This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 1, "The Golden Child." Find more from that issue here.

“Uncertainties in the Middle East pose no immediate threat to the supply of petroleum products for American consumers, nor do they necessitate increases in prices for American consumers.”

— Admiral James, Watkins Department of Energy, August 1990

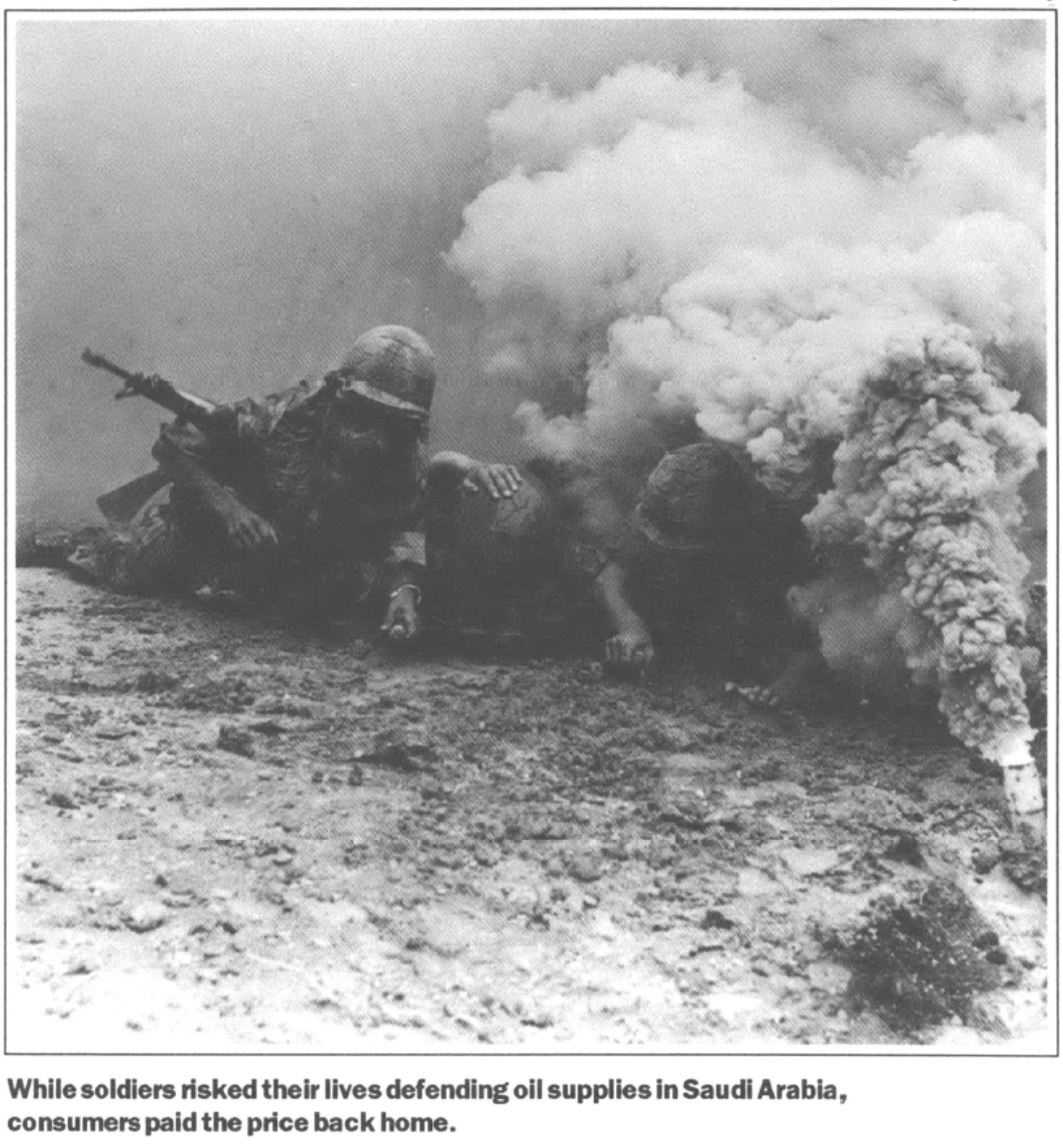

Just days after Iraqi troops set foot in Kuwait, the oil industry launched an energy war of its own on American soil. As Saddam Hussein claimed control of the hotly disputed Ramailah oil fields, George Bush ordered an embargo of Iraqi and Kuwaiti oil. The president also issued a somewhat less belligerent plea to American oil companies to “do their fair share and . . . show restraint.”

