This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 3, "Sunbelt Blues." Find more from that issue here.

Stinginess as the old saying goes, can be an expensive habit. Just ask Mike Antrican, superintendent of schools in Hancock County, Tennessee. A tight-fisted fixation on keeping taxes low nearly closed schools in his district, the poorest in the state.

“Because of budget cutting, we’ve had to lay off four teachers, several custodians, a Chapter I supervisor, and an attendance and training supervisor,” Antrican says. “We have absolutely no art classes, no music classes. We have no band. If a subject isn’t required by state law, we probably don’t have the money to teach it.”

Last year Hancock County suffered a budget crisis so severe that officials even considered mortgaging school buses to keep the schools open through the end of the year. The state vetoed that idea, and for a while it looked like summer might come early for children in Hancock County.

The school crisis was averted—narrowly—when the county state after state, citizens are forming broad-based coalitions to cut an unusual deal with local officials in Washington, D.C. The District of Columbia shipped 93 convicts to the Hancock County jail—and paid the county $4,185 a day to hold them.

Antrican concedes that some people found it insulting to pay for schools by importing out-of-state criminals. But he points out that the county would have to double property taxes to raise as much money as the prison deal brought in—“and that’s only for the school system,” he adds.

Such stories have become all-too-familiar around the South in recent years, as local and state governments struggle to pay for the schools, sewers, and clinics they so desperately need. Some states in other regions have faced this fiscal crisis and dealt with it. But Southern states, in their eagerness to attract business investment, have habitually kept taxes low—especially for corporations and the rich—making it tough to pay for basic human services like education and health care.

As the region enters a new decade, however, there are signs that the Southern tradition of stinginess is starting to change. In state after state, citizens are forming broad-based coalitions to press for sweeping tax reforms. Teachers, state employees, and even some business leaders have come together to fight for a fair tax system. The bottom line, they insist, is ensuring that taxes spread wealth throughout society rather than concentrating it in the hands of a few.

“When the politician says ‘we will not raise your taxes,’ we

think people ought to understand that the politician is really saying that he thinks we should stay at the bottom of the nation in education, health care, and other human services,” says Robert Guillbeaux, a member of a tax-reform coalition called Alabama Arise. “This state will never achieve its potential as long as significant numbers of its population are poor.”

A Smart Investment

The South can boast of the most inequitable tax systems in the United States. The long domination of state government by large landholders and business interests has led to a reliance on sales and property taxes that fall hardest on families with low and middle incomes. Put simply, Southern states generally raise most of their money by taxing food, clothing, and homes—not land, business profits, and personal incomes. (See sidebar, below.)

In the coming year, most Southern states are expected to spend more—and tax more—than ever before. According to a recent survey by the National Governors Association, proposed spending growth for 1991 in the South “is the second highest in the country and well above the national average.” Steven Gold, author of State Tax Relief for the Poor, predicts that 1991 will also be “a very big year for state tax increases—one of the biggest years ever.”

According to Gold and other analysts, several factors explain the renewed push for state spending:

A lagging economy—some call it a recession — has busted rosy projections of higher tax revenues. Since most states must balance their budgets each year, the loss of anticipated income requires legislators to either cut expenses or raise taxes—choices they hate to make.

Government costs have climbed steadily in the last decade, especially for prisons and health care. The number of inmates in state prisons doubled during the 1980s, while state Medicaid expenses soared 14 percent in the past year alone.

The federal government is rapidly cutting support for state and local governments. Last summer, the Bush governments. Last summer, the Bush administration mapped out a plan to limit state and local income tax deductions—a move that would make it even harder for big cities to provide basic services for the urban poor.

Education reformers are winning lawsuits that force states to divide up school funds equally and stop short changing public schools in poor counties. After losing such suits last year, Texas and Kentucky took prompt action to bolster their budgets. Legislators in other Southern states took note.

“It used to be that when we brought up the poverty of some of the school systems here, most of the legislators would brush it off and say ‘it’s a local problem’ or something like that,” says Bill Emerson, superintendent of schools in Crockett County, Tennessee. “Since the Kentucky case, we’ve seen a whole change in attitude among the legislators. The legislative leaders will sit down and talk with us seriously now.”

