This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 1, "The Golden Child." Find more from that issue here.

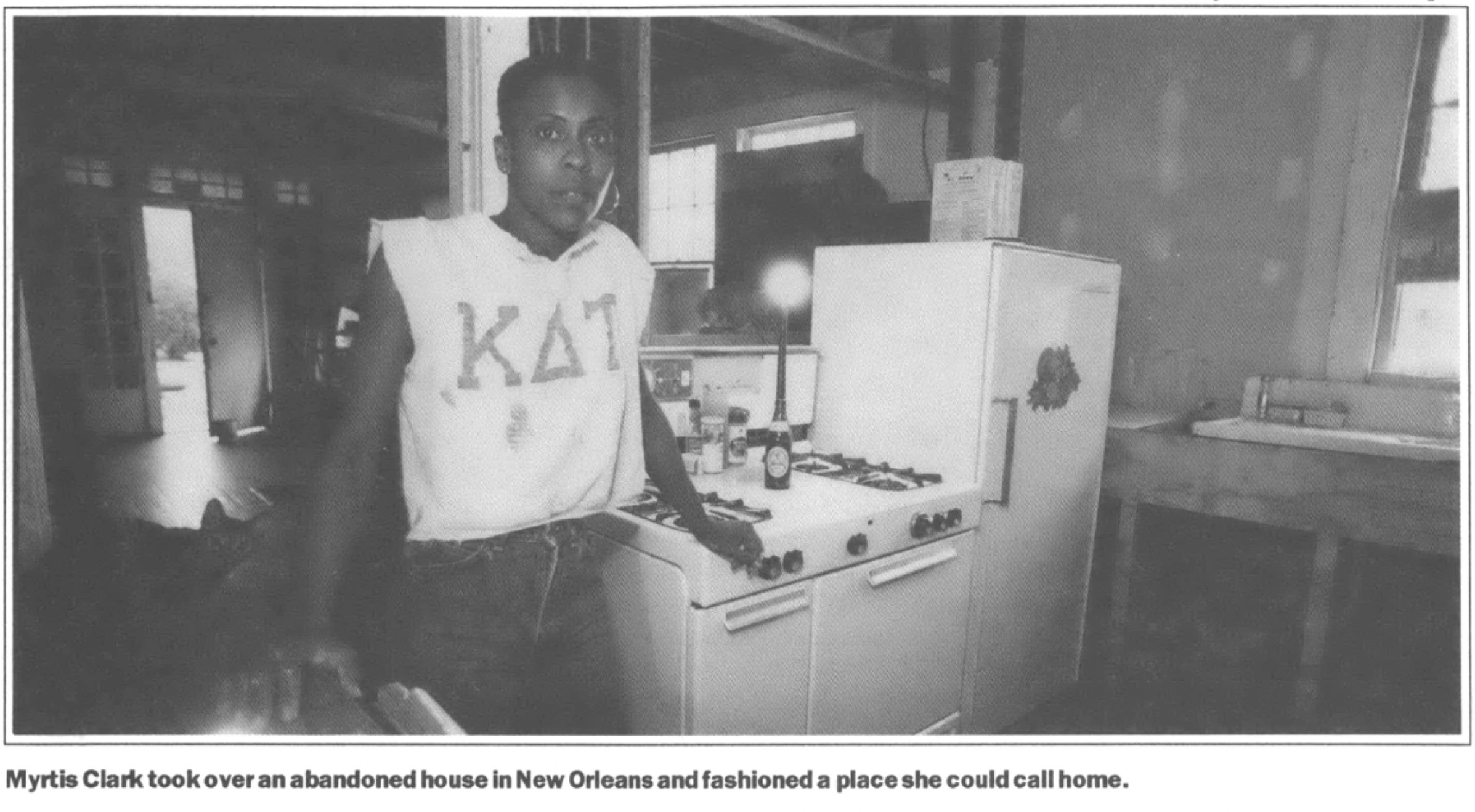

New Orleans, La. — Eighteen years of moving from apartment to apartment, at the mercy of capricious landlords and real estate agents, had taken its toll on 37-year-old Myrtis Clark. When her last landlord evicted her for complaining about an abusive neighbor, she decided she’d had enough. As a member of ACORN, a grassroots organizing group, she obtained a list of vacant government-owned houses that she was eligible to bid on. Her next move was calculated — and illegal. On October 13, 1990, with the backing of ACORN, Clark tore the planks off a house that had been boarded up for two years and staked her claim. Clark had become a squatter.

With the help of friends and neighbors, Clark got down to work on the house, long ravaged by time and vandals. A dry-wall finisher by trade, she spent months hammering up holes, gutting internal walls, replacing gyprock and broken windows, and ripping out ceilings to expose the rafters for a light, airy look. The interior of the small woodframe house was a riot of planks, nails and cartons, out of which Clark fashioned a place she could call home.

