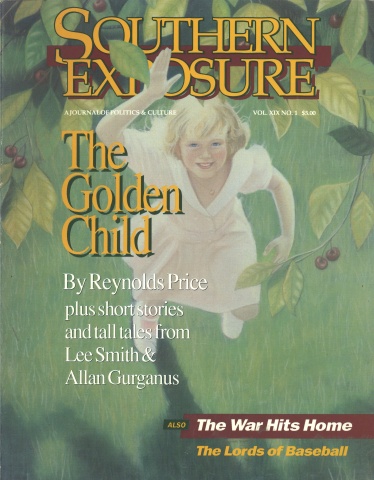

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 1, "The Golden Child." Find more from that issue here.

I never did know what ailed Nonnie. Don’t know to this day! But she had ever chance for happiness, ever chance in the world mind you, which it is not given to all of us to have, and stomped ever one of them chances down in the dirt like a bug. It seemed that Nonnie was bent on destruction, from the womb.

Why, the very first thing she ever done was kill Mama!

I will not forget that night as long as ever I live. It was a cold snowy night in the middle of wintertime. Old Granny Horn had been with us going on a week, Daddy had went up her holler to fetch her when it commenced snowing to where you could not even see the boxwood bush by the front steps, nor that big huge rock there by the gate, nor yet the gate itself nor the fence neither, the snow had blowed hither and yon to where it had covered up what ought to have been, and made new hills and valleys all around.

I stood on the porch looking out, as I recall, while Mama moaned inside of the house and Daddy chopped wood out back even though it was the middle of the night. Granny Horn had sent him out there finely, she said he was naught but a bother in the house. I stood still on the porch and looked out at the snow.

It was a new world out there! I didn’t know nothing I saw. And white — Lord, it was white! So white it stayed kindly light all night long, and all the shadders was blue. It was scary. It would be days and days before a soul could get in or out through Flat Gap.

And I looked at that snow and felt glad for all them mason jars of tomaters and applesauce and greens and such as that which me and Mama had put up last summer, and for the sweet taters down in the grabbling hole under the porch, and for the shucky-bean leather britches hanging up in the rafters over the loft, and the chest full of cornmeal—cornmeal enough to last till the baby is toothing, Mama had said.

The first time I heerd about this baby was back last summer when Mama and me was out in the yard putting up butter beans. We had boiled the jars and lined them out in the sun, and the sun looked real pretty shining off of them. Mama stirred the butterbeans with a wooden paddle and wiped at her face with her apron.

Honey you don’t have to stay out here and help me, she said. You can go over and play with Mickey if you’ve got a mind to.

No Mama, I said then. I like to help you. And it was true. For I was the best little girl! And I loved nothing more than helping my Mama, her voice was a song in my ears.

Zinnia, she said that day, straightening up, now I have some news for you. Come wintertime, we will have a baby in this house.

Where are we going to get it? I asked, for I did not know. I had heerd that you found them under a cabbage leaf, or that a great owl brung them.

Mama smiled real nice and stroked my hair. God will bring it, she said, and so I didn’t think nothing of it when she growed so fat and got so tired, not until this neighbor girl come up and told me after meeting that the baby was in Mama’s fat stomach, and then I hated the baby, for it had made my sweet Mama grow so big and sick, she wouldn’t hardly play with me no more, and she cried all the time.

I had heerd her crying at night and saying No Claude and They is something the matter and such as that. He said, It is God’s will, Effie, which is just like him, he bowed always to the will of God.

And Mama bowed always to Daddy’s will, which is how the Bible says it should be. In fact the only time I ever recall Mama acting any way but dutiful was when that baby was in her, and I say it was all due to the nature of the baby. For Nonnie had a troublesome nature from a child.

Things was never the same after that day we were out front canning, so that as I stood on the porch that winter night six months later and heerd Mama screaming out in the house behind me, I was not surprised to look out and see the world all different, all changed before my eyes, nor to feel the wind blow offen the snow and chill me to the bone.