But no sooner had Bush uttered his appeal than the price of a barrel of oil jumped from $20 to $28, practically overnight. Service station workers across the country pulled out ladders to increase their advertised prices for a gallon of gasoline — by an average of 11 cents nationwide, according to a survey by the American Automobile Association.

By the time President Bush ordered the bombing of Baghdad five months later, American drivers had paid an extra $22 billion just to keep their vehicles on the road. That means every car-owning household in the country lost an average of $220 at the pump between August and January. Since the rural South depends on cars more than any other region, the price hikes cost Southern households an estimated $175 million more than the rest of the country.

Gregory Keller was one of those hit hard by soaring gasoline prices. Since August, the 38-year-old carpenter has had to pay an extra $30 a week to fuel his Ford pickup as he drives hundreds of miles from his home in Swannanoa, North Carolina to Charleston, South Carolina in search of work. He has had to skip meals to make ends meet — and he has even sold his blood for gas money.

“If I’m not totally stressed and my blood pressure is down, I can donate plasma,” says Keller, who suffers from high blood pressure. “That’s good for $8 — a quarter of a tank of gas. I’ve had to do that.”

Oil companies don’t like to hear that the Persian Gulf shootout boils down to trading blood for oil, either at home or abroad. To them, price increases, if not the war itself, are the product of indiscriminate market forces. “Crude oil and petroleum are commodities and their wholesale prices are determined in commodity markets, just as the price of grain,” says Glenn Tilton, president of refining and marketing for Texaco.

But a review of industry reports, government studies, and congressional testimony suggests that the oil companies used the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait as an excuse to raise gasoline prices without justification. The price gouging has forced state governments to cut essential services and has driven many consumers to give up food, medicine, and other necessities to heat their homes and get to work.

“The oil companies have the American public in a stranglehold,” says Edwin Rothschild, energy policy director for Citizens Action in Washington, D.C. “Any time there is any kind of explosion, accident, or disaster, we get these kinds of price increases.”

Panic and Profits

Shortly after the Iraqi invasion, oil companies and some media analysts tried to excuse the sudden hikes in gasoline prices by explaining that the invasion threatened Mideast oil supplies. An oil shortage would mean less gasoline, and less gas would fuel higher prices.

Such a shortage never occurred. According to the U.S. Energy Department’s Energy Information Administration (EIA), Iraq and Kuwait provide only eight percent of the world’s oil and less than five percent of what America buys — and all of it was quickly replaced by increased output from Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, and other oil producers.

Even if the Iraqi invasion had jeopardized supplies, it would have been a long time before Americans suffered an oil shortage. U.S. oil companies were sitting on a vast stockpile of gasoline. According to an EIA report, “Crude oil stocks at the end of July 1990 were the highest in nine years.” The 90 million surplus gallons could have replaced any loss of oil from Iraq and Kuwait for 120 days.

What’s more, the federal government is sitting on another 590 million barrels in the Strategic Petroleum Reserves, an underground liquid bank established in 1975 to guard against disruptions in oil supplies. So why did gas prices soar when there was no real shortage, and when Americans had already paid billions for a petroleum reserve?

The short answer is simple: panic and profits. Because oil suppliers and buyers feared there might be a shortage if Saddam Hussein bombed Saudi oil fields, the wholesale price of crude shot up. “What we are seeing is that the whole market has been taken over by fear and panic throughout the entire system,” says Phil Chisholm, executive vice-president of the Petroleum Marketers Association.

Fortunately for the companies Chisholm represents, retail gas prices — what you pay at the pump — are now pegged to the wholesale price of crude oil sold each day on the spot market. Whenever the wholesale price goes up, oil companies automatically raise the retail price for everything they have on hand — even the stuff they bought and began refining weeks earlier. “The rising price of oil has an instantaneous effect on the market,” admits Glenn Tilton, the Texaco executive.