The push for more money to pay the bills has fueled the growing support for fair taxes. For years, unions representing public school teachers and state employees provided most of the organizational support for tax reform campaigns. But in the last few years, a broad assortment of groups has campaigned for tax reform legislation. Even business leaders, historically reluctant to support the public sector, seem to be getting the message that social spending is a smart investment, not just an act of compassion.

“It used to be that businessmen thought that all you needed for success were low taxes and a small government,” says Steven Gold. “But more and more, it’s recognized that you need an educated workforce and a good transportation system.”

Even in conservative states like Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee, business leaders have recently taken stands in favor of bigger state budgets. Increasingly, they throw their support behind revenue packages that involve higher taxes for everyone—including the private sector.

“The issue is not high taxes or low taxes, but adequate spending,” says Bob Schwepke of the Corporation for Enterprise Development, a non-profit consulting firm. “If business wants to compete, they’ll need to invest more in education and other building blocks. Otherwise, they’ll have to compete with Third-World countries on the basis of low wages—and they just can’t win that way.”

Such attitudes indicate that the coming year could offer new answers to some old political questions. How much will we invest in our environment, our health, our children? And how do we propose to pay the bills? In three Southern states—Louisiana, Alabama, and Texas—citizens have placed the issue of tax reform at the top of their agenda.

Bayou Tax Breaks

Many people object to tax breaks for large out-of-state corporations—but Zack Nauth puts them to good use. As director of the Louisiana Citizens for Tax Justice (LCTJ), Nauth finds tax loopholes valuable for teaching voters how their tax code lets them down, and why.

“We don’t have any trouble convincing people that tax breaks are bad,” says Nauth. “They know this intuitively. They know their children aren’t getting educated, that their schools don’t have money for decent facilities. But they don’t know where money could come from. They don’t know the extent of their dollars which go back to these companies. They take a look around and pretty much see they’re getting screwed, but they don’t know how or why. We show them.”

According to Nauth, tax giveaways cost the Bayou State more than $300 million every year, thanks to the generosity of the state Board of Commerce and Industry. The Board approves almost every tax break proposed, insisting that the concessions will stimulate economic growth and promote jobs. Between 1982 and 1984, for example, the board approved tax breaks for hundreds of companies—rejecting only one application.

To fight such flagrant abuses of the state tax code, LCTJ worked to build a diverse movement of labor, environmental, and public interest groups. Starting with a narrow base of support, Nauth and others worked to align their goals with the agendas of other progressive organizations.

Last year LCTJ campaigned hard for a bill to strip a 10-year tax exemption from corporations that pollute the environment. About 80 percent of the exemptions go to the petrochemical and paper industries, two notoriously “dirty” industries. To fight the tax break, LCTJ recruited allies not typically associated with tax reform issues, including the Sierra Club, the Louisiana Wildlife Federation, and the Louisiana Environmental Action Network.

It proved to be a dirty fight. Lobbyists for the Louisiana Chemical Association bitterly attacked the bill, insisting that it would scare off potential out-of-state investors. After exhaustive lobbying by both sides, the bill was defeated.

The tax coalition tried a different approach. LCTJ asked the Board of Commerce and Industry to draft a new rule that would deny tax breaks to big polluters. When the Board dragged its heels, the coalition pointed to the record of Citgo Petroleum Corporation.

Citgo, one of the biggest petrochemical companies in the state, had been fined $5,000 by the state on April 6 for dumping toxic chemicals into a Lake Charles bayou. Less than two weeks later, on April 20, the company asked the commerce board for $1.1 million in tax exemptions to expand its Lake Charles refinery. On its application, Citgo swore it was not “under citation for pollution violation.”

When the Board was confronted with the evidence on August 22, one member explained that CitCon Oil—not Citgo—had polluted the bayou. The Board then voted unanimously to approve the application and give Citgo its tax break.

The board smoothly overlooked one point: Citgo owns CitCon.

Furious at the transparent ploy, Governor Buddy Roemer rejected the exemption—and took matters a step further. He ordered all pending tax applications—over $30 million in tax breaks—frozen until the Board drafted the environmental rule LCTJ sought. Members of the coalition were elated by the victory.

