This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 3, "Sunbelt Blues." Find more from that issue here.

The morning of June 6 dawned cloudless and humid. Weather forecasters promised a scorcher, and workers talked about the heat as they filed into the AT&T Nassau metal recycling plant outside Gaston, South Carolina.

Midway through the morning shift, an announcement caught the factory’s 680 workers by surprise. Men and women stood at their stations, tools frozen in their hands, as a disembodied voice on the P.A. system told them they would lose their jobs in 60 days.

“Have you ever been out driving... you see a dark storm cloud come up, and all of a sudden the bottom falls out? That’s what it felt like,” said Al Bouknight, a 12-year employee in the plant’s environmental control division.

AT&T had sold the plant to Southwire, which reportedly plans to reopen it and make cable under contract for AT&T—with a smaller, non-union workforce. Harry Monroe, president of the Communication Workers of America local that represents the Nassau workers, called the shutdown “a union busting move.”

“If the pay’s not good enough to survive on, I may have to leave the area,” said Bouknight, who depended on his $9.06 an hour to support a wife and two children. “It’s no fun being outlooking for a job with a gas shortage and a recession coming up.”

Plant closings, wage cuts, union-busting, subcontracting—the telltale signs of an economy turning hostile to workers—have replaced the glitter of the New South boosterism. The gains Southern workers made during the 1960s and ’70s are fast dimming.

A new set of prevailing economic winds have brought thick clouds over the Sunbelt. The forecast looks bleak—not just across the rural landscape and energy-dependent states like Louisiana and West Virginia, where hard times and double-digit unemployment have become a way of life, but in boom towns like Atlanta and Nashville and the Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C.

The dramatic downturn in the regional economy is part of a larger squeeze that is forcing people to work harder for less pay, diminishing the living standard for U.S. workers. Since the recession of 1981, an economic crunch has rolled from region to region—from the Rustbelt to the Oil Patch, up to New England and down to the Deep South. Unemployment has remained unusually high in many states, union membership is down, and Reaganomics has redistributed wealth from ordinary workers to the super-rich.

Nationally, one in three workers now earns poverty-level wages, an increase from one in four in 1979. Executive pay in America’s largest corporations jumped by 149 percent during the 1980s—an average hike of $ 173,000 after inflation—while hourly workers at the same firms saw the value of their wages drop five percent.

To better understand the changing climate for workers in the region, the Institute for Southern Studies reviewed federal and state employment data for the past 20 years. Our questions were simple: Where do people work? What do they earn? What progress have women and minorities made since the sixties?

Goodbye, Factories

Shackled by its legacy of slavery and destruction from the Civil War, the South lagged behind other regions in economic development. As farm profits declined, New South politicians wrapped development strategies around hopes of attracting labor-intensive manufacturing industries to the region. The advent of air conditioning and the end of Jim Crow segregation brought in hundreds of factories from the North, and later Europe and Japan.

By the end of the booming 1960s, manufacturers employed nearly three out of 10 non-farm workers in the region. Most turned out what we now think of as traditional Southern products—textiles, furniture, processed foods, and apparel. During the 1970s, manufacturing employment increased by another 20 percent.

But the factory job machine ground to a halt in the 1980s, growing by a mere 1.2 percent during the decade. The region as a whole added 6.6 million new jobs—but only 68,500 were in manufacturing. In many states the swing in manufacturing employment resembled a decennial yo-yo: up 36 percent in Texas during the seventies and then down five percent in the eighties, up 12 percent in Tennessee and then down 0.2 percent, up 17 percent in South Carolina and then down two percent.

According to U.S. Labor Department data, the biggest manufacturing losses hit workers in traditional Southern industries:

Textiles. In 1969, the industry employed 15 percent of all nonfarm workers in the Carolinas and eight percent in Georgia. By 1989, its share of the workforce had dropped by more than half in each state and in the region as a whole.

Apparel. Last year, the cut-and-sew business employed 525,500 Southerners, down from 571,800 a decade earlier, trimming its share of the regional workforce by 74 percent.

Tobacco. The “golden leaf” has done a slow burn, with employment shrinking from about 58,000 in 1979 to 44,000 in 1989.

The net result has been a dramatic shift in the composition of the Southern workforce. By last year, less than one worker in five earned a living from manufacturing —a drop of 35 percent from two decades earlier.