It’s as if a grocer suddenly raised the price of all the cabbages in his store because he just learned next year’s supply will cost more. According to Edwin Rothschild of Citizen Action, that’s exactly what Exxon, Texaco, and others did with the more than 300 million barrels of oil they had on hand on August 2. Even though that supply cost them an average of only $18 per barrel, they based its retail price on the post-invasion price of $28. Rothschild estimates the companies pocketed $3 billion by using this system of pricing.

Although oil companies are quick to raise prices at the pump when the cost of crude goes up, they’re slow to pass the savings on to consumers when their costs go down. It’s strictly heads the oil company wins, tails the consumer loses. “Companies use the spot market as a reference point when prices go up,” says Rothschild. “The difference is when the price comes down, there is a long, long delay when those spot prices are not translated to consumers.”

To further insure their profits, the oil companies also contract for future supplies at a fixed price they believe will beat what they’d have to pay if they waited until the day of delivery and bought the oil on the spot market. Speculators and big oil consumers, such as airlines and chemical firms, play this futures market with the oil companies. Each party buys and sells contracts, gambling on what the price of crude oil will be on a particular day of delivery.

Like the pricing system, the futures market allows oil companies to exert more influence over a commodity they can’t quite control the way they did before the oil embargo of 1973 and the dawn of OPEC. “If they start buying and bidding up the wholesale price,” Rothschild points out, “they are in reality increasing the value of their lower-cost inventories.”

The system paid off in a big way in 1990. In the midst of the worst recession in years, the major oil companies announced fourth-quarter profits totaling almost $2 billion more than their earnings for the same period in 1989. Fearing public outrage, the companies dismissed the gains as a fluke and used a wealth of accounting tricks to hide even greater profits. Kenneth Derr, chairman of Chevron, called his firm’s $481 million windfall “an anomaly.”

Other businesses tied to the industry say the profits prove that rational “free market forces” have little to do with the way prices are set. “There is absolutely no competition on the wholesale level — I repeat, no competition,” says William McGilacuddy, president of the Virginia Service Station Dealers and Auto Repair Association. “Service station dealers across the country are tied to their refiner to buy the product from that refiner at the price that refiner sets.”

Even federal lawmakers, who tend to favor the profitable opportunities offered by free enterprise, were outraged. “The oil industry of this country is plundering us,” charged Senator Joseph Lieberman, a Democrat from Connecticut. “Perhaps the time has come for economic sanctions against the American oil industry.”

Schools and Shortfalls

The consequences of price gouging at the pump have been especially hard in the South, where a greater proportion of the population live in rural areas or in cities lacking adequate public transportation systems.

The price hikes have caused budget shortfalls in many states, forcing government agencies to cut comers or seek additional funding for gasoline:

▼ In Louisiana, state agencies have spent an extra $2 million on gasoline since August. The state school board is also seeking additional appropriations to compensate for a $4 million shortfall caused by the price hikes.

▼ In North Carolina, which is already scrambling to cut comers because of a $360 million revenue shortfall, the state school board says it needs an extra $3.5 million to make it through the school year.

▼ In Mississippi, Rankin County schools watched their fuel bill double as

they bought gasoline to bus 10,000 children from rural areas each day. “We’ve had to take money away from other sources,” says Kenneth Bramlett, assistant school superintendent. “Now we can’t repair the roof of one of the schools, and we have to put off building new classrooms.”

“No Gas in the Car”

Across the region, Southern families have also been hard hit. According to a 1988 report by the EIA, Southerners buy more gasoline than drivers in any other region of the country, consuming an annual average of 60 gallons more per vehicle than Northeastemers.

For working families in the energy-dependent South, gasoline price hikes are more than just an annoyance. The South is the poorest region in the country, and studies show that nearly three-fourths of the Southern poor rely on cars to travel. Price gouging by the oil companies has robbed them of basic necessities, jeopardizing their health and well-being.

Lillie Mae Ervin, 57, knows first-hand how months of gas price hikes can make it tough just living from day to day. Her family of three already struggles to get by on a meager income of $366 a month. When gas prices jumped last August, her gas bill doubled to $20 a week, forcing the Ervins to forgo their prescription medicine to buy fuel.

“Right now we have medicine over there at Super D that we can’t buy,” says Ervin, who lives 10 miles from Jackson, Mississippi. “There’s about three or four prescriptions there for blood pressure and other complaints. It’s just a hardship.”