“They asked for it by being so obstinate,” says Bob Kuehn of the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, a key member of LCTJ. ‘The industry could have allowed a weak rule to go through, but they fought and fought and fought, and now they’ve been cut out of the process.”

But the coalition is not resting easy. To counter expected opposition from the business community, Nauth and his allies are preparing statistics to show that “dirty” corporations cost Louisiana more in pollution cleanup than they return in jobs.

“We’re going to give them figures that show the thing is an outrageous giveaway and prove that the entire system needs to be reformed,” says Nauth.

Taxing the Trees

While Louisiana fights the power of out-of-state chemical companies, Alabama citizens struggle with their own bully—the timber industry.

For years, Alabama has kept property taxes low to please big timber companies and other large landowners. Forests and farms cover 85 percent of the state, yet they account for only 17 percent of all state taxes.

Three years ago, a small group of citizens decided it was time timber firms paid their fair share of the tax bill. They formed Alabama Arise—a coalition of 57 groups committed to trimming overgrown timber subsidies and improving services for the poor.

No one here expects any dramatic turnarounds of the sort that happened in Louisiana. Members talk instead of the dull necessities of a long-term campaign—pamphlets, conferences, studies, voter outreach programs—the kind of activism that is unlikely to make the six o’clock news.

Carol Gundlach, a member of the coalition, admits that cutting the timber barons down to size won’t be an easy job. “If we get something in the legislature, we can expect a massive campaign of TV, radio, and print ads paid for by the timber corporations and funneled through some ad hoc front group called the ‘Committee for Fair Taxation’ or something like that,” she says. “That’s what they do whenever rural counties try to raise their taxes to pay for education.”

Alabama Arise must also contend with the problems caused by “earmarking” taxes for specific programs. Because polls show that voters oppose taxes in general, but support taxes for specific items like better schools or improved health care, many Southern states have been forced to specify where new tax dollars will go. The Alabama state constitution may well be the most rigid in the nation, mandating earmarking for almost all finances. As a result, 89 cents of every state tax dollar is pledged to specific programs —more than four times the average in other states.

Earmarked funds reassure voters of how their money will be spent—but it also creates problems of its own. According to are port by the Alabama League of Women Voters, earmarking straps services less popular with taxpayers and prevents the legislature from shifting priorities or responding to changes in state needs.

All the same, polls show that Alabama voters want to spend more money to improve their state. According to a survey by Keith Ward, an Auburn University professor, 71 percent of Alabamians would back a tax increase to improve public schools. More than half also favored increases for higher education, mental health, economic development, and environmental protection.

Even the influential business community has grown disgusted with the status quo. “The business community minus the timber industry is in the same place we are,” insists Gundlach. “They know economic development requires an adequate infrastructure and an educated populace.”

At the heart of the struggle, though, is a push for tax fairness. In the long run, that means shifting away from sales taxes and relying more heavily on income and property taxes to ensure that the wealthy pay their fair share.

“We’re not hearing legislators talk about sales taxes anymore,” says Gundlach. “In some counties, sales taxes are up to 10 percent. They realize we can’t go much further in that direction.”

Robert Guillbeaux, another Arise member, says he expects a long, slow struggle to build “a great uprising at the grassroots level.” And what will keep the coalition going until then? “We have no choice,” Guillbeaux says. “We live here.”

Lone Star Struggle

Texas has long resisted pressure to adopt a state income tax—one of the best ways to ensure that people contribute taxes based on their ability to pay—and the current campaign for governor is no exception.

Both candidates fervently oppose the creation of an income tax. The Republican contender, Clayton Williams, even makes a point of swearing to veto any income tax that gets to his desk.

Eduardo Diaz, for one, does not believe them. An organizer for the Texas Service Employees Union, Diaz believes Texans will see an income tax within four years.

“The state will be carrying a debt,” Diaz notes. “Our human services budget will be running a $273 million deficit, and the state constitution mandates a balanced budget. We cannot end the year with a deficit. People are sick and tired of the current situation.”

