This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 3, "Sunbelt Blues." Find more from that issue here.

Lilburn, Ga.—It was the year after Jimmy Carter lost the election that Greg Muller made his first visit to the principal’s office. His teacher, who had accused the seven-year-old boy of knocking over a classmate’s blocks, had marched him there for punishment. Greg was lightheaded with fear. He had heard stories from other children about painful beatings by the principal, and walking down the hallway of Knight Elementary — a large school in the heart of affluent Gwinnett County—he was afraid he might faint. “My hands were sweating and my arms and legs were so tense they hurt,” recalls Greg, now 14. “I was terrified.”

In the office, he began to cry. After shouting for the boy to hold on to a chair and bend over, the principal slammed the paddle against his buttocks so hard it lifted him off the ground. Then she hit him again. “It felt like someone had stuck a hot iron against my skin,” recalls Greg. Although he says a little girl had actually knocked down his classmate’s blocks, he didn’t even try to protest his innocence. “I don’t mean to be rude or anything, but you grown-ups never listen. I just knew it was going to hurt really bad.... And it did.”

What Greg didn’t know was that he was to be one of the last students ever hit at Knight Elementary: in 1983 the school abandoned corporal punishment once and for all. More recently other school districts, cities, and states have followed suit, thanks in large part to pressure from parents and advocacy groups such as the National Coalition to Abolish Corporal Punishment in the Schools.

The practice is still legal in thirty states, including every Southern state except Virginia. Federal records show that at least one million schoolchildren are paddled each year—some suffering severe bruises, broken bones, and concussions —and critics say the real number may be far higher. “Show me a principal who reports every paddling and I’ve got some land to sell you in Florida—and it’s all underwater,” snorts John Kennedy, deputy school superintendent in Jacksonville.

Although some school administrators argue that corporal punishment is necessary to keep order in the schools, others are slowly recognizing what studies have long shown: that paddling not only scars children emotionally and physically, but may contribute to rather than lessen school vandalism and fighting.

With corporal punishment under siege, and with more principals and teachers laying down their paddles, the question becomes: What kind of discipline will replace the belt, the switch, and the one-by-four board?

The vast majority of schools, including those that continue to paddle, depend on an authoritarian “obedience” model of discipline—one in which students are expected to obey teachers without question or be punished. The most popular such model is Assertive Discipline (AD), a system of rewards and punishments designed to “make” children behave. But critics charge that AD humiliates students and teaches them that they are not responsible for their behavior: Adults are.

A handful of schools, meanwhile—including Greg Muller’s alma mater, Knight Elementary —are quietly implementing a “responsibility model” of discipline, one in which students learn to take control of their own behavior. Such an approach turns traditional ideas about obedience and punishment upside down—and has left some teachers in Georgia and elsewhere apprehensive. “I don’t like paddling, but without it my kids would go wild,” one teacher from Texas says. “They’d string me up and nail me to the wall.”

What happened at Knight after it threw away the paddle might change his mind.

The New Attitude

When Dr. Burrelle Meeks took over as principal of Knight Elementary in the summer of 1983, the suburban school was plagued by more than its share of rowdiness: students fighting on the playground, throwing food in the cafeteria, smarting off to teachers, and disrupting assemblies with boos and catcalls—all offenses punished by paddling in many Georgia schools. But Meeks, who’s 52, knew privately that one thing was certain: She was not going to hit children.

“That’s what many people expected a principal to do,” she recalls, “and many other principals I knew had advised me never to let anyone know I wouldn’t paddle. So I was coming in with a little fear and trembling, to take over a role I didn’t believe in.”

Meeks herself had not always opposed corporal punishment. Her upbringing in south Georgia was a loving but traditional one that included spanking; as a parent, she occasionally spanked her own children, though not her students. “I didn’t know anything else to do when I was young,” she says. “You tend to do what was done to you.... But you change, and I came to feel that hitting children teaches them that it’s okay to hit people if you’re bigger or stronger.”

