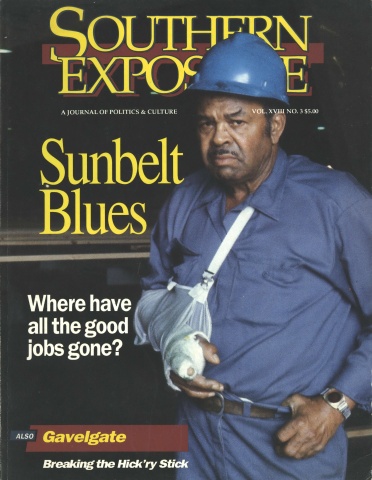

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 3, "Sunbelt Blues." Find more from that issue here.

The way the media portrayed it, you would have thought it spelled the end of organized labor in the South.

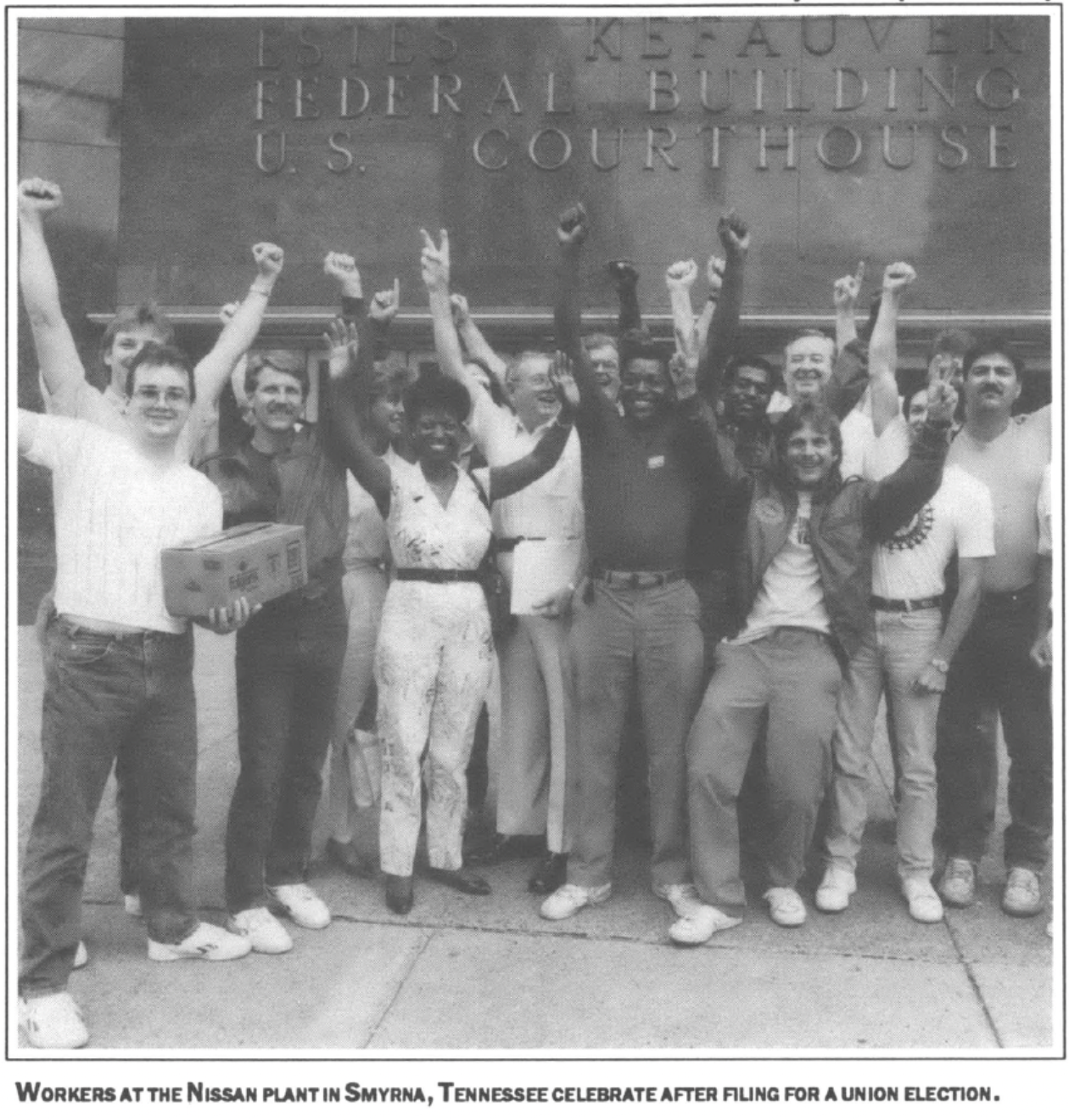

More than 2,300 workers went to the polls at the Nissan Motors plant in Smyrna, Tennessee on July 26, 1989 to vote in a hotly contested union election. At issue: whether workers wanted the United Auto Workers union to represent them in grievances and contract talks.

