This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 1, "The Golden Child." Find more from that issue here.

Annie didn’t have a mean bone in her body.

Walter said it looked like bones were all she did have as skinny as she was.

She was about twelve when we moved in next door. Right off she acted like she’d been knowing us. Her sitting outside looking after a yard full of boys who hardly minded a thing she said, and from the beginning she did Roy and me just like them, saying motherish things to us too, like the queen of backyards, her skinny self dashing around, looking into everything that goes on.

“Don’t eat nothing until you wash your hands. Keep away from that hornet’s nest. Go ask your Mama do she have any more boiled peanuts and see can we have them? Why that boy always wearing them hot boots?” Like that. Me and Roy liked Annie right away. She was bossy exactly like a real mother and she was only twelve. If I was her I wouldn’t claim those wild brothers of hers, especially not Skippy, who was dedicated to starting trouble.

Once he put a snake down the back of Annie’s shirt when she was out in the yard. She screamed for one hour. She screamed long after that snake fell to the ground and scrambled off. Nobody could get her to stop. Melvina and Mother went tearing up to Melvina’s house to see what was wrong and then Melvina whipped Skippy with all of us watching. She whipped him hard. “If you ever do that again you’re going to jail,” Melvina said. “You can be sent to jail for causing somebody to have a heart attack.”

Skippy didn’t cry, but Annie kept crying the whole time. Just thinking about that snake touching her skin made her flinch and jerk her shoulders. Mother felt so sorry for Annie that she let her come down to our house and eat Vienna sausages and a banana popsicle.

Skippy said it wasn’t fair and tried to make me go get him a popsicle too. “As soon as hell freezes over,” I said.

It seemed like Melvina being our maid was not enough. She wanted Mother to get Annie to hang out the wash or do the ironing. Something Annie could get paid for.

“Annie’s got enough of a job watching after that yard full of children while you come down here and work, Melvina,” Mother said. “If Annie needs to be doing something, she needs to be going to school.”

Me and Roy knew Mother’s education speech by heart, how the educated person didn’t have to be afraid, how the educated person can change things. When she started talking about education is the answer to everything she got on everybody’s nerves — bad. Me and Roy and Melvina hated it. Everybody hated it.

“I can’t keep the girl in a pair of shoes,” Melvina said.

“If Annie had an education she could buy herself all the shoes she wanted,” Mother said. Me and Roy gagged and rolled our eyes. “If Annie had an education she could change the world.”

“You educated,” Melvina said to Mother. “I don’t see you changing nothing. If it’s the same to you I’ll let somebody else’s girl change the world.”

Mother thinks it is pathetic that Melvina cannot see the value of a good education. “Lack of education is what’s holding the colored back, Melvina. Can’t you see that? I swear, you can’t see the woods for the trees.”

“I ain’t trying to see no woods,” Melvina said. “I’m trying to get out the woods. Chopping down one day at a time.”

“What about the big picture, Melvina? What about tomorrow?”

“I got today standing in the way of tomorrow,” she said.

Which is why it was a paying job Melvina wanted for Annie. Nothing less. We are just regular white people, but Melvina acts like there is no end to the money we got. She wants Walter to pay Skippy to mow the yard, and Alfonso Junior to clean pine straw out of the gutters, and Orlando to pick up the pecans in the yard. Walter never will do it though. So Mother is Melvina’s only hope. Since Mother went to FSU for two years she is more educated than Walter and acts accordingly. Walter says Mother majored in changing the world when secretarial school would have done her more good. But Mother takes her education seriously and Melvina knows how to make her prove it.

Melvina hit on the idea of Annie babysitting me, Roy and Benny some night when Mother and Walter went out. But Mother and Walter never went out. Not without taking us. Every blue moon they might go eat at the Elks Club. Once, right after they got married, on Mother’s birthday, Walter took her all the way to the beach at Alligator Point to the Oak’s Seafood Restaurant, and our granddaddy came down from Alabama to stay with us.