Granny Horn would say something, and then Mama would scream, and then Granny would say something else, and then Mama would scream again. Out back I heerd Daddy, CHOP CHOP CHOP. I went back through the breezeway to see him. Daddy, I said. Daddy. But I couldn’t see nothing out there but his big dark form in the pale blue light. I could see it when he raised the ax, black against the snow. I heerd it when he brung it down. CHOP. CHOP. CHOP.

Daddy, I said, but he kept right on. CHOP. CHOP. CHOP. I stood out there wrapped up in a coverlet, hugging myself. Wasn’t nobody else going to hug me, that was for sure! They was all too busy borning the baby to care about me.

And yet I had done all the work, for Granny Horn had said her old self was wore out, and axed me would I be her extry hands, and like a fool I said yes, so she had set me to fetching and carrying for her, what all she needed—the scissors, the string, the borning cloths, water a-boiling in the big black pot. While I done all this, Mama just laid up in the bed staring out over her great stomach at me with her dark eyes real big in her thin face.

Now come here Zinnia, she said. This was right before the sun went down. And I went over there, and Mama smoothed back my hair and touched the mark on my face real gentle, the way she always done, and pulled me down to her, and kissed me.

Now you be a good girl, Mama said, and so I was, and did not cry.

But it galled me standing out there in the freezing cold in the middle of the night, why I could of froze to death for all they knowed, or cared! I was just a little girl. Too little to see what happened next, which was awful.

Claude, Granny Horn called out real sharp. Claude.

I ran back to the edge of the breezeway. Daddy, I hollered. Granny Horn wants you. I hollered out many times before he come, and even then he said nothing to me, but pushed me out of the way as he passed by. Now this was not like Daddy, but the Devil was in the house that night and had got into Daddy so it was not his fault.

I follered him in the open door.

Firelight was jumping everywhere. Mama was supposed to be laying on the borning quilt but she had kicked it ever whichaway and wadded it all up, she was thrashing so. Her long black hair streamed all across the bed tick and her shift was jerked up so her big white belly and her private parts were visible. Granny Horn was a huge old woman, as big as any man, but it was plain to see that even she was having trouble keeping Mama on the bed. Mama’s eyes was rolled back in her head and her hands was just clutching at everything, and you could not understand a word she said.

Now this awful sight did not jibe with my sweet Mama, you can be sure. I knowed she would be terrible ashamed to act so. I mean, iffen she was in her natural mind a course, which she was not. For Mama was a God-fearing woman with the nicest, quietest way about her as a rule.

Claude, bile me a good knife, Granny Horn said.

Daddy made this awful noise in his throat.

Go on now, Granny Horn said. Time’s a-wasting. This is a britches-baby, she said. Hit aint going to come by hitself.

Now I did not know what that meant, and didn’t nobody tell me neither. I sat down in my little canebottom chair and waited to see what would happen. I looked at the fan pattern quilt on my own little bed tick, at the snow out the open door, at the leaping fire. I looked everyplace but at my mama.

Now you hold her. Hold her shoulders down, Granny Horn said in a loud voice to Daddy, who done it, and then I looked, but all I could see from where I sat was Granny Horn’s wide back as she leaned over Mama, and Mama’s skinny white legs poking out on either side.

Push, Effie. Push! Granny Horn hollered. I seen the flash of the knife in the firelight. Then Mama screamed out once, a high thin sound so pitiful it has stayed in my ears forever, and then blood was everplace, a river of blood it seemed like, soaking Granny Horn from the waist down and turning the borning quilt and bed tick red.

Lord God in Heaven, Granny Horn said, but she was not praying. She was grunting and heaving, pulling and pulling, and then I seed the flash of the knife again, in and out, in and out, and Granny helt up the baby, now this was Nonnie, by its feet. But it looked so awful, I didn’t have no sense that it was a baby. But Granny slapped it until it cried. Then she flung it down in the cradle that they had there, my cradle mind you that Daddy had made for me, and left it squalling while she worked on Mama, and this gone on all night, them packing ever cloth they could find in in there, and even using snow finely to try and stop the bleeding, but nothing worked.