Initially lured to the South by cheap labor, factory owners have discovered it can be had even cheaper—try 40 to 65 cents an hour — in Mexico or Taiwan. The corporate merger mania has also left many companies saddled with debt and for ways to cut costs. As a result, the same states that lead the nation in new factories—the Carolinas, Georgia, Tennessee—also lead in plant closures. In the first seven months of this year, 50 textile and apparel plants closed in Georgia and the Carolinas.

Many workers feel betrayed. “When AT&T hired me, they talked like I could retire here,” Bouknight said after learning of the Nassau plant closure. “Now we’re being given a little severance pay and told, ‘So long.’ We’re finding out AT&T don’t have no use for you when they don’t need you anymore. All they care about is the dollar.”

Goodbye, Farms

Manufacturing is not the only sector of the Southern economy undergoing upheaval. Other industries that account for a smaller share of the regional workforce have also suffered during the past two decades:

Farms. The steady decline in Southern farms since World War II has continued apace. Once the region’s pride, the share of regional income earned by farmers dropped by half between 1969 and 1989.

Mining. The proportion of Southerners employed in mining dropped by 29 percent, with catastrophic results in states dependent on coal. In 1979, one in 10 employed West Virginians was a miner. Today the ratio is one in 20, and the state suffers from the highest unemployment rate in the country.

Construction. Despite the much-heralded boom in office towers and real estate developments, construction workers saw their share of the employment pie shrink by 18 percent in the last two decades.

Government. While employment in local and state government has kept pace with the South’s growing workforce, the federal government’s share of the overall pie has shrunk by 31 percent since 1969. At the Tennessee Valley Authority, the largest federal employer in the region, massive layoffs have affected 20,000 employees since 1980 — two fifths of TVA’s workers.

The TVA layoffs underscore a region-wide employment trend: Scores of companies are firing permanent employees and hiring temporary workers and outside contractors. Since 1985 the agency has signed temporary contracts totaling $1.3 billion, and late last year TVA officials revealed plans to increase fees for outside contractors by an additional $152 million.

Dorothy Kincaid was one of the casualties. Last spring the 43-year-old data processor lost her job after 17 years at TVA. She was replaced by a temporary worker who is paid by the hour.

By the time she left, Kincaid had already been forced to work part-time and give up her benefits. “TVA office workers are being handled just like factory workers right now,” she said. “I’m so sad I put so many years into a job that I lost just like that.”

Hello, McDonald’s

Although Southern manufacturing and other industries stagnated or declined during the past decade, they left an enlarged industrial base in their wake. An expanding middle class spawned airports and beltways, stock brokers and strip malls, junk-food restaurants and junk-bond banks. Businesses dealing in services and information increasingly outran those producing hard goods. Kentucky-fried chicken outpaced Kentucky-mined coal, and employment surged in two sectors of the economy:

Services. Three million of the 6.6 million jobs added in the South during the 1980s were in services—hospitals and nursing homes, motels, copy centers, law offices, travel agencies, business consultants, and temporary office pools. The growth was most dramatic in Florida and Virginia, which together accounted for more than a third of the new service jobs.

Wholesale and retail trade. Another two million jobs came from this sector, which includes fast-food restaurants and convenience stores. More than two thirds of the growth came in just four states —Florida, Texas, Georgia, and North Carolina.

Taken together, service and trade far outpaced the rest of the country. Over the past two decades, the number of trade jobs climbed by 115 percent in the South and 63 percent outside the region. Service jobs jumped 194 percent in the South, compared to 126 percent in the rest of the nation.

One service field that saw an explosion in job creation was private health care. Since 1969, employment in the industry has soared 261 percent in Mississippi, 233 percent in Virginia, and 218 percent in Texas. In Kentucky, health care now employs twice as many workers as construction. The job growth continued during the 1980s, as the Reagan administration promoted private ventures in health care.

Another Reagan legacy—a surge in corporate takeovers and real estate speculation —fueled an 18-percent job spurt in the areas of finance, insurance, and real estate. Combined with government work, these paper-shuffling trades now employ 23 percent of Southern workers.

The decline in manufacturing and the growth in services and trade have altered the employment landscape in virtually every Southern state. In Tennessee, for example, government officials like to boast about the arrival of big automakers like Nissan and General Motors. Yet car manufacturers still employ less than half as many Tennesseans as the textile and apparel industries, which account for 87,500 jobs. By contrast, 119,800 Tennesseans work in retail eateries and 145,800 work in hospitals, nursing homes, and other private health care facilities.