But once the idea took hold Melvina started saying, “A man like Mr. Sheppard ought to take his wife out once in a while.” And Mother started to believe it too. “Mr. Sheppard makes good money, don’t he?” Melvina asked. “He can afford it, can’t he?” and pretty soon Mother had taken up the cause — Annie babysitting for us one night while she and Walter went some place nice.

Nobody asked me and Roy and little Benny what we thought about the idea, but Walter didn’t think much of it. “Annie’s no babysitter,” Walter said. “She don’t have sense to come in out of the rain.” So Mother argued with him. “I’m not sure that girl is all there — not entirely,” he said. And Mother argued. “She doesn’t even know how to use the telephone,” he insisted.

“I’ll show her,” Mother said. “I’ll write down the fire department, and the police, and the hospital numbers and set them right beside the telephone.”

“I don’t like nothing about this,” Walter said and then gave up.

And you never saw such a to-do made over anything like Annie babysitting us. “She’s not going to boss me around,” is all Roy said. “She can babysit if she wants to, but I don’t have to mind a colored girl, do I, Walter?” Walter made a noise in his throat and left the room.

Mother made Annie come down to our house and practice on the telephone. About one hundred times she called the Tallahassee Bank and Trust to listen to their recorded advertisement and get the correct time. Finally Annie said she could dial the number with her eyes closed and Roy, Mother, Melvina and me stood around and watched her, and sure enough, she COULD dial it with her eyes closed. Then Mother wrote out the emergency numbers and scotch-taped them beside the telephone. She drew a little fire beside the fire department number and a little bullet beside the police number. “Just in case,” she said.

When Skippy heard about Annie babysitting us he got one of his stupid ideas. He said as soon as Mother and Walter left home for us to let him and Alfonso Junior and all the rest of their brothers come in the house to look at television. He said they will watch for Walter’s car to go off down the road, then they will come down to our house and for us to let them in.

Annie got mad and said she was not going to do any such thing. “Babysitting is a paid job and I’m going to do it like a paid job,” she said.

“We ain’t gon hurt nothing,” Skippy said.

It was the craziest idea I ever heard. We cannot have a house full of colored people with Mother and Walter not home. Not colored boys all up in our house.

“No sense in you keep asking,” Annie said to Skippy.

“We ain’t gon hurt nothing,” he said again.

“That’s right,” Annie said. “You ain’t gon hurt nothing because you ain’t gon be there.”

“One colored person is all right,” I explained to Skippy, “but it can’t be a bunch of them. Don’t you see? A colored girl is all right, but colored boys cannot go around in people’s houses.”

Skippy ignored me. “Tell him, Annie,” I said.

I stood there thinking about it. I do not even know how colored boys look on furniture. How do they look in an indoors room? I tried to picture it, me and Roy sprawled out to watch a little television with Annie and a room full of moving around colored boys, stepping over us on the floor, sitting here one minute, there one minute, picking up everything we have to look it over, setting their bare feet up on everything, handling everything. What if they decide they will go off with some of our stuff, like they unplug a nice lamp and walk out the door with it, or Skippy shoves Walter’s favorite chair across the floor and squeezes it out the door and hauls it off. Who will stop him? Who will say, “Skippy, you put that chair back. You know better than to go off with a chair that doesn’t belong to you.”

So it won’t do. Annie has to tell him.

“We are just as sorry as we can be,” Annie says, her hands on her hips, “but you cannot come in that house to watch TV.” Annie turns into the Queen of England telling it. Her part is grand. Yes, I will be in those white people’s house eating some of their supper, drinking their cold drinks, bossing their kids, watching TV, and making all matter of important decisions. “You mize well forget it,” she tells Skippy.

“You gon be sorry,” Skippy says.

“If you come around, I’ll let you in,” Roy tells Skippy. “I don’t have to mind a colored girl.”

Roy needs his mouth taped shut. I tell Mother that all the time.