Daylight come and the whole cabin was a wet bloody mess and Mama was going, she did not know us. The baby whined in its cradle but Mama did not appear to heed it. For a long time her hands was still clutching and clutching at the air, but then she stopped that. Her hands closed up, her fingers curled like fiddlehead ferns. Her eyes was wide and staring until Granny Horn closed them. Granny Horn stood up then, finely. I know she was six feet tall.

Claude, where isyer likker at? she said, but Daddy would not leave Mama, he was laid acrost her bosom weeping like a child.

Claude! Granny Horn said sharp. I’ll git it, I said then, for I knew where he kept it in the loft, and I clumb up there and found ajar and brung it down to her. Granny Horn took a big swig of it, it was white likker, and looked at me directly for the first time.

Honey you go and lay down now, she said, and I done it. No sooner did I hit the bed tick then I was fast asleep, the soundest sleep in the world I reckon, for I slept all that day until night again, and when I woke it was dark and the fire was going and Mama was not there, nor Daddy, and Granny Horn was cleaning with a great pot of water and the baby was crying hard. Granny Horn gave me some johnnycake then and said to eat it and then said to go back to bed, and I done so, and when I woke again it was morning, another day, and the sun was shining offen the snow all around, but it would be some several more days afore you could get in or out through the gap.

I do not remember these days too good, to tell the truth. They seem to me now as a blaze of light, sun offen the snow. I know what happened, though.

Granny Horn laid Mama out on a plank they rigged up in the springhouse, and we kept her there until it thawed enough to bury her. So Mama was laid out and froze, finely and fectually, in the springhouse.

When it got to where Granny Horn could get through the gap she done so, taking the baby, as Daddy would not leave Mama. She took the baby to a woman that had one, so it could get some titty, and while Nonnie was gone, I played like she had never been borned. I played like I was the baby.

Then Granny Horn came back, which I hated, for she was so big and rough, she was the furtherest thing in the world from my sweet mama.

Sometimes I would go out to the springhouse and see my mama, although they had said not to, but I had figgered out the latch and sometimes I’d steal out there, and talk to Mama laying on the plank. They had covered her face with a camphor rag which smelt terrible, in fact you could not stay in the springhouse long because of it, you’d start choking. Once I picked up Mama’s hand but it was so cold, I laid it back acrost her bosom where they’d had it.

I don’t have no memory now of exactly how long Mama stayed in the springhouse, but it was a good long while. I got used to having her there, in fact, and was sorry when it thawed enough to where the neighbor folks come up and they buried her.

Now Daddy acted awful all this while, he would not look at nobody, nor talk to them, and when the neighbor folks left, he would not talk to me either, not for the longest time. Then one time when I brung him some food, he said, Well, Zinnia, I reckon you will have to be the little wife around here now, and I said I would, and I have done for him the best I could, ever since. Nobody could have done better.

But now it seems to me that the one who is there all the time, the one who is cooking and mending and fetching water and just doing in general what needs to be done, well that one gets precious little attention. It is the squeaky wheel that gets the grease every time. And I have gotten mighty little appreciation over the years, all because of that hateful little Nonnie.

I say hateful. And she was hateful, but she had everybody else fooled but me. She had them all eating right out of her hand, by acting so sweet. I know acting when I see it. And I was the one that had to go around picking up after her and saying Did you eat yer supper Nonnie and Don’t play in the rain Nonnie and such as that.

For Nonnie was the silliest, mooniest child you ever saw, not one grain of sense in her head! She would of starved to death or killed herself a hundred times if it hadn’t of been for me. She would have killed herself over and over doing the crazy things she done, such as swinging on grapevines and playing with snakes. She never had a thought in the world for what might happen to her.