Tall and slim, Clark stretched out her long legs as she sat at her kitchen table on a warm fall day last November. The drone of lawnmowers drifted through the open window. Clark had already been accepted by her neighbors on Pauline Street, located in a modest, quiet, predominantly black part of New Orleans. They were pleased to see the place occupied after standing vacant for two years. Ugly boards no longer covered the doors and windows, and the small lawn was neat and tidy. More important, the house no longer stood open to drug dealers, as did other abandoned houses in the neighborhood.

Clark felt lucky. ‘There are so many people who would love to move in and have a roof over their heads,” she said. “I need this place. If I didn’t have it, I’d be out in the street.”

Uncle Sam, Realtor

The house Clark occupied is owned by the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC), the massive federal agency created by Congress in August 1989 to sell off assets from hundreds of failed savings and loans. Now the largest real estate dealer in the world, the RTC says it has tried to sell properties as quickly as possible without disrupting the real estate market. It has been roundly criticized, however, for handing over many valuable assets to large financial institutions at bargain-basement prices, even paying some banks to take deposits worth millions.

By the time it’s over, the bailout of the S&L industry is expected to cost every taxpayer at least $14,000. Even worse, the bailout is doing little to hold the industry accountable to its original purpose: helping ordinary Americans buy their own homes. As unemployment and real estate costs soared during the past decade, home ownership plummeted and homelessness reached crisis proportions. Many S&Ls, meanwhile, gambled deposits on junk bonds and other risky investments.

Pressured by the Financial Democracy Campaign, a national coalition of church, labor, and citizen groups like ACORN, Congress ordered the RTC to help ease the shortage of affordable housing by marketing its 37,000 residential properties to those who need them most. The agency has a clear mandate to offer discount prices and special financing to low-and moderate-income homebuyers like Myrtis Clark, and to non-profit groups like ACORN.

But in its first year and a half in the real estate business, the RTC has dragged its feet on affordable housing. Although the agency has given big investors cut-rate deals on real estate, it has shown little interest in providing discounts and seller financing for low-cost homes. (See sidebar.)

The result? “Untold thousands of eligible properties have been sold to speculators,” says Tom Schlesinger, director of the non-profit Southern Finance Project based in Charlotte, North Carolina. “Poor and middle-income homebuyers, housing nonprofits and public authorities have been locked out of the market.”

U.S. Representative Barney Frank of Massachusetts is even more emphatic: “I’ve never seen a program administered less sympathetically.”

The human cost of RTC stonewalling is apparent in New Orleans, where an estimated 8,000 people are homeless in a city full of vacant homes. Sixty-one percent of the city is black, and the neighborhood in which Clark staked her claim — like most black working-class areas of the city — is dotted with abandoned houses owned by the government. Among them are comfortable homes, architectural jewels built a century ago by German immigrants and sheltered by hundred-year-old oak trees lining the streets.

The housing trouble began when the domestic oil crisis struck New Orleans in 1984 and forced many renting families to move in with friends and relatives to save money. Absentee landlords who had borrowed heavily from savings and loans to get cash for their investments suddenly found themselves without tenants, and with no means to repay their debts. By the end of the 1980s, banks and S&Ls had foreclosed on many homes. Street after street was blighted by boarded-up homes falling into disrepair. New Orleans, the city never too poor to party, was looking mighty ragged.

Then the savings and loan crisis hit. Dozens of S&Ls failed, throwing hundreds of homes into the hands of the RTC. Only Texas suffered more than Louisiana, where, as of last September, the RTC controlled 19 failed S&Ls with $2.4 billion in assets. The agency lists 727 residential properties in New Orleans, all but 83 of which qualify for the affordable housing program. To date, only 10 properties in the city have been sold under the program.

Today almost every block of working-class neighborhoods in New Orleans is home to at least one vacant and vandalized property, ultimately owned by Uncle Sam. Sighs city housing official Sheila Danzey: “Everything in New Orleans is ‘for sale’ or ‘foreclosed.’”

Home Sweet Squat

Despite the large number of vacant homes and the far larger number of homeless residents in New Orleans, few people have had the courage to simply take over abandoned houses. The day Clark began her squat, she recalls, the front door yielded immediately to reveal a dirty interior with broken windows and cracked walls. She placed a bid on the house with the RTC, hoping to have the $13,000 price tag reduced to account for the labor and materials she supplied.

Before long, an agent from the RTC’s management company dropped by and asked Clark if she realized she was trespassing. The house was under contract from a buyer, he told her. She knew, she said. She was the buyer.

The agent told Clark that the police were on their way to throw her out, but a flurry of calls averted the move. Clark was permitted to stay, provided she take out insurance.

