Holding Allie

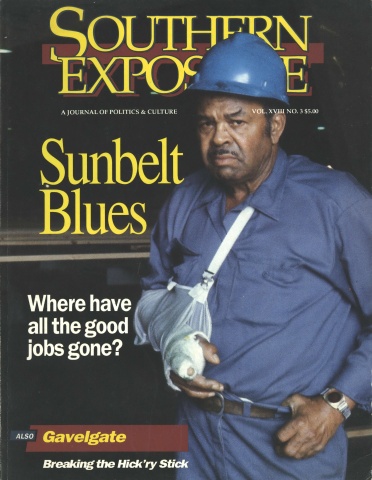

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 3, "Sunbelt Blues." Find more from that issue here.

When I went to get you the day before Thanksgiving, Jenny was standing grim-faced by the porch swing. You were sitting on a mat at her feet, sobbing and waving a dead leaf.

“Any better?” I asked.

“This has been the worst day so far,” Jenny said.

At the sound of my voice, you looked up and let out a cry, twisting your right hand in that way you used to do—like you were cracking a safe. I picked you up.

“I don’t know what to do,’’ Jenny said. “She’s been screaming from the moment you left until about fifteen minutes ago. She wouldn’t eat or take a nap or anything. I feel like I’m about to snap.”

You craned your neck to peer into my face. “Buh,” you said. Even then, you had my chin and your mother’s eyes. Your hair was straight and blonde and not yet long enough for people in grocery store lines to stop saying, “He must be hungry” or “He must be cold.” Sometimes I would go to the store alone, leaving you with your mother. I always felt reckless when I was in a car without the two of you, like I was on mission. The grocery store was only two miles away.

“Well, I don’t know, Jenny,” I said. “If it gets to where you just can’t stand it any longer ... I didn’t finish the thought because I was afraid she would take me up on it. I was already in trouble at the school for not keeping regular office hours. If I started canceling classes, they’d fire me.

“It’ll get better,” Jenny said with a weak smile. “It can’t get any worse.”

Please, I wanted to say. Give her a little more time.

Instead, I tied the strings of your hooded jacket under your chin and wished her a happy Thanksgiving. Then I carried you across the street to our house.

At first, the arrangement had seemed perfect. Jenny knew our situation and had asked if she could help by keeping you while I was in class. It was hard to get her to accept money, but she finally did. She had three school-aged children of her own and a degree in early childhood education. Her husband, Greg, was an ophthalmologist. He was my age, late thirties, and on a fellowship at the University Eye Clinic. He and Jenny had been trying to figure out where to set up his private practice. There had been some good offers, which they’d narrowed down to Johnson City, Tennessee, and Savannah, Georgia. I kept hoping they would stay in Birmingham, but if they did, I was afraid he’d open a practice in a better neighborhood and move to Mountain Brook, and Jenny wouldn’t be able to keep you anyway.

What Greg really wanted, though, was to be a country-western songwriter. One night he and Jenny had us over for barbecued ribs, and afterwards he played a cassette of a song he’d written. It was a ballad about the crew of a B-52 that never came back from a mission over Vietnam. I was surprised at how professional the tape sounded, and I told him so. Greg seemed pleased. He said that he had gone into medicine just to make ends meet until his songs hit it big in Nashville.

I’d never known a doctor like that. And Jenny was always talking about going back to work so they could afford to redecorate their modest frame house, even though it was clear they wouldn’t be living in it much longer. Our neighborhood was older, urban, middle class—the perfect place for schoolteachers and social workers like me and your mother, but not what you’d expect for the family of an ophthalmologist.

I’d rarely see our other neighbors unless there was an explosion at the dynamite plant in Bessemer. Then they’d all appear at their back doors, in fine spirits, and shout to one another, “Whaddaya think that was?” or “Wherediya think that came from?” One of them, usually Joe Autrey, would say he was going to turn on his police scanner to see what he could find out, and everybody would go inside, and that’s the last I would see of any of them till spring.