Although she feared some “spare the rod, spoil the child” sentiment at Knight, Meeks instead found a kindred spirit in school guidance counselor Sharon Wilson, who also opposed corporal punishment. Most of the teachers disliked paddling, too, and they were troubled by inconsistency in discipline from class to class. To help look at alternatives, Meeks flew in Barbara Coloroso, an ebullient discipline specialist from Colorado whose basic philosophical tenets include “I will not treat a student in a way that I myself would not want to be treated.”

During a two-day workshop with Coloroso in the summer of 1983, the new principal sat down with the Knight faculty and staff and hammered out a schoolwide discipline program— “discipline with dignity,” a system of clear, simple rules and consequences that allowed students to take responsibility for their own actions. The six basic rules were no hitting, no stealing or damaging property, no throwing objects such as books or rocks, no defying authority, no abusive language, and no continuous disruptive behavior. Students who broke class rules would go to a “time-out desk” where, instead of just cooling their heels, they would write out a plan for how they could avoid breaking the rule again.

But if Knight Elementary was no longer an autocracy, the workings of democracy, as they say, had to be learned. When Meeks asked a couple of eight-year-old students what a principal did, she reports, “They said, ‘You whip people and make them be good.’ And I told them, ‘No, I don’t need to do that because you’re going to take care of yourselves.’”

School Life, Post-Paddle

Knight Elementary sits among the sprawling, affluent subdivisions that have swallowed up the pastures and dogwood thickets once found throughout Gwinnett County. On the outside, the school is a flat, nondescript brick building, but the inside is an exuberant burst of color. A large red-and-white quilt with a star design adorns the wall by the entrance, and the deep-red-carpeted hallways are plastered with children’s paintings, essays, and posters.

