This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 3, "Sunbelt Blues." Find more from that issue here.

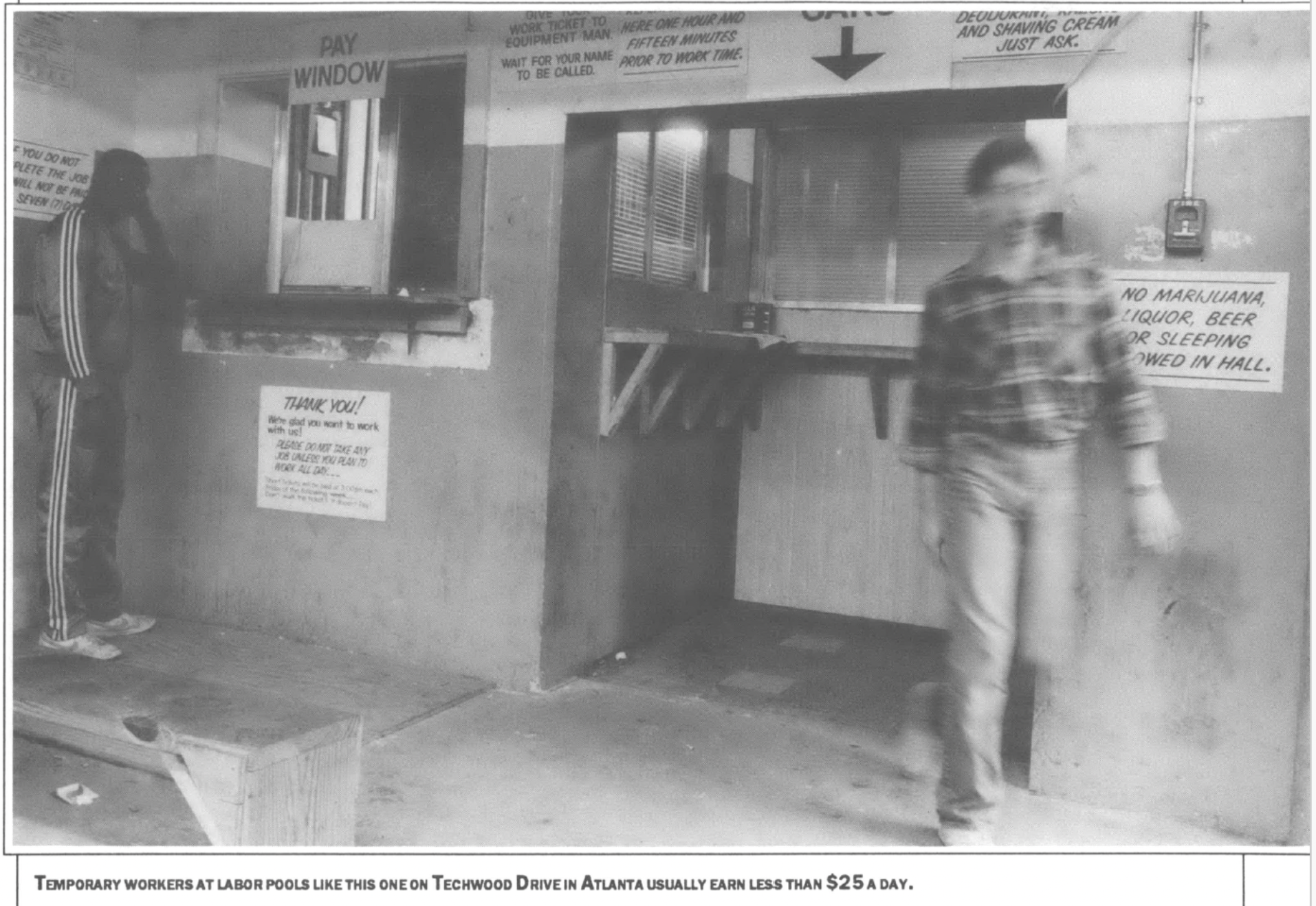

Atlanta, Ga. — It’s five a.m. and there’s little action in streets that snake like rivers around the gleaming steel, stone, and glass towers that harbor some of the South’s most successful and profitable businesses. But just blocks from the city center, the rubble-strewn alleys and dark streets between Techwood Drive and Simpson Street already buzz with activity.

