This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 3, "Sunbelt Blues." Find more from that issue here.

My soul is a hawk

I am but returned from the place the

Indians call

'Land Where The Wind Is Born”

Into the quiet and lonely spaces of the

upper skies soar I

The beauty of Florida below me

As thermal air currents send their

song thru my wing-feathers

And I float in ever-widening circles

Yellow-eyes piercing in rapture

The blues and golds the orange and

faint-pinks of sunset

And I see in the far-far distance my

Have

The majestic old-dead tree

On whose limbs Ifind...

My soul is a hawk.

— Will McLean

Gore’s Landing, Fla. — They threw all that was left of Will McLean into the swift black waters of the Oklawhaha a few months ago. Bleach-white ash and scrapes of bone that once were the man mixed with the minnows and a pouring of wine, swirling away o’ee through the cypress knees on the river edge, vanishing with the falling sun and the bluebird’s final call. A small gathering of friends stood locked in teary-eyed reminiscence until the stars began to twinkle, the mosquitos commenced to feast, and all were holy certain the soul of the man had soared.

The hawk did not appear, but stood and watched from afar, I imagine. Though we looked for those piercing yellow eyes and strained between songs to hear the redtail’s call, only the faint symphony of the swamp bugs emerged. “Amazing Grace” sweetly sounded a finale on Will and the mourners departed, leaving flowers, the old man’s cloth hat, the last of his no-filter Camels, and a flickering candle to the elements of the Florida sand he loved so well.

