This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 1, "The Golden Child." Find more from that issue here.

Green Forest, Ark. — Steve Work first noticed that his family’s well water tasted slimy back in 1983. “Everybody got sick,” recalls Work, a glassblower in the Ozark Mountains of northwest Arkansas. “When we’d make coffee, we’d get an oily scum on top. We finally figured out it was chicken fat.”

Catfish died in farm ponds, and Dry Creek was choked with dark, greasy sludge. When state inspectors tested drinking water in the area, they soon discovered the cause of the trouble: Raw sewage had polluted groundwater across 60 square miles. The governor declared it a disaster area, and ordered the National Guard to haul safe drinking water to thousands of families.

There was little doubt about who was fouling the water supply. Tyson Food, the largest poultry company in the nation, operates a huge “processing plant” in Green Forest. The slaughterhouse dumps so much blood and chicken fat and chemicals into the water every day, the town had to build a bigger sewage plant to handle it all. The expanded treatment facility, completed in 1988, is big enough to provide clean water for a city of 75,000. Green Forest has a population of 2,050.

Steve Work and his neighbors complained to Tyson about the sewage, but the company responded by threatening to close the plant and lay off workers. Angered, 110 residents sued — and won a partial victory. In May 1989, a jury ruled in their favor, but U.S. Judge Oren Harris levied a fine of only $254,680 — just enough to cover their property damage and pay for new wells.

The citizens say they are pleased with the jury verdict, but stress that it will take much more to force Tyson and other poultry companies to clean up their act. “The industry does research on reusing waste,” Work says. “But they’ll only do what’s profitable. If there’s not profit in stopping pollution, they won’t stop unless someone makes them.”

The Farm

What happened in Green Forest is scarcely an isolated incident. Once a scattered backyard business, raising chickens and turkeys has become a massive agricultural industry concentrated in half a dozen Southern states (see “Ruling the Roost,” SE Vol. XVII, No. 2). Thousands of poultry farms and processing factories churn out millions of birds every day — along with carcasses and chemicals that contaminate the land and poison the water with toxic wastes.

The numbers are staggering. Industry studies indicate that every bird sold leaves behind 2.5 pounds of manure and 5 gallons of waste water. With the industry turning out 5.7 billion chicken broilers annually, that comes to nearly 14 billion pounds of manure and 28 billion gallons of waste water each year.

“It’s a serious threat,” says Sam Ledbetter, the attorney who represented the Arkansas citizens who sued Tyson. “Poultry waste is usually 11 or 12 times stronger than raw domestic sewage. It can devastate rivers and streams. Ultimately, we’re talking about jeopardizing groundwater throughout entire areas.”

