This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 1, "The Golden Child." Find more from that issue here.

I lived with my wife and daughter in Macon, Georgia for three years during the mid-1980s, and one reason we selected the town for my wife’s medical residency was the presence of the Macon Pirates, a South Atlantic League baseball club. The doctor was soon working the insane hours of a resident, leaving my daughter and me alone most evenings, so we went to the ball games, for hot dogs and entertainment.

We attended over 50 games in a single season, and one clear memory from that time is of my three-year-old crying bitterly over a rainout. The society of chalk miners, cigarette factory workers, drunks, foresters, morticians, and railroaders which we enjoyed at Luther Williams Field was as fine as I have known anywhere. That same kinship can be enjoyed every season in Asheville, or Chattanooga, or Birmingham, or Savannah, or Jacksonville, or hundreds of other parks.

Most minor league towns have histories of organized baseball dating back to the early years of this century. Each town has seen the passing of some legendary player in the lore of the game — if not on the hometeam, then perhaps as an opponent or as a visitor when a major league club played an exhibition. Macon’s big star had been Pete Rose, who spent a season there in the 1960s. Augusta, where the Macon club recently relocated, was where another famous player, Ty Cobb, got his start.

Rose and Cobb shared more than their minor-league origins in Georgia. The similarities between the two men are striking, and a brief look at their careers provides some insight into the troubles in baseball today — and unveils the monopoly power that increasingly dominates every aspect of the national game.

Rose and Cobb collected more base hits than any other players in the game. Both played aggressively, gained fame with a single team, then managed that club after retiring from regular play. And both were embroiled in gambling scandals, although with dramatically different outcomes.

Working-Class Kid

Rose’s case is recent news. He has just served time in a federal prison for failing to report gambling income. Prior to his tax difficulty he was banned from baseball for conduct the baseball commissioner found to be “not in the best interests of the game.” The common understanding of that euphemism, based on accusations prior to the ban, was that Rose had bet on ball games, including those of his own club, the Cincinnati Reds.

In 1989, A. Bartlett Giamatti had just succeeded Peter Uberroth as Commissioner of Baseball. The former president of Yale University, Giamatti enjoyed extraordinarily good press. Having a certifiable intellectual at the head of the game seemed to improve baseball’s tone in the eyes of sportswriters, who hailed Giamatti as the “thinking man’s ballfan.”

Rose, on the other hand, was under attack by the press from the start for his smartass attitude, spiky hairstyle, and unsavory associates. After all, a mill worker’s son accused of gambling by drug dealers, race track touts, and petty criminals is not going to look good up against an Ivy Leaguer — at least not in the “Gold Card” America of Ronald Reagan and George Bush.

In short, Rose had an image problem, despite his unarguable skills in the game. A working-class kid from Cincinnati, Rose had always shown a tough exterior: when he tied, but failed to break the National League record for hits in consecutive games, he was asked to comment on his failure. “At least I won’t have to put up with you assholes any more,” Rose confided to reporters on national television.

It didn’t help Rose’s image when some of his supposed friends accused him of betting on ball games, hoping to win lenient sentences for themselves in drug and gambling prosecutions. Giamatti launched an investigation, and Rose responded with an aggressive stance reminiscent of his days at the plate. He hired excellent lawyers, including Watergate counsel Sam Dash, and mounted an unexpectedly shrewd attack on the commissioner. Rose challenged the National Agreement — the contract that gives the owners complete control over where players are assigned and sets strict rules of behavior that all players must follow. In effect, Rose was saying that whether or not he had gambled was irrelevant if he had been forced to agree not to gamble as a condition for playing baseball.

The Lords of Baseball seemed to jerk with the awareness that there was suddenly more at stake than the reputation of a single ballplayer. At risk was their control over players’ contracts, hence their monopoly power over the game — a power which television revenues have rendered more valuable than ever.

Baseball Czar

Rose’s case against the owners made me think of Ty Cobb, the Georgia-born player who had also been accused of betting on his own ball club by the commissioner. Indeed, the Office of the Commissioner owes its very existence to gambling. Before 1920 baseball was controlled by the presidents of the rival National and American leagues, feudal chiefs who presided over warring groups of team owners united only by the threat of would-be rivals trying to start a third major league. When an attempt to fix the 1919 World Series threatened to turn public opinion against the game, the owners acted swiftly to hire a “czar” with absolute power over the game. They chose Kennesaw Mountain Landis, a Chicago judge, as the first Commissioner of Baseball.

A Republican appointee to the federal bench, Landis never attended law school, but the baseball owners admired the numerous anti-strike injunctions he had issued from the bench on behalf of large financial interests. They were not disappointed. The dapper, pint-sized autocrat brought his anti-labor sentiments to baseball, promptly throwing eight players out of the game for life for gambling on the Series. He exacted no penalties on any of the owners.