On Saturday night Mother and Walter get all fixed up and go off with some friends of Walter’s that work at the highway department with him. They go to eat catfish at a new catfish place close to Lake Jackson. Mother has Benny asleep in bed before they leave so Annie just has to watch Roy and me. Mother says for us to turn on the TV and sit in the living room and watch it. She kisses us and says, “Go to bed when Annie says to and behave yourselves.” We say ‘yes ma’m’ and she hurries out to where Walter is sitting in the car waiting, with a necktie on.

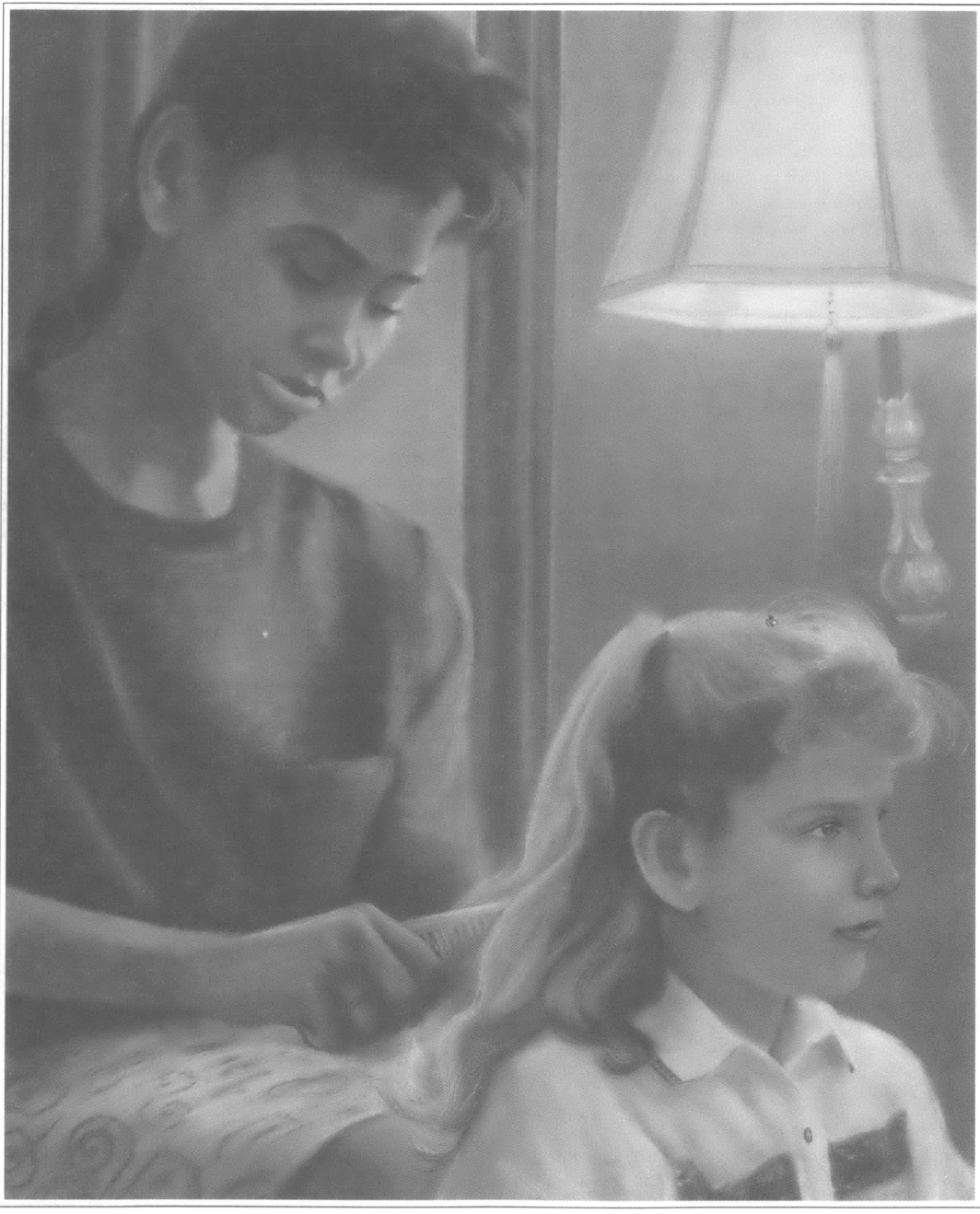

Annie is just smiling and smiling. Us too. Annie gets us like that just by doing it herself, smiling. Melvina has plaited Annie’s hair real nice. And Annie has promised she is going to put braids in my hair, she’s good at it, making me crazy-looking hair-dos. Plaits everywhere, like colored girls.

It isn’t dark yet when she first gets there, but we stay inside anyway and watch TV like Mother said. It was the Jack Benny night, with Rochester. Annie sent me for a comb and sat there combing through my hair, getting the tangles out.

“Your hair don’t want to do nothing but lay down flat on your head,” she said.

“I know that,” I said.

After a while Annie fixed us some peanut-butter crackers and everything was going good. Roy was lying up on the sofa in his boots and cowboy hat eating his crackers Roy Rogers style. I was sitting on the floor and Annie was sitting on a chair behind me starting on my hair-do and saying my hair is too slick to do nothing with — when the doorbell rings.

It was the first we had noticed it was dark outside.

“Go see who it is,” Roy said.

Now even though there was a street light out by the road, all the way around the house was just woods in every direction.

“Who’s at the door?” Annie asked us.

“We don’t know,” we said. “How should we know?”

But the truth is we were all three thinking the same thing. We were thinking it was Skippy and Alfonso Junior and every other colored boy in Tallahassee lined up out there to get in our house and watch Jack Benny.

“Answer the door,” Roy said again.

“I’m going to kill Skippy,” Annie mumbled. She slowly opened the door that led out to the porch. We couldn’t see a thing. Me and Roy were one step behind Annie while she walked all the way to the porch door, rattled it, and said to us, “You ought to have a latch on here.” Rattled it some more and said, “Nobody’s here.” We filed slowly back into the house. Jack Benny was joking with Rochester on TV. We felt kind of glad to see him.