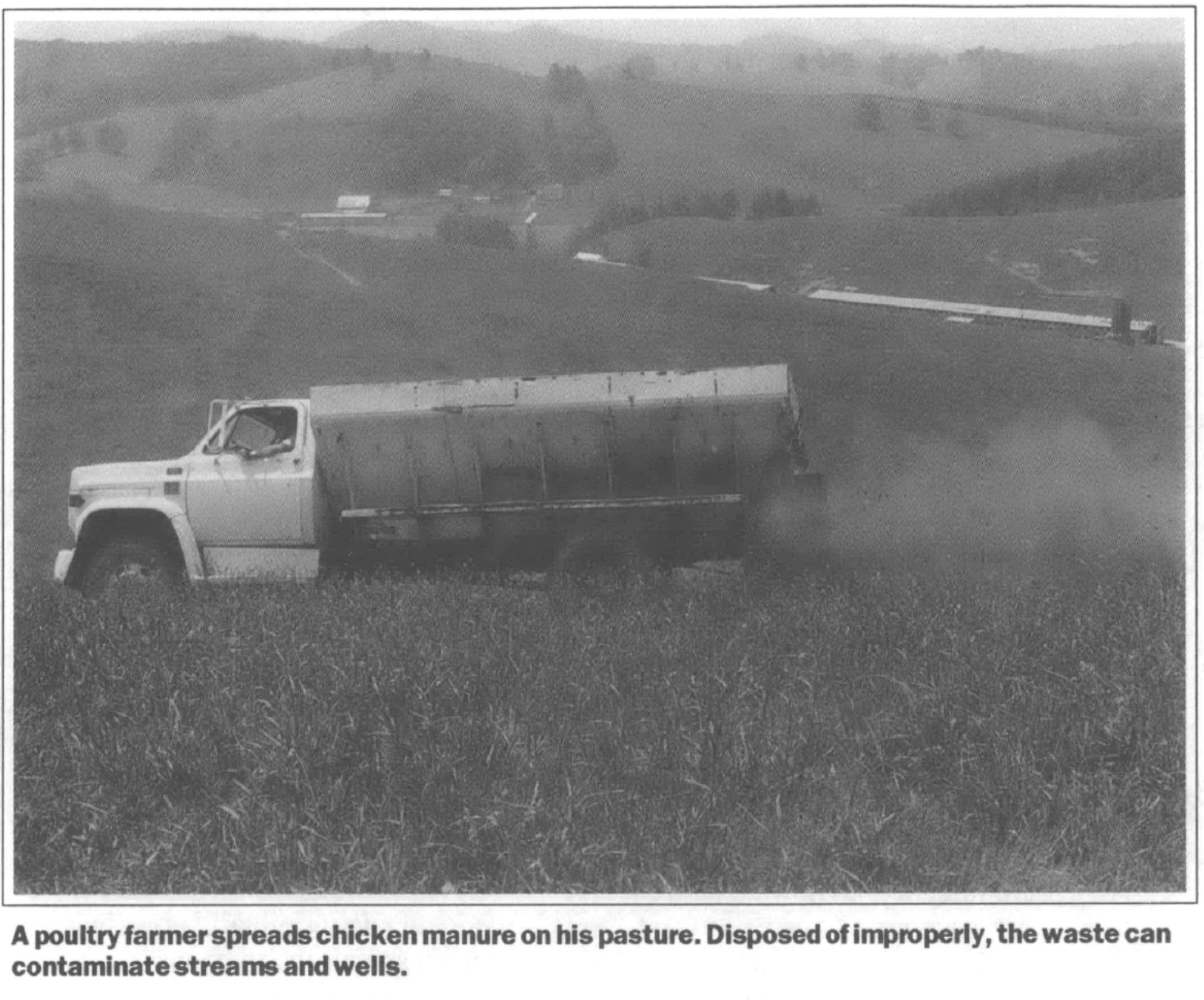

The pollution starts on the farm, where thousands of birds are packed into chicken houses. During their brief stay, the birds drop tons of manure that mix with feathers and wood shavings — a smelly mess the poultry industry likes to refer to as “litter.” After six weeks, the poultry company retrieves the birds, leaving the farmer to dispose of the litter.

Poultry manure contains high levels of nitrogen and other nutrients that can fuel the growth of aquatic plants and use up oxygen, choking streams and killing fish. The manure can also contain metals, bacteria and other pathogens, cancer-causing pesticides such as heptachlor, and residues of arsenic used to control parasites in the chickens.

Farmers have traditionally spread the manure on fields as fertilizer, but the sheer volume of waste is using up the available land. Studies indicate that farmers need nearly four acres of land to safely dispose of a ton of poultry manure — and Arkansas alone produces 2.11 million tons of litter each year. Disposed of properly, the waste would cover more than eight million acres — almost a quarter of the entire state.

“More and more agricultural facilities are being opened up,” says Don Morgan, an inspector with the Arkansas Department of Pollution Control. “There’s just more litter generated than there is land to handle it.”

And not just any land will do. The waste must be spread on flat ground to prevent runoff, kept away from streams and wells to prevent contamination, and surrounded by trees or shrubs to prevent leaching. In addition, litter should not be applied during a rain, and should be cut into the soil with a disk.

“We at this very minute are cleaning out our houses and spreading the litter on our fields,” says Benny Bunting, a poultry grower in Martin County, North Carolina. “We’ve got about 40 loads from three chicken houses — about 450 tons of litter in all.”

The problem, Bunting says, is that more and more growers don’t farm, which means they have nowhere to put their manure. “If you don’t have farmland, the litter usually stays stacked in piles all year. That means you’re going to have rain on it, and you’re going to have nitrates running off straight into ditches.”

In truth, nobody knows how much chicken waste is improperly spread or dumped by farmers. Most Southern states grant agriculture a variety of exemptions from environmental regulations, and virtually none regulates or even monitors on-farm practices.

To make matters worse, farmers also have to find a way to dispose of dead birds. Poultry operations raising 20,000 birds lose an estimated 1,000 a flock, most when they’re under a week old. Based on current production, that’s nearly 285 million carcasses each year.

With limited land available to dispose of manure and bones, industry officials are touting composting as the solution. Composters transform litter into clean fertilizer, and model systems have been built on farms in Alabama, Arkansas and Virginia. But building and operating composting units costs more than $100,000 — an unmanageable financial burden to poultry growers already deeply in debt.

Mary Clouse, a former grower and editor of the Poultry Grower News, says farmers themselves are the hardest hit by poultry pollution. “The growers are the first to suffer,” she says. “They don’t want to pollute their environment. But if there’s no money, forget it!”