The Nissan workers held the highest paying jobs for miles around, and the company went to great lengths to turn them against the union. Nissan flew selected workers to Japan for special “training” and used psychological profiles to hire workers who were unlikely to join the union.

When the votes were counted, the union had lost by a margin of 1,622 to 711. It was a disappointing setback—but much of the media hailed it as a stunning defeat. “Nissan Workers in Tennessee Spurn Union’s Bid,” made front-page headlines in The New York Times for July 28.

It was a different story eight months later, when 1,340 workers at the Freightliner truck body plant in Mt. Holly, North Carolina voted to join the UAW. The victory last April got little press attention — even though it was a major organizing victory affecting a large work force in a traditionally non-union area.

Nor was it an isolated win. The Freightliner vote was one of a series of recent union victories that are breaking stereotypes about organized labor in the South. The record of success shows that while the Nissan defeat got the attention, union drives in auto and truck plants around the South are getting the results.

The UAW has not been alone in winning recent elections. The United Rubber Workers and ACTWU are succeeding in organizing in related industries, such as seat covers and tires. In communities across the region, unions are winning in staunch non-union areas despite intense and sophisticated anti-union campaigns:

April 1988— Auto seat cover workers at Gardener Manufacturing Company near Knoxville, Tennessee vote to join the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU).

April 1988—The United Rubber Workers win an election at Firestone Mills in Gastonia, North Carolina. Workers at the tire yarns plant overcome 60 years of union opposition to win 213 to 198.

April 1989—Workers at the Mack Truck body plant in Winnsboro, South Carolina vote 453 to 398 to join the UAW.

January 1990—Irvin Automotive workers in Dandridge, Tennessee vote 123 to 111 to join ACTWU. Fourteen ballots are challenged, but the union prevails.

February 1990—The UAW organizes two small electrical motor suppliers in Hendersonville, Tennessee. The pro-union vote was 133 to 59 at Bosch and 47 to 38 at General Electric.

June 1990—The UAW wins again at Coats, an equipment manufacturer in Lavergne, Tennessee, just minutes down Highway 41 from the Nissan plant. The victory at Coats means an end to a company system that kept workers on “temporary” status for up to four years with half pay and no benefits.

“The first half of 1990 has been the best six months since I came on in 1976,” says Bob Miller, a regional organizing director for the UAW. “We have won 10 out of the past 14 elections on card checks”—sometimes signing up so many workers at a plant that the company agreed to negotiate a contract without holding a union election.

Buck Shot Memories

Other organizers agree that the recent string of successes at smaller plants demonstrates that Nissan is not the norm. “This year will be the UAW’s most successful year since the beginning of the Reagan administration,” says Carlton Homer, UAW national organizing coordinator.

Such optimism comes on the heels of a long, hard decade for labor unions. The last banner year for UAW organizing was 1981, when the union defeated General Motors’ “Southern strategy.” Throughout the late 1970s, GM had tried to take advantage of low wages and anti-union laws by building new Southern plants. The union responded by organizing every GM plant in the region.

In the years that followed, however, the union experienced few victories. Antiunion moves by the Reagan administration came down early and hard on workers’ rights to organize. Faced with tough times, some unions opted for a strategy of “cooperating” with management, giving in to company demands for concessions.

So why the change now?

“Corporations have had it made for the last 10 years and they have taken advantage of workers,” Horner says. “They’re terminating pension plans by the thousands, withholding normally expected pay raises, and changing insurance provisions to discourage workers from using health plans.” “People have been squeezed,” adds Ben Perkins, assistant director of organizing at UAW headquarters in Detroit “Maybe it’s just that they can’t take any more.”

Although workers may be fed up with low pay and company takebacks, fear remains a major obstacle to organizing in the South. With few union members around to teach the value of sticking together, Southern workers often know little about unions—except the horror stories they learned in school. In the campaign at Firestone Mill, for example, organizers with the United Rubber Workers found themselves confronting distorted memories of a 1929 strike at the plant.

“The union victory at the Firestone Mill in Gastonia was probably as significant historically as any campaign in recent history, because of the 1929 strike,” explains Mike Black, an AFL-CIO organizer involved in the campaign.