About the time Annie got the door closed good the doorbell rang again. “Who’s there?” she yelled real loud.

No answer.

“Who is it?” she yelled again.

Still no answer.

“It’s Skippy,” I whispered. “You can’t let him in, Annie.”

“Skippy?” she hollered, “You get away from here.”

Roy and me were getting excited. We snuck over to the window and poked our heads out the curtains, our noses pushed up against the glass. It was too black to see anything.

“Lock the door, Annie,” we said. “In case they try to bust in.”

Annie looked at us like we were stupid. “I already locked it.”

Then Roy bellows out the window, “Skippy, if you want in this house come around to the back door and I’ll let you in.”

There was no answer so Roy hollered again, “You can come in this house if you want to.” But there was silence for the longest time until Roy gave up and sheepishly turned to face me and Annie. “He can come in this house if he wants to,” he said.

“Shut your stupid mouth, Roy,” I said.

We waited what seemed like a long time for something to happen.

“Why don’t he come?” Roy whispered.

“Because,” Annie said. The way she said it gave me and Roy the creeps. She looked so serious, like she knew more than she was telling. “We got to turn off the lights so they can’t see in,” she said, and right then she snapped the TV off. Me and Roy grabbed her hands. The three of us shuffled over to the one small lamp that was still on, but Roy and me clung so tight to Annie that she couldn’t get a hand loose to turn it off. “Let go, you fool,” she whispered. Roy let go of her hand just long enough for her to flip the switch.

Then complete darkness. That darkness that has little spurts of color shooting through it. Quiet. We listened until the quiet started blaring. It sounded like crickets surrounding the house had gone hysterical.

“Go lock the back door,” Annie told Roy, but he was too scared to do it, so we all three moved to the kitchen like a stuck together statue. Our feet did not lift up off the floor. In the kitchen Annie pried loose from us and while we clung to her clothes she turned the lock on the back door. Relief went over us.

