This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 3, "Sunbelt Blues." Find more from that issue here.

Three years after the largest layoff in city history, Durham workers still struggle to make ends meet.

For 13 years, Fay and Michael Riggs worked together at the huge American Tobacco Co. factory in Durham, North Carolina. Fay operated a cigarette machine, making sure it was up and running, clean and full of paper. Michael, her sweetheart since junior high school, drove a forklift on the docks outside the plant. They made union wages: a combined $27 an hour, no small sum for two high-school dropouts.

“It got us a home,” says Fay. “Friends of ours couldn’t afford a down payment or make a house payment.” They bought camping equipment, even a boat. “It gave us more pleasurable things than just the needs.”

More important, their jobs gave them community. The factory was a veritable network of aunts, uncles, cousins, and friends — 1,000 employees, some of whom had labored together for decades. Michael’s mother and stepfather worked there, along with Fay’s sister. “There wasn’t a soul up there that didn’t have kin there,” Fay says.

That network transcended the factory walls. Along with four or five other couples from American Tobacco, the Riggses would camp on Kerr Lake, sometimes blowing $200 in a single weekend. Michael played softball with the other men in his department. “If anyone was sick or there was a death in the family, the employees stuck together,” Fay says.

Then—without warning—that life came to an end. On August 26,1986, American Tobacco’s managers told all the first-shift employees to turn off the machines and report to the cafeteria. “People were talking on the way up there, ‘They’re trying to get us to give more money to the United Fund,”’ recalls Michael. “But we knew what it was all about.”

His fears proved correct. The plant management had called the meeting to announce that the 100-year-old factory, which produced Lucky Strikes, Pall Malls and Carltons, would close the following year.

American Tobacco was experiencing record growth that year, and its parent firm, American Brands, saw its sales increase to $8.5 billion, up from $7.3 billion the year before. Yet officers at American Tobacco headquarters in Stamford, Connecticut, had decided that the Durham plant was operating below capacity and could be consolidated with a facility in Reidsville, North Carolina.

“The first thing that popped into my mind was that we had to go to Reidsville,” remembers Fay. They visited the town on the Virginia border, found it “not very desirable,” and decided they didn’t want to uproot their two sons and leave the boys’ grandparents.

So Michael bought a trencher and did freelance ditch-digging, while Fay stayed home with the boys. She looked for work —but no one wanted to hire a worker accustomed to earning $ 14 an hour. “I told the man where I applied, ‘I know I’m not going to make $ 14, so I’ve got to start at the bottom somewhere.’”

Eventually, they both found work with a pumping company owned by her uncle. She keeps the books, while he travels around the area servicing well pumps. Their combined starting wage was $12 an hour, a 55 percent cut from their American Tobacco jobs. They receive no medical or dental insurance, and a fraction of the vacation time they once got

What happened to the Riggses happened to many of the workers at American Tobacco. Three years after the largest layoff in Durham history, the shock waves still ripple through the community. Separated from family and friends, many of the former factory workers have been forced to settle for lower-paying jobs in the service sector. Taken together, their stories reveal a larger shift in the Southern economy, as hometown industries across the region have been boarded up by Wall Street powerhouses.

The Riggses like their new jobs and enjoy working together again. But they miss their friends. Many moved to Reidsville to keep their jobs, and when they get together—which isn’t often—it feels awkward. “Everyone’s got their different worlds,” Fay says.

“I keep saying we’re going to get up one Sunday morning and drive up there and see them, but we never do,” adds Michael. “Someday I will.”

Golf Balls and Pinkertons

Driving into downtown Durham from the south, the first and most imposing building a motorist sees is the American Tobacco factory: a brick complex five blocks long, bordered on two sides by almost a half-mile of razor fencing. A whitewater tower and brick smokestack rise from the four-story plant, each bearing the bull’s eye logo of Lucky Strike cigarettes.

Now the complex sits empty, one of hundreds of factories throughout the South that have shut their doors in recent years. A survey of eight Southern states by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics turned up 549 plants that shut down or held mass layoffs the same year as the American Tobacco closing, throwing 134,580 people out of work.