Buddy Lawler was different, though. He lived next door. Before his wife Thelma died and he moved in with his son by a previous marriage, we ‘d have long talks while we were supposed to be raking leaves or cutting back the roses. He’d tell me about the time he spent on a troopship in World War II. He’d been a baker in the ship’s mess, and after the war he worked for a bakery here in Birmingham until he retired. I asked him what it was like to be on a ship in the Pacific during the war. Buddy said it was hot like a kitchen anywhere, only smaller. Once in a while he’d get to go on deck at night. The ocean was big and dark, he said. That’s how Buddy talked. After Thelma died, for instance, the first thing he said to me was: “I miss her.” This was ten days before you were born. After that, he went to live with his son until the house sold. It was on the market for over a year.

One night, a Sunday, I was grading paper slate when I heard the sound of gunfire from somewhere in the neighborhood. Your mother stirred, but I don’t think you or she woke up. I went out on the front steps. There was a man running through the yards across the street. In front of Jenny and Greg’s, he jumped into a waiting car—its engine was idling, although the headlights were out. The car took off at a leisurely pace. I ducked. After the car had passed, I tried to get the tag number but couldn’t. Then I waited, crouched behind the banister, breathing hard. There weren’t any more shots. I walked around the block. Nobody’s lights were on. I was afraid I’d imagined the whole thing, but when I got back to the house I called the police anyway. Except for mine, they hadn’t gotten any reports of trouble, but they were going to check things out .Later I saw their patrol car meandering through the neighborhood, its searchlight touching on Jenny and Greg’s door and Buddy’s and Joe Autrey’s and all the others, including ours.

The next day, when I took you across the street to Jenny’s, she told me what had happened. Somebody had tried to steal a car from the Autreys’ carport. The Autreys opened fire from their bedroom window. Both of them had guns. For some reason, the thief continued to try to hotwire the Autreys’ car. That’s why there were so many shots. None of them hit him. He must have been the guy I saw running down the street, a very lucky man.

I wanted to tell Buddy all about the shooting, but then I remembered he didn’t live in the neighborhood anymore. His house was empty. The For Sale sign was still up, although he’d told me the last time he had come by with his son to clean out the garage that the house was under contract to a young couple.

When I finally did see him again, the contract had fallen through and I’d forgotten about the gunshots, but Buddy had his own story: “Somebody broke into my house. They cut a screen to get in. Did you hear them?”

“No,” I said. “What did they take?”

“Nothing,” he said. “There were some old bills and letters in a closet. They looked through them, but didn’t take anything.”

“That’s good.” “It still gives you a funny feeling,” Buddy said. “Even when you don’t live there anymore.” And I agreed. I wished he hadn’t decided to move in with his son, but I guess he didn’t have any choice. His heart was bad and he’d just lost his wife. Still, for our sake, I wish he had stayed.

Just the other day, I heard some statistics about old people that surprised me. Most of today’s old women went through their peak child-bearing years during the Great Depression. A third of them never had children, the highest ratio before or since. I didn’t catch the reasons, but I suppose they had to do with economics. Maybe the women put off having kids because they knew they couldn’t support them. Maybe an insufficient diet resulted in decreased fertility. Whatever the case, it was an interesting fact that I hadn’t known before. It made me think of Buddy’s wife Thelma, who never had any kids of her own.

It got better for you and Jenny just before Christmas. I don’t know what did the trick, but you were like old friends for a while. You stopped crying after I left, and you let Jenny feed you and rock you to sleep. You even sat in her lap and listened while she read to you.

“I think everything’s going to work out now,” Jenny smiled.

“Boy, that’s a relief,” I said. “You don’t know how much we appreciate what you’re doing.”

“Well, let me get the empty bottles,” she said, and when back out, she was blushing. “Today I even had the feeling that she liked me.”

“Of course she likes you,” I said. ‘Tell Jenny how much you like her.” You stretched your arms out. You yawned.

First thing when we got home, I called your mother at her office. “It’s working!” I said.

“Thank God,” she answered. It was as though we both knew our lives were going to be normal now. Or nearly normal. When I think about what it was like for my parents—Mom staying home all day with us and Dad pulling into the driveway at exactly 5:30, supper on the table, the vacuuming done, it’s as though I’m looking at a painstakingly carved antique clock, a beautiful curiosity.

But it didn’t resemble our life at all. Our moods depended entirely on how you were doing at Jenny’s. The bad days, we felt doomed. One of us would have to quit work, we’d say, but we knew a single paycheck would barely cover the house note and electricity. So we’d put ads in the paper that went mostly unanswered. Sometimes a voice with a twang would call about the ad, and your mother would use a day of vacation so she could check the girl out.