Hundreds of men line up outside dilapidated storefronts. Drowsy and fatigued, many of them homeless, they struggle to shake off the effects of early wake-up calls at nearby shelters or long bus rides into the city.

Those who awake early are the smartest. They know if they get down to Techwood by six, they may snag a job at Labor World or Right Hand Man. They’ll earn $20 or so that day, just enough to scratch out a living.

Another day has dawned at the labor pools.

200 Men, Labor Pro, Industrial Labor Services, Peakload — these are just a few of the growing number of “temp agencies” known as labor pools that provide cheap, hassle-free, manual labor to the mainstays of corporate Atlanta.

The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, the Marriott Marquis hotel, and construction firms like Davis Mechanical Contractors routinely pay local labor pools to provide workers by the day. Unlike union hiring halls, which force employers to pay fair wages and benefits, labor pools offer no such comforts. Most pay only minimum wage, and few provide any benefits.

Temporary labor is nothing new, especially in the South. Ever since the plantation system gave way to sharecropping, the region has increasingly relied on migrant farmworkers to harvest its crops. But it is only in the past decade that the urban market for temporary manual labor has exploded into a multi-million-dollar industry.

The Georgia Department of Labor does not regulate labor pools, making official statistics hard to come by. But dozens of labor pools now operate within a three-block radius of Techwood and Simpson streets, sending out thousands of workers every day and keeping hundreds more on hold in filthy waiting rooms, ready to be called for jobs.

Those who frequent the pools say hundreds of companies have set up shop in the Atlanta area. Labor pools have also proliferated across the region — in Houston, Dallas, Orlando, Miami, New Orleans, Nashville, Charlotte, and scores of smaller Southern cities.

Business leaders and labor pool operators defend their practices as a way for those with no income and no chance at a full-time job to earn a living. But critics of labor pools, including the homeless and their advocates, say the system exploits the people it claims to help.

“It’s slave labor,” says Jerome Smith, an 11-year veteran of labor pools. “You’re a slave. They take you out on these jobs and then you’re doing crap—I mean really crappy work. And you say, ‘Man, I can’t believe I’m doing this kind of stuff.’”

Vans and Sandwiches

Labor pools provide manual day laborers to employers for a fee. A company in need of temporary manual labor simply calls a local labor pool and arranges for a crew to be brought out to the work site or factory. Instead of hiring a cadre of part-time, temporary workers, the company saves time and money by writing one check to the labor pool, which handles the payroll and covers unemployment insurance, workers compensation, and other expenses.

According to a report by the non-profit Southern Regional Council, companies pay an average of $7 an hour for each worker they use, with some fees running as high as $14 an hour.

Workers, on the other hand, generally receive only $4 an hour for their labor. Before they get their money, however, the labor pools routinely take daily business expenses directly out of their paychecks.

The labor pools deduct unemployment insurance and state and federal taxes. They subtract the cost of van transportation to and from the job site—as much as $2.50 each way—and often fine workers for lost hardhats, gloves, and boots. They even provide workers with a sandwich for lunch—and then deduct $2 or $3 from their paychecks.

After all the deductions and fees, a typical worker earns between $20 and $25 a day. Most get sent out on a job only three or four days a week, and only a handful earn more than $100 a week.

“The worst part is what they pay. Anyone will tell you that,” says Frank Trusty, who gets occasional restaurant and construction jobs through Industrial Labor Service. ‘They don’t pay you enough to get out. They pay you just enough to come back every day.”

Trusty, homeless at age 19, lives in the Rising Star Men’s Shelter. On the second-floor of the shelter, 150 men spend the night on thin vinyl mats spread out on a wooden floor. Some are already asleep by 6:30 p.m. Others wash their clothes or play cards in the corner.

Talk of labor pools dominates their conversation. Complaints about the way labor pools treat workers go beyond the low wages to the very core of the system they promote—an endless cycle of dependency and poverty that offers no way for those without to get ahead.