What They Earn

Service and trade jobs may have beat out manufacturing as the biggest source of Southern employment, but they can’t compete with the wages and benefits of the region’s old industrial base. Not that factory work in the South ever paid all that well by national standards. Last year the average hourly pay for manufacturing workers in the region ranged from a high of $ 11.36 in Louisiana to a low of $7.98 in Mississippi—the lowest in the nation. Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas are also among the lowest-paying states in the nation for factory work.

Still, the difference between $8 an hour and minimum wage adds up to more than $8,000 a year. Joan Sharpe went 18 months without work after being laid off by the Schlage Lock Plant in Rocky Mount, North Carolina in 1988. She now works part-time at a bank and earns $5.50 an hour.

“I looked at temporary agencies. But they only guarantee you a couple of weeks’ work and then you’re laid off again,” said Sharpe, a 32-year-old black woman who worked at the metal Finishing plant for 10 years before it moved to Mexico.

“I’m not making as much as I was, but at least I do have benefits. Thank goodness I don’t have children to support. That would really be hard,” said Sharpe.

A few sales and service positions pay well, but the vast majority provide just a hair over minimum wage and offer few or no benefits. Surveys indicate that service jobs account for three quarters of all full-time workers who lack health insurance.

Eight months after finishing a retraining course in clerical work, Shirley Martin, a 50-year-old former textile worker, has interviewed for dozens of openings without success. “I think my age works against me. Most employers are looking for younger women with more experience.”

Martin finally took a job as shift manager at a laundromat where she works for minimum wage. “I’ve seen my pay cut in half and I have no benefits. I work four nights a week and 12 hours a day on Sat-

urday and Sunday. I even worked Christmas Eve.”

Tens of thousands of workers have similar stories to tell these days. Fifteen months after massive layoffs by the Allied Signal seat belt factory in Knoxville, Tennessee, the Highlander Center surveyed 170 of those who had lost their jobs. Barely half had found work, and the average wage for those lucky enough to find a job had dropped from $5.76 to $3.70 an hour.

National studies bear out the Highlander findings. A 1986 study prepared for the Joint Economic Committee of Congress revealed that 42 percent of all new jobs in the South in the first half of the decade paid less than $7,000 a year. Another 1986 study by political economists Barry Bluestone and Bennett Harrison showed that the national growth rate for low-wage jobs in the mid-1980s was triple that of the mid-1970s.

A big reason for the spread of low-wage jobs is the creation of what Forbes magazine has dubbed the “disposable” workforce. Today almost one third of all workers hold part-time, temporary, or contract jobs. The Labor Department calculated that hiring so-called “contingent” workers to avoid paying benefits can save companies 15 to 24 cents on every payroll dollar.

Part-time jobs grew twice as fast as full-time positions in the last decade. The South now leads the nation in the number of part-time workers looking for full-time work, with Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee topping the list.

Even those who manage to hold on to full-time production work have suffered a decrease in earning power. After adjustments for inflation, the hourly pay of nonsupervisory production workers last year was only 36 cents more than their earnings in 1969—and 46 cents lower than what they earned in 1979.

Given the shortage of full-time jobs offering adequate pay, it’s not surprising that record numbers of workers are holding down more than one job. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 6.2 percent of all workers moonlight—the highest level in more than 30 years. Nearly half say they must do it to pay their bills.

Pink and Black

The gap in wages between men and women persists, but it has closed somewhat. Last year women earned a median of 72 cents for every dollar men took home, compared with barely 59 cents in 1970. But such figures may indicate not that women are earning more, but rather that men are making less. In their 1986 study, economists Bluestone and Harrison observed that white men were particularly hard hit by the decline in high-wage jobs in the early ’80s. Between 1979 and 1984, an astounding 97 percent of all new jobs filled by white men paid low wages.

For that reason, the researchers cautioned against comparing the progress of women and minorities to the status of white men. “Improvement in these ratios owes more to the fact that white men are suffering losses than that other groups are making great gains,” they reported.

Nevertheless, employment data from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission indicate that Southern blacks and women made substantial job gains in the past two decades. Affirmative action programs have helped double and triple the proportion of blacks and women in managerial and professional jobs.