But the American Tobacco complex was always more than a factory — it stood as a monument to the city’s raison d’etre. Durham was founded as a tobacco town, and cigarettes were the main business venture of Washington Duke, the endower of Duke University and patriarch of the city’s most famous family.

As Duke’s empire grew, so did Durham. Before the U.S. Supreme Court ordered it to break up in 1911, American Tobacco had gobbled up its major competitors and had a lock on the American cigarette market. Seventy-five years later, the firm had taken a back seat to such giants as R.J. Reynolds and Philip Morris.

Still, it remained a mainstay of Durham’s economy. With a unionized work force, it offered wages exceeding $ 19 an hour for some skilled employees. Durham natives without high-school diplomas could stay in town and find well-paying jobs, often side-by-side with their families.

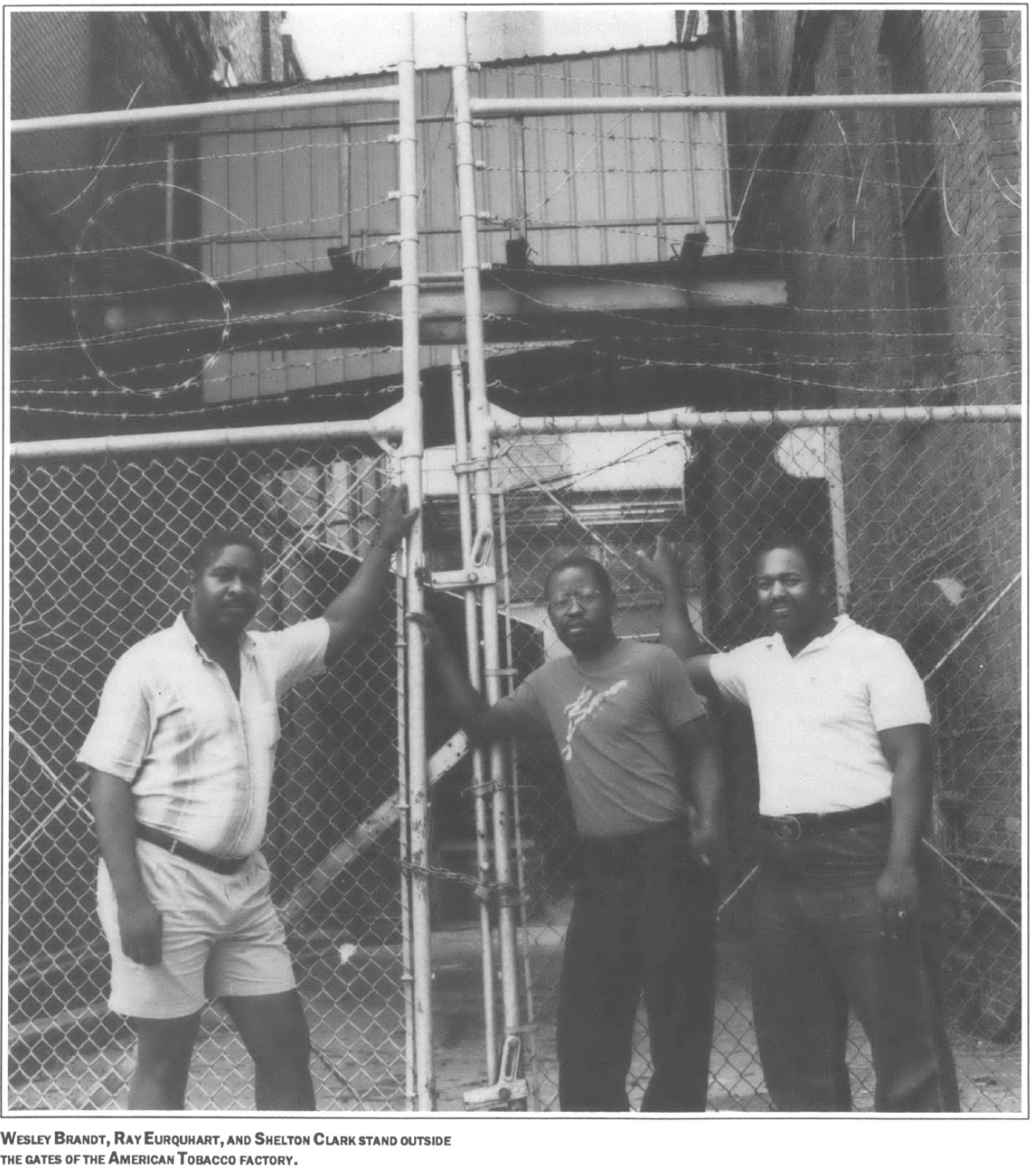

“There was a joke that if certain people died, they would have to close the factory that day because so many people from the family worked there,” says former American Tobacco millwright Ray Eurquhart.

But while factory life centered around family and community, American Tobacco had long ago left the town where it grew up. Now the company belonged to American Brands, a giant conglomerate based in Old Greenwich, Connecticut that also owned Jim Beam bourbon, Titleist golf balls, Franklin Life Insurance Co. and Pinkerton’s detective agency. When the company decided to close the plant, the decision was made in Connecticut. No one consulted workers, city officials, or union leaders in Durham.

Company officials say that community and history fell victim to bottom-line economics. According to Robert Rukeyser, senior vice president for American Brands, the domestic market for tobacco had declined while improved technology enabled fewer machines to produce more cigarettes. As a result, both the Durham and Reidsville plants operated at below capacity. “It was uneconomical to continue producing at two facilities,” he says.

For Durham workers, the plant closing meant the death of the community. Overnight, the city lost 1,000 jobs and more than $700,000 in annual tax revenues. Nearly 260 hourly employees transferred to Reidsville. Some moved to the small one-industry town; others live in Durham and commute the two and-a-half hours each day.

But most of the Durham workers parted company with American Tobacco when it closed. Some started their own businesses or found satisfying work in other fields. Many went to work for Duke University. Others have drifted from job to job, finding only low-paying or temporary work. ‘There are some real success stories and some real sad stories about substance abuse and people who are just wandering,” says Eurquhart.