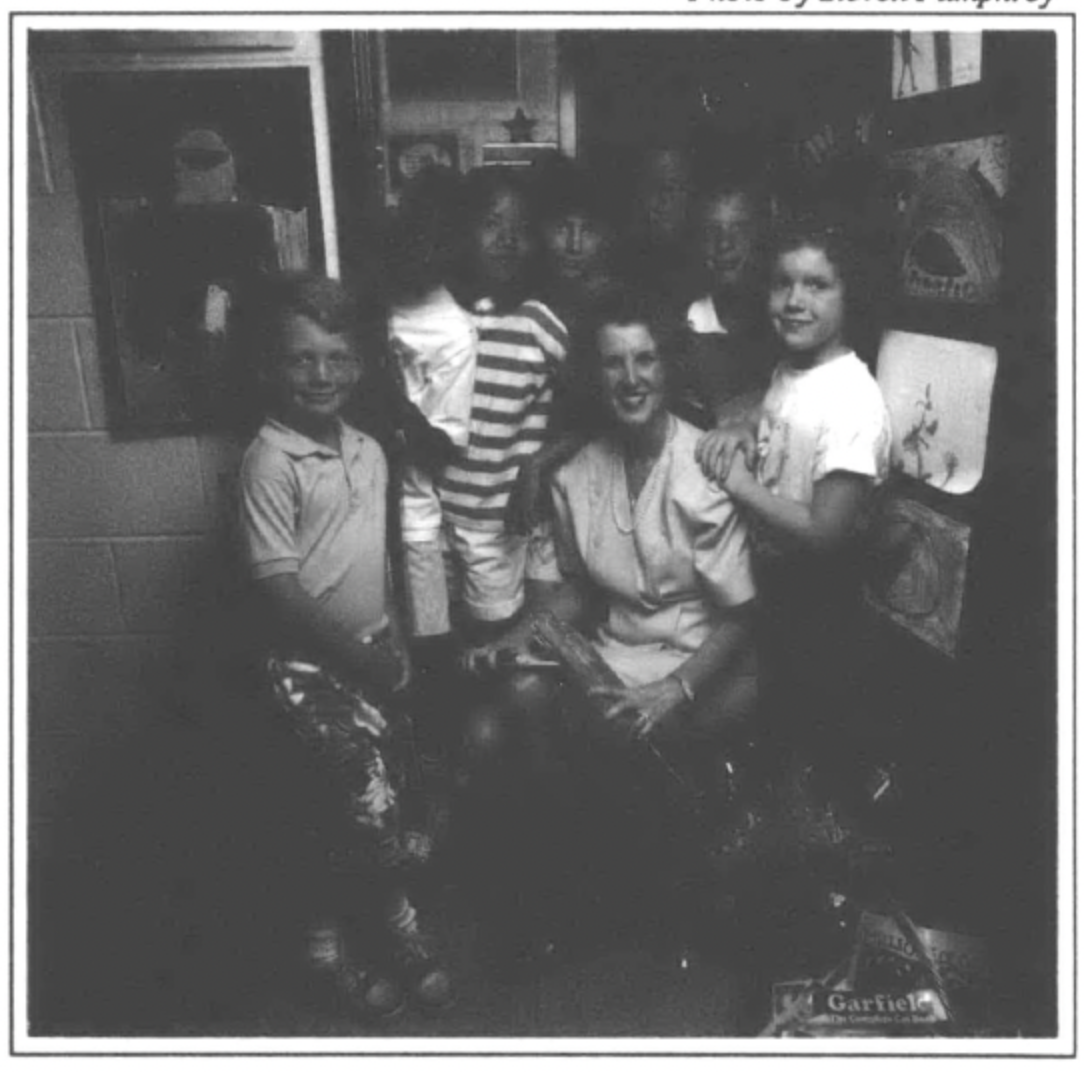

As Meeks talks animatedly about Knight from a table in her office, she offers a striking contrast to the archetypal principal: A tall, slender woman with curly, blond hair and deep-set brown eyes, she is dressed resplendently in a floor-length red dress and red high-heeled shoes.

In the eyes of a young child, Meeks might resemble Glinda, the good witch of the north in The Wizard of Oz, without Glinda’s somewhat saccharine quality. She combines the best of Southern intellectualism (she earned her master’s degree from ‘Ole Miss and a doctorate in early childhood education from the University of Georgia) with humor, warmth, and a respect for children as natural as it is obvious. She intimidates some parents, she says: “I’m tall, and some aren’t used to a woman in this position, which they associate with punishment. But the children aren’t afraid of me at all; they know that I’m going to be fair and consistent.”

Pouring a cup of coffee, Meeks expands on the school’s discipline program, post paddle. Students sent to timeout desks “are usually very repentant and just want to say, ‘I’m sorry,”’ she says. “We tell them, ‘We already know you’re sorry. Now, tell us what you’re going to do about it.’ If a little boy who threw food in the cafeteria says, ‘I’ll keep my hands in my pockets from now on,’ we say, ‘Well, how are you going to eat?’ We may suggest instead that he make a plan to throw a ball or Frisbee outdoors. In any case, we help them think it through.”

Defiance of authority is probably the fastest way to the time-out desk, adds Meeks. “No teacher in the world likes to be talked back to. Usually, it’s some little bitty ones saying, ‘I’m not going to do that work, you can’t make me do it, my daddy said I didn’t have to,’ stuff like that.... And new kids always seem to want to test the system.”

An important goal in Knight’s discipline system is teaching children to negotiate with each other and resolve their own problems. “We’re not advocating that children be wimps or nincompoops,” says Meeks. “We let students know they can face another kid who has hurt them and yell, ‘I’m so mad!’, stomp their feet, and soon. We don’t want kids to see themselves as victims.”