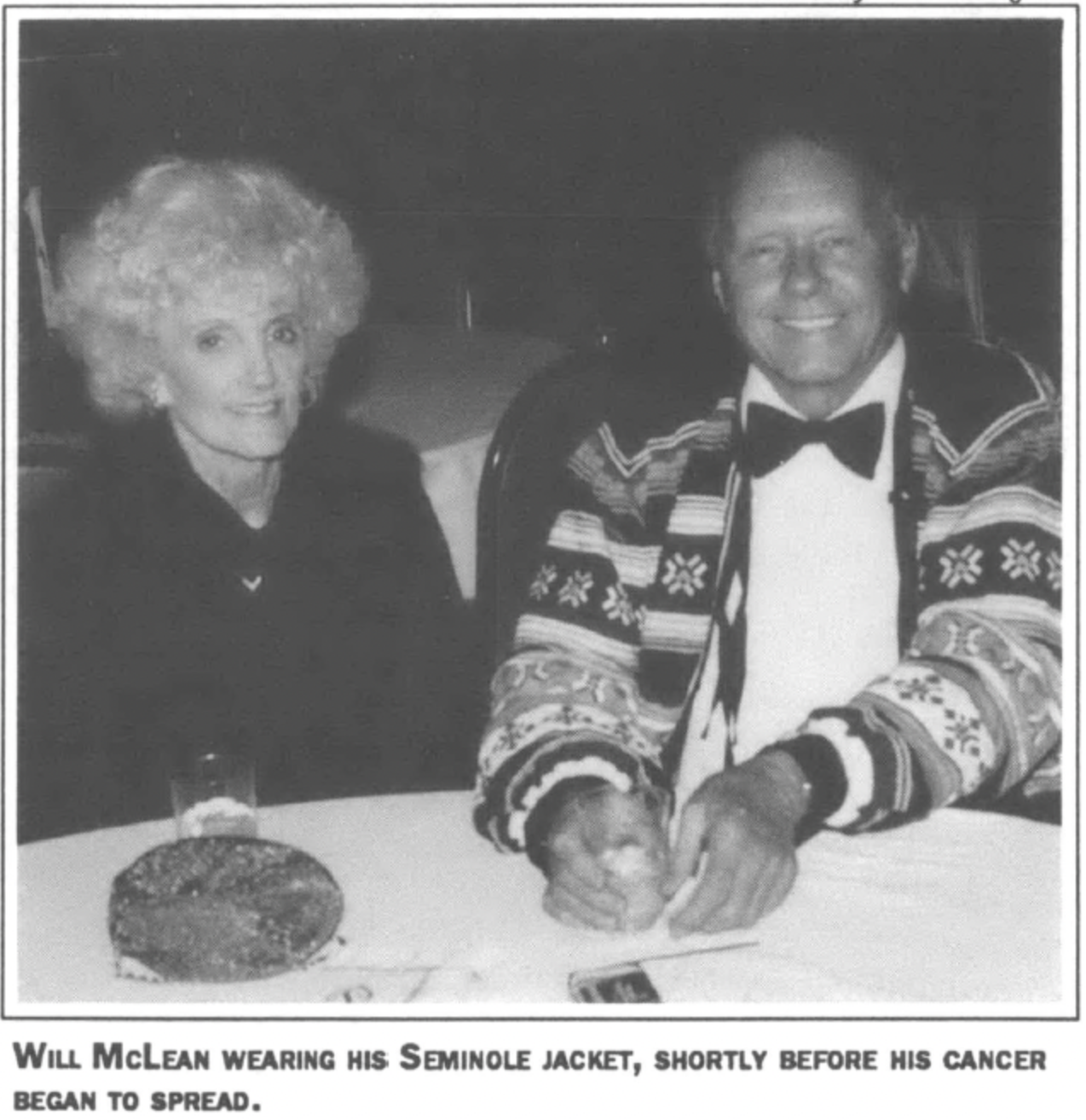

Will had finally died, for good, a few days before. Cancer, damned, deadly cancer took his hair and shriveled him up before it closed those blue eyes for good. A lifetime of smoking and drinking and worrying to excess must have added to all the misery somewhere. Suspicious of fortune be it good or bad, intensely self-destructive, artfully insecure, a giant of a songwriter, a Southern gentleman, venomous lover of a Florida vanishing all around him, Will McLean was that old oak tree in the last forest, the Big Bad John of real Florida music.

Oh listen, good people

A story I’ll tell

Of a great swamp in Florida,

A place called Tate’s Hell.

One hundred and forty

Square watery miles

With millions of 'skeeters

And big yellow flies

And where all about

The moccasins lie,

With glittering death

In their beady eye

Where bull-gators beller

And panthers squall.

Now this is a place

To be shunned by all!

Though he suffered his devils and died his deaths in front of all to see, it is true, as St. Augustine song smith Gamble Rogers said in his eloquent eulogy, “It is we who should have been humbled.” Arguably, Will McLean may be the greatest writer of folk songs that Florida has ever produced.

As the “Black Hat Troubador,” he roamed the backroads of this state for half a century, chronicling in word and music the evasive past and present most of us can only imagine. In the1950s and ‘60s, especially, every great folk singer — from Pete Seeger to Phil Ochs — kept Will McLean tunes and fables in their repertoire. Tough to handle, a purist against commercialism, cracker to the bone, he never cashed in on his creations. Carnegie Hall knew the songs but not the man.

Few have taken guitar to hand and as poignantly portrayed Florida’s real history. It was one of Will’s specialties and he did it like he did all his work: not by reading what some Yankee wrote in some censored history book, but by entering the aura of the Indians, by getting lost for days in the impenetrable swamp, by respecting the old ways, gutting the wild boar and hanging it to bleed, talking to those who were there (or who knew who was there).

He made the Seminole Indians a particular specialty, writing such great historical musicals as “Seminole” and “Osceola’s Last Words.”

In the latter he describes, in a single verse, the pride of the legendary warrior Osceola, imprisoned in a St. Augustine dungeon. Fatally insulted at his capture under a flag of truce, he refused to dignify the enemy by escaping. Instead, the weary Osceola realized his death would best serve the cause. He sent his brother, Chief Wildcat, with these instructions ... says Will McLean.

Wildcat, brother, to the grassy waters

take the Seminole.

There no white man can invade to

leave you lying dead and cold.

I shall not live among such evil men,

who mock the sign of truce,

This flag of white,

And honor not their given, sacred

word

My name will be the light.

Hog Slobber

“How do you know Will is really dead?” Seminole chairman James Billie asked, by phone, when I finally tracked him down with the bad news.

“Well, my friend Sandra left a message with my daughter ...”

“That’s not good enough,” said the chief. “I don’t know whether we should believe it.”

“I saw the obituary in the Tampa Tribune,” I replied.

“You got it right there?” he asked. I said yes. I could tell he was stunned: “OK, I guess it’s true this time.”

Every Thanksgiving, for the past several years, a great depression would overtake Will and he would call the Seminole chief to say goodbye. Each year, at the Florida Folk Festival in White Springs, Will would surround himself with friends to sing some campground dirge, such as “I Will Walk That Lonesome Valley.” We would drink beer and wait for Will to drop right before our eyes, straining to hear the last growls of his deep, resonant voice. His friends kept him alive, hooked to the respirator of love and respect.

Will cringed, however, the last time I saw him, while a high-voiced female folk singer crooned one of his songs nearby.

“You’re supposed to sound like a hog to sing that song,” he complained. “She sounds like a whippoorwill.”

In all the articles and reports documenting the great storm and flood that wiped out the world south of Lake Okeechobee in 1928, only Will’s eyes put the horror into that universal place where all could feel the chill: “When the waters receded, great God what a sight,” Will wrote. “Men, women and children returned black as the night.”

Where pantywaist Steven Foster looked for names to rhyme, Will McLean stared the wild hog in the face and told us about that “slobber running down his jaw.”

We could go on and on through the lush catalogue of his work and marvel at such observations and peer between the lines and come up with all those wisdoms the scholars manage to drain out of the soul of the departed legend.

Will McLean, during his younger songwriting days, soared about the Florida landscape with the eyes of the hawk he so identified with in the end. Each movement of each blade of grass, the fading scream of the panther, the moaning of the wilderness was emblazoned on his brain and he drank and shook, sweated much of it onto paper and slobbered it out his harmonica so we would have the most precious of treasures the great scribe could afford—preservation of a real world that lived and breathed and ain’t never gonna be put in any history book that kids will be allowed to see.