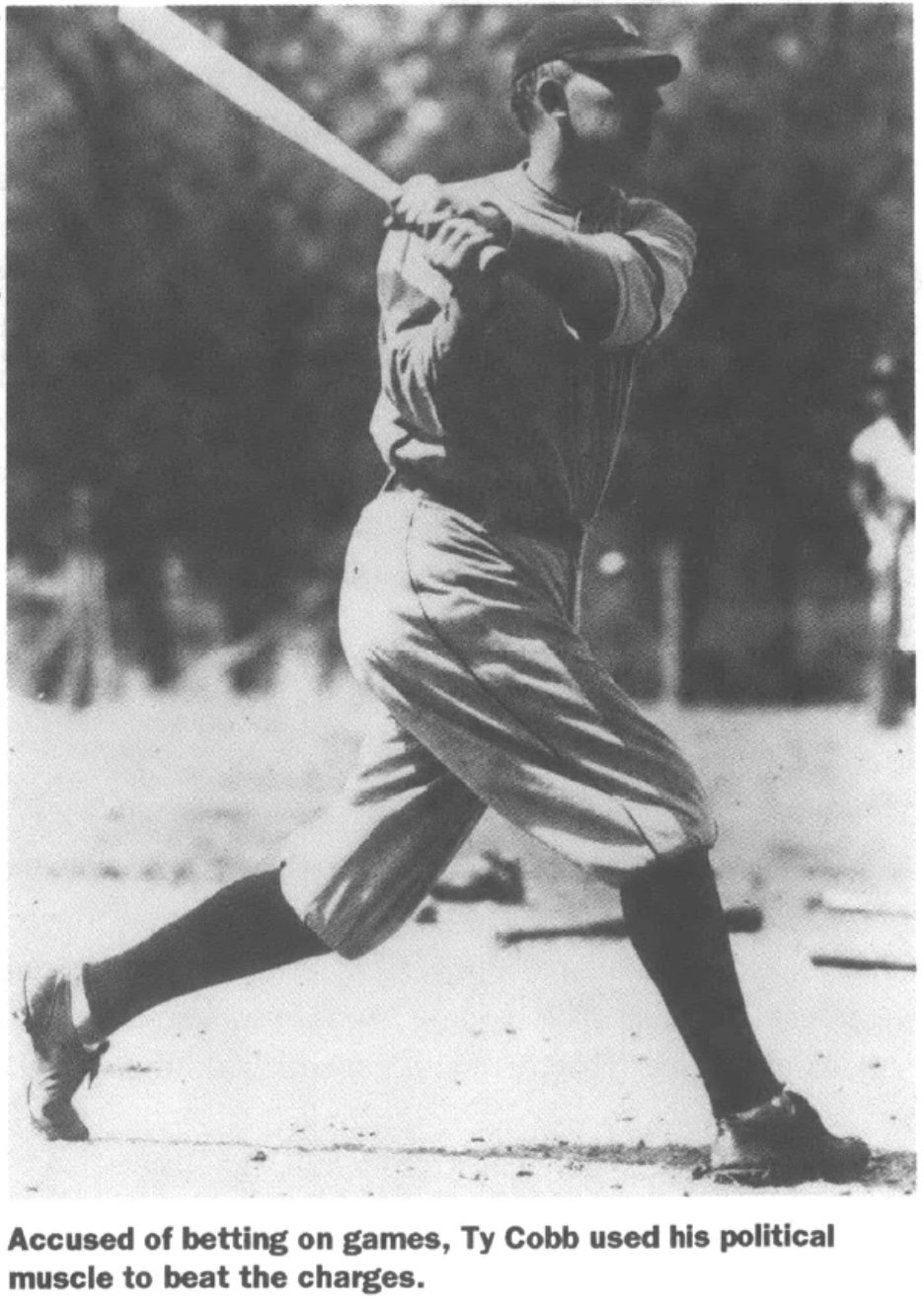

In the early 1920s, Landis heard charges that Cobb, then the manager of the Detroit club, had bet on opposing teams and then thrown games in order to win his wagers. Landis summoned Cobb to an interview, but the fiery manager struck back. Unlike Rose, Cobb was well-connected politically, and he used that influence against Landis. Both U.S. Senators from Georgia announced that they were disturbed by the economic monopoly of major league baseball and that they thought it warranted a Congressional investigation. Landis quickly abandoned his case. Tough on labor unions and illiterate ballplayers like Joe Jackson, Landis was not so bold when the owners’ monopoly — the source of his own power — was placed on the table.

That monopoly — which lies at the very heart of baseball’s economics — was made possible by the National Agreement. Signed as a peace treaty to stop the two big leagues from raiding each other for players, the Agreement created a “reserve clause” in player contracts that “reserves” the right of player assignment to the team owners. Although the clause has been modified to allow certain players to act as “free agents” and choose their own clubs, those rights can be, and have been, subverted by collusion among the owners.