For Clark, squatting in the house meant more than asserting her right to a secure shelter. It was also an opportunity to help fix the damage done by wealthy investors who snapped up houses during the oil boom and walked away when times grew tough.

Indeed, the vacant houses left behind are drawing crime to neighborhoods where few people lock their doors. “Not too long ago one of the RTC houses on the comer was being used as a crack house, and a neighbor’s little brother was robbed,” says Sarah Dave, who has lived on the same street for 14 years. “Some city officials want to tear down the crack houses, but there are a lot of people here who would like to buy those homes. I really get upset, because the city wouldn’t allow vacant houses like these to just sit in an elite neighborhood like the Garden District.”

But those who need the houses the most may have the hardest time buying them. Seventy percent of New Orleans residents are renters, and 30 percent live below the poverty line. “We have a tremendous hidden homeless population — whole families of renters who have lost their homes and have moved in with friends or relatives,” says Beth Butler of ACORN. The federally owned properties could help ease the desperate housing crunch, she says, but the RTC has shown little interest in doing so.

ACORN, among the most active groups negotiating with the RTC, sued the agency last August for failing to live up to its affordable housing mandate. The group encouraged Clark to take over an RTC house to call attention to the federal footdragging — a strategy ACORN has used successfully in other cities.

Sitting in the Pauline Street house last fall, Clark was upbeat. ACORN officials, who were handling the legal dealings on her behalf, told her that the RTC had agreed to “freeze” all sales on the house and 99 other properties nationwide.

As neighbors dropped by, hearty New Orleans coffee with chicory brewed on the stove. Everything seemed fine. Still, aware of the uncertainty surrounding her acquisition, Clark hedged her excitement at the prospect of taking title to her own home.

“There is always that shadow that lingers when you’re in negotiations,” she said. “You just don’t know what can happen.”

“Landlord State”

With the risk involved in squatting, and the glut of rental property around New Orleans, why not give renting another try? Clark has an answer for that: If she buys her own home from the RTC, it will be the first place she will not face the constant threat of eviction.

Sitting amid a clutter of nails, tools, and furniture, Clark recalled the renting nightmare that drove her to squatting. “Everybody in my particular apartment complex got along fine, and then they moved someone in there who would beat his wife to a pulp,” she remembered. “I was living right on the other side of the wall and would call and make complaints. Other neighbors would call, too, but the office didn’t care.”

When the man fired two shots at another neighbor, Clark called the Realtor and demanded action. She got it. The landlord evicted her, giving her five days to clear out of her apartment.

“I think I bucked the system too much,” she said. “I was making too much noise about things.”

When the landlord took Clark to look at another apartment, she couldn’t believe her eyes. “The ceiling had literally fallen down, the cabinets were hanging, the place smelt like urine, the carpets were filthy — and he still expected me to take it.”

Clark said such harsh treatment of renters is commonplace in New Orleans. “Renters don’t have any rights. This is a landlord’s state here; they have all the power. It’s sad how they shift poor people around.”

Clark said that she and her friends cannot buy their own homes because they don’t fit the profile that banks require when making loans. “You have to keep in mind that you are in the Deep South. The people in power here are white and they tend to get the better jobs. It’s hard. You don’t make the money you do in California, New York. It’s really hard to excel here and it’s frustrating.”

But Clark has not been discouraged. “If I get my foot through the door, it’s going to open doors for other people. Right now, a lot of people are afraid to take the chance.”

A Dream Deferred

In the end, however, Clark’s dream of owning the Pauline Street house proved short-lived. In early February, she learned that the RTC had decided to give the house to another low-income family. The agency evicted Clark, ordering her to clear out of the home she had made for herself. “I’m losing this place for good,” she said. “It’s so disappointing.”

To add insult to injury, Clark said, ACORN officials had not called for weeks or offered to help her move. “I feel like ACORN didn’t do its homework. They told me that everything was on track, that they had an agreement with the RTC. I assumed they were doing all the paperwork and had a written contract, and now I find out it was only a verbal agreement.”

Beth Butler of ACORN said she was shocked that the RTC went back on its word. “A verbal agreement is binding in Louisiana. It was just unbelievable to us that RTC would sell the house to someone else, after the national officials had promised to freeze sales on that property.” ACORN is trying to find another RTC house for Clark and has asked the agency to reimburse her for the time and materials she put into the property.

Muriel Watkins, coordinator of affordable housing for the RTC, said it turned out that the agency had received a bid on the Pauline Street house before it formally froze sales. “We want to provide low-income housing to people,” Watkins insisted, saying the agency is working with ACORN to identify low-income buyers. The Pauline Street house, she added, is only “one property relative to all the properties ACORN is getting.”