If two students are caught fighting, for example, they must work on their plan together during ‘time-out.’ In one such case, a boy and girl sent to Meeks for fighting on the bus at first refused to even look at each other. “They just sat there glaring,” recalls Meeks, “and I finally pulled their chairs close together and said, ‘Y’all are going to have to talk to each other.’ Well, after a while, they began whispering, ‘Now I tell you what, if you don’t poke your leg out in the aisle where I’ll trip over it, I won’t do this,’ and so on. They were so dear,” she recalls, laughing. “And I said, ‘Fine, let’s try it.’” But the school’s job doesn’t stop there. The teachers, guidance counselor, or Meeks follows up with counseling. As Meeks explains, “We’d ask, ‘Is your plan still working? Do you need to modify it?’ And these two children would say, ‘It’s still working; we’re still doing it.’ They haven’t had a fight since.”

What about kids who break the rules over and over? Not many do, says Meeks, but for repeaters, the first stop after the classroom time-out desk is a desk in the hallway, where students spend 30 minutes writing a plan. A student who continues to break major rules after the hallway time-out, known as the “Opportunity Room,” attends a mammoth counseling session with Meeks, the teacher, the school guidance counselor, and the parents to design a better plan of action. If the parent starts to insult his or her child during a conference, Meeks temporarily halts the session, sending the child to another room while she explains that Knight doesn’t allow any “put-downs” that damage a child’s self-esteem.

On the way to the O.R., as Knight students call it, a large sign on the wall reads: We believe in you. We trust you. We know you can do it! Meeks explains that if students break another rule within six weeks of a counseling session, they receive an in-school suspension, spending a day doing all of their lessons at the hallway desk. Afterward, what many students like best is this: If they don’t break another rule for six weeks, they get to tear up the record of their time in the O.R. Some even make a special ceremony of it, inviting their parents for the occasion.

“I definitely liked the idea of getting rid of the report,” says Kevin Anthony, 10, who went to O.R. only once, for throwing rocks at a tree. “Otherwise, it would just kind of sit there in my mind.” Meeks says that one father has accused her of running a jail, while some parents of “hard-core” kids occasionally ask her to whip their children. (She doesn’t.) But the vast majority are supportive, she reports, and discipline problems at the school—recognized by the White House for academic and overall merit as a National School of Excellence in 1988—have dropped dramatically.

“What I notice the most is the absence of fear and intimidation,” says assistant teacher Philip Ogletree. “From what I can see, the students here are more diplomatic and have more respect for other kids and their teachers.”

Approximately two dozen children interviewed at Knight are unanimous that the discipline program is superior to paddling. Among them is Kevin Anthony, who transferred from a school where he had heard stories of students being paddled. The Knight program “is a good system, not scary,” he says. “It makes you think.” The boy frowns in concentration, searching for the right words. “You feel... you just feel a little safer.”

Vicky Shattles, whose six-year-old son was sent to Meeks after he bit someone on the bus, also praises the discipline system. “My little boy was so afraid to see the principal that he cried all weekend,” she recalls. But Meeks, she says, “was wonderful with him. She told him, ‘Let’s look at what else you can do besides biting when you get angry.’ My son was so excited when he came home that day; he had met the principal and made a wonderful new friend. He hasn’t bitten anybody since.”

A dark-haired woman with a pensive expression, Shattles says that as in every school, Knight has its share of hot-tempered students. But the mere fact that Knight manages to treat them with respect, and without spanking, she says, “encourages all of us as parents to ask ourselves, Do we really need to spank? If Knight can control kids without spanking, can’t we do the same?”

In the Classroom

In the 1980s, a decade in which millions watched New Jersey principal Joe Clark striding through the halls of his urban high school with a baseball bat in hand, Knight Elementary’s biggest challenge to American education was not simply throwing away the paddle. It was replacing punishment with discipline.