“It is so discouraging,” says Jerome Smith. “They’re not doing nothing that benefits anybody. They think they’re benefiting you by sending you on a job and then giving you $15 or $20 a day. They make more money than you make and you’re doing the work. Let’s face it, that’s disgusting.”

The work is hard, physical, and often dangerous. Smith recalls one job at an Atlanta construction site where he and a crew of other day laborers were sent into a pit to empty it of rainwater. While they worked, the sides of the hole caved in, sending Smith and the others scrambling to get out. Dozens of other homeless men—all veterans of the labor pool system—recount similar stories of dangerous, filthy jobs. One worker who wished to remain anonymous recalled being taken to a job at a rendering plant in south Atlanta that processed dead animals and spoiled meat into animal feed. He was given a rough

broom and made to sweep the rotting meat down a hole in the middle of a concrete floor.

In the summer, he says, the stench was terrible and men would pass out. Even those who could stand the smell would slip in the slime, becoming covered in the mess. After a day’s work, the men would be too filthy to ride public transportation. Many were forced to walk home, airing themselves out in the breeze.

All this, the worker says, for less than $4 an hour.

Payroll Tricks

Employers who call Labor World USA in Atlanta are greeted by a cheerful voice: “It’s a great day at Labor World! How can I help you?”

For Labor World—one of the largest labor pools in the nation — every day is a great day. Based in Boca Raton, Florida, the company operates 55 branches nationwide and expects to make $80 million this year.

Temporary work is big business for labor pool “chains” with franchises scattered across the country. Peakload Inc. of America operates 16 branches from its headquarters in Barker, Texas, and projects annual sales of $45 million.

No federal, state, or local regulations safeguard workers against labor pool abuses, and some companies reportedly take advantage of the lack of oversight to keep operating costs low and profits high.

Many labor pools pay their workers in cash at the end of each day, and the study by the Southern Regional Council found that the lack of paperwork allows labor pools to underreport the size of their payroll and pay less than required in state unemployment insurance.

Manual labor pools also keep unemployment costs to a minimum by always having a job available for workers who try to file claims. “Labor pools can always give somebody a job for a day—at least on the day they apply as an unemployed worker wishing to draw unemployment compensation,” says Steve Suitts, executive director of the Southern Regional Council.

Labor pools can get away with such abuses because of the relative helplessness of their poor, predominantly homeless workforce. Slowly, though, workers are starting to stand up for their rights. James Steal decided to fight back—and in doing so became the first day laborer in Georgia to successfully challenge a labor pool in court.

Steal sued Labor World, saying the company kept track of his hours on the work ticket of another employee and then paid him for only half the hours he actually worked. According to the suit, Labor World routinely used tricky payroll procedures to rob day laborers of a portion of their wages.

When the case came before Judge John Mather on June 20, representatives of Labor World failed to appear. The judge found the company guilty and awarded Steal $5,000—the maximum judgment allowed in Georgia state court.

Steal says that workers must continue to sue labor pools and press for regulations to curtail the abuses. “The laws that are on the books in this state concerning labor pools give them a blank ticket to do what they want to do,” he says. “And that’s why these people take advantage of us.”

Dollar a Trip

Labor pool managers paint a different picture of the services they offer. Hartley Wilson, a customer service representative for Right Hand Man, says that labor pools give workers a chance to make something of themselves.

“We try to be as fair as possible,” he says. “When we do find someone who is showing an effort to better themselves, that’s what we pride ourselves on. They can get themselves a raise, they can learn a skill—we’re not going to hold them back from getting a regular job.

“Wilson says Right Hand Man pays workers between $3.50 and $7 an hour, depending on the job. The Florida-based company also provides transportation to and from job sites for $1 a trip.

Wilson dispatches as many as 150 workers a day, most to factories or construction sites. He says he tries to screen each worker personally, letting them know where they ’re going and giving them a choice of jobs whenever possible.

Hartley would not disclose the fees Right Hand Man charges its customers. “The exploitation here is not what you think,” he says. “Of course, we are a business intending to make money.”