And was lazy to boot! If you asked her to churn, she might start out a-churning, then she’d be churning and singing, then she’d just be singing, and wander off singing, and allow the cream to clabber in the churn. Many’s the time she done that, and many’s the slap I give her for it. Oh I done my duty, rest assured of it, but I just couldn’t get through to her, so it done no good in the end. As a littlun, Nonnie was all the time a-singing, and different folkses would come by the house and learn her new songs, for she took to it so.

I could not carry a tune in a bucket myself, and don’t give a damn to. For, what good does it do you in the end? What good did it do Nonnie? As a girl, her favorite song was

The cuckoo she’s a pretty bird

She sings as she flies

She brings us glad tidings

And she tells us no lies.

She sucks all pretty flowers

To make her voice clear

And she never sings cuckoo

Till the spring of the year.

And to this day, that song reminds me of Nonnie and how silly she was. But Daddy was plumb fooled by her, and when she was little he used to carry her to town on the front of his saddle and then set her up on the counter in the store to sing to folks. Daddy never took me to town on his saddle, I might add. Of course I would not have cared to be displayed that away nohow, but you ought to treat children equal I say, and not favor one over the other so.

Well in all fairness, I know that Daddy did not favor Nonnie because of Nonnie her ownself. No, he favored Nonnie because she was the spitting image of Mama. Everybody said so. So it was not Nonnie’s fault, in a way, but she got spoiled rotten all the same. And she was not all that pretty neither, never mind what folks said. She was kind of dreamy and dish-faced if you ask me. Not to mention contrary. Now, we all know what a woman’s lot is, but Nonnie wouldn’t have no part of it! We’d be sitting by the fire of a night, for an instance, and I’d be doing piecework on my lap, but Nonnie she’d have flung herself flat down on the floor and be a-staring and a-staring into the fire, and not doing a blessed thing with her hands. When you’d call her, it was like she was off in the clouds someplace.

Nonnie, I said one time, then Nonnie real loud and sharp. Oh she looked up then.

Nonnie, what air ye a-looking at, anyway? I axed her, and do you know what she said? She said she’d seen figures a-dancing, dancing in the flames!

Of course later I remembered her answer real good, in light of the awful thing that would come to pass, but at the time it just hit me as more of her foolishness.

And as she got older, she got worser. She started in a-wanting to go to play-parties with the big gals and fellers when she was not but about twelve years old, just ragging Daddy to let her go, and of course he done it finely, for he always let Nonnie do exactly what she pleased.

Zinnia, you go with her and watch out for her, Daddy told me the first time he let her go, but I would not do it.

I don’t care to go, was all I said. Hadn’t Daddy seed that I hadn’t never gone to a play-party myself in all them years? For I am no fool. And I knowed them boys would pass me by, a-stepping Charley, and I refused pint-blank to give them the satisfaction.

I didn’t care for boys then, and I don’t care for men now. They are nothing but a vexation and a distraction, and can’t none of them hold a candle to Daddy anyhow.

But Nonnie, she’d go or die, and then she’d be mooning around over first one and then another. She used to sing this little song

Oh I wonder when I shall be married

Oh be married

Oh be married

Oh I wonder when I shall be married

Or am I beginning to fade?

It was the dumbest little song I ever heerd, and she was the dumbest little girl I ever saw to sing it, and I said so. Didn’t faze Nonnie, though. She’d swat away my words like they was flies.

And when we would go anyplace, if it was meeting or the store or anyplace at all, why she would flirt with the boys till it was shameful. But didn’t none of them come up here, for Daddy had said that they was not to, and most folks was kindly afeared of Daddy. Daddy thought none of them boys was good enough for our Nonnie, she had really pulled the wool over his eyes.

Anyway Zinnia must have a husband first, Daddy said at the table one night just to devil us, but I just laughed and said, The last thing in the world I need is a husband. I need a husband like I need a hole in the wall, I said. And whatever would you all do without me anyway, if I was to leave? I axed them, for we were eating supper which I had cooked, mind you. You-uns would starve to death, I said.