Then we heard footsteps and a sudden pounding on the back door. KNOCK! KNOCK! KNOCK! right at our faces. All the air went out of the room like it does at a swimming pool when you go under.

“Make him quit it, Annie,” I said.

“It’s Skippy,” Roy said. “Let him in,” and he reached to unlatch the door.

“Wait!” Annie ordered. She tilted the edge of the kitchen curtains to look out. Nobody was there. Nobody. “It’s not Skippy out there,” she whispered.

“It’s got to be,” I said. “Who else. . . ?”

“It ain’t him,” Annie said. Me and Roy tried to make out Annie’s face in the dark. “Skippy would not be messing with his chance to watch TV,” she said. “If it was him he’d be in this house by now. Nobody wouldn’t have to ask him twice.” Her face was serious.

Me and Roy froze. We like to know EXACTLY what it is we are afraid of.

“But it’s got to be him . . .” I said.

“No such thing as got-to-be,” Annie said. Her voice was very quiet. “How do you know it ain’t white men heard I’m keeping y’all by myself and come to get me? How you know it ain’t some crazy body seen us in the window? It could be any crazy body out there.”

Me and Roy listened. Annie made good sense in complete darkness.

“It could be drunk niggers trying to break in this house,” Roy said, wild-eyed.

“It might be somebody escaped from Chattahoochie,” Annie said.

“Or broke out of jail,” Roy said. “Convict off the chain gang. Or anything.”

“We got to hide,” Annie told us.

“Yes,” me and Roy whispered, “let’s hide. We got to hide.”

“Call the police first, Annie,” I whispered.

“You think I’m crazy?” Annie said. Her voice was scaring me too.

“Please,” I begged. “Mother wrote the number . . .”

Annie clamped her hand over my mouth, her eyes shooting right into mine. “I may be scared, but I ain’t crazy,” she said. “Not that crazy.” Her words were sharp as a pocketknife.

At Annie’s command we caravaned into my bedroom and crawled up under the bed — all three of us — with Annie in the middle. We lay on our stomachs, flat and still. Twice Annie caught one of her plaits on a wire hanging from the bed springs. Both times her head was caught from the back, she couldn’t turn to either side. She was stiff necked until me and Roy fumbled around in the dark and unhooked her from the rusty wires. It hurt, but Annie didn’t cry. “It’s okay,” Roy told her, “just keep your head down like this.” He rolled his head from side to side on the wood floor.

The bed skirt hung down and covered us up. There is something nasty about lying underneath a bed skirt in the dark. “Can’t nobody see us now,” Annie said.

We lay there in silence a few minutes. Then I start thinking about the world coming to an end. Anything could happen. The Russians could drop a bomb on Tallahassee. Lightning could strike the house. Poisonous snakes could slither out of the hall closet and bite us. And I am suddenly aware I have never been the good person I always meant to be.

“I love you, Annie,” I said. “You know. In case we die. I love you too, Roy.” Then Annie said out loud that she loved me and Roy too. It was easy to say, lying under abed in the dark. But Roy wouldn’t say it.

After the floor started to get hard Annie made Roy scoot out from under the bed and get us a pillow so we could lay our heads down better. She got him to do it by telling him how brave it would be and how it would mean he had more guts than both of us — him being a boy and us just being girls. At first he said he wouldn’t. He said why didn’t Annie make me do it since I was older. But then we said, “Would Roy Rogers make Dale Evans climb out and get the stupid pillow?” And Roy did it.

We lay there in terror. The dizzy kind. The kind that feels like a bird is set loose in your belly, flapping its way through your insides. I’m scared because I think a bunch of colored boys might get in the house and do who knows what. I think of drunk niggers in the flower beds looking in through the windows, and carrying knives in their pockets and wearing scuffed up, raggedy shoes. They try to kill me with smiles on their faces and their white teeth showing.

