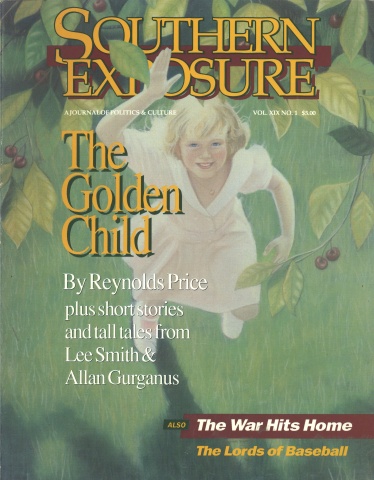

The Golden Child

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 1, "The Golden Child." Find more from that issue here.

If she were alive, she’d be sixty-seven. But she died at nine, in agony. And so while she lives in a few minds still, she lives by the name she was always called in family stories — Little Frances. The stories were few and remarkably sketchy, as if my endlessly tale-telling kin knew they must use her but could hardly bear to portray her fate on the bolt of wearable goods they wove from the lives of all our blood and neighbors.

We knew she was “both her parents’ eyeballs,” a local expression which meant “their all.” Her father was “Stooks” Rodwell, my mother’s youngest brother. Her mother was “Toots,” from Portsmouth, Virginia; and all their married life, the two lived there. By the time I knew them, Frances was dead; and they showed how badly scarred they were. Stooks was roughshod and raucous, the family cynic. Toots was acid and managerial, though both craved fun and were as loyal in trouble as good sheepdogs.

Before I was five, I knew nearly all I’d ever know about Frances. She was blond and fine to see. She fell while skating on the concrete sidewalk and scraped a leg. The scrape got infected but seemed to heal. Then a few weeks later she ran a high fever that wouldn’t break. The doctor diagnosed it as osteomyelitis, a deep bone infection. In 1931 there were literally no effective internal antibiotics. The only treatment was to scrape or saw out the affected bone, crippling the patient.

But with Frances’ fever, surgery was impossible. Infection roared through her. The relentless fever triggered convulsions. My mother told me more than once how “Little Frances’ head would bend right back and touch her heels — she spasmed that hard.” The child suffered dreadfully for several days. Her lips dried crusty, her voice went hoarse, but she still pled for mercy. Everybody hovered and prayed; nothing helped in the slightest but death. It came at last, though nobody left alive was the same ever again, not at the thought or mention of Frances — Little Frances, welcome as daylight, tortured to death as a lovable child.

When I was born two years later, it was touch-and-go from Mother’s slow labor well on into my third year. Inexplicable convulsions would seize me, a long spell of whooping cough, skin eruptions that left me bloody. No infant had died, in either of my parents’ families, in forty years. But the recent fact of Frances must have appalled them night after night, as they watched me suffer too, helpless and pleading. From the year I retain my first strong memories, between three and four, I can call back vivid pictures of her still. Mother had a hand-colored picture of her, framed on the bedroom dresser.

It’s a bright warm day. Little Frances stands outdoors in a pale dress, four-feet tall and half-turned away. But someone holding the camera calls her name; and she turns to look, turns forever in fact. Her blond curls reach almost to her neck and are blurred by the move. Her eyes are crouched against the sun, so I have no sense of their color or size. But her lips split open on a smile so strange that, even then, I guessed the smile was a clue to some big secret she kept. This girl, my tortured cousin, knew something big and kept it hid.

In a few more years, when I’d seen two or three old kinsmen’s bodies, dead and still and cold as dressed chickens, I thought I’d caught the heart of Frances’ secret. She knows she’ll never get old like this, this cold and smelling like celluloid. She’ll stay there smiling, in a handmade picture. But I took little comfort in my discovery. I still had most of childhood to travel before penicillin and sulfa drugs were widely sold; and Little Frances would be brought to me, again and again in Mother’s voice, at any chance of physical harm.

Touch football, running, sledding in snow, my first roller skates — as I left for every innocent game, Mother was liable to cloud and mutter “Little Frances would be here, strong today, if she hadn’t fallen and scraped her shin.” And I just now recall that, since Frances came from Mother’s family, her name was absent from my even-more-direful father’s warnings. With no such terror in his bloodline, and though a staunch Democrat, Father resorted to President Coolidge’s son, who blistered a heal at tennis and died of infection swiftly thereafter.