And do you know what Daddy done? Why he reached over acrost the table and took Nonnie’s hand. Why Nonnie will be the little housewife then, he said, grinning, he was just funning her because he would not have let me go for the world, mind you, but silly little Nonnie busted into tears and ran out of the house a-blubbering.

Oh I will never get married, she wailed. You all won’t let me, she wailed. If I have to wait for Zinnia I’ll be an old maid, she wailed out in the yard while Daddy and me sat on at the table and finished eating supper.

The truth of it was, Daddy wanted Nonnie to stay in school as long as ever she would, I believe he had kindly a hankering for Nonnie to make a teacher like one of Daddy’s aunts done, over in Tennessee. Oh, he wanted the world for our Nonnie! And she could of had it too, it was hers for the taking. And it was all right with me, mind you, for Nonnie to get all that schooling, as I couldn’t get nothing atall done with her mooning around underfoot day in and day out, I was plumb glad to see her go flouncing out that door to school. She used to ride her little pony down to the schoolhouse every day, this was a white pony that Daddy had bought for her over in Sparta, that she named Snowy. I had not took to school too good myself, truth to tell. It seemed like a waste of time to me. But Nonnie she liked it fine, and the schoolteacher, Mister Harkness, set a big store by her. She had him wrapped around her little finger too.

I recall one time when our preacher, Mister Cisco Estep, was questioning Daddy about Nonnie’s schooling and what did Daddy mean by it, for the Bible itself says that too many books is a sin.

I will not forget what Daddy answered him.

Cisco, he said, Nonnie is a soft girl, like her mother. I do not want her to get all wore out by hard work like her mother done. I feel real bad about her mother, Daddy said.

This is the only time I ever heerd Daddy say anything about Mama, or saw him look so mushy in the face.

I want Nonnie to have a better life, Daddy said.

But Nonnie, she didn’t care nothing about that, all she wanted was a feller. Nonnie was just a fool waiting to happen.

And one day sure enough she came back from going down into Cana with some of the neighbor people, looking like she had a fine mist of moondust laid all over her. Her black eyes was as shiny as coal.

Well, who is he? I axed straight away, for I knowed immediately what was up.

Nonnie would always answer you right back, and truthful too. She was too dumb to do otherwise. Oh Zinnia, she said, I was just standing in the road talking to some folks when this man rode in on a gray horse. He was a man that none of us had ever seed before, and not from around here. He is real different looking, real handsome, like a man in a song. Anyway, he looked at me good as he rode past, she said. I looked at him and he looked at me, Nonnie said all dreamy, and I said So? for this did not sound like much to me. Well then he got off and hitched the horse up at the rail there and come right over to where I was standing in the road talking to Missus Black, and he takes off his hat and kindly bows down like a prince, you never saw the beat of it. Then he says, What is yer name? and I told him, and Where do you live? And I told him that too.

Oh Nonnie, I said. He can’t come up here. You don t know a thing about him.

Nonnie flashed her eyes at me and bit her pouty lip. He has got some money from a previous venture, she said, real high falutin. And he aims to settle in these parts.

Well, sure enough, here he come, and sure enough, Daddy run him off. He met with the man, whose name was Jake Toney, in private afore he run him off. Nonnie sat on a chair out in the yard, just tapping her foot, while Daddy talked to Jake Toney. Then she saw fit to keep quiet for the length of time it took Jake Toney to get back on his gray horse and ride out of sight, but as soon as he was gone, she just throwed herself on Daddy like a wildcat from Hell, crying and clawing at his eyes and hitting at him, and Daddy just helt her out at arm’s length and let her fight till she either calmed down or wore out, one.

Now listen here, girls, he said, when Nonnie had finely quit fighting. That man there is a Melungeon, and he won’t be coming up here again. I knowed it as soon as I saw him, Daddy said.

