Of Different Minds

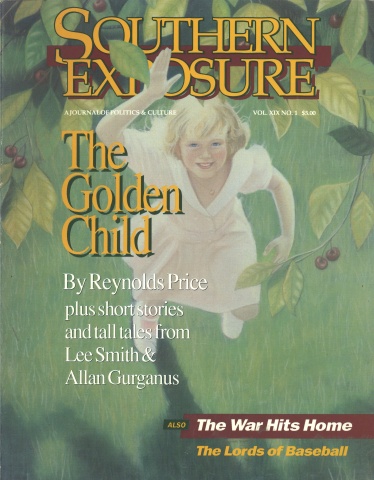

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 1, "The Golden Child." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Winston-Salem, N.C. — Dr. David Hackett Fischer stood at the microphone before 500 people looking very uncomfortable. A professor at Brandeis University, he was trying his best to defend the author of a book on Southern history.

“When we judge him by the standards of his own time, he was a liberal,” said Fischer. “He spoke out against the Ku Klux Klan, against lynching, when it was not merely unpopular, but dangerous to do so. That liberalism may pale when we measure it against our standards, but I think it was very real nonetheless.”

Dr. Nell Irvin Painter was quick to respond. “I’m sorry, I have to disagree profoundly. There were people in his world, black and white, who stood for the things that he mouthed. He only looks good because there were so many people saying so many awful things in his world. But he lived in the same world as Lillian Smith and Jesse Daniel Ames, a world in which other people were actually doing things. You don’t have to be a black reader or a woman to see the patronizing language that he uses.”

At first glance, the exchange seems unremarkable. After all, what could be more commonplace than a white man and a black woman disagreeing about Southern history? Such is the stuff history conferences, if not the South itself, are made of.

What was unusual about the exchange was the subject. Fischer and Painter were speaking to hundreds of people at Wake Forest University, including some of the leading Southern scholars and journalists of the day, all of whom were devoting an entire weekend to discussing a single book. Not Gone with the Wind, not The Sound and the Fury, not anything by Faulkner, for that matter. These academics and writers had come from all over the country to mark the 50th anniversary of the publication of The Mind of the South by Wilbur Joseph Cash.

When W. J. Cash finished his first and only book in 1941, he could scarcely imagine the enduring impact it would have. Fifty years later, it remains a source of controversy and contention among those who study the South.

Cash himself never lived to see the debate he sparked; drunk and despondent, he hung himself in a hotel room in Mexico City shortly after the book appeared. But his work survived, and over the years it has taken on a curious life of its own. The book has never gone out of print, and continues to sell as steadily as many Faulkner novels.

“I would venture to guess that no other book on Southern history rivals Cash’s in influence among laymen, and few among professional historians,” said Dr. C. Vann Woodward, professor emeritus at Yale. “It changed my life,” agreed Dr. John Hope Franklin, professor emeritus at Duke. “I never write a word without thinking of The Mind of the South.

One South?

Why have some of the most prolific historians lavished such praise on a book written by a reclusive, brooding, little-known journalist of the 1930s? Because Cash artfully shifted the focus of Southern history, examining how the region was shaped by the forces of race and class.

Drawing on Marx and Freud, Cash probed the ego of the white Southerner from frontier days, through the rise of the plantation and the bloodbath of the Civil War, to the rule of cotton and lynch law. Why, Cash wanted to know, did common whites ignore their own social and political interests and follow the master class of planters and their descendants? Or, as Dr. Richard King put it at the conference, “Why had the South of Thomas Jefferson become the South of Nathan Bedford Forrest?”

To Cash, the South was a society built on class, but lacking any class consciousness. Simply put, poor whites followed the wealthy because they identified with the culture of white supremacy. Southern society crushed them into the ground day after day, yet they cherished it, yielded to it, marched off to die for it. The underlying reason: the triumph of racism.

Rich planters created loyalty among “white trash,” Cash argued, by directing their fears and hatred against blacks. “Add up his blindness to his real interests, his lack of class feeling and of social and economic focus, and you arrive, with the precision of a formula in mathematics, at the solid South.”

But Cash was not looking for some simplistic formula. On the contrary, he reveled in contradictions and searched for multiple causes and motivations behind every development. Cash wanted to capture the mentality of the South, its “folk mind,” its values and ideas, feelings and moods — in short, its very consciousness.

It was a remarkable undertaking, and the rich prose and imagination Cash brought to the task remain magnificent half a century later. Yet Cash also had a love of generalizations, and his emphasis on the essential unity of the Old South — and its unbroken continuation into the modem world — flawed his theme in two fundamental ways.

First, as C. Vann Woodward and others at the conference pointed out, Cash was so bent on proving that the New South remained virtually the same as the Old, that he overlooked the dramatic changes and conflicts that shaped the region.