Annie is mostly scared of white men. It doesn’t have to be a bunch of them, it can be just one. One crazy white man lurking around in the night, looking for a colored girl he has heard is babysitting white kids for the first time in her life, and him coming after her with soft pink hands and a red face and probably a tattoo on his white belly. And in his pocket he has got chewing tobacco and keys to his tore up pick-up truck. Tears go down her face telling it.

“I heard about this colored girl walking down the road one time, not bothering anybody,” Annie says, “and a white man stops his truck and says does she want a ride?” Annie is telling this slow and quiet. “The girl got in that truck and vanished from sight,” she said. “Nobody ever saw her again until they found her body floating face down in Lake Jackson.”

Me and Annie hold hands now. Tight.

“That’s nothing,” I tell her. “I heard about this colored man that killed a white girl and didn’t know what to do with her body. He didn’t have time to dig a deep grave. So he got a saw and sawed off her arms and legs, sawed her all up into manageable pieces and just scattered them out all over the place.”

“He did not?” Annie said, squeezing my hand.

“He did too,” I said. “People are still finding her pieces. And she couldn’t get a decent funeral since all her body wasn’t collected. And nobody could prove nothing, so the man is still on the loose.” My voice shook.

“The police didn’t catch him?” Annie whispered.

“No,” I said.

“And he was colored?”

“He sure was.”

“Then why didn’t they catch him?”

“Don’t ask me,” I said.

Then Annie said, “One time I knew this real pretty girl that white men got ahold of. They doused her with kerosene and set her on fire. She started running and everything she touched caught fire too. She caused an entire house to bum down and left two white men burned so severe they went crazy and had to check in at Chattahoochie.”

“Is that the truth, Annie?” I said. “Do you swear that’s true?” It scared me so bad just to hear it because I am more scared of fire than anything. That’s the main reason I don’t want to go to hell. Because you just keep burning in a fire forever and nobody comes to put it out. “Do you swear to God that’s true?” I said again.

“It’s as true as this world,” Annie said. “It’s so true they made the girl’s Mama pay for the house she burned down. She’s got to pay on it the rest of her life.”

I pictured myself in flames, running through a dark Tallahassee night when everybody is asleep, going through yards like a blazing torch, dogs after me, barking and trying to bite. I pictured colored men pouring bottles of whiskey on me and laughing at the way the flames shoot up, while I run in circles.

“You know what some white men will do if they get ahold of a colored girl?” Annie said very quietly.

“What?” I say.

“Take her clothes off.”

“Then what?” I ask.

“They bother her,” Annie whispered.

“SHUT UP! ” Roy says.

“Y’ALL SHUT UP!”

It got hot up under that bed with our heads bunched together on the pillow. It was like an oven, our breath heating things up, making us sweat, but even so the three of us lay with our legs tangled together, Annie’s skinny arms wrapped tight around me and Roy. And ours around her. We were quiet for a long time.

Our fear carried us just as far as it could before flipping itself over. Soon we were all dead asleep.

I was dreaming about Rochester. It was dark and he was chasing me through the woods behind my house, smiling. I knew if I could just get home to Jack Benny he would save me, so I was desperately running to the TV set in my house. But when I got there Roy tried to lock me out. He had tied Annie up on the sofa and she was crying. He tried to kick me with his Roy Rogers boots, but I pushed him out of the way and ran to turn the TV on. I was safe. I was safe. But no Jack Benny. Instead, Skippy was on the screen. He was sitting in a chair exactly like Walter’s favorite chair, lighting matches and blowing them out. He smiled at me and then I heard Rochester’s footsteps coming in the house after me. . .

I woke up to the hammering of feet on the hardwood floor and the sound of voices ricocheting through the dark house. “What the hell?” The voice set off an alarm in my blood. It was Walter’s booming voice. Walter and Mother were home. I scrambled out from under the bed. Annie did too, but Roy stayed put, asleep as a rock.

