This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 3, "Sunbelt Blues." Find more from that issue here.

In 1976, Southern Exposure put together a special double issue on labor entitled, “Here Come a Wind.” Back then the region was in the midst of a manufacturing boom. Factories were flocking south in search of a warmer industrial climate, one where wages are low and union membership is even lower. In the North, they called this migration “runaway shops.” In the South, it was economic development.

Our introduction to that special issue recognized that we were witnessing a dramatic shift of capital, jobs, and people to the South, and wondered aloud what the changing conditions would mean for Southern workers: “Will the runaway shops and homegrown factories offer the same job protection and income enjoyed by their Northern counterparts? Will unions really make a difference? What will be the relationship between identity in community and identity as an employee? What sense of personal worth and individual pride can workers expect from their labor?”

That was nearly 15 years ago, but in many ways it seems like a lifetime. In the span of a single generation, we have experienced nothing short of a wholesale transformation of the Southern economy. Mills have given way to malls; factories have been replaced by fast food. In 1969, one out of every four Southerners worked in manufacturing. Today one out of two works in services or trade, the Burger Kings and K-Marts that consume the landscape.

What is going on here? How did we go from being a land of farmers and miners and furniture makers to a region of waitresses and bank tellers and secretaries?

Even during the boom days, there were plenty of warning signs. After all, a shift of capital and jobs only lasts as long as the captains of capital deem it profitable. If runaway shops could flee the Rustbelt, some suggested, what would stop them from abandoning the Sunbelt? If it can happen to us, Northern workers warned, it can happen to you.

It did happen—not just in the South, but around the world. Workers everywhere are feeling the effects of a global economic squeeze as corporations, knowing no boundaries, move their operations at will in search of ever-lower wages. Instead of enjoying the fruits of their labor, people today work longer hours for less pay, moonlight, take temporary jobs, put their kids to work, do whatever it takes to get by. They also perform more dangerous work: The rate of occupational illness and injury has risen steadily during the past decade.

This is not the result of a recession; there are plenty of jobs to go around. It is a question of priorities, of where the jobs are going. U.S. corporations just went through one of the most lucrative decades in their history. They chalked up record profits, paid their top executives unheard of sums, and had so much cash lying around that they literally didn’t know what to do with it, they just started merging and leveraging and buying each other up and taking each other over.

But the staggering profits weren’t enough, and many companies were prepared to do anything they could to squeeze a few more dollars out of their workers. Some, like the Schlage Lock plant in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, packed up and moved to Mexico, where they could pay workers 72 cents an hour just a few miles from the U.S. border.

Others followed the example of the Tennessee Valley Authority, which laid off almost 40 percent of its workforce while paying “independent contractors” more than a billion dollars to pick up the slack.

Still others, like the Atlanta Journal and Constitution, have used “temporary” workers for years on end. They pay homeless men a few dollars a day, one day at a time, instead of hiring them on a permanent basis and giving them a chance to make a decent living for themselves.

Nowhere is the discrepancy between expanding capital and shrinking labor more evident than in the coalfields of West Virginia. Coal companies have laid off more than 30,000 miners in the state since 1981. Many families have been forced to pack up and move in search of work, and those who remain behind have the second-lowest per capita income in the nation. Yet coal production actually increased during the decade: Last year coal companies dug up 32 million more tons of ore than they did in 1981, the biggest haul in 20 years.

If the economic climate seems gloomy, the forecast for labor is not without its bright spots. Labor unions have made some significant inroads in recent years, winning almost half of all elections held at Southern plants. In many of the more publicized labor battles—at Nissan Motors in Tennessee and Pittston Coal in southwest Virginia—workers have put aside their fears to fight for decent health care and safe working conditions and a say in the workplace decisions that affect their lives.