“He denied that there was any significant break between the Old South and the New South,” Woodward said. “Any changes brought about by secession, civil war, defeat, abolition of slavery, reconstruction, redemption, or industrialization were to his mind ‘essentially superficial.’”

Thus, Cash overlooked diversity and underestimated dissent. He ignored the masses of white Southerners who opposed the Civil War, paid little attention to the Populist movement that rocked the region, and never mentioned his contemporaries who were struggling to right the wrongs he so eloquently condemned. “If it can be said there are many Souths,” Cash wrote, “the fact remains that there is also one South.”

And therein lies the second flaw in The Mind of the South. To Cash, the “one South” was the South of the white man. “W. J. Cash was fettered by the very conventions he sought to describe,” said Dr. C. Eric Lincoln, professor of religion and culture at Duke University. “He labored under the illusion that the ruling mind is the only mind.”

By excluding blacks and women from “the South,” Cash ultimately prevented himself from ever fully understanding the region in all its richness and diversity. Worse, he sometimes descended into outright racism, as when he described the Negro as “notoriously one of the world’s greatest hedonists . . . a creature of grandiloquent imagination, of facile emotion, and, above everything else under heaven, of enjoyment.”

Cash, in the final analysis, was no hero. He did not join in the struggles being waged to change the region for the better. He sat at his typewriter, brooding, writing, depressed at all he saw, while all around him the ordinary Southerners he ridiculed and the blacks and women he ignored were risking their lives to make the region a better place to live.

But to accept that Cash was no activist misses his place in the history of Southern thought. As a work of the imagination, The Mind of the South remains an essential component to any understanding of the class dynamics of the region — of the ways in which ruling whites continue to wield race as a whip to keep other whites in line.

“It is far easier, I know, to criticize the failure of the South to face and solve its problems than it is to solve them,” Cash wrote in the final paragraphs of his book. “Solution is difficult and, for all I know, may be impossible in some cases. But it is clear at least that there is no chance of solving them until there is a leadership which is willing to face them fully and in all their implications, to arouse the people to them, and to try to evolve a comprehensive and adequate means for coping with them. It is the absence of that leadership, and ultimately the failure of any mood of realism, the preference for easy complacency, that I have sought to emphasize.”

“Six Feet of Dirt”

Dr. Bruce Clayton, professor of history at Allegheny College, is the author of a new biography of Cash published by LSU Press. He spoke about the world Cash knew as a boy:

No one, I am sure, would be more surprised than W.J. Cash to learn that anyone, let alone academics, would be gathering to say happy birthday to The Mind of the South. Think of all those nasty things he said about the region — its narrowness, sentimentality, stubborn blindness to its faults, its violence and inherent racism.

Thus Cash, born and bred in the South and one of its loyal sons, rejected — rudely, but oh so artistically — the very world of his mother and father and those who were bone of his bone and flesh of his flesh.

Bom in 1900 in Gaffney, South Carolina, in the heart of the Piedmont mill country, Cash knew the folk culture of the South intimately. His parents were good country people, sturdy, unassuming, uncomplaining and hard-working. Cash’s father clerked in a local mill and watched, admiringly, as his ambitious older brother climbed the business ladder.

The Cash brothers, one or two rungs above the mill hands, did not hold with unions, abhorred strikes, and embraced the owners’ oft-trumpeted assertion that they had built the mills to bring jobs to the needy whites — a view seconded with numbing frequency by the town fathers.

In religion, the Cashes were staunch Baptists, as were the majority of their neighbors — “fundamentalists,” in today’s parlance. “Foot-washin’ Baptists,” Cash called them. Mama and Daddy Cash looked with alarm at Gaffney’s deserved reputation as a hard-drinking, violent town. But no more than their neighbors did they question white supremacy. Gaffney was in the center of a virulently racist culture where segregation was the unquestioned rule and racial violence, often brutal, abounded.

Gaffney’s whites extolled the virtues of the “old-time” Negro and issued dire warnings against the black rapist. In this they were egged on by the state’s race-baiting political leaders, Benjamin Tillman and Coleman Blease. On one occasion in Gaffney, “Coley” Blease shouted to an admiring throng that “when a nigger laid his hand upon a white woman, the quicker he was placed under six feet of dirt, the better.”

In such an atmosphere, terms like decency and humanity could be stretched to the limit without embarrassment. In 1906, the year Cash was six years old, a massive mob in a nearby county took an accused Negro rapist from jail, tied him to a tree, and riddled his body with bullets. Only the pleas of a well-known moderate, said the local newspaper approvingly, prevented the crowd from burning the man alive and prompted a “humane man” to “pull the doomed negro’s hat over his face before the crowd started shooting.” Then the victim’s head “was literally shot into pulp, his brains covering his hat and face.” Such was Cash’s boyhood world.