“What was she like?” I’d ask when I got home. “She had this funny haircut,” your mother would say, “and she lives across town and doesn’t have a car.” So we’d never get back in touch with her. But on the day Jenny told us things were working, your mother and I felt reborn. We could make plans. We even talked about another child.

“I love Jenny,” I said.

“Are you attracted to her?” your mother asked.

I stopped to picture Jenny in my mind. Tall. Pleasant smile. Big gray eyes above broad cheeks. “No. It’s not that,” I said. “I mean I really love her.”

“I know,” your mother said. “I love her too.”

Over the Christmas break, Jenny and Greg and the kids visited their families in Florida. Since I didn’t have class, I was able to keep you all day, although your mother sometimes took you to her office in the afternoon. We felt we’d reached a perfect equilibrium. It lasted until Jenny returned and the new semester began. Then, when I left you with her, you started crying again. This time, though, there was no improvement. If anything, the situation got worse. It was nobody ’ s fault. You just wanted to be with your mother and me, the most natural thing in the world.

“I have to talk to you,” Jenny said on a day when I had run late picking you up. I sat down on her sofa. You were in my lap—tear-stained, but happy now.

“Please stop banging on the piano,” Jenny said to her younger daughter, Laura.

“But...”

“Don’t talk back,” she said.

“I wasn’t. I was just going to tell you that... that I read a book today.” Laura had a learning disability. Her older sister, Rachel, was gifted. They were in different special classes at the same school, but they were out that day for a state holiday that the university didn’t observe.

“What book?” Jenny said. “This... this book... about...”

“Tell me later, OK?” Jenny said. “I really want to hear about the book, but later.

“The fact is,” she said to me without taking a breath, “I’m at the end of my rope.”

“I understand.”

“Your daughter’s inconsolable. Nothing I do helps. I can’t get any housework done. When the kids get home from school, I’m too exhausted to give them the attention they deserve. Greg thinks I should see a doctor, and he is one.” She paused. “It’s not just her, it’s everything. We’re both half-crazy trying to decide where to locate. She’s a lovely child, she really is, and if she were like she is now, when you’re here, it would be a joy to keep her. But I have my own life.”

“I understand,” I said.

“There’s no reason to feel like you’re letting us down.”

“But I am,” she said, and her eyes welled. “I’m leaving you in a lurch. And I just feel like she hates to come over here, hates to see me.”

“No, no,” I said.

“Momma?” “What, Laura,” Jenny said.

“Can... if Trinket comes over, can we play, you know?”

“In your room? Yes. But don’t turn the record player up so loud, OK?”

“OK.”

“Sometimes I think she ’ll get back like she was before Christmas,” Jenny continued. “It seemed so good then. But when I really think about it, I realize how deceptive that was. It was only good relative to what it had been like before.”

“I know what you mean.”

Jenny looked at me and then glanced away. “It just wasn’t like I thought it was going to be,” she said.

“Please don’t worry,” I said. “We understand. And we can’t thank you enough for what you’ve done.”

I got up to go. Jenny gathered some toys from the coffee table and put them into your bag.

“Do you need any help getting her across the street?” she asked.

“No, but thanks. And tell Greg — Savannah. It’s a beautiful town.”

“You’ve been there?” I nodded.

“He’s leaning toward Johnson City, because it’s closer to Nashville.”

“Well, we’ll have to get together and talk.”

“Yes. Please. Let’s do. And if you get in a pinch and need a babysitter for an evening out...”

“Of course we will. Thank you, Jenny.” And I carried you outside.

It was nearly dark. I waited at the curb, even though there were no cars coming. I’d felt this way about other women I’d loved, and I knew I’d get over this feeling, too.

From the curb I could see the For Sale Sign in Buddy Lawler’s front yard, and what I remembered at that moment was the Sunday on which his wife Thelma died, ten days before you were born.

On that day your mother and I had seen the firetruck in front of Buddy and Thelma’s house right before we left for church. We both thought it was his heart. I said I would go next door and see if I could help, although there was nothing I could have done. Your mother finished dressing. She was having trouble finding something that fit. She had already passed her due date, and even the enormous black dress Jenny had loaned her had begun to ride up in front.