Yet for all the use of my dead first cousin as a somber omen, I never came to resent her name or to gloat in private on the early end of a family saint. I can no longer hope to explain my logic; but somewhere long before puberty, I told myself I loved my cousin Marcia so much I would marry her, down the road. I also guessed there was something skewed in the plan, some kink. I’d do my research in cool disguise, concealing my hope for Marcia under a different name. So one afternoon — age seven and back in the kitchen with Mother — I chose my best absent-minded voice and said “If Little Frances was living, and we loved each other, could we get married?”

Mother said “No.”

“Why?”

“She’d be your first cousin.” “What’s wrong with that?”

“Son, it’s against all kinds of laws. You might have two-headed babies or morons.”

“Why?”

“You just might. It works that way.” (We lived in medieval oblivion to sane genetics. Years after, when Mother was bearing my brother, a neighbor stopped by with a live lobster somebody had shipped him, on ice, from Maine. Lobsters were as rare in the South in the thirties as antibiotics; and when he was gone, my mother said “I hope this baby won’t come here wearing feelers and claws” — she was only half-joking.)

First cousins were out then, unless we eloped and deceived the Law. But there might be hope — Marcia and I were first cousins once-removed. I’d try that next. I started to say “What about once-removed?”

Mother’s eyes had filled though. She said “I think Little Frances loved me more than anybody else before you. I used to take her horseback riding, when she came down with Toots on the train.”

I’d never quite heard that before, how I had overtaken Frances in strength of love for someone as easy to love as my mother. It thrilled me right at the roots of my scalp because I loved her with a depth so dark it hurt more than not.

But before I could think of envy or pride or ask more questions, Mother painted one of her oldest pictures. “Little Frances walked down the aisle at my wedding, ahead of me, and scattered rose petals to guide my path. Toots had made her a dress with Belgian lace; and when I walked toward that altar behind her, I prayed to have a child that fine — she was five years old, smart and sweet as the day. I can see her hair right now, in candlelight.”

I said “Did you get it?”

“Get what?”

“A child,” I said, “that fine and smart.”

But though Mother often said God chose wisely in sending her a boy (she was half a boy herself, many ways), at that strange moment her tears poured free; and she left the room.

Her unpredictable bondage to the past, always a grim past, was one of the few sad facts about her — her parents had died long before she was grown, and she marked their birth-and death-days yearly with a taut brow and full eyes. But that one time stuck in my mind as the worst of all, the day she chose Little Frances over me. It became the day I began to cross the wide threshold that waits for us all; I began to see my own death, ahead.

At the moment I didn’t think to follow my mother and ask more questions, on Frances or me or the aim of life. Like most young children, I had mostly assumed the world was one enormous breast, full and generally trusty. Its purpose was feeding and caring for me. How had this dreadful door swung open — a good child wrenched into burning hoops; then dragged out of sight, in screams, forever. I almost certainly went to my room and played with my soothing menagerie of toys — elephants mostly, friends to man, but also a pride of treacherous cats.

And before many nights, I started the dream that rode my sleep for years to come. In the past I’d occasionally waked up scared from a nightmare and run to Mother and Father’s bed, my safest harbor. Hard as this new dream was, however, I kept it secret and paid the tolls it took on my peace. It sometimes changed the setting and lights, but it always told the same cruel story. I’m lying in bed or maybe outdoors in my new tent. Sometimes Marcia sleeps beside me; sometimes my black friend, John Arthur Bobbitt. But whoever's with me, they sleep on peaceful throughout my trial. What happens next is, I wake up suddenly in the dark and find I can’t move — not a muscle, a cell. I can’t even blink my open eyes. All I can do is somehow draw light shallow breaths. I tell myself I’m dead like Little Frances; and though I am scared and hate my stillness, I also think ‘Well, at least it didn’t hurt.’ Soon after that my backbone twitches, then spasms gently, then hard hard. My head and heels draw backward slowly toward each other. Then pain like nothing I’ve known or dreamed jolts through me like current. I understand that I’m not dead yet, but I cannot speak to ask for help or even for company. My partner, Marcia or black John Arthur, has not cared enough to wake and watch. This may not end. I wonder if Frances is trapped like this, or has she gone on somewhere free?

The dream came back maybe two dozen times throughout my childhood till I left home for college and the world. Then I thought it stopped. And I thought I knew why. My mother had died; nobody was left above ground, near me, who’d known my pitiful cousin and could bring her pain back toward me in words. Bad as it was, I went on keeping it secret from others because it gave me a serious size in my own mind. I would someday stop. Something was loose in the world, or inside me, that watched my moves and sooner or later would seize my legs and lay me down forever. From knowing of Frances Rodwell’s fate, I understood that much before I even started thinking of eternal life, much less hoping for it.