A what? Nonnie said, and then Daddy told us about the Melungeons, that is a race of people which nobody knows where they came from, with real pale light eyes, and dark skin, and frizzy hair like sheep’s wool. Sure enough, this is what Jake Toney looked like all right.

Niggers won’t claim a Melungeon, Daddy told us. Injuns won’t claim them neither.

The Melungeon is alone in all the world, Daddy said, and at these words, Nonnie ran off crying. She was so spoilt by then, she couldn’t believe she couldn’t have anything she wanted.

Well, Nonnie cried for some several days after that, but then Daddy made her go back to school, and just about as soon as she started back, she cheered up considerable. In fact she cheered up too fast, and I don’t know, there was just something about her that made me feel funny, not funny ha-ha, but funny peculiar. They was something there that did not meet the eye. So one day when Nonnie rode off to school, I determined to ride over toward Cana myself, not an hour behind her. I told Daddy I was going to the store.

I can’t say that I was surprised when I come riding around the bend there where that little old falling-down cabin is, that used to belong to the widderwoman, and seed the gray horse and the little white pony hitched up in front of it. I got off my horse and tethered her back there in the woods and then walked kindly tippytoe over to the cabin, but I need not have gone to the trouble. For they were making the shamefullest, awfullest racket you ever heerd in there, laughing and giggling and moaning and crying out, and then he’d be breathing and groaning at the same time, and then he hollered out, and then she did.

School, my foot!

You had better believe I told our Daddy what was going on in that cabin!

So he was waiting on the front porch that afternoon when Nonnie came riding home on her little pony. He did not let on, though.

Evening, honey, Daddy says.

Evening, Daddy, says Nonnie as sweet as ever you please.

How was school? Daddy axed and Nonnie said, Fine, sir, and when he axed her what did they do today, why she commenced upon some big lie about geography, but before she got halfway done with it, Daddy had struck her on the shoulder with his riding crop, knocking her on the ground, and then he beat her acrost the back with it until she cried for mercy with her hands before her face. I did not lift a finger to help her neither, for she deserved it. Nor did I comfort Nonnie when she lay crying in the bed, not until way up in the night when finely I brung her some tea and some biscuit. Which she did not touch, hateful as ever.

And in the morning she was gone.

She had lit out in the dead of night on her pony, gone down to find her Melungeon at Mrs. Rice’s boardinghouse where he stayed, and I couldn’t tell you what passed betwixt the two of them when she got there, but the next day he was up and gone before daybreak, alone. And then what did that silly Nonnie do? Why, she locked herself up in Jake Toney’s room all broken-hearted, wouldn’t come out for nothing. Mrs. Rice had to send up to the house for me to come and get her.

Jake Toney left owing money all over town as it turned out, one jump ahead of the law. He owed a lot of people due to the poker game he had been running regular in the back of the livery stable. Mrs. Rice was fit to be tied, as he left owing her considerable, also old Baldy McClain that ran the livery stable and was supposed to have gotten a cut on the game.

They all liked to have died when they found out that Jake Toney was a Melungeon to boot, which I told Mrs. Rice first thing when I went down there to get Nonnie. Mrs. Rice’s jaw dropped down about a foot. The news was all over town inside of a hour.

As for our Nonnie, she was mighty pale and mighty quiet, riding home. For once she had nothing to say. She was not a bit like herself after that, and would not go back to school for love nor money, but stayed at home not doing a thing but crying and looking out at the mountains from time to time. This like to have killed Daddy, for deep down in secret, he is real soft-hearted. He brung Nonnie everything he could think of to cheer her up, including a silver hairbrush and a silk scarf.

Iffen I was to go offin the bushes with every Tom, Dick, and Harry that come along, I axed Daddy, do ye reckon I could get me one of them scarves?

Whereupon Nonnie turned right around and gave it to me, of all things! I was not too proud to take it neither. In fact I felt gratified to take it, after all the trouble she had put me to. For Nonnie owed me, and that’s a fact.