The Factory

The pollution intensifies when poultry companies truck the birds from farms to factories to be slaughtered, gutted, and packaged. The chickens arrive caked with dirt and feces, and flow along an assembly line that repeatedly soaks, sprays, and rinses them with water. They are dipped in tanks of scalding water and defeathered by machines that fill the air with a fine mist. After they are gutted, they are chilled in large water tanks. “At the beginning of the day the chill-tank water is clear and clean,” one inspector told The Atlantic Monthly. “But as the day goes on, it becomes murky, dirty-brownish, and bloody.”

By the end of each day, millions of gallons of water have been transformed into a “fecal soup” of chicken droppings, blood, and grease teeming with bacteria, parasites, and viruses. The companies also release tons of ammonia, phosphoric acid, and other toxic chemicals directly into the environment. But according to a recent industry survey, many companies have failed to report chemical discharges as required by federal law, and have failed to train their employees to fill out government reporting forms.

“Who knows what all goes on in these plants?” says Tom Aley, a hydrogeologist who directs the Ozark Underground Laboratories. “We know they spread things like salmonella and other bacteria in the groundwater. There may be more dangerous things with long chemical names, but in reality the most imminent health threat is just regular old sewage, like the waste from poultry plants. It may not sound glamorous, but it’s a significant danger.”

Some poultry plants have their own pre-treatment facilities to clean up contaminated water, but the process produces waste problems of its own. Sludge that settles in specially constructed lagoons must be monitored for leaks and spread on nearby fields.

When Tyson Foods built a storage lagoon near the town of Clifty, Arkansas, local residents were dismayed. There had been no public hearing, no warning the lagoon would be built. Soon the company began applying the sludge to fields and selling it to local farmers for fertilizer.

“The odor was terrible,” recalls Jo Cox, who lives half a mile from the lagoon. “The sludge was put on so thick the buzzards flocked, and flies were a problem, too.”

But the worst shock came when residents tested their well water and discovered dangerously high levels of streptococcus and coliform bacteria. Residents complained to state environmental officials, but Cox says they received “very little cooperation.” Tyson had received a state permit for its waste lagoon — located on a flood plain — but regulators were making no effort to ensure it was properly maintained.

Tyson was also unwilling to listen to residents — until they decided to sue. “Then Tyson decided they wanted to talk,” Cox says. The company agreed to clean out the lagoon, fill it with earth, and stop spreading sludge. In return, the citizens dropped their suit.

“Interim” Pollution

Although most states require poultry companies to obtain permits before they dump waste, enforcement of environmental safeguards is generally lax. Even when companies are repeatedly cited for violating water quality standards, state officials often grant them “interim permits” that allow them to continue polluting for months or even years while they “work to correct the problem.”

When Perdue Farms built a plant to treat waste at its slaughterhouse in Accomac, Virginia in 1973, it waited

until construction was complete to apply for permission to dump waste into nearby Parker Creek. Given the go-ahead by the state, Perdue began discharging chicken grease and bacteria into the water.

Once a pristine habitat for fish and crabs, Parker Creek grew gray and slimy, clogged with algae and other plant life. Except for the overabundant plants, aquatic life disappeared.

Despite the destruction, Perdue complained that the limits on pollution were too strict. State officials responded by relaxing the regulations, issuing an “interim permit” that allowed Perdue to continue dirtying the creek.

But even the interim standards proved too tough for Perdue. In May 1989, storage lagoons overflowed and discharged massive clumps of sludge into the creek. Finally, when the company discharged illegal levels of ammonia into the water in January 1990, the state fined the company $75,000.

Because many poultry plants are located in rural areas like Accomac, they often dump their waste directly into nearby lakes and streams. In northeast Georgia, a special grand jury has been working since 1986 to investigate poultry companies that discharge wastewater into creeks that empty into Lake Lanier, a popular swimming resort and a major source of drinking water.

In 1989, college students testing the water at Lake Lanier discovered extremely high counts of fecal coliform bacteria at three of the lake’s most popular beaches. The Army Corps of Engineers was so alarmed it asked that the beaches be closed, but the state Environmental Protection Division refused to act.

Fieldale Farms, a poultry company that processes 2.5 million chickens a week at three slaughterhouses in the area, dumps waste directly into creeks that flow into Lake Lanier. Last October, a local resident noticed a foul discharge running from Fieldale’s Murrayville plant through a ditch to Gin Creek, and used a citizen hotline to notify state officials.

When state inspectors visited the plant, they discovered wastewater pouring from a pipe into a ditch that leads to Lake Lanier. Former Fieldale employees said the illegal discharges were standard procedure. “We knew what we were doing was wrong,” said Brian Gaut. “But we had to get rid of the waste.”