I was so lonely and my life was so calm, till I was near grown, that such a grim prospect was not unwelcome. It dramatized my days and nights, all the risks I took in playing alone. It illuminated the faces of friends I made at school. Each year I’d fix on some boy or girl, as if he or she were the light I needed to move and grow. But at some unpredictable point in my passion, the picture of Frances would stand beside them as an actual threat when I studied their eyes or the strength of their arms and envied their laughing ease, their power. Overnight they could be clawed down in pain and die with no rescue.

For instance, in the fourth grade I knew a chubby and very shy girl who would talk to no other boy but me. She was never a target of my adoration; but the spring we were ten, she suddenly died of diabetes. She got home from school one afternoon, while her parents were still at the hosiery mill; she lay down to take her usual rest on the living-room couch before putting on the potatoes for supper. But by the time her father walked in at half-past four and called her name, she had drifted off — so gently, he said, that “not one hair of her head was wrinkled.”

Mother and I went to pay our respects; and there she was — her name was Hallie — laid out in a short white coffin, dressed in white with a white carnation in her bloodless hand. No star in all the movies I’d seen held my eyes like Hallie. She seemed both stiller than any rock mountain and also trembling like a gram of radium, pouring out rays. I understood that her luck was awful; but I also envied the pale allure that drew us toward her and would keep this final sight of her face as clear as a stab, in our minds forever. I knew better than to say it to Mother. But standing there and later at the funeral, I more than half-planned a rival attraction — my own death soon.

And I almost got it. That same summer my family and I made a weekend trip to mine and Mother’s birthplace, the Rodwell home. Little Frances’ parents were there on a visit; and with all the joy my mother took in each of her kin, there was no way not to drive up there and see Stooks and Toots. Already I’d secretly turned against them. Stooks was loud and a mean joker. Toots was gentler but would still ask scalding questions in public, like “Don’t those knickers smell a lot like pee?” And the two together, once Frances was gone, had fallen deep in love with Marcia, my first cousin once-removed and Stooks’ great-niece. At the age I was, I could see no reason for their favoritism except that Marcia was a light-haired girl and was born nine months after Frances died (the fact that I too loved Marcia only raised the pitch of the tension I felt).

The first night there, the house was full of siblings, aunts, uncles and cousins. Marcia and Pat, her younger sister, and I had been shouldered out of the living room and were playing cards in the long dim hall. Our skills were limited so the game must have been either fish, slapjack or maybe old maid. Anyhow I recall I was cheating to win. Marcia and Pat were loudly complaining, though with no great rancor; they’d soon have curbed me back into line.

But Stooks, in the living room heard the debate and came out to check. He was always trying to barge in on us with rough dumb jokes to make us like him, when I understood that his principal aim was guarding Marcia from worldly harm. That night when he learned I’d cheated at cards, he lit into me with what I remember as unearned meanness — Who did I think I was, some prince? Didn’t I know a cheat was the lowest scoundrel on Earth? Who would ever love me? I’d better get myself honest, right now.

With the passion for justice and fine proportion that all children share, I knew he was way out of line and hateful. I also knew he was Mother’s brother, old and loud, and would get away with it. So I said not a word but fought back tears long enough to stand and retreat, by the dark back way, to the west bedroom where we would be sleeping and where I was born. For once I took a reckless course and shut the door behind me. I was truly alone now. That would show them.

Then in savage misery I fell face-down on my narrow birthbed and actively wished hard luck on Stooks. I waited long minutes for Mother to come and ease the pain, for anyone out of that crowd of laughers to take my side and stand for the right — it had just been a game. When nobody showed up and laughter continued elsewhere without me, I pulled my mind back into my skull and relied on me, my only friend. In fairly short order, I found two facts I’d ignored till then — that Frances died to punish her father and that I was glad. The truth was no more mysterious than that. And I said it over time and again with a merciless smile in the thick black air till I finally dozed.

What woke me, whenever, was a dry tap tap, hard and inhuman. I was not much braver than the average child, but at first I lay still and tested the sound. It was not the shut door, no knocking hand. It came from the far west side of the room, entirely dark. I’d already read Treasure Island and stored the news and sight of Blind Pew, tapping on the road with his walking stick and bent on vengeance. So at once I guessed this was no kind gift, aimed toward me in recompense for my mistreatment. Then it tapped again, harder still.