“A Special Alien Group”

Dr. Nell Irvin Painter, professor of history at Princeton University, spoke about what Cash left out:

The publication of The Mind of the South and this symposium are separated by an historical watershed that invalidated much of what Cash assumed about the South: the civil rights movement. The movement engendered fundamental changes in Southern life, which extended to its universities and created the possibility of my being here today.

As an embodiment of the changes that undermined so much of what Cash had to say, it strikes me that my commenting on his book represents a clash of generations that allows no graceful exit. Cash wrote of “the mind” of the South without envisioning that women and black people might have a capacity to reason independently.

Like so much writing from the American intellectual tradition before the civil rights and black studies movements, The Mind of the South was not intended for eyes like mine. Writing to fellow white North Carolinians, educated white Southerners, and Northern book buyers, Cash never conceived of any but the most informal black or female critics.

Although I respect the book’s persuasiveness for masses of readers and have assigned it in my Southern history courses, I have never been susceptible to its magnetism, as have so many of my white male colleagues.

When I first encountered The Mind of the South as an undergraduate in the early 1960s I thought it thoroughly racist. My graduate student rereading of it in the early 1970s revealed it as deeply sexist. Rereading it as a teacher in the 1980s, I was struck by Cash’s contempt for the poor of both races and his blindness to the ways in which slavery and racism had distorted the Southern polity. I was shocked that he could speak of an “old basic feeling of democracy” in the slave South, which I think of as a society in which one-third of the men did not even own themselves, never mind vote.

For Cash, “the Negro” is not part of “the South.” He goes so far as to identify “the Negro” as “a special alien group” whose presence assures the fact of an enduring white unity.

Nonetheless, Cash mentions the presence of Negroes as an apparent but not decisive factor distinguishing the South from the North. He also admits that “the Negro” has influenced the way the white man thinks, feels, speaks, and moves. Alien though he may be, Cash’s “the Negro” functions as a potent force in the mind of the South.

At the same time, however, Cash is entirely uninterested in the Negro as an independent historical actor. It was as though Cash had created a potent force, then denied it agency. “The Negro” represents a virtually powerless figure. Cash could not imagine black men as political actors who would be a positive force in the South.

“Wages of Accommodation”

Dr. C. Eric Lincoln is the author of The Black Church in the African-American Experience. He related his own childhood experiences to The Mind of the South:

Cash’s “mind of the South” is strictly a white mind. Black Southerners are entirely excluded from his concept of this mind; for that reason, his inquiry is limited from the start.

The South was and is about Negroes, blacks, African Americans. They figure with implacable pervasiveness in every area by which the region is defined: economics, law, politics, religion, sex, social relations — the list is endless.

Take away the black component and the whole notion of “the South” collapses. It becomes unimaginable, like Lawrence in Arabia with no Arabs.

I know what Cash was writing about. I know about “black men singing . . . sad songs in the cotton.” I know because I was there in the cotton, and I was black. And if I never sang sad songs on such occasions, I heard those who did and cursed them for their resignation.

And if I didn’t know that the “po’ crackers” and the “white trash” were descended from “convict servants, redemptioners and debtors,” as Cash claims, I did know instinctively to stay away from them. Whatever their origins, po’ white trash meant trouble — lots of trouble. And to many a black man, that trouble proved terminal.

My grandmother was constant and insistent: “Son, when you have to go into town, go on directly about your business. Don’t have nothing to do with that white trash hanging around the courthouse yard. Don’t fight with them redneck boys, and don’t even look at them po’ white gals. Just do your business and get on back home directly.” A reasonably effective prescription for survival.

Yes, I knew the po’ white trash had an unabated lust for my blood, but at the time, I didn’t understand why. Nor did I know for sure that behind the so-called rednecks who so readily laid down their Bibles, quit their revivals, and leaped from their pulpits to go “coon hunting” was all the time the stealthy hand of the “quality white folks,” who taught us to hate the “trash” in the first place.

I worked for “quality folk” for 50 cents a week and my breakfast, leaving home at three in the morning to be a milk boy for a small dairy. I washed the steel crates of thick, heavy glass bottles and delivered the milk and cream to the front porches of the sleeping gentry until eight in the morning. Every morning.

My Grandpa milked 18 cows twice a day, every day. And for that the “best people” paid him $3.50 a week, and praised him for his industry. My Grandma washed and ironed for the same family of five white folks of the very best quality, who paid her $1.25 and called her “Aunt Mattie” with that peculiar affection and respect quality white folks reserve for their favorite black retainers.