Texans have every right to be sick and tired. For years, their state government relied on oil taxes to fund almost every expenditure. When oil prices crashed in the early eighties, the state budget crashed just as hard. Since then, Texas has leaned more and more heavily on its regressive sales tax, collecting money from the people who are least able to pay.

Today the Lone Star State boasts the third highest sales tax in the nation, yet it ranks next to last in per capita spending on human services. The state government faces one court order to reform inequities in public school spending, and another to relieve overcrowding in state prisons. Under the circumstances, a state income tax might seem the most sensible solution. But in Texas, the sensible solution has remained unthinkable for decades, even in the midst of past fiscal crises.

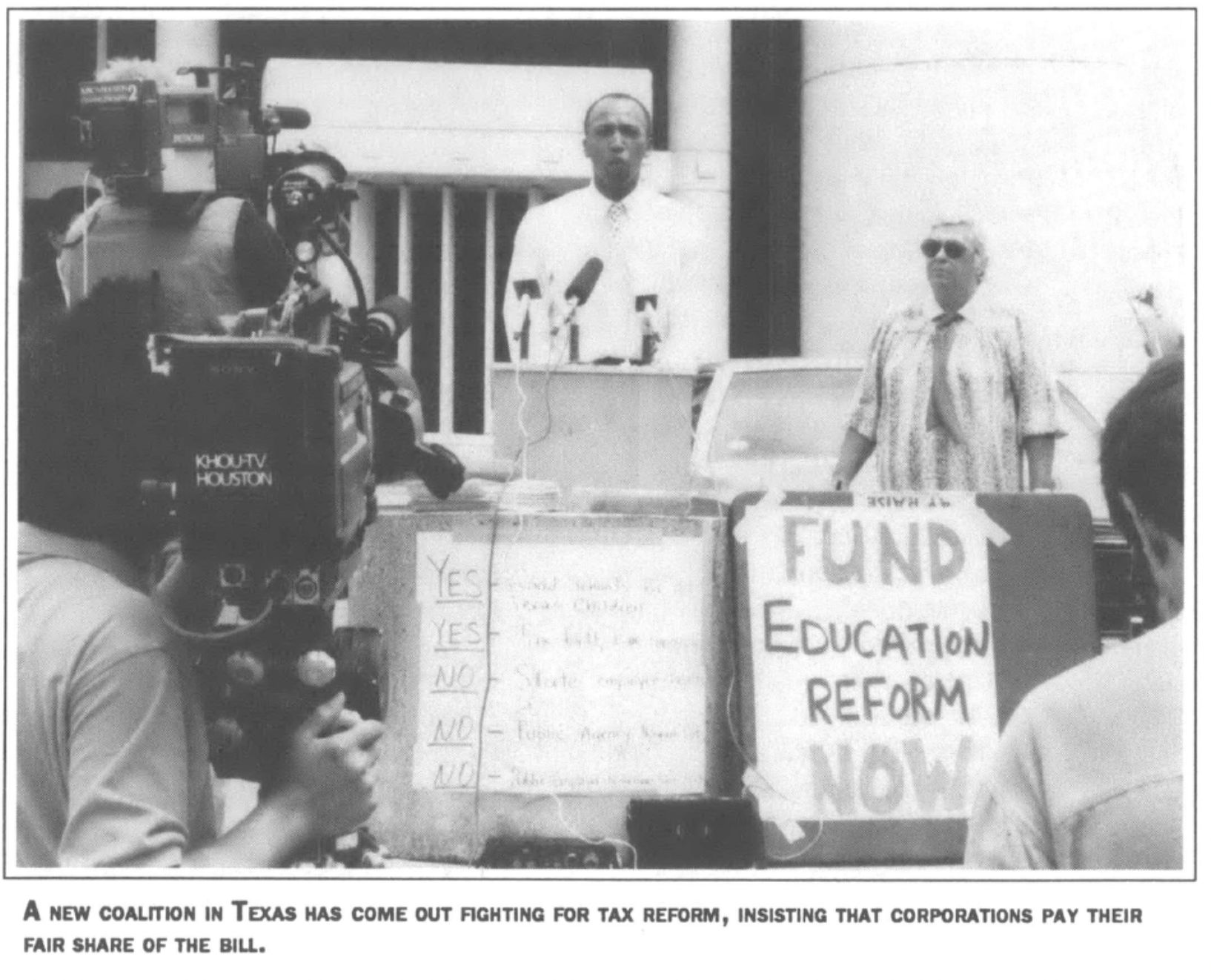

Eduardo Diaz is too modest to suggest another factor that may help win a public blessing for the long-shunned state income tax: the Fair Taxes for Texas Coalition, a campaign his union helped launch with an astonishing alliance of progressive groups that spans the spectrum of race, class, and political agenda.

Jude Filler, director of the Texas Alliance for Human Needs, recalls what drove her network of 112 groups to join the tax reform coalition. “We realized our ‘housing’ members were competing with our ‘hunger’ members, who were competing with our ‘consumer’ members,” she says. “Everyone in our coalition was fighting with everyone else for the same small pool of money. So we decided to make increasing the pool our big campaign.”

The Fair Taxes for Texas Coalition plans to avoid the fall campaigns and focus instead on organizing their members, educating the public, and lining up business and legislative backers. The coalition has already won the public support of Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby and a number of business leaders frustrated by the state’s antiquated revenue system.

Will anything actually change, though? Pessimists say no—but Diaz has heard such defeatism before. “When we started out in 1984, everybody told us we were crazy,” says Diaz. “But all the problems with the budget have changed everything. Once we legitimize the issue and bring it out in the open, we can win this thing.”

A Taxing Dilemma

Although organizers like Diaz remain confident of victory, the growing money crunch in many Southern states threatens to undercut the push for fair taxes. Many reformers find themselves in a painful dilemma: whether to press for income taxes and other progressive plans which might fail at the polls, or to endorse new sales taxes that will likely win approval in the legislature while heaping new burdens on low-income families.