The state slapped Fieldale with its fourth citation for water-quality violations in four months, and fined the company $135,000. It was the first time in Georgia history that a company received the maximum penalty for a water-quality violation.

For now, Fieldale is being allowed to continue operating while it applies for a new permit. “We could revoke all permits and not allow production,” says Larry Hedges, manager of the state industrial wastewater program. “But the offshoot would be a severe economic fallout, because the community would lose jobs.”

“Awful Lenient”

Blessed with such cooperation from state officials, poultry companies often take a high-handed attitude when asked to clean up their pollution. One of the most blatant and unrepentant polluters in the region is the House of Raeford, which operates chicken and turkey slaughterhouses in eastern North Carolina.

According to a 1987 memorandum in the files of the state Division of Environmental Management, the history of pollution violations by the House of Raeford “indicates a total disregard for compliance with environmental law.” The memo recommended criminal charges be brought against the company’s officers.

The state repeatedly cited the House of Raeford turkey plant in Rose Hill for polluting nearby streams. But instead of adopting the memo’s get-tough approach, regulators allowed the company to continue dumping waste under an interim permit.

Frustrated by the lack of action, the city of Raeford decided to take on the company itself. After citing the poultry firm with 100 violations last spring, the city threatened to stop treating company waste at the municipal sewer system.

“We’ve been awful lenient with them for years, giving them plenty of chances to comply,” said City Manager Tom Phillips.

But the company fought back, and Superior Court Judge Craig Ellis ordered the city to continue providing water and sewage service to the company. “I’m right, and right is supposed to win,” crowed House of Raeford President Marvin Johnson after the ruling. “I’m not cocky or anything. I just want to show my side. If they want me to leave, I’ll shut it down.”

When local officials filed criminal charges against the company, the courts again sided with the House of Raeford. A judge dismissed the charges, saying the company could not be accused of violating a permit it didn’t even have. He fined the firm $15,000 for misdemeanor pollution charges — and suspended the fine for five years.

Outside the courtroom, Johnson and company attorney Henry Jones were jubilant. “Until state lawmakers make it unlawful to violate a permit when you don’t have one, that’s the way it is,” Jones told a local reporter.

“Come by the office,” Johnson laughed. “I’ll give you a turkey.”

Don’t Drink the Water

Like the town of Raeford, some communities are starting to insist that poultry companies and farmers clean up their mess. Rockingham County, Virginia, one of the biggest poultry centers in the nation, now requires all new growers to submit a plan to dispose of all waste produced. Existing growers don’t have to submit a plan until 1994.

But for the most part, regulation of poultry waste remains lax. Few growers in the South are required to come up with waste management plans. Arkansas, where poultry firms make 44 cents of every agricultural dollar, doesn’t have any safeguards regulating dry waste from chicken farms and factories. In North Carolina, only two percent of all animal-growing facilities are inspected each year.

Some states are even considering eliminating the few environmental safeguards they do have. In North Carolina, the state agriculture department recently backed a bill that would exempt poultry manure and other byproducts of food processing from state regulations. The result: Like growers, processors would not have to get a permit before they dumped waste on fields and streams.

“They will be free to disperse the greasy junk on open land as fertilizer, process it as animal-feed supplement, or put it to ‘other beneficial agricultural uses,’” the Raleigh News and Observer editorialized. “The state agriculture department is once again on the wrong side, blandly hewing to its standard line that whatever agribusiness wants, agribusiness should get . . . leaving Bre’r Fox in sole charge of the hen house.”

As pollution from the poultry industry increases, citizens who have grappled with poultry companies say there is a better way. Companies must be required to take responsibility for all the waste they produce, from the farm to the factory. States must insist that firms build composters, recycle manure, conserve water at slaughterhouses, and properly dispose of processed sludge — and officials must back up those regulations with regular inspections and strict enforcement.

Steve Work, the Arkansas glassblower, still remembers how sick he got every time he drank water from his well. “They say you can’t drink the water in Mexico,” he laughs. “Hell, I went there on a business trip once, and I felt better! The water quality there is better than it is here.”

“Poultry companies are trying to shift the responsibility off onto the government,” Work concludes. “They say, ‘We pay our sewer bill, it’s up to you to take care of whatever comes downstream.’ Now, I’m not anti-industry by a long shot; we need business and jobs. But I do think it’s time these polluters start acting like responsible citizens — before more damage is done.”

Tags

Denise Giardina

Denise Giardina, the author of Storming Heaven, lives in Whitesburg, Kentucky. (1991)

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.