A Clean Start

In many ways — thanks in large part to the presence of a union — the closing created less trauma than others across the South. American Tobacco gave workers a year’s notice, and the union and company negotiated a shutdown package that made the transition as easy as possible for many. “American did not leave us like some other companies where you get to work the next day and there’s a big padlock on the door,” says Ruby Holeman, a former cigarette inspector who now works as a nurse at a convalescent home.

Along with severance pay and dividends from its profit-sharing program, the company offered training programs for the workers it was about to dismiss. Employees could go back to school for their high-school diplomas, or they could take specialized courses at local community colleges at American’s expense. Brokers came into the plant and conducted seminars on investing money and running small businesses. Some of the workers could take advantage of those opportunities and build better lives for themselves.

Wesley Brandt was at home asleep when his day-shift co-workers learned about the plant closing. He worked evenings and slept mornings—and on that August morning, a friend’s call jarred him from sleep. “He said, ‘Man, have you seen the paper?”’ Brandt recalls. When he heard the news, “I felt like the rug had been pulled out from under me.”

For Brandt, the closing could only mean a pay cut. In his 13 years there, he had climbed from a general laborer to a mechanic, adjusting the equipment that packed the cigarettes. He made over $19 an hour—“the top of the scale,” he says.

“I didn’t know what I was going to do. I knew I was going to work somewhere else, but I knew there was nowhere to go and make the same money I made at American.”

Brandt began attending the small-business seminars sponsored by American Tobacco and decided to start his own business. “When they gave the seminars, the brokers were real salespeople,” he says. “They gave us a list of local-owned businesses that were up for sale.” Brandt arranged with one of the brokers to buy a failing 24-hour laundromat in nearby Carrboro.

“It was a real dump. A lot of the equipment was old and had been vandalized. What hadn’t been vandalized had just been worn out,” he says. “You had a lot of drifters who used it to come in out of the cold.”

Brandt had no money for renovation, but he worked for six or seven hours a day, cleaning up and keeping the vagrants away. “People began to come in because they knew I was trying to turn the place around,” he says.