It was a morning like the one on which you were to be born—crisp and bright, too cold for Birmingham, but filled with all sorts of promise. The idling firetruck sent up plumes of white exhaust. Buddy’s front door was ajar, so I didn’t knock. I just opened the screen door, letting in a gust of cold air. The living room was unnaturally warm, a hothouse. Buddy sat in a rocker in the center of the room. He looked pale and stricken. The Autreys stood on either side of him. Mrs. Autrey’s red hair was at all angles like a fright wig. Joe still had on his bedroom slippers. They didn’t look the type to shoot at car thieves.

“Are you OK, Buddy?” I asked.

He nodded, but it was clear he wasn’t. He leaned his head back, and his breath came shallow and light. Around his lips, the skin was blue. The scar on his neck where a tracheotomy tube had once been inserted shone slick and white under the light from the open door.

“It’s all right now, Buddy,” Mrs. Autrey said as she stroked his temples.

“Is there anything I can do?” I asked.

Buddy didn’t open his eyes. “They’re already doing everything they can for her.”

That’s when I understood. The firemen were in the kitchen. I glanced in long enough to confirm that it was really Thelma stretched out on the floor. I couldn’t see her face for the rubbery coats of the firemen, only a swatch of yellowish-white hair. Her glasses were lying on the floor under the kitchen table. The air smelled like slightly burnt toast. The firemen were talking swiftly and softly. One of their beepers went off, and Thelma made a weak, bleating sound.

Then the screen door rattled. I turned and saw your mother at the front door, shielding her eyes so as to see into the living room. “We’re running late,” she said when I went to the door.

“I know.”

“Sunday School’s already started.” “I’ll be out in a second,” I said.

“Is he all right?”

“Yes.”

“Then come on. We’ve got to hurry. Hi, Buddy,” she said in a louder voice.

He lifted his hand as if to wave. “Hi, honey,” he said.

“Let me know what happens,” I said to the Autreys before I opened the screen door and followed your mother into the blast of cold air. Leaves swirled around her feet. Her ankles were splotchy and swollen twice their normal size.

“It was Thelma,” I said. “I think she had a stroke. She’s still alive, but it doesn’t look good.”

“I thought it was Buddy,” your mother said without a trace of surprise. I didn’t believe her for a minute. I thought it had been insensitive of her not to come inside. I thought it was because she was pregnant and full of herself and just didn’t want to take the time to watch a childless woman die. I ran through a catalogue of minor slights I thought I had suffered during the pregnancy. I was angry all through church. I kept my eyes open during the prayers.

That afternoon Thelma did die, and your mother baked a casserole and carried it next door. Buddy was surrounded by his son’s family and a few old friends, most of them retired from the bakery where he had worked. He introduced your mother as his little girl. They laughed. I suppose it made everyone happy to see a pregnant woman so soon after a death. When your mother came home, I apologized to her for the way I had been thinking lately. “There’s nothing wrong with thinking things,” she said. “We all think things.” And nine days later, you were born.

Allie, it is not an exaggeration to say that we loved you before you were born, before you were even conceived. This is just in the nature of longing, particularly when it’s for something that you think you’ll never have. We thought we’d never be able to have a child. We had been trying for almost ten years. And the passion your mother and I felt for one another was too strong and too dangerous for us to keep it between ourselves forever. Eventually, without you, it would have sent us spiraling away from one another. What I’m saying is that we needed you more than you have ever needed us. When Jenny said she couldn’t keep you anymore, it was a minor inconvenience in the long run. We juggled our schedules. We made arrangements. We kept our jobs. Everything worked for the best. But on that afternoon when I stood on the curb before carrying you across the street from Jenny’s for the last time, I felt as though the world had caved in on me. It was early January. The sun had fallen behind the houses at the end of our block, and a line of migrating blackbirds was following the sun across a sky that was absolutely colorless. The line of birds seemed to have no beginning and no end. Unless you looked closely, you couldn’t even tell whether they were moving or not. I think this is what is called despair. But I did not call it that then. I just did what came next. I took you inside and fixed something for us to eat. I turned on the stereo. We waited for your mother to come home. She was running a little late because of a meeting. While you played with your books and blocks, I looked out the window, watching for her car. Our house was on a hill, and I could see the whole neighborhood. Except for Buddy’s, the lights were on in all the houses on the block.