Short Stories and Tall Tales

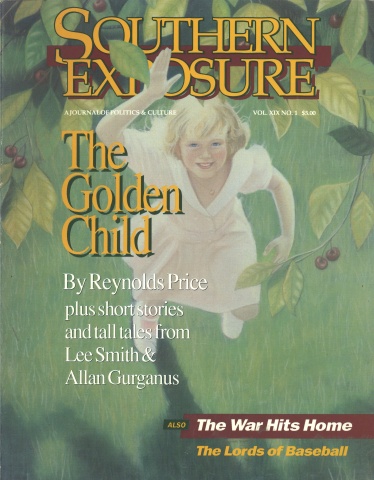

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 1, "The Golden Child." Find more from that issue here.

All too often, fiction written about the American South by Southerners has been lumped together as one large stewpot of turgid romance and “local color” — a strange brew of moonlight, magnolias, and collards. It is as if we must expect to endure the nightmarish specter of repeated sequels to Gone With the Wind and Tobacco Road with each newly printed page. According to novelist Pat Conroy, his mother once reduced all Southern literature to a variation on a single story: “On the night the hogs ate Willie, Mama died when she heard what Papa did with sister.”

Such formulations tend to dismiss Southern literature and its creators as “regionalist,” as if to suggest a narrowness of vision, a lack of “universality” of experience. “If you are a Southern writer,” Flannery O’Conner said, “that label, and all the misconceptions that go with it, is pasted on you at once, and you are left to get it off as best you can.”

Yet it remains inescapably true that this region, more than any other in the country, has produced modem writers of unusual depth and talent, whose individual visions have spoken for entire generations of Americans, whose consistently outstanding achievement has received recognition worldwide. Nobel Laureate William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Robert Penn Warren, Katherine Anne Porter, and others wrote extraordinary fiction in what came to be known as the “Southern Renascence” of the 1930s and ’40s. After them came Flannery O’Connor, Elizabeth Spencer, Reynolds Price, William Styron, Ernest Gaines, and Walker Percy, writers of remarkable power and range.

Today, the South is still producing immensely talented writers at an astonishing rate — Jill McCorkle, Larry Brown, Alice Walker, Tim McLaurin, Kaye Gibbons, Dennis Covington, Clyde Edgerton, Harry Crews, Cormac McCarthy, and Dori Sanders, to name but a few. It’s as if there were something in the water or fertile ground that continually nurtures and sprouts these storytellers, that compels them to speak.

The diversity and vitality of Southern fiction spring from the traditions of the region itself — a strong sense of place, both geographical and spiritual; an age-old respect for storytelling, a love of metaphoric and colorful language, a singular appreciation of humor and wit; a preoccupation with the past, both personal and regional; a strong identification with community and family; a keen knowledge that violence, oppression, guilt, and pride command a significant part of the individual and collective psyche.

These traditions comprise a rich inheritance for modem Southern writers. Storytellers in the region draw upon great resources from their own experiences in their families, from stories and myths handed down through generations. Mingling fact, fantasy, memory, and desire, they create unforgettable stories about people who actually lived — and about fictional characters who come to life through the telling. Southern storytellers take the tales they hear from childhood on — overheard from the back seat of the car, in the grocery line, in the church parking lot, at the end of the tobacco row, at the fire station — and through their imaginations and keen observation of everyday events, they transform them into fiction with the power to reveal and to alter the course of our lives. As Eudora Welty observed in The Optimist’s Daughter, it is memory and its attendant grief and yearning, not the literal past, that forever haunts us. “It will come back in its wounds from across the world,” Welty writes, “calling us by our names and demanding its rightful tears.”

In recent years, as the region has become less distinct, some say this inheritance is in danger of being obscured or lost altogether. With its bleak proliferation of shopping malls and mobile homes, fast food franchises and high-tech office buildings, the modem Southern landscape has begun to look like any other. With the impact of television and interstates, the Southern rural life of distinct, tightly knit communities is in peril.

But as the region has become more assimilated into the country as a whole, Southern writers have continued to grapple with the vexing character of the region they have inherited. For writers growing up in the South today, the region is still an ultimately confounding place. On the one hand, its communities nurtured them, providing close ties to neighbors, to church, and to agrarian traditions of reverence for family and fierce identification with local history. Relatively removed from mainstream industrialization, communities encouraged a love of storytelling, family mythmaking, and home-grown music and dance.

On the other hand, immersion in such strong cultural currents is not without its price. For thoughtful Southerners, the region’s history of oppression, violence, poverty, and racism cannot be rationalized away. Nor can the region’s extremes in religious fervor and politics be long ignored. Such intense contradictions in culture and upbringing demand a deep attention, require a painful struggle for identity. One simply must come to terms with the past, both personally and culturally. “The writer’s attempt to understand the region,” publisher Louis D. Rubin Jr. has written, “is an attempt to understand oneself.”

As Ben Forkner and Patrick Samway point out in Stories of the Modern South, Southern writers have a need to write, to describe the world in which they live, “a world of change and contradiction — the slowly embroidered, front-porch legends of The War suddenly juxtaposed with the hurried forward march of the Chambers of Commerce, and all this under the deep shadow of racial discrimination.”

The anguished relationship of Southern writers to their past and present has yielded distinctive, powerful, unforgettable fiction, as rich and varied as the many subcultures that make up the South itself. Like Southern music — which ranges from New Orleans jazz to old-timey mountain fiddle tunes, from cajun zydeco to urban rhythm and blues, from Mississippi Delta blues to gospel and bluegrass — Southern fiction is gloriously diverse and unpredictable.

The stories that appear in this special section of Southern Exposure reflect a deep appreciation for the past — and the ways it continues to haunt and enliven the present. Nanci Kincaid explores the subtle, yet forceful strictures and mores of race in a small Alabama town through the eyes of its children, both white and black. Lee Smith gives us the clear, unmistakable voice of a bitter mountain woman who reveals more than she realizes about the timeless themes of passion, jealousy, and loss. Tom Bailey examines one man’s futile efforts to overcome enormous, yet subterranean barriers created by his own fears and obsessions. Ron Rash speaks quietly of two young men’s search for dignity amid a growing awareness that their destinies are shaped by invisible shields of class. Reynolds Price weaves memory and imagination together, transforming history into myth to create, as he puts it, a “coherent story that is at once both fiction and confession.” And in a delightful essay on the origins of his own fiction, Allan Gurganus ponders the sometimes intractable nature of “true” stories in an anecdote handed down to him from his great grandfather and given renewed liveliness over generations through embellishment and repetition.

The only problem (if it can be called that) that we experienced in selecting stories for this section was an almost overwhelming wealth of creative work to choose from. What this special section came to be about, then, is celebration — of the diversity, strength, endurance, and triumph of Southern voices today. In this culture of transition and seemingly inevitable homogenization, these fictional voices remain genuine, arresting, and true, as unexpected and engaging as the region itself.

Tags

Susan Ketchin

Fiction Editor (1991)