I almost feel decent by the time we turn into Johnny’s apartment. A couple of black guys are out front drinking Schlitz Malt Liquors. They got their backs to us but they can see me and Johnny because one of those mirrors that lets you see around comers is right above them. They’re in Johnny’s yard, if you can call dirt and weeds a yard, but they move on out into the parking lot, their backs still to us, keeping their distance. L.J., the black guy who works with me and Johnny, he swears the only white guys black people are scared of is guys like us with long hair and beards. Too many motherfuckers that look like that is dangerous crazy, L.J. says, like Charlie Manson and the one in Philadelphia that cut women up in little pieces then ate them. I don’t know if that has anything to do with it or not, but the black guys keep their distance, don’t even look our way.

We get a shower, eat a couple of TV dinners apiece, then head over to the Firefly.

It’s Tuesday so Freeda’s working the bar by herself. We come in and it takes her a little too long to get up from her stool. You can tell she’s bone-tired, but ain’t we all. She knows what we drink so she opens two long-neck Buds, puts them on the counter. Johnny gets his and limps over to the poker machine. His leg’s starting to stiffen up, and I hope like hell he hasn’t messed it up bad, because he don’t have a dime’s worth of insurance.

Freeda sits back down on the stool. She’s filling out some kind of government form, like what they give you for taxes, but it’s probably something to do with her kids. She’s got three of them, and no husband, at least not any more, so she lives with her mother and works here two-to-two, six days a week.

I used to think Freeda was a lot older than me and Johnny, but she says she saw us play ball in high school, screaming for her school, Burns, to kick our asses. Johnny likes to remind her they never did.

I’m thinking about all this when two necktie types come in, sit in one of the booths in the far comer. Instead of going up to the bar, they make Freeda come to them, then start giving her shit for not having any imported beers, like she owns the place and decides what beers to carry. But that’s the way things are. If you work there’s always somebody giving you shit about something. And if you ’re like Freeda and you got three kids and an ex-husband who won’t pay his alimony, you smile while they rub your face in it. And that’s what Freeda is doing, smiling, hoping for a good tip.

They finally order and Freeda brings their beers. The one closest to the door says something to Freeda but I can’t hear what it is since Johnny’s cussing the poker machine. Then he grabs one of her breasts. I can’t believe it. It’s dark so maybe I’m just thinking I saw him do it. But Freeda’s coming back toward me and her head is down. She’s trying not to let them see she’s crying.

I’m off the stool and in his face. “What can I do for you?” the necktie closest to the door says. He talks smooth, like a lawyer.

“Give me a chance to kick your ass,” I say, loud, right in his face. He’s as big as me but soft, and not just in the belly. I can take him. Johnny’s coming up behind me. Even with a bum knee he can take care of the other one.

“I don’t want any trouble,” the necktie says.

No, I’m thinking. You just want to give it. Freeda’s beside me now, with their drinks. She heard enough to know what’s going on.

“It’s OK,” she says. “He didn’t mean nothing by it.”

The necktie finally catches on, understands why I’m pissed off.

“The lady’s right,” he says. “I didn’t mean anything.”

Freeda wedges between me and him, puts the drinks on the table.

“Please,” she says to me. “You’re making trouble for me.”

She turns to Johnny.

“Help me, Johnny,” she says.

Johnny don’t know half of what’s going on, but he’s ready to fight, at least until Freeda says that. He untightens his fist, backs off a little.

“Come on back to the bar,” she tells me and Johnny. “I’ll get you boys a beer, on the house.”

Freeda takes my hand like I’m a little kid, leads me back over to the bar. She gets our beers then goes back to the booth. She’s talking soft but I hear enough to know she’s apologizing. Johnny loses some more money playing the poker machine while I sip my beer and try not to look in the mirror behind the bar.

Tags

Ron Rash

Ron Rash was born in Chester, South Carolina and raised in Boiling Springs, North Carolina. A recipient of the 1987 General Electric Younger Writer’s Award, he has published in Special Report, Southern Review, and Texas Review. He teaches at Tri-County Technical College in Pendleton, South Carolina. (1991)