To those confused by the difference, child psychiatrist J. Gary May of Denver says the distinction is basically a simple one: Discipline promotes a sense of self-esteem; punishment destroys it. Since punishment is used to cause pain, says May, the child “will often look for ways to ‘pay back’ the individual inflicting the pain—and may do it in a way that is just as cruel, harsh, and uncaring.” Despite numerous studies that support May’s views, most schools still use punishment to control kids. By all accounts, Knight Elementary is one of fewer than 100 large public schools that use the responsibility model of discipline, although the individual teachers using such an approach may number in the thousands. One reason for the paucity of responsibility models is that the approach is relatively new; another is that, as funding cutbacks for public schools result in more overcrowded and sometimes violent classrooms, beleaguered teachers may find it hard to do anything more than just survive. But many teachers in tough urban schools have successfully established “discipline with dignity” programs; in Kansas City, Missouri, inner-city elementary teacher Toby Jean Dickerson says, “People forget that a child anywhere is still a child—a child who wants to please his teacher. And these kids need a place where adults are saying, ‘We believe in you.’”

There’s an old joke that Henry Ford liked to tell: People could select any color of Model T they wanted, as long as it was black. Similarly, most schools offer parents their choice of student discipline—as long as it’s punishment. Many of us are so used to punishment ourselves that it’s difficult to imagine discipline without pain or guilt, without sarcasm or fear. But if schools like Knight Elementary offer any lesson, it’s that students can learn self-discipline.

What’s remarkable about Knight, in fact, is not only how teachers and their students respond to discipline problems, but how few serious discipline problems the school has now. One reason is that from kindergarten on, teachers use role playing to teach children how to solve conflicts with their classmates—without violence. That way, explains kindergarten teacher Dianne Campanelli, children learn how to stand up for themselves at an early age; by doing so, she says, they’ll be better equipped to say ‘no’ later on—and mean it.

In class, she demonstrates what children could say to a classmate dragging them across the yard. Campanelli plays the part of a forlorn student as a small girl pulls her backwards, giggling. “Stop it: We’re playing too rough, and Mrs. Campanelli will make us sit down!” the teacher says firmly, provoking a wave of hilarity from the five-year-olds. (“You are Mrs. Campanelli!” one crows in delight.)

“Now, who else would like to try it?” she asks the students. A sea of hands shoot up in excitement. “Stop it, I already told you I don’t like it when you drag me!” five-year-old Carlos improvises so convincingly that his small captor drops him as if burned, and the two return to their seats, smiling with pride. “That’s good, Carlos,” says Campanelli. “You could even tell him, “And I don’t like it when you don’t listen to me...”

Another reason for Knight’s success is that its classes are small, with an average of 22 students per class. In addition, the school’s teaching style allows for much movement and talking in small groups, taking into account that young children’s attention spans are usually between 10 and 20 minutes. In a second-grade class, teacher Janna Falle nods at a boy preoccupied in writing a mystery story about a missing statue— “a solid-gold pig with diamond eyes... swiped by The Hog.” “You don’t have to worry about discipline when children are absorbed,” Falle explains, noting that she’s only sent two children to a time-out desk all year.

As the debate over school discipline heats up, Meeks says other teachers and principals in Georgia are eager to hear about Knight’s alternative approach. To many educators, this interest is encouraging —and long overdue.

“It’s ironic that the current mood in education—with its emphasis on obedience and punishment—is in some ways behind the past,” concludes educator Richard Curwin, author of Discipline with Dignity. “But we do have hope that the pendulum will once again swing back to the rational position of treating children as people with needs and feelings that are not all that different from our own.”

Meeks agrees. As part of a Georgia coalition that opposes corporal punishment, she frequently gives talks urging school officials to throw away the paddle. “I often tell them the story about the Baptist preacher who sees one of the women in his church beating her son in the front yard,” she says. “He calls out, ‘Mrs. so-and-so, whatever has your son done to deserve such a beating? Is this really going to help?’ And she says, ‘Well, preacher, I don’t remember what he did, but this sure makes me feel better!’... I think it’s time we find a better way.”

Tags

Diana Hembree

Diana Hembree is an award-winning health and science journalist, a former senior editor at Time Inc., and the founding co-editor of MindSiteNews, a nonprofit outlet that covers mental health. She is a native of Georgia.