Well, we never seed hide nor hair of the Melungeon again, but Nonnie continued grieving him for months on end, and laying up in the bed all day long doing it. Then one day I looked at her good, and all of a sudden it come to me that she was going to have a baby.

No I aint, she lied to Daddy, flashing her eyes, but we sent for Granny Horn who found out the truth of it soon enough.

And then here comes Preacher Cisco Estep, hat in hand, a-knocking on the door.

I’ll tell you what’s the truth, he said to Daddy, when the two of them had set down. I would send her off someplace if hit was me.

But whar’d she go? She belongs here, Daddy said real pitiful. His eyes was all red from crying and staying up late.

Well now Claude, think about it, Preacher Estep said. If she tried to come to meeting in her condition and unwed, I’d be forced to church her, as ye know. And around here, everbody knows who she is and what she done, and won’t nobody take a Melungeon’s leavings around here neither, not to mention the child. This is the long and short of it, Preacher Estep said. But if she was to go somewheres else, say, she might have a chance for a new life. In fact, Preacher Estep said real forceful, In fact, Claude, I have got a proposition for you. Preacher Estep took out a hankerchief and wiped at his big red fleshy nose, that looks like a sweet tater.

Well what is it? Daddy said without no hope.

Well they is a man I heerd about at the past Association meeting that needs a wife the worst in the world, Preacher Cisco Estep said. He is in a fair way to come into quite a parcel of land over at Mossy Branch, what is now Preacher Stump’s place, but he don’t have no wife, nor no children to work it. He is a elder in the Chicken Rise Church too. So Preacher Stump has let it out to all and evry that he hisself aint long fer this world, and he would like to see this feller settled down regular on his land. Hit’s a nice piece of land, Preacher Estep said, and I don t believe this feller is too particular neither.

Daddy looked at him. You could tell he was considering it.

I wouldn’t see no reason to mention the Melungeon, Preacher Estep said.

Done, Daddy said.

And so this is how Nonnie come out smelling like a rose one more time, and got a great prize for being bad. For that land over at Mossy Branch turned out to be among the prettiest I have ever seed, and hit turned out to be a fine big double cabin over there — finer and bigger then our own, I might add — and I was further surprised to find out that Ezekiel Bailey hisself was not so bad to look at neither. He come out to the wagon grinning when we drove up, and he was just as nice to me as ever he was to that silly Nonnie who done nothing but cry and cry, and he did not even appear to notice my face none. I remarked upon how tight he helt my arm when he helped me down off the wagon, and how much he appeared to like the fried apple pies we had brung them — which I had made! — and I knowed in my heart of hearts that Ezekiel Bailey preferred me over Nonnie. Yet I resolved not to act on this, nor to tell no one, for I would not disappoint Daddy by leaving him, he needs me so.

Daddy said as much too when me and him was driving back through Flat Gap late that night after leaving Nonnie over on Mossy Branch with old bent-over Preacher Stump and Ezekiel Bailey her husband to be.

It was too dark for me to see good even though the stars was out, because of how the mountains rise up there directly in the gap. It was black as tar in the gap, but I could tell that Daddy was crying, and when he spoke, his voice was irregular. If I ever lay eyes on him again, I’ll kill him, Daddy said after a while, meaning the Melungeon. Then after another while, he said, Well, hit’s jest you and me now, aint it Zinnia girl? and so I took his old work-hard hand and helt it in mine, and so it has been ever since, just me and him, the way it ought to be, ever since that very night when we was riding home through Flat Gap in the pitch-black night, the night so dark I didn’t have no birthmark, and I was just as pretty as Nonnie.

Tags

Lee Smith

Lee Smith was born in Grundy, Virginia and lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She is the author of seven novels, including Oral History, Family Linen, and Fair and Tender Ladies, and two collections of stories. This story is excerpted from her novel-in-progress, This World Is Not My Home. (1991)