But the overall numbers are still pitifully small. Black men made up over 10 percent of the Southern workforce in 1988, but they held only five percent of the managerial and professional jobs and almost 17 percent of the blue collar and service jobs. What’s more, the lion’s share of progress took place in the seventies. New job opportunities for women and minorities dried up with the onset of the 1981 recession and the Reagan administration’s campaign against affirmative action. Women in the South—including married women—have always worked outside the home in higher proportions than their non-Southern counterparts.

What’s more, they have always been more likely to hold manufacturing jobs, dominating textile sweatshops and other dangerous and low-paying workplaces.

In the last two decades, the rest of the nation has undergone something of a “Southernization” of the workforce. Women across the country have entered the job market in greater numbers than ever before. Seven out of 10 women aged 25 to 54 now work, up from five out of l0 at the end of the sixties.

In the South, women—white and black—still hold most of the “pink collar” clerical and office jobs, relatively low-paying positions with high numbers of temporary and part-time workers. Clerical jobs have always been seen as “women’s work,” a characterization that’s even more accurate today: fully 85 percent of these jobs now go to women, up from 75 percent in the sixties. Black women account entirely for this increase jumping from three percent of all clerical and office workers in 1969 to 14 percent today.

In the past two decades, women have also taken over the majority of jobs in the low-paying area of sales and service—a job category formerly dominated by men.

Black women also fill 13 percent of all laborer’s jobs—up from seven percent in 1969—replacing black men almost one for one. As a result, Southern blacks still hold more than a third of all jobs as manual laborers, even though they make up just under 20 percent of the region’s nonagricultural workforce.