“What the hell?” Walter shouted again, as Annie and me groped our way to the hall just as Mother switched on the light. A flood of yellow poured over us as we rushed toward Mother’s voice. At the sight of us she let out a shriek, “You scared me to death hiding like that. All the lights off.”

Walter went in and dragged Roy out from under my bed by his leg and carried him to his room and put him to bed. Roy never woke up.

Annie and me wanted to explain to Mother, but she just kept saying things like, “Always leave on a light.”

“Yes, ma’m, but . . .”

“At least one light,” she said. “The front porch light at least.” Mother walked around the living room switching on all the lights as if we needed the example to know what she was talking about.

Walter walked back into the living room and Mother said, “Walter, pay Annie and let her get on home.”

“Do what?” he said.

“Pay her, Walter. We have to pay her.”

“I’m never babysitting for y’all again,” Annie said.

“Well, now,” Walter said. “That sounds like something worth paying for.”

“Nobody is safe over here,” Annie said.

“Somebody was trying to get in the house,” I said.

Walter looked at Mother like he had won a bet and she owed him money. “Is that right?” he said. “And I suppose you don’t have the foggiest idea who it could be?”

“We thought it was Skippy,” I said. “But it wasn’t.”

“Scaring you and Annie is Skippy’s idea of fun. That’s all,” Mother said.

“But it wasn’t him,” I said.

“Walter, you need to talk to Skippy tomorrow and put an end to this foolishness,” Mother told him.

“It wasn’t Skippy,” I said again.

“I’m going to tell Melvina first thing tomorrow morning. She’ll get Skippy straightened out,” Mother said.

“But it wasn’t Skippy,” I repeated.

“It could have been any crazy body,” Annie said.

“It could have been white men coming after Annie,” I said, “or . . .”

Walter’s eyes slapped my face. “Say what?”

“White men,” I said.

“Don’t let me hear you talking nonsense,” Walter said.

“Lucy, don’t be silly.” Mother reached for Annie’s hand. “You need to be getting home, Annie,” she said. “We’ll get this straightened out tomorrow.”

Annie pulled her hand away from Mother’s and folded her arms across her chest like a roadblock. “I’m not walking through the woods by myself,” she announced. “I had a scary night and I’m not going through them woods.”

We all looked at Walter.

He did his jaw like he does right before he spits tobacco juice. “Oh hell,” he said, stomping out of the room. “Let me get my flashlight.”

“You forgot my money,” Annie yelled as Walter went down the hall. “You gon pay me, ain’t you?”

Annie grabbed my arm and squeezed it when Walter came back with the flashlight. “Come with me,” Annie whispered. “You got to. Please.”

“Annie, there’s nothing to be afraid of,” Mother said.

“Lucy, you go to bed,” Walter ordered.

“I want to go with you.”

“You heard what I said,” Walter barked.

“Lucy, you mind Walter,” Mother said, pulling me back from the door. “He’s mad enough already,” she whispered.

Mother and me stood at the picture window and watched Walter and Annie walking through the night, flashlight bouncing in front of them as they went. Annie’s hand was on Walter’s elbow. If Annie had had on a dress they might have been going off to the prom. Twice Annie looked back at the house trying to find my face in the window.

Walter is not as mean as he acts I wanted to scream. I’m pretty sure of it. But the night was so black. Walter’s flashlight seemed like a tiny sword of light slicing sharp and useless, making nervous zigzags in the darkness.

“This is not a safe world,” I told Mother.

“If you get a good education you can change the world,” Mother said.

“Why can’t I go with them?”

“Because,” Mother said, “Walter said you couldn’t, that’s why.”

“Why are white men after Annie?” I asked Mother.

“That’s crazy,” Mother said. “Walter’s a white man. Your Granddaddy is a white man. They’re not . . . Lucy? where are you going? Lucy, come back here!”

I was on the porch, down the steps, and halfway across the yard before Mother quit calling me back. I ran after Walter and Annie who were nearly to the road. They stopped and turned around to face me, Annie’s arm was looped through Walter’s now making them look like a couple of people about to walk down the aisle together. Walter shone the flashlight right in my face.