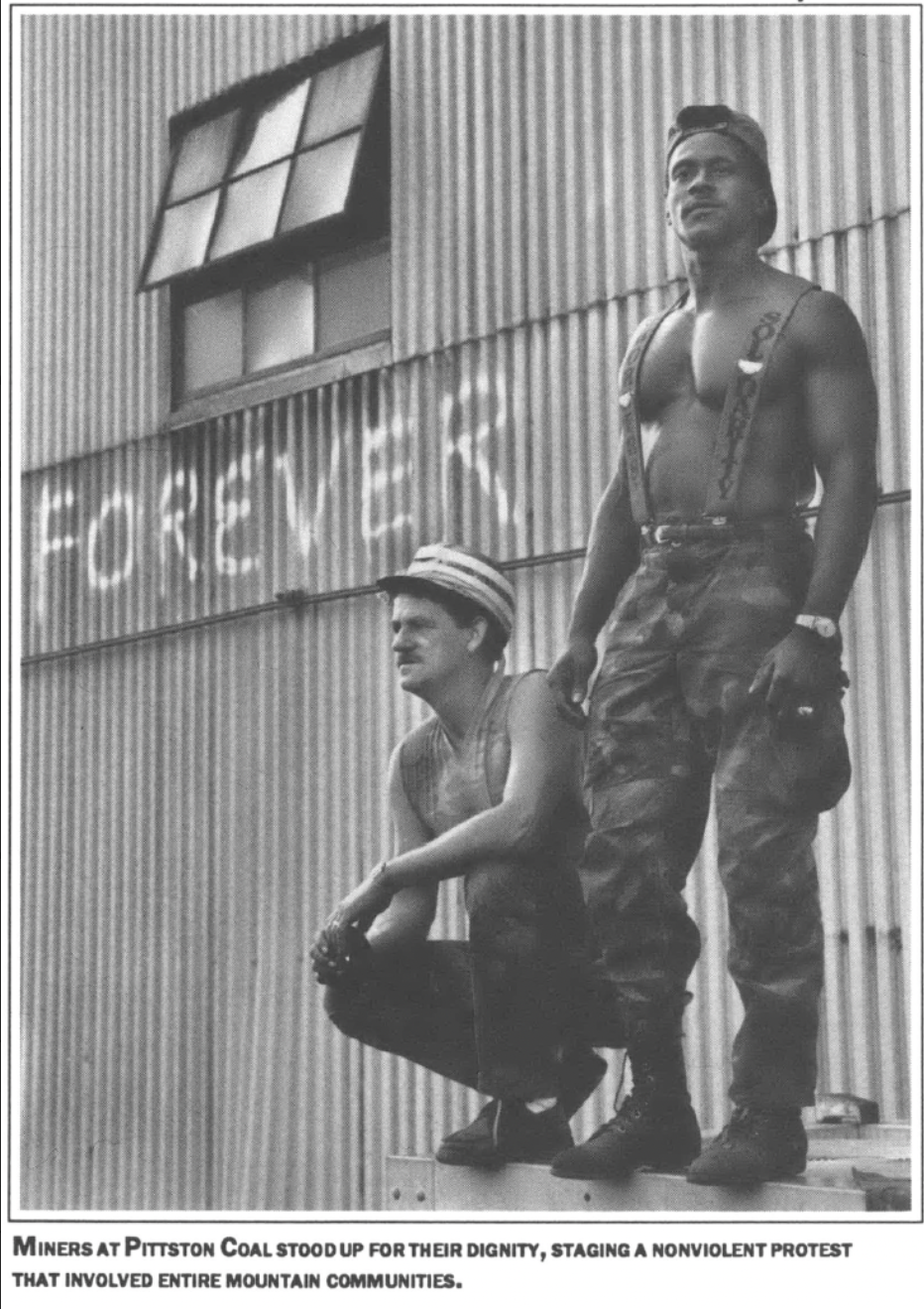

It seems fitting that nowhere is this struggle for personal dignity and social democracy more evident than in the coalfields of Appalachia, where the exodus of capital and jobs has hit hardest. Last year more than 2,000 miners at Pittston Coal walked off the job and withheld their labor for nine long months — not to demand higher wages for themselves, but to prevent the company from cutting off health care benefits for retired miners. They stood up for their families, for their fathers and grandfathers who had worked in the mines. They staged a sustained, nonviolent protest that involved entire mountain communities, and they won.

Such determination demonstrates that Southern workers can respond to changing conditions in the workplace, to the latest movements of capital and jobs. In our special issue on labor back in 1976, we quoted the words of Hobart Grills, who took part in the bloody struggle to organize coal miners in Harlan County, Kentucky during the Great Depression. ‘The coal operators would think they got the union crushed,” Grills observed, “but just like putting out a fire, you can go and stomp on it and leave a few sparks and here come a wind and it’s going to spread again.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.

Nancy Peckenham

Nancy Peckenham is a writer for Cable News Network in Atlanta and former Southern communications director for the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union. (1990)