Black grew up in Gaston County, where he often heard the story of the 1929 strike. “The leader was organizer Fred Beal. He was a communist, didn’t make any bones about it. There was a stretch-out—more work for each operator—and the workers struck the mill. They were living in mill housing, so they were kicked out. They set up a tent city. The night the police raided the tent city, Police Chief Adderholt was killed with buckshot”

Black’s father was a Baptist preacher in Gaston County at the time. “My father attended the trial and he declares to this day that it was never proven that anyone had buckshot but the police,” Black recalls. “But it scared people to death. Every few years they would drag out the old headline, ‘Chief Adderholt Slain in Strike.’”

Firestone later purchased the mill, but the plant remained unorganized. Then, in late 1986, workers started talking about organizing a union. Their first efforts failed.

“We lost the first campaign at Firestone in 1987,” recalls Black. “We had more media coverage on that one campaign than all the campaigns I’ve ever worked on combined.”

Local press aided Firestone by printing stories about unions forcing plants to close. “There was one headline in the Gastonia Gazette announcing that Firestone was closing three plants,” says Black. “I’ve been organizing in the Carolinas for 19 years, and this was probably the most vicious attack in all of those years.”

The union successfully dispelled the plant-closing threats by demonstrating that it had worked to keep Firestone factories open in other cities. “In a moment of weakness, Firestone had circulated a letter commending the union for helping to keep the other plants open,” explains Black. “We circulated that letter to workers during the second election campaign.”

On April 14, 1988, Firestone workers voted to join the United Rubber Workers, overcoming decades of local opposition to unions.

Organizing Blitzes

The United Auto Workers soon followed up on the success at Firestone with a victory at the Mack Truck plant in Winnsboro, South Carolina.

One reason for the victory was obvious: Nearly 40 percent of the workers at Mack were UAW members who had transferred from unionized plants in Maryland and Pennsylvania. They wanted to keep their union, and they told their Southern co-workers about the value of collective bargaining. Word of the union victory at Mack Truck soon spread to other factories—including the Freightliner plant in Mt. Holly, North Carolina. “The mere fact that the UAW was successful generated a lot of press,” says Mike Black. “It didn’t start a trend exactly, but it did open the door. It contributed to being successful at Freightliner.”

Unlike Mack Truck, Freightliner employed no transferred union workers from the North. All of the workers came from the surrounding area, and they felt encouraged by the victory in Winnsboro. “When Mack Truck happened, we had been fighting for two-and-a-half years,” says Dean Easton, a maintenance electrician at Freightliner. “When they won, we got a little boost.”

The Freightliner factory stands right up the road from the Firestone Mill in Gastonia, and Easton heard the same stories about the fateful 1929 strike that Mike Black grew up with. “It was all told to me that it was the union’s fault,” he recalls. “They teach you in school, in social studies, that it was a communist strike, that people lost their lives because of the union. But we didn’t hear anything about Henry Ford working people to death on the production lines.”

Easton learned another side of the story when workers from Mack and Firestone traveled to Gastonia to assist in the Freightliner drive. Now he is taking the union message to others.

“I would liken it to a revival,” Easton says. “I’m willing to go anywhere, anytime, and testify to other people.”

More and more, union workers like Easton are participating in “organizing blitzes,” traveling to other plants to educate their fellow workers. Mary Smith works as a welter at Gardener Manufacturing near Knoxville, Tennessee, sewing plastic onto seat covers for Pontiac, Chevrolet, Chrysler, and Nissan. A single mother of three, she steered clear of the ACTWU organizing drive at first.

“I was scared at the time,” she says. “I’m a single parent and was afraid of losing my job. Then I saw that I had to choose and I came out strong for the union. I wore a YES sticker in the plant.”

Smith was soon taking advantage of a clause in her union contract to take time off from work to participate in organizing drives at nearby plants. She traveled to Irvin Automotive in Dandridge shortly before workers there joined the union last January.

“I didn’t get the full impact until I went and I saw other people struggling for something that I already had and that I was taking for granted,” Smith says. “It really made a believer out of me. I went to the union president and said I was willing to do anything to keep our union strong.”

Eyeballs on the Walls

Despite the recent groundswell of victories, workers like Mary Smith have discovered that companies have grown even more sophisticated in their anti-union tactics in recent years. Counseled by anti-labor law firms, which have done a booming business in the past decade, companies like Gardener produce expensive videos and posters designed to turn workers against unions.

“They put eyeballs up on the walls, saying the people of Warren County’s

looking at you,” recalls Georgia McCorkle, president of the ACTWU Local 2537 at Gardener. “They said we didn’t need a union here because the cost of living is lower. They held daily company meetings to propagandize against the union. At the last, I just refused to go.”

Community leaders often join companies in bitter anti-union battles. When McCorkle tried to hook up her home to county water lines during the Gardener campaign, for example, she says she was visited by a county commissioner who promised her prompt water service if she stopped her union activity.