Wilson bristled at the suggestion that day labor is a form of slavery. “You can find a lot of bad in everything, but suppose there wasn’t a labor pool,” he says. “Where would these people be getting money if they really need it to buy their families food? I don’t see it as a form of slavery. They’re paid for the labor.”

Stop the Presses

Despite their differences, critics and proponents alike see the controversy over labor pools in economic terms. For companies who use temporary agencies, the system saves money. For those who do the work, temporary jobs rob them of the chance to earn a decent, stable wage.

“When you go out to the job, you’re doing an $8-an-hour job for $3.50 an hour,” says Frank Trusty at the Rising Star shelter. “The only reason they’re hiring from labor pools is they don’t have to pay the tax and insurance.”

Jerome Smith agrees. “The people at the company are walking around grinning and laughing at you knowing that they’re making $9 or $10 an hour.”

The Atlanta Journal and Constitution has a reputation as the biggest user of labor pool workers in the city. Vic Brown worked at the newspaper off and on for almost three years through a now-defunct labor pool called Tracy Labor.

“The newspaper is the main problem,” he says. ‘The Journal is the worst one. They use labor pools every day, seven days a week. Why can’t they just hire us to load trucks? We’ve been doing it for years. I know guys working at the Journal 10 years still making $3.50.”

Jimmy Easley, manager of bulk distribution for the paper, acknowledges that his department uses labor pool workers to load and unload trucks “basically on a daily basis.”

So why not just hire enough men to do the job? Easley says his deliveries vary each day depending on the number of inserts, making it difficult to know how many workers he will need. Hiring men from labor pools gives his department “flexibility.”

Jay Smith, publisher of the paper, says he is concerned about the exploitation of day workers. So far, however, the only action he has taken is to write the labor pools and ask them about their employment and pay practices—even though stories filed by his own reporters have revealed low pay and unfair working conditions.

At least one company has taken matters a step further. J. Barkley Russell, public relations manager for Westin Peachtree Plaza, says the hotel stopped using labor pools for banquet setups and other custodial tasks when it learned that workers were being abused. According to Russell, the company has opted to increase its own part-time staff rather than rely on labor pools for temporary help. Sandra Robertson, director of the Georgia Citizen’s Coalition for Hunger, says she is encouraged by such actions, but added that the problem goes beyond the labor pools. To Robertson, all temporary labor represents a system of economic enslavement that leads to more serious social problems.

“It’s a system that keeps people poor,” she says. “The system is designed to keep a supply of workers available to companies that are cheap, temporary, and expendable. In other words, when they no longer have a need for them, they don’t have to go through the hassle of laying people off or giving them severance pay.”

For workers, she says, temporary jobs put their entire lives on hold. “What

it does is make their lives temporary, everything is temporary because they never know if they ’ll have a job one day to the next. They don’t know how many hours they’ll work. Their future is very shaky — they can’t plan for any of the necessities of life.”

Bloody Gloves

Workers and advocates like Sandra Robertson are fighting to reform the system. But in the meantime, millions of day laborers continue to be subjected to poverty wages and dangerous working conditions.

Consider the case of Albert Hardy, a 19-year-old from Decatur, Georgia. Last winter, Industrial Labor Service sent Hardy out to work in a local metal yard. The razor-sharp metal sheeting he handled made working conditions dangerous, but the labor pool equipped him only with a thin pair of cotton gloves.

While Hardy worked, a piece of metal ripped through the gloves, slicing his hand and sending him to the hospital to receive stitches.

Later that week, Hardy recalls, he returned to Industrial Labor to pick up his paycheck — which was supposed to include compensation for the two days he was unable to work. Instead, the manager on duty paid him only for the day he was hurt. When Hardy looked at the check, he received an even bigger surprise:

The labor pool had charged him $3 for failing to return the bloodied gloves.

Tags

Adam Feuerstein

Adam Feuerstein, a former reporter with the Atlanta Business Chronicle, is spokesman for the Task Force for the Homeless in Atlanta. (1993)