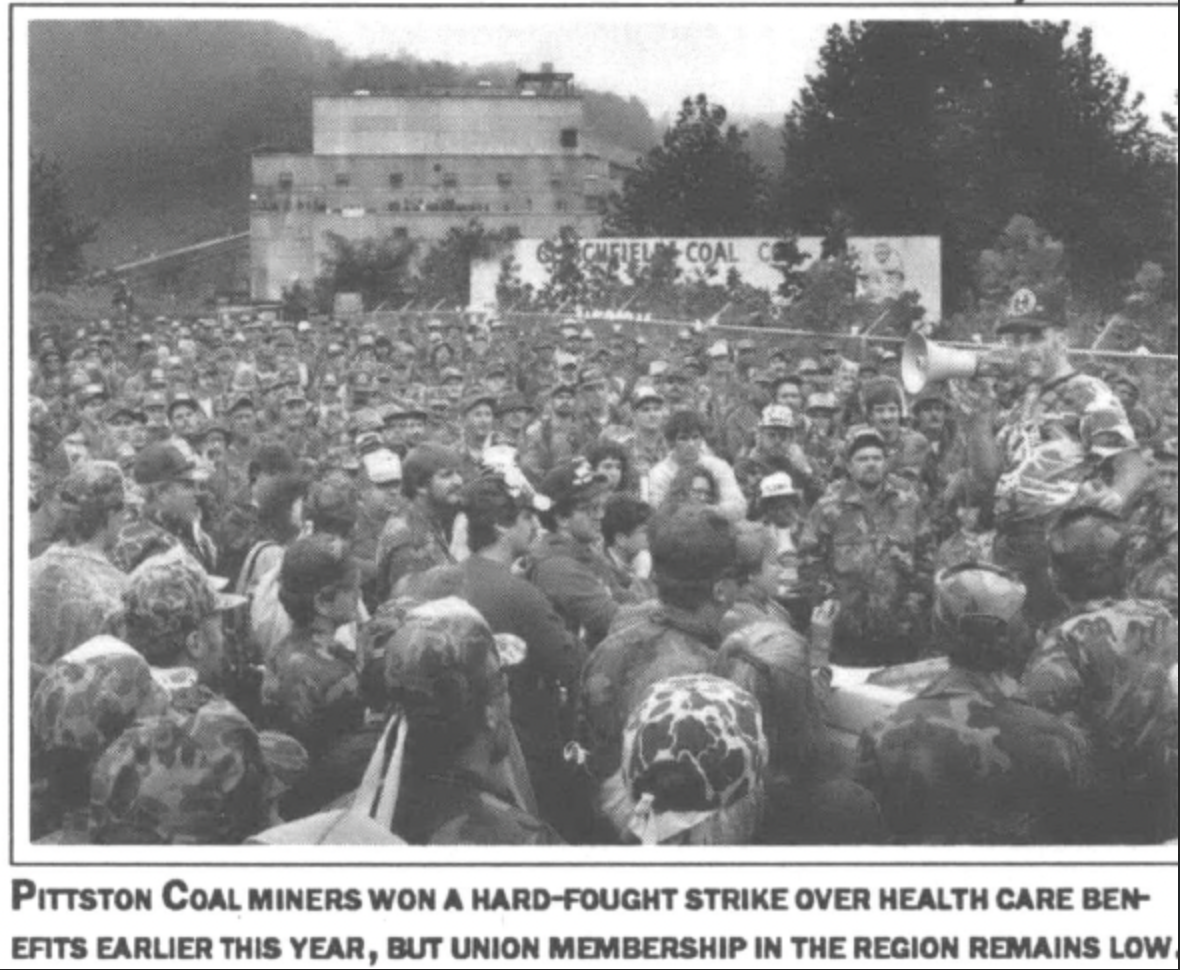

Union Blues

The decline of manufacturing, the deterioration of living standards, the surge of “temp” work, continued job discrimination—where has organized labor been while all this was happening?

For the most part, labor unions have failed to meet the workplace challenges of the 1980s. The fear of job loss stimulated by the 1981 recession and President Reagan’s breaking of the air traffic controllers’ union in 1982 set the tone for the decade. Workers feared for their individual jobs, and corporate America reached a new consensus on using union-busting tactics.

The Government Accounting Office reported that only half as many strikes took place in the eighties as in the previous decade. In the strikes that did occur last year, nearly a third of employers hired permanent replacements—a practice that was rare in the seventies.

The loss in union clout has already been felt in weaker contracts as workers have become accustomed to takebacks, cuts in benefits, and lump-sum payments in lieu of the cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) that were standard in the seventies. In the five-year period following 1981, the percent of U.S. workers under major bargaining agreements with COLA provisions fell from 60 percent to 40 percent.

The South has always been less unionized than other regions and the spread of union-busting tactics, combined with attrition from layoffs and plant closures, has eroded the base of organized labor that exists in the region.

Southern union membership in manufacturing, the most organized industry, shrunk by 12 percent between 1984 and 1988. Today only 14 percent of the region’s production workers belong to unions, compared with 19 percent nationally.

The loss of union representation is likely to have a direct impact on wages in the years ahead. It is no accident that the states with the poorest wages are the ones with the weakest union representation.

Despite company fear tactics, Southern workers continue to organize—and some talk of joining forces with low-paid workers in other countries. “Now companies are paying 80 cents an hour to Mexican women to do the same thing we were doing for $7—and both workforces are underpaid,” said Joan Sharpe, the North Carolina worker who lost her job when the Schlage Lock plant moved to Mexico. “The way I see it, the only way either group of workers is going to get anywhere is to get organized.”

New Skills Needed

Unions have long called on government to provide better job training, and economic analysts and policymakers are slowly coming to the same conclusion. Low wages and tax breaks, they agree, are no longer enough to attract industry to the region. The most important move the South can make to guarantee future jobs is to improve education for workers.

According to a report by the Southern Growth Policies Board, a regional development think tank, “Successful firms—both manufacturing and service—require a scientific and technologically literate work force.” The report also pointed out that counties with the most job growth tend to be those with the most high-school graduates.

Retraining options for older workers must be a priority as well; laid-off workers clearly want to learn new skills, but few can afford the time. Juliet Merrifield surveyed laid-off Levi’s workers in Knoxville, Tennessee. “Many wanted to make a real career change,” she recalled, “but they were told they’d only have 26 weeks of unemployment —not enough to go back to school.”

Harry Monroe, the union president representing workers laid off at the AT&T Nassau plant in South Carolina, doubts that workers will have much to choose from in retraining courses. The state has nearly depleted its federal funds earmarked for job training.

Al Bouknight, one of the laid-off AT&T workers, said he hopes he’ll get the chance. “I been thinking about retraining in something like diesel mechanics or industrial electronics. I don’t want to end up flipping no hamburgers.”

Two years after losing her job at Levi’s, Shirley Marlin speaks for many workers when she recounts the frustration of retraining, only to find herself in a dead-end minimum-wage job.

“I was so sick of factory work I could have gone and blown that factory up,” she said with a laugh. “But if a factory job came open today, I would take it.