McCorkle makes no claims, however, that just getting a union can serve as a cure-all for a sick company. Despite the union victory, she says, there are still big problems at Gardener.

“We have to stand up to sew,” she says. “People get blood clots, heel spurs, varicose veins, tendonitis, carpel tunnel syndrome, bursitis in their ankles. People are productive, but it’s a health problem.”

Still, she says, life in the factory is better since workers joined the union. Now, managers listen when employees make a suggestion or lodge a complaint. “Before they would say, ‘Shut up, sit down, and there’s the door,”’ McCorkle laughs. “Now they say, ‘All right, let’s see what we can do.’”

Just in Time

Changes in the auto industry itself have also fueled the regional drive to organize unions. In the past decade, automakers initiated a “just in time” policy, requiring suppliers like Gardener to provide goods to major auto plants on demand within 24 hours. Forced to provide parts “just in time” for production, pockets of JIT auto suppliers have grown up around Nissan, the GM Saturn plant in Tennessee, and Mack Truck and Freightliner in the Carolinas.

The new system cut warehouse costs for automakers—but it also created sweatshop conditions for employees. “JITs are difficult places to work,” explains Mark Pitt, an ACTWU organizer based in Knoxville, Tennessee. “It’s hard on everybody. A lot of overtime is not predicted, they switch from green corduroy to red leather seat covers, nobody has anything in storage—it’s real nerve-wracking.” Workers never know how long their shifts are going to be. “I’d go in at four in the afternoon and work until five or six in the morning,” explains Georgia McCorkle at the Gardener plant.

The just-in-time system also undercut company threats of moving their operations. “It is hard for companies to convince workers that they’ll be shut down and move when they have to be in a just-in-time relationship with Nissan down the street,” says Mark Pitt.

The string of union successes near Smyrna—at Bosch, GE, Coats, Doehler-Jarvis—is making some Nissan workers think twice about unions. “There’s so much fear in the Nissan plant it’s unreal,” says Emory “Red” Peeples, a UAW organizer in Smyrna. “But the victories are getting Nissan workers’ attention in a hurry. We’ve got a lot more people coming by the office.”

Once workers at non-union factories like Nissan learn of union victories, they often get angry when they find out their union neighbors or their counterparts at Northern plants are making three times as much.

“In Morrison, Tennessee, Gardener workers were making $4 an hour—compared to Gardener workers at a unionized plant in Ohio who earned $12 an hour,” explains Pitt. “They don’t feel they should be making less than somebody else just because they live in a particular JACTWU part of the country.”

The effect of a union victory often spreads beyond the factory gates. In Monroe, Louisiana, workers at the GM Fisher Guide plant who voted to join the UAW in 1976 are involved in community service and set up a college scholarship program.

Union workers at Freightliner in North Carolina are taking part in local and state politics. “We are very politically active—and we will become more politically active as we mature,” says Dean Easton, who is helping to lobby for federal legislation to protect workers involved in strikes.

Ringing Phones

As the UAW breaks new ground in the Southeast, it has turned its attention to the Deep South as well. Alabama and Mississippi are two of its fast-growing states, and nearly 1,500 workers at Pittsburgh Plate Glass and Peterbilt Trucks in Texas recently voted to join the union.

Emboldened by their success, unions are considering new initiatives—including a multi-state “campaign on the order of J.P. Stevens,” according to Harold Mclver, director of organizing for the AFL-CIO’s Industrial Union Department in Atlanta.

Mclver waved a multi-page list of prime targets, including Southern plants that have unionized counterparts in Northern states, following the Gardener and Mack Truck models. Unions are also focusing on plants with parent companies in countries that have well-organized labor movements that can apply pressure, like Belgium, France, and Sweden.

But Mclver and other union organizers acknowledge that big obstacles remain. Companies continue to “outsource” jobs—subcontracting work to non-union suppliers. Even in organized plants, like the GM Saturn plant in Spring Hill, Tennessee, companies are handing over plant maintenance jobs to non-union firms.

Unions say they also remain strapped for the organizers and money they need to respond to the increasing number of requests for help. Since the UAW won at Mack Truck last year, the phone in the Southern regional office hasn’t stopped ringing. Workers want to know how they can organize a union in their plants.

“I just can’t answer all the calls for organizing assistance,” complains Bob Miller, director of the office.

Of course, after more than a decade of setbacks, that’s the kind of problem union organizers like Miller are all too glad to have.

Tags

Ellen Spears

Ellen Spears is a writer and a former chassis department worker at the General Motors plant in Doraville, Georgia. (1990)