If she doesn’t take her medicine, Ervin says, her head hurts and she feels dizzy. “I told my doctor, and he said it’s dangerous if you don’t take it.”

The Ervins are not alone. According to a recent report by the National Council of Senior Citizens, 5.8 million elderly households live at or below the poverty line. The report adds that when the cost of housing, food, and home energy are deducted, the average low-income elderly household “has less than $10 a week for clothing, medicine, transportation, and other necessities.”

Rubye Johnson, who founded the Wateree Community Actions center to help residents around Sumter, South Carolina, says the gas price hikes have made it harder for the elderly to take care of themselves. “Believe it or not, a lot of elderly aren’t even bothering getting food stamps,” she says. “They only would get $10 or $15 worth a month, and they would spend that much in traveling to pick them up.”

Even young Southerners who are able to work for a living are finding that with the gasoline hikes, they are barely making enough to survive. Susan Oliver runs a day care center out of her home in Shreveport, Louisiana, and her husband is a car mechanic. Price gouging has forced them to put off buying groceries and other necessities — and sometimes they still don’t have enough left over to buy gasoline.

“A couple of weeks ago, I had to cancel my son’s doctor appointment, because I had no gas in the car,” Oliver says. “I didn’t want to do it, but I had no choice.”

Oliver says she is angered by the huge profits the oil companies have reaped. “I think they should find some way to give some of it back to the consumer.”

Drilling Deeper

To help families like the Olivers and Ervins who have been hurt by unfair gasoline prices, federal lawmakers introduced a bill on February 5 that would keep oil companies from gouging consumers. Under the proposed legislation, large energy companies would have to pay a surtax based on all “excessive profits” that are 40 percent above their average net profits for the preceding five years. Senator Joseph Lieberman, who co-sponsored the bill, suggested that extra revenue could be used “to help pay for Operation Desert Storm or energy assistance programs.”

But oil companies have a different solution. The problem, they say, is environmental regulations. The industry wants Congress to lift drilling restrictions in environmentally sensitive areas, replacing foreign oil with domestic crude.

“We can permit the production of oil off the California coast,” Charles Dibona, president of the American Petroleum Institute, suggested at a congressional hearing last August. He also proposed that Congress “open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and Alaskan oil reserve” and permit drilling “especially in areas which already have been leased, such as those off North Carolina.”

But some say that the price hikes and war in the Persian Gulf underscore the need for an alternative energy policy that will decrease our dependence on oil, both domestic and foreign. Rubye Johnson, who founded Wateree Community Actions, recalls the gas hikes of the 1970s. She also recalls her response: “I designed a public transportation system and then got it approved. There are bus routes now picking up people in rural areas.”

More mass transit would be one step toward a meaningful energy policy. Some studies even suggest that building fuel-efficient cars might have averted war in the Persian Gulf altogether. According to the Rocky Mountain Institute, requiring automakers to build cars that get 31 miles to the gallon, rather than the current average of 19, “would end the need for any oil from the Persian Gulf.”

A good alternative energy policy would also promote the use of natural gas while developing solar and wind energy for heating and electricity. Such developments would reduce the dependency on foreign oil supplies that have pushed many people close to the edge.

But instead of trying to reduce dependency on oil, President Bush has followed the same line of thinking as his friends in the oil industry. The administration has called for more domestic oil production in Alaska, California, and the Outer Continental Shelf.

“I think the administration is really looking backwards,” says Jim Price, director of the southeast office of the Sierra Club. “It’s trying the same tired approaches that have led us into the situation we are in now.”

Price and others warn, however, that an alternative energy policy alone is not enough. Without a coherent foreign policy, they say, the war in the Persian Gulf will not be the last time Americans are expected to sacrifice their lives for oil, either at home or abroad.

“The oil companies have us between a rock and a hard place. There’s no way to win,” says Dorothy Brooks, a 23-yearold student in Bunnlevel, North Carolina, whose husband was sent to Saudi Arabia to fight. “My husband swore to protect America and its Constitution. But he didn’t swear to protect money. If he dies over there, I hold the oil companies, the president, and everyone who got us in this war to blame.”

Tags

Laurie Udesky

Laurie Udesky has been a reporter and editor for more than 25 years, reporting on mental health, social welfare, health equity, and public policy issues. She is a former associate editor of Southern Exposure, the print forerunner of Facing South.