That $5.25 we managed to eke out together meant survival. It was the wages of accommodation to a system that taught us to work without stinting, hate the cracker, be suspicious of the Jew, and maintain a developed sense of contingency to a recognized family of the ruling class. This was the understanding that put bread and salt and pork on the tables of the “good” — the accommodated — Negroes; insured them against “trouble with the law”; kept the po’ white trash at bay; sent the white doctor to see them when they were down sick; and brought the white folks they worked for to their funerals when they could work no more.

At the very time that Cash was being hailed for his disclosure of the traditional establishment “mind of the South,” a countermind which was destined to change the South forever was taking on definition in the form of a civil rights revolution. The truth is, there had always been that other mind — denied expression, but there nonetheless. There is such a mind within every repressive society, waiting to be heard. Such is the lesson implicit in the disintegration of the Soviet Empire and the dismantling of South Africa, where the ruling minds ran to Communism and apartheid while the counterminds were bent on freedom.

America has changed a lot in the half century since The Mind of the South appeared. The industries that brought Progress to the South are now taking that Progress to Japan and Korea. The cotton mills which damned the unions, exploited the poor whites, and disdained the Negroes are gone to Hong Kong and Taiwan.

The Ku Klux Klan, that alleged “authentic folk movement,” is authentic no longer. It remains nonetheless a public shrine for the rallying of a diverse collection of unrepentant ankle biters unwilling to accept any part of the painfully wrought, still emerging new world.

This new world is symbolized by those same muted black voices who yesterday sang sad songs in the cotton but today, increasingly, share with their erstwhile “keepers” the delicate decisions determining the welfare of all.

This is true Progress. This is as it should be.

“A Habit of Servitude”

Howell Raines is Washington editor of The New York Times and the author of My Soul is Rested. He spoke about how The Mind of the South can help us understand the South today:

Cash reminds us that social and class conflict in the South are not simple matters. In the 27 years I’ve been a reporter, one of the enduring paradoxes of New South politics has been the tendency of Southerners to vote against their own financial and social interests.

Taking my native Alabama as an example, we see a state that has been operated as an economic colony of the Northeast since 1900, when ownership of the coal and iron deposits around Birmingham passed into the hands of out-of-state investors. The 1901 constitution of Alabama, which remains a millstone around the state’s neck to this day, mandated that these corporations should pay the same property taxes as individuals.

This meant that for decades, United States Steel, in one of the great examples of corporate social irresponsibility in American history, was able to ship Alabama steel and dollars to Pittsburgh, while poisoning the state’s streams, fouling its air, corrupting its politicians, and paying only a pittance in property tax.

Today, Northern paper companies have replaced U.S. Steel as Alabama’s principal absentee landlords. But the legacy of U.S. Steel lives on in the form of the region’s lowest property taxes. Paper-making corporations that pay $4 per acre in property taxes in Georgia and $2 to $3 in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Florida, pay 50 cents to 95 cents per acre in yearly taxes in Alabama.

As a consequence, Alabama has Third World infant mortality rates literally within the shadow of its shiny University of Alabama Medical School in Birmingham. It has a school system so starved for money that even the traditional doormat states of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas are passing it in education funding and educational quality.

Yet last fall — and here we’re coming to the paradox that I think Cash can help us penetrate — Alabama re-elected a governor who has pledged to preserve the tax breaks of the paper companies that are now using the state as one vast tree farm.

Part of the explanation of this tradition of exploitation lies, of course, in the race issue. For 25 years, George Wallace was a loyal protector of the financial interests of the extractive industries in Alabama. He used the race issue to divert the attention of the white voters from the issue of tax equity. Alabama’s corporate masters, in turn, funded his national political campaigns.

But if we are to believe Cash, we must also look to the Civil War to explain the attitude of servitude among many Southern voters, particularly white voters, toward candidates and corporate leaders who perpetrate the exploitation of the region.

In a state like Alabama, only about five percent of the white residents at the time of the Civil War owned slaves. Why were the remaining 95 percent of whites willing to die for the economic interests of the master class?

Cash writes: “Out of that ordeal by fire, the Civil War, the masses had brought not only a great body of memories in common with the master class, but a deep affection for those captains, a profound trust in them. . . . there had begun to grow up in him some palpable feeling, vague still but distinctly going beyond anything he had exhibited previously, of the right of his captains, of the masterclass, to ordain and command.”

Dr. Martin Luther King, the greatest leader to breathe the air of the South in my lifetime, told black people across the region that before they could seek to secure their social freedom, they had to evict the attitudes of slavery from their own hearts and minds.

Cash’s writing on this point suggests that there is still in all Southerners, black and white, a habit of political servitude, a habit of obedience that is deeply rooted in our psyche, and is influencing the political choices of voters up to this day. If he is right, particularly in states such as my home state, the task of the political liberation of the New South has hardly begun.

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.