After eight months, Brandt had saved enough money to take out a commercial loan and revamp the laundromat. Now the Carrboro Laundromat and Dry Cleaners is stocked with new Speed Queen washers and shiny Wascomat Senior Triple Loaders. A television plays religious programming and home shopping, while a bulletin board displays notices for the NAACP, the U.S. Census Bureau, and a customer who wants to buy used wedding dresses. Brandt sits behind the counter accepting clothing for a local dry cleaner.

Brandt is turning a profit—though he works 60 or 70 hours a week and still earns less than he did at American Tobacco. Nonetheless, he says he’s at greater peace with himself than ever before. “I’m my own boss. When I open the doors in the morning now, I’m opening the doors for myself. I’m not making big profits for someone else.”

“Bigness is Better”

It would be simplistic to say that a mere business decision made in Connecticut disrupted thousands of lives in Durham. In a larger sense, the American Tobacco plant closing resulted from enormous changes in the South’s economy: the decline in manufacturing, the rise in the service sector, and the trend toward bigger and more diversified corporations.

That strategy of owning many unrelated companies—called “diversification”—is common in the United States, particularly in the tobacco industry, where consumption has dropped over the past 20 years. American Brands pursued that strategy feverishly, buying companies, then turning around and selling them again. Since the mid-1980s, American Brands has gone on a $3.8-billion buying spree, while selling off $2.5 billion in “non-strategic” divisions, says vice president Rukeyser.

The corporation has forayed into liquor, hardware, office supplies and insurance, while getting out of biscuits and detective services. It deflected a takeover bid by a company called E-II Holdings by turning around and swallowing up the aggressor company for $ 1.1 billion.

“Today I take the position that bigness is better,” American Brands chairman William Alley told the Stamford Advocate two years ago. “Competing in international markets requires largeness, financial acumen and the ability to get in and stay in developing markets.”

All these high-finance maneuvers were made possible by workers like Wesley Brandt and the Riggses. American Brands makes 65 percent of its operating income from cigarette manufacturing, and the corporation plows that money into other business ventures. “Tobacco companies are cash cows,” says Jack Maxwell, a securities analyst with Wheat, First Securities in Richmond, Virginia. “They produce all this extra cash that they use to increase profitability.”

In the complex web of ownership, American Tobacco was a division of American Brands until January 1986. Then the parent corporation reorganized itself: American Tobacco became an independent subsidiary, operating with more autonomy than in the past. A company spokesperson told The Wall Street Journal the reshuffling would “provide a more favorable vehicle for future acquisitions.”

Within eight months of the changes, American Tobacco decided to board up its Durham plant.

The factory closed on August 26, 1987. That year represented “the best year in our history,” according to American Brands. Earnings increased 43 percent, while revenues broke another record — this time $9.2 billion.

Taxi

1987 didn’t prove so rewarding for American Tobacco workers. Five months before the company announced the Durham plant closing, J.P. Stevens began closing the city’s last big textile mill, throwing 700 employees out of work. They joined 445 who found themselves jobless when General Electric shut down its Durham turbine plant.

Some of the workers left Durham altogether. Linda and Robert Ferrell had just bought land in the country and were planning to build a new home—and then the announcement came. In order to keep their well-paying American Tobacco jobs, they moved to Reidsville and transferred to the night shift. “You don’t live somewhere half your life and make friends and that’s where your roots are, and not miss it,” says Robert “I don’t want to imply that I’m tickled to damn death here.”

Others opted to commute. Every work night, Eddie Hunt starts preparing for work at 9 p.m. in order to get to Reidsville by 11. “I don’t sleep with my wife five nights out of the week,” he says. And when his son plays in evening ball games, “I can only go to a half-hour of them, and then come home.”

What’s hardest for Hunt, though, is how the plant closing broke up his tight circle of friends. “All us boys, we’d go out to lunch — it was like high school kids together. We’d cut up, we’d have fun. Now it seems like we’ve broken up. You see them at the mall or if you go out to eat, but it’s not the same.”

Those who stayed in Durham found the job market glutted. There were no manufacturing jobs to be had, and even low-paying service-sector work proved hard to find.