I propped myself on both elbows and looked toward the farthest tall window, moonlit. In the lower right comer, the size of a bucket, was a long black head with upcurved horns. The Devil, who else? For me, why else? He had heard Stooks blame me and was here to gloat, if not to haul me off to Hell. Like most boys then, I had a general notion of Hell, useful in sorting through life’s million choices and oddly appealing, as a balance for Heaven, to a child’s ruthless hunger for symmetry.

Tap tap again. His horns were knocking the glass to break it. In another minute he’d be in on me, choking or pressing me down to death. Upright in bed then, I set up a howl. The tapping went on and nobody came. I didn’t think that, with the door shut and an empty room between us, nobody could hear me. With every second I grew more desperate; but addled by sleep, I never thought to stand and run toward light and my family. Maybe my anger and shame also stalled me.

Whyever, I stayed there staked to the bed, crying in terror and the worst self-pity I’d yet indulged. I thought hours passed and it helped not at all that eventually the tapping stopped and the head disappeared. It was surely lurking just out of sight, for my next false move. The bitterest word of all I thought in the eye of that storm was abandonment (or whatever form of the word I knew). I never felt a trace of guilt for cheating at cards — what were cards but a game? — and before much longer, I passed the black point at which I expected rescue or even life itself.

Then rescue. The shut door opened quickly, grown bodies poured in; and one of them strode to the midst of the room, found the hanging cord and switched on a light. It was my parents with Stooks beside them. Later I learned that the next-door neighbors had heard my cries and alerted my parents. I’d never been gladder to see anybody; the concern on their faces was almost enough. The thing that muddied the rescue of course was Stooks there, grinning and saying “You’re fine, nothing wrong with you.”

I raced to tell of the Devil’s head and the butting horns.

My father especially heard the news grimly. He believed in the Devil and God more than most.

Mother said something like “Whoever you saw, he’s far-gone now.”

Stooks had to wade in with a quick line of jokes, “The old Scratch loves little tender white meat” (Scratch was the Devil’s local nickname).

When he kept on laughing, I’m sorry to say I told him I knew why Little Frances left. I hesitate to guess my actual words, but right now I know they meant to be Satanic.

I wonder still if Stooks really heard me. My memory is dim on the aftermath, but I think he said “Well — ” or some such lifeless baffled word. I know his face fell in on itself; and though he kept standing there, he said no more.

I can’t believe my mother didn’t hear; but then or later, she never responded. With her adherence to the laws of family love, I know she’d have made me beg Stooks’ pardon. But next she told the men to leave us. Then she went to the pitcher and bowl on the dresser (there was no bathroom). She wet a cloth with cool water and, old as I was, she washed my face and finally asked for details on the Devil.

I pitched in, telling it all again and scaring myself almost as bad as the moment I saw him.

Then the door reopened and Father was back. I’ve said that I saw, right off, he believed me. Far more than anybody else we knew, he saw the powers of Good and Evil as utterly real and always ready at the tips of our fingers, the crack of our lips. He said “Son, that was a cow you saw — Buck Thompson’s cow. I went out there with Ida’s flashlight. There’s a pile of manure and some deep hoofprints. Buck’s out there right now, tying her up.”

I let them think that news relieved me, but I also knew it would cause much laughter in the living room (what Reynolds’ overheated mind had made from a cow). But then and now, half a century later, I have long spells of knowing I saw the pure condensation of evil that night — no comic Scratch but the cause of all hate toward children and beasts, the personal manager of Frances’ torture who reached toward me in the stifling night and helped me strike my uncle Stooks Rodwell a cruel blow.

Stooks lived on another ten years. I know he was back home many more times, but I’ve kept no memory of his face or voice after that bad night. Maybe my mind was too ashamed, of what I’d thought and said in meanness, to store later pictures of his final years (I know he never taunted me again). I also have no recollection of Mother mentioning Frances after that, in the twenty-four years she lived. The obliterating mercy of time is widely praised; but Mother was not the woman to bury thoughts of a loved one — surely no child that died in innocence, gnashing her teeth.

Yet when Mother died and I winnowed the tons of paper she left, I found no trace of the old framed picture of Frances Rodwell with the close-held smile, on death’s doorsill. And so I lived for nineteen years past Mother’s death, four decades past the Devil’s visit. The merciful time, in one of its notable lightning-changes, donned a monster face and struck me with a spinal wound that consumed four surgeries and 4,000 rads of blistering X-ray.

By then Little Frances was gone more than fifty years; every member of our family who had known or seen her was also gone. And I’d thought of her only when passing a friend who limps a little from childhood osteomyelitis, in the 1930s. So it came as a shock to meet her once more but a shock that calmed into one of the actual helps I gave myself, or was given, in my own bad times.