A State-Fixed Guitar

And that is what is really sad. Although Will McLean left us remarkable treasures, he died a fantastically discontented soul. The state which he had glorified so beautifully had stared him full face with vacant eyes as he drank away the last 20 years of his life. In his last few years, he must have lived in a dozen different dwellings, including a van that burned up and an apartment that burned down. His life was so wrapped up in survival, he was unable to draw out that which makes him a legend in death. Instead of adding to the body of Florida culture, he was often an embarrassment, usually rejecting the well-meaning but godawful token efforts we all made to help him out.

Yes, those in high bureaucratic places gave him the “Oscar”— the prestigious Florida Folk Heritage Award — but it was nothing more than a grandiose gesture from the keepers of Florida’s arts and culture, bitter recompense for the great contributions to that culture by this hard-to-manage, self-destructive, get drunk, love-Florida songwriting man.

It doesn’t have to be this way. In Japan, people like Will McLean are considered “Living Treasures,” and the government takes care of their basic needs. Far advanced from our cultural management scheme, the system which oversees the fortunes of Japanese artists does indeed what we put on plaques. They make sure the basic bills are paid, the artist has a palette, and the art goes on.

The question to consider is this: What value do we place on the works of a Will McLean? Not as much as the Japanese, apparently. We could have cut a few trips off the healthy travel budget of Secretary of State Jim Smith and saved enough money to support Will for a year.

And yes, he might have drunk himself into a stupor or entertained those legend-mooching friends that never seemed to leave. Or, he might have turned on his state-bought tape recorder and, in the misty cool of some November night, sipping on state whiskey, strummed his state-fixed guitar and coughed up something revealing and beautiful about ourselves and this place in which we live and breathe, some thought that leapt from that bursting pressure-cooker of potential he died with, some contribution to the culture that is uniquely Floridian.

And because he would not have been required to do anything, because he would not have been required to show up here or there, file this or that or justify in any way the investment by the state, my guess is he would have done all of that and more. Perhaps we would have had volumes more of Will McLean songs commenting on the incredible change our growing population has wrought on the dwindling wildlands of this fragile peninsula.

Certainly, we have not yet learned our lessons. We know that overdevelopment is choking us, yet we approve new projects every day. I’m so tired of hearing politicians say, ‘Well, we can’t put a fence up on the state line!” Isn’t there a better way to say that? Maybe Will might have conjured up a different vision on some cool night when the devils were asleep and the urge to create was a volcano in his soul. We all know Will had something more to say. The tragedy is, he never had a chance to say it.

Doo-Dads and Mojos

Will was not the last tree in the forest, but the foliage is thinning. There are others just like him, who can still do the thing for which the state will shake their hands and give them medals and brag on them at the next convention when all the bureaucrats gather to compare notes.

Just the other day I went to visit Diamond Teeth Mary McClain, the 88-year-old blues and gospel singer who lives in East Bradenton. Her phone had been cut off, there was nothing in her refrigerator, she had no money, it was a week before her Social Security check would arrive, and she was just sitting there, withdrawn, depressed, on a couch, staring at that Florida Folk Heritage Award on the wall across the room. That award and two bucks couldn’t get her a cab to the nearest convenience store.

Her voice is still strong, her stories are still lucid. Her connection to a time and place most of us don’t know is immense — if only she could get a ride. There are basket weavers, painters and sculptors, storytellers, luthiers and fiddlers gathering dust in the basement of Florida culture.to the gig! Like Will McLean, Mary is a living treasure, but the state rarely calls to check on her. The Florida Folk Arts Program has no “hard times” budget to deal with the real-life problems of living legends. Sure, there are other social agencies charged with caring for certain needs of this woman, but she is more than that — Mary is also a blues singer and a gospel singer and her creativity is so enrapturing that she will work for hours putting together beads and doo-dads into mojos and plant hangers and only God knows what they’re for.

Like Will McLean, there is no category for such people. The budget has no line item for preserving this sort of culture. The process usually doesn’t even click in until they are dead. Legislators who won’t even blink to allocate millions of dollars to ruin my quality of life by making a four-lane into a six-lane in Ft. Lauderdale will put on their reading glasses, huff up their chests, and rail against giving a few bucks to an artist whose family lineage doesn’t flow though the guilded pocketbooks of Palm Beach.

Like Will McLean, Diamond Teeth Mary is a living treasure ... crashed on the reef of old age and sunk beneath the black ocean waters of an ignorant bureaucracy. There are basket weavers, painters and sculptors, storytellers, luthiers and fiddlers gathering dust in the basement of Florida culture. When they are gone and no longer a hassle to deal with, like the great woodcarver Jesse Aaron or the incredible junk sculptor Stanly Papio, their work will be displayed in museums and their glory preserved on typeset notecards behind glass.

Next time the state puffs out its chest and extols the virtues of its culture, take a look behind the stage. There are treasures to be found before they are lost.

When in my final sleep

I trust my soul

Departs into

The heavens deep

For I’ ll have done my best

Away O'ee!

Tags

Peter Gallagher

Peter Gallagher is a writer with the Seminole Tribe in Hollywood, Florida. (1990)