Governor Richard Riley did not want to raise the sales tax in South Carolina. When he first proposed an education reform package in 1983, he avoided a sales tax, blowing that the poor were already paying twice as much of their incomes in taxes as the wealthy.

Instead, Riley anchored his reform to a more progressive plan that would shift more of the tax burden to the wealthy. The plan flopped: Business interests dug in their heels, and voters said it was too complicated. When Riley proposed a penny hike in the sales tax the following year, the education package passed easily.

The governor’s experience in South Carolina set the tone for other Southern states that passed tax increases in the last decade. Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, and North Carolina funded their education reforms with penny hikes. Virginia opted for a half-cent increase, coupled with a 2.5-cent gas tax. Most recently, Georgia extended its sales tax to include food and drugs.

Steven Gold, a frequent advisor to tax reform commissions, understands the dilemma. He advises reformers to campaign for whatever taxes voters will support—not fair taxes that will go down in defeat. “Are you going to fight a two-front war?” Gold often asks organizers. “It can be hard enough to get a big tax increase passed, without insisting that it be an income tax.”

Many organizers have reluctantly agreed, opting for more money over fair taxes. Bill Emerson, who has been fighting for new school funds in Tennessee, supports a state income tax with a higher rate for wealthy taxpayers—but he admits educators will settle for more money any way they can get it. “If the legislature comes up with a revenue package, we will support it,” Emerson says. “Our position is so desperate, we will support any conceivable package. Even if the package includes a lottery, which I personally oppose, our group’s position is to support it.”

No one questions that the economic prosperity of the South in the next century depends on revenue to support its expanding needs. But the question still remains: Will the schools, water systems, and health clinics that the region so desperately needs be carved from the budgets of poor and middle-class families?

To those working to reform Southern taxes, the answer lies with the poor and middle class themselves. Zack Nauth, the Louisiana activist, stresses that only education can prevent unfair taxes. “Our lack of education has been used against us in the distribution of resources,” Nauth says. “You certainly can’t do anything if you don’t know what’s going on. What you don’t know will hurt you.”

Tags

Tom Hilliard

Tom Hilliard is a research associate for Public Citizen's Congress Watch, an organization founded by Ralph Nader. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of Public Citizen. (1990)