“Where do you think you’re going?” Walter said.

“With you,” I answered.

I know deep down that Walter is not that mean. If he was mean, would Mother have married him? Would he take Mother to eat catfish wearing the necktie she gave him for his birthday? Would he pull Roy out from under my bed and carry him to his room? Or pay Annie fifty cents for babysitting us? Walter is just a regular white man. He does not go around hurting people on purpose. Not even colored people. I am almost certain of it.

“I guess if I want you to mind me I’m gon to have to start talking with my belt,” Walter said, holding the flashlight right up to my face making me close my eyes.

“No, sir,” I said.

“Didn’t I tell you to stay home?”

“Yes, sir. But I have to go with you.”

“Why?”

“Because, you’re a white man . . .”

“What?”

“And Annie . . . she don’t . . . ” I looked at Annie who nodded me on, “and Annie is scared of white men.”

“At night,” Annie said. “I ain’t scared of nobody during the day when I can see good.”

“And you’re mean to her,” I said.

“Mean?” Walter said. He shined the light in Annie’s face now. “Gal, have I ever been mean to you?”

“Yes sir,” she said. “All the time.” And she grabbed my arm and started running up the road to her house pulling me along with her. “Hurry,” Annie said, “before he comes after us.”

And we ran hard, but Walter didn’t follow. He stood in the road yelling, “Lucy, get yourself back here right now if you know what’s good for you,” and painting us with flimsy strokes of flashlight.

“He’s liable to get a gun and come after us,” Annie said, panting as she ran.

“No, he won’t,” I said. I wanted to say he didn’t even have a gun. But the truth was he had a revolver on the top shelf of his closet. Me and Roy had climbed up there and looked at it, but we have never seen him use it for anything except once when he shot a stray cat that bit Roy.

“You can’t be sure,” Annie said.

And she was right. None of us had ever seen Walter take a drink, but we all knew he kept a bottle of liquor in the glove compartment of his truck. We just pretended we didn’t know it. And he pretended he didn’t drink it. The same with his gun. Except for the day he shot the cat everybody in the house pretended the gun was not there. What else did we pretend Walter didn’t do?

“Lucy, don’t make me come up there after you,” Walter shouted. He had all but forgotten about Annie. “I’m counting to ten and you better be back here. One . . .”

We were in front of Annie’s house now. Melvina opened the door to see what all the noise was about. She was wearing a faded pink nightgown that she had cut the sleeves out of and her hair was tied up in a rag. I had never seen Melvina in her nightgown. She stepped out on the porch and fixed her hands on her hips. “What you think you’re doing running around this time of night?”

“Nothing,” Annie said.

“I got to go,” I said, turning to leave.

Then Skippy comes out of Melvina’s house too, stands on the porch, laughing.

“Hush your mouth,” Melvina says to him.

“Two . . . Three . . .”

Melvina looked at Walter standing out in the road. “Girl, you better RUN home! ” she said. “Don’t let that man stand out there calling you.”

“Don’t go,” Annie said. “He’ll whip you for sure.”

“He won’t,” I said.

“Four.”

“Walter’s not that mean, Annie,” I said. I looked at her face for some sign that she believed me. I want her to believe he is different from other white men — so I can keep believing it myself.

“Five . . . Six . . .”

“Get home,” Melvina hollered. “Don’t let that man come up here after you.” She was waving me on with her hand.

“I’m pretty sure he’s not that mean . . .” I said. I looked at the three of them standing together on the porch. “Hurry,” they kept saying, “before you make him mad.” They feel sorry for me. I can see it. And they scare me because they act like they know things.

“Seven, goddammit,” Walter shouts.

“Run!” Annie screamed.

I turned away, running as hard as I could toward Walter who stood in the middle of the dark road aiming the flashlight right square between my eyes.

Tags

Nanci Kincaid

Nanci Kincaid grew up in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Her first novel, Crossing Blood, was published by Putnam in June. (1992)