“If you didn’t have any skills at my age, 41, they look at you and say, ‘What can you offer me?”’ says Carolyn Williams, who operated a cigarette-packing machine at American. While she looked for work, she was forced to give up her rental house and move into her mother’s home with her teenage son. Although she went back to a community college for secretarial training, all Williams could find was a $ 12,000-a-year job in a local law office.

Even workers who had skills found their abilities couldn’t always be transferred. Shelton Clark had finished a four-year apprenticeship at American to become a millwright: a mechanic who installed motors, did carpentry, laid bricks and made conveyors. “To be a millwright at the American Tobacco was the top job in the factory,” he says. “It made me feel a lot of responsibility and at times a lot of pressure to do good, and always to learn.”

Clark’s $40,000 annual wage enabled him to take his wife and three children to Atlanta every few months to watch Braves baseball games. They bought a modest brick house on a quiet cul-de-sac and clothed the children well.

When the announcement came, “it was like a numb feeling, like maybe it didn’t happen.” Still, with his millwright training, Clark was optimistic he’d find a decent job.

He was wrong. He could only find a temporary job at IBM, packaging computer components. He made $6 an hour, and his severance pay tided the family over.

When the job ran out, the doldrums set in. For six months Clark looked furiously for work. He answered ads for maintenance workers, but the jobs required electrical experience. “A lot of jobs, they didn’t want to hire me because I worked at American Tobacco and I made a lot of money,” he says. “I was told by prospective employers that I wouldn’t be happy at that job because I wouldn’t be making $19 an hour. I explained [that] all I wanted was a decent-paying job with some benefits.” To make ends meet, Clark did maintenance at Duke University and helped a friend make ceramic figures to sell as Christmas gifts. Finally, he found a job driving a taxicab, averaging $5 an hour. Now, Clark gets in his cab every afternoon and drives around the city and the airport until he has earned his share of the household income. Usually that means coming home at 3 a.m., though sometimes he has to stay out until 5. “I dread working in the city because of the possibility of getting robbed,” he says. “The folks in the city take the cab to pick up drugs. It’s something I kind of hate to do.”

And the stress has “worked on my nerves,” he says. His temper has worn thin, and he worries because the family cannot afford medical insurance. “As long as I stay healthy, I’ll be likely to survive pretty well,” he says. “I can’t afford to get sick.”

“I was looking forward to retiring at the factory,” Clark says. “I would have had a great retirement, but they just shut the doors down on me. The plant was good to me—but then again, the plant wasn’t, by closing.”

A Bitter Diploma

The American Tobacco factory sits idle now—but not for long. In August, Durham City Council approved a plan by local developer Adam Abram to convert the 24-acre site into American Campus — an emporium of shops and offices. “I think this is a doggone good project,” Mayor Chester Jenkins told the Raleigh News and Observer.

The conversion of the tobacco plant marks a fitting end to the tobacco factory founded by Washington Duke. Just as American Tobacco’s parent company has diversified beyond manufacturing into service industries such as insurance, so have the workers who toiled there. They now work for law firms, taxi fleets, and nursing homes—businesses that don’t produce tangible “products”—making far less money than they did in the factory.

Now, with its conversion into a shopping and office complex, even the American Tobacco plant will join the service sector. And one of the tenants at American Campus will be the institution that Duke financed with his tobacco money: Duke University. The plan calls for Duke to rent 125,000 square feet for classrooms, labs or offices.

Unlike the tobacco company, Duke University is part of the service economy. It pays its workers wages well below what American Tobacco paid, even for specialized jobs such as air-conditioning maintenance. “With $9 an hour, you make it, but you don’t have any extra. A lot of our buying habits we had to change,” says John Thomas Riley, one of the many former American Tobacco workers who now work for the university.

For workers like Riley, the transition of their old workplace—from hometown factory to elite university — may be the most biting irony of all.

Tags

Barry Yeoman

Barry Yeoman is senior staff writer for The Independent in Durham, North Carolina. (1996)

Barry Yeoman is associate editor of The Independent newsweekly in Durham, North Carolina. (1994)