But to Myrtis Clark, the house on Pauline Street was more than one property — it was the chance to obtain her own home, and to reclaim a community asset. The obstacles she faced reflect the bureaucratic nightmare many low-income people confront in trying to buy affordable housing from the RTC. The nationwide cost of the agency’s failure, like the cost of the S&L debacle itself, is borne disproportionately by the poor and middle-class, by people like Myrtis Clark — the millions of Americans for whom buying or renting a decent home is a fast-disappearing dream.

SIDEBAR

Where the Heart Isn’t

Although thousands of Louisianans qualify for low-cost homes under the affordable housing program mandated by Congress, only a few low-income families have managed to buy homes from the RTC.

A year and a half after the RTC was created, the agency has sold only 114 single-family homes under the program in the entire state of Louisiana. Worse, a total of 759 Louisiana properties set aside for working families may soon be sold to wealthy investors and speculators. Low-income buyers and housing agencies have been given a three-month “right of first refusal” on the homes as required by law, leaving the properties up for grabs.

Why has the RTC sold less than 15 percent of its affordable houses in Louisiana to eligible buyers? “I can’t give a concise answer,” says Garey Trahan, an RTC official in Baton Rouge. “It’s probably a combination of things: the poor condition of the properties, the soft economy, and the fact that there are few low-income purchasers on the property market. You have to remember, 70 percent of New Orleans residents are renters.”

Trahan concedes, however, that the agency’s small staff limits its outreach to low-income buyers. “I am the affordable housing program in two states,” he says.

A more serious problem, say housing advocates, is that the RTC has failed to provide the special discounts and financing that it gives to banks and big investors. Recognizing this, several agencies in other states are working with the RTC to create a program in which poor and moderate-income people could purchase RTC homes without having to make a large down payment — exactly the kind of plan advocates say is needed in Louisiana.

“The RTC has to be more flexible,” says William Quigley, a New Orleans civil rights lawyer. “In this town, poor people are very poor. Why not show them just a little of the flexibility the RTC is showing everyone else?”

Some non-profit groups think things are improving. The RTC has given property to non-profits in Texas and Arkansas, and the director of one neighborhood group under contract with the RTC praises its “wonderful working relationship” with the agency.

But many groups say the RTC has been absurdly slow getting information about available properties to prospective buyers. “Last fall, when I asked the RTC for a list of affordable housing properties in Baton Rouge, the office said it could not supply one, or for any other place in the state,” says Allison Kendrick, president of the Louisiana Housing Finance Agency. “To the RTC, the affordable housing program has just not been a priority.”

Lonie and Frenzella Johnson of New Orleans found out just how low a priority affordable housing is at the RTC when they tried to buy back their own home from the bailout agency last year. The couple bought their Mazant Street house in a black working-class neighborhood in 1971. They never missed a payment, and had almost paid off their mortgage when they decided to take out a second loan from local South Savings and Loan in 1985.

Then back surgery forced Frenzella to quit her job as a proofreader, and the family was forced into bankruptcy. Standing on the courthouse steps last spring, Mrs. Johnson watched, grieving, as South Savings took title to the family home at a foreclosure auction.

Ironically, South Savings itself went bankrupt, and wound up in the hands of the RTC. The Johnsons hoped to repurchase their home from the agency, and made repeated calls to South Savings to arrange the sale. Their calls went unanswered.

Then one day last summer, Frenzella, a volunteer with ACORN, was inspecting a list of RTC properties up for sale when she ran across something unexpected: the address of her own home. It was the first time she had any idea that the RTC might sell the house to someone else.

“I felt sick, disgusted, stunned, humiliated more than anything in this world,” she recalls. “When I first saw it, I couldn’t even talk.”

Afraid they would lose their home, the Johnsons made a formal $1000 bid on the house through ACORN. The community group faxed the offer to the RTC on August 18. And that, says Frenzella, “is when all hell broke loose.”

Several days later a local real estate agent stopped by the house to tell the Johnsons their bid would not be accepted. Then, on September 4, the Johnsons found an eviction notice nailed to their door. South Savings refused to accept their rent check, and the RTC never acknowledged their bid on the house.

The Johnson family, which includes an ailing grandparent, two children, and a grandchild, has moved several blocks away. The Mazant Street home now stands empty, boarded-up, its back door and metal downspouts already torn off by thieves.

“This was a nightmare for me,” says Frenzella. “I may look okay on the outside, but it’s eating me up inside.” South Savings referred all questions to the RTC, which did not respond by deadline.

Critics say that what happened to the Johnsons reflects the RTC’s lack of sympathy for the very people it is mandated to serve. “This family had almost paid off their home, and now they can’t even rent it,” says William Quigley, the attorney for the Johnsons. “It’s the great American dream in reverse.”

— K.W.

Tags

Katrina Willis

Katrina Willis, a financial reporter, visited New Orleans while an associate of the Center for Investigative Reporting in San Francisco. (1991)