In the first night after my third surgery, which spent nine hours inside a foot-long stretch of my spinal cord with lasers and knives, I was on morphine; but it helped very little. My previous times on strong doses had all been dreamy womblike days of absolute safety and dreamless nights of deep brown rest. Only when the drug was withdrawn after three or four days would I dream again, mostly nightmares as though my mind must suddenly splurge on terror after its long pause. But this third time, the opiate flew on through me helpless as fruit juice to touch my pain. And all that night I woke fairly often and told my tape recorder the dream I just had. Most were stories.

Listening now to the halting tape, I can still be held by two of the dreams, both thoroughly pleasant. The first was a poem about a piece of music that, more than once, had helped me survive.

One of the palpable reproducible pleasures of the race —

To lie in a dark room and hear Bach’s third orchestral suite

Build and destroy, assail and regale its golden pavilions

In the air of one’s ears:

The healing light of utter power,

Utter content, actual promise.

In the second dream my mind took the urinary problems of a bedridden paraplegic and wove them into a full-dress imitation Bible-story. On his deathbed an aged patriarch bade farewell to his grieving sons by explaining the useful symbolism of the shape of a large pee stain on the sheet. The name of the stain, he said, was Djibouti; and somehow to me that seemed good news, worth storing at least.

But then as the pain continued to mount, sometime near dawn I underwent my old boyhood dream of total paralysis. I noticed two big differences at once — I’m now a grown man on a hospital bed, not a boy in a tent; and at first I seem entirely alone. The fear of my body’s total stall is as high as ever though. I don’t give a thought to Little Frances; she left my mind too long ago. Yet when I fail to wake myself, my frozen eyes begin to catch a rising light on the bed to my left. I do my best to watch it, and what I finally manage to glimpse is a woman my age in a standard issue hospital gown — blond hair but streaked with gray. Her eyes are clamped shut; can it be my cousin Marcia?

But then as I watch, her whole body gives a terrible shake as though an awful fist has struck her. Next her fine head jerks back hard; and still not opening her eyes or turning, whatever afflicts her draws her whole shape up from the bed till she makes an awful hoop in the air. I hear the sickening crack of bones as her head and heels meet beneath her. Then she turns one slow revolution above me till her face meets mine. Her eyes split open and of course it’s Frances — grown, even older and worse off than me.

I try to think of

a way to thank her, to beg her pardon for using her name to punish Stooks — his face sweeps past me for the first time in years, falling in on itself as it did when I hurt him. No way I can reach out and bring him back. I only think that maybe here, in my own ordeal — if I bear it more bravely — I can somehow reach back and lighten Frances’ own long crucifixion. Someway I can suffer, here and now, to lighten her pain all those years past.

But when I find that my lips can open, my tongue can move, Frances starts to fade above me. Not before she speaks two words. Just as she’s almost gone from the room, her parched lips move; and she says “Stay here.” I understand she’s heard my offer, silent as it was, to suffer for her. So I stay as she goes; and then I try to draw my mind back down inside me and wait in dignified calm, if not peace.

In general I’m readier than most of my friends to share the ancient human belief that some dreams may well come from outside us, as warnings or omens or practical aids from whatever made us and watches our lives. So even now I’m not prepared to swear that Frances didn’t really arrive in my mind that night, on a useful mission. Likewise I stay open-minded on what her two words meant. “Stay here” — stay where? In a hospital bed in driving pain? Or stay on Earth till she comes back and leads me again? But where to and how? Is part of the trouble I’ve recently known intended to do what I guessed in that dream — to give some backward help to Frances; some sharing and thinning of her ordeal, her dreadful knowledge?

Whatever it meant and goes on meaning, I obeyed her. I stayed, that night and till now. When I woke at daylight after she’d gone, the upper half of my body could move. My legs were still frozen, useless as logs screwed onto my hips. But three years later my hands still work and have told this story. When Marcia and I and all our generation are gone, at least this picture of one good child’s burning death will stay behind us.

No one could help Frances Rodwell back then, even there at her bedside with cool compresses. How much less can I reach her now, a boy cousin not even born when she died. But strangely now I can hope to save her simple name a few years longer by fixing her fierce ordeal in words that may or may not move a few readers to look her way in their own short spans — a golden child raked down by the dark but ready to live again any year, in a patient mind that pauses a moment and gives her room.

Tags

Reynolds Price

Reynolds Price was born in Macon, North Carolina and lives in Durham. His twenty-first book — The Foreseeable Future, three long stories — will appear this spring. (1991)