Cobb mounted a political challenge to this monopoly through Congress, and Rose commenced a legal attack through the courts. In effect, both were suggesting that the National Agreement is a “combination in restraint of trade” prohibited by the Sherman Antitrust Act, and that any contracts made under such an illegal combination are invalid since they are inherently coercive. Anyone wishing to play baseball must sign the Agreement, since the owners enjoy a monopoly on major league play.

Sportswriters, oriented to spectacle, failed to understand Rose’s legal strategy, and the issue was entirely ignored by the business press, which has forgotten even the concept of antitrust law during the past decade and a half of deregulation. Baseball owners, however, seem to have understood the issue quite well, and pressured Rose to quit the game. That pressure was intensified by his looming prosecution for income tax evasion, for which he was jailed.

Having moved from Macon to a small town an hour and a half from the nearest ballpark, I have become a devoted fan of baseball on the radio, the medium best suited to the game. One night last year, as I drove home from a Savannah Cardinals game with my daughter, I listened to Rose on WLW, the Red’s hometown station, as he recounted his surrender to the commissioner.

His relief was palpable, even as it faded in and out over the airwaves. Rose had jumped at a settlement offer, pleading guilty to a minor offense, rather than attack the firmament of the institution to which he had devoted his adult life. That he got the chance to settle was testimony to the power of his bargaining position. Rose, a man with a teenage punk’s social skills, knew his strength instinctively. On the radio that night, he recited each of the more important charges made against him by the Commissioner, then exulted, “He didn’t get me for that one! ” He sounded like a youthful offender who had copped a plea to a lesser charge in the principal’s office, even though the plea meant he would be expelled from school for life.

MINOR-LEAGUE MONEY

Commissioner Giamatti died soon after the resolution of the Rose case, and some sportswriters blamed his passing in part on the hapless Rose. But the owners had survived, and having disposed of one troublesome employee, they immediately turned their attention to other labor issues.

In contract talks before the 1990 season, the Players’ Association accused the owners of conspiring to subvert their union contract by secretly agreeing not to hire free agents. The owners responded by launching a class war, locking players out of the ballparks and delaying the start of the season. But taking on the union proved tougher than banning a single player from the game, and an arbitrator ruled in favor of the players. It was somehow appropriate that such a troubled season should end in a World Series unpredictably won by the Reds — yes, Rose’s team, members of which gave him credit for their success.

Following the fight with their employees, the owners turned on their minor league affiliates. Over the years, an arrangement has evolved between the majors and minors in which the major league clubs provide players to minor league operators and pay their salaries. The minor league clubs then house the players, provide a ballpark, belong to a league of similar contractors, and make money (they hope) by selling tickets, concessions, and advertising.

In recent years, however, minor league operators have been able to turn quicker profits by selling their franchises (the Birmingham, Alabama club went to a Japanese interest). Like a lot of other properties in the overheated economy of the 1980s, minor league franchises have dramatically increased in speculative value. The major league owners decided they should cash in on the minor league boom.

Following their historic preference for an “all-or-nothing” method of negotiation, the owners threatened to wreck the game unless they got a bigger cut of the minor league action. They promised to create an entirely new minor league structure to compete with the existing clubs, which would be stripped of their players. To render the threat real, the majors bolted from the 1990 winter meetings in Los Angeles and conducted a rump of their own in Chicago.

The players are familiar with this strategy, and are not so easily cowed by it, but the minor league operators can boast no such experience. After brief resistance, the minors surrendered. Monopoly power is real power. The majors got the minor-league share of the television money, forced the small clubs to pay more of the player expenses, and tightened their control over how players are managed.

Baseball Bailout?

Such cut-throat business deals will mean little to those of us sitting in the stands watching the action this spring. The game’s great strength remains its appeal as sport, as play. My daughter and I, joined by a new baby sister, will be back in Macon on opening day this season. The Atlanta Braves have moved a minor league club to Luther Williams Field, remodeled after three seasons without baseball. We won’t worry overmuch about who is getting how much money out of our fun once the pitcher starts to throw. But this momentary unconcern is akin to the apathy drivers feel on the highway, even when they know the road was built by contractors who rigged bids and paid off politicians: Using the road does not imply any approval as to how it got there.

Baseball has long been a matter of money, but that aspect of the game is coming more and more to dominate every aspect of its character. While sportswriters keep the public whipped up about player salaries, the big money — from television and ever-soaring ticket prices — has continued to go to the owners, who are now so embarrassed by riches that they can’t even juggle losses out of their books.

Perhaps the economic hard times just now settling some of the looser accounts of the 1980s will have an effect on baseball as well. After all, deregulation is no longer regarded as an unqualified success. As one of the oldest deregulated businesses, baseball may come to mirror industries that have more recently abandoned antitrust protections — like the bus lines, the airlines, the savings and loans, and the banks and insurance companies.