This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 3, "Sunbelt Blues." Find more from that issue here.

Names of Mexican workers quoted in this story have been changed to protect them from possible reprisals by their employers.

Juarez to Matamoros, Mexico—Federal Highway 2 is the Rio Bravo Highway. It begins in Ciudad Juarez at the northeast corner of Mexico and ends in Matamoros on the Gulf of Mexico. Except for a few hundred miles of Chihuahuan desert, where there is no road, the highway defines the Mexican border. It is also the maquiladora highway, the road that connects the hundreds of foreign-owned assembly plants designed to bring together inexpensive Mexican manual labor and North American capital.

Now in its 24th year, the maquila program is a great success—at least from the standpoint of United States companies. Ford, General Motors, Zenith, General Electric, GTE, and Honeywell have all setup maquiladoras in Mexico. There are now 1,700 plants employing 500,000 Mexicans.

Labor is cheap—“$0.72 U.S. an hour including fringes,” according to a ya’ll come ad that Valcon International, a maquiladora consultant firm, placed in The Wall Street Journal a few years back. And the program allows U.S. manufacturers to circumvent Mexican labor law, particularly a provision that requires reparto de utilidades—profit sharing—among all Mexican employees. Since companies ship in component parts and ship out assembled products, maquiladoras earn no profit; they only incur costs. There is nothing to share. Companies also invest little in employee safety and environmental-protection measures, and face no private tort system by which workers can go to court to collect damages for death or injury on the job.

Newsweek has described the maquiladoras as “sweatshops along the border,” where “even by Mexico’s own dismal standards, most U.S. maquiladora operators are exploiting their workers.” Yet Mexicans continue to flock to the maquilas, and all along the road from Juarez to Matamoros, there is evidence that the plants have started a demographic revolution that has changed the character of the border region.

From Field to Factory

The most visible sign of this demographic revolution are the colonias scattered along the federal highway between Reynosa and Matamoros in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Most are squatter towns, where new arrivals have settled in and claimed tiny plots of land as “posesiones”—by the constitutional right of occupation. With names like El Popular, La Roma, 1 de Mayo, and Solidaridad, all the colonias share certain characteristics. There is no potable water, no sanitary sewers, no paved streets, no electricity, and few men. Each community is sustained by women—women between 16 and 25 years of age. “There is not a single man working on my shift,” a 19-year-old from Electronic Control Data said. Many men, frustrated with the low pay or unable to find work in the maquilas, cross the river into the United States.

Seventy-five percent of maquiladora employees are women, and a day spent on the streets and around the kitchen tables of half a dozen Valley colonias reveals that most share a common background. “Ask the same question 15 times, you’ll get the same answer 15 times,” said a labor organizer who requested to remain anonymous. From La Roma in Reynosa, to El Popular in Rio Bravo, to 1 de Mayo in Brownsville, the response to the question, “Where are you from?” is so similar that it is almost disturbing. “Pues, de un ranchito...” (Well, from a little ranch). Whether from the state of Vera Cruz or nearby Nuevo Leon, all of these women are from rural Mexico. “This is their first real experience with an industrial society,” the labor organizer said.

The family of Maria de Rosario Escamilla is typical of many in the colonias. Senora Escamilla, in her late forties, followed her daughters up from a small rural village in the state of Vera Cruz, where the family still owns a home and a parcel of land. In Vera Cruz, she said, life was better. “We had a large house with a porch, with shade and fruit trees, chickens, cows, pigs.... There was everything except work. Here we have this,” she said, pointing to the dirt floor in her kitchen.

In Reynosa, the Escamilla family lives in a 250-square-foot cinder-block house. The roof is made of corrugated tar paper and neither glass nor screen covers the windows. Two years ago the entire colonia was a shallow lagoon that filled up after every rain, Senora Escamilla said. On this particular day, one week after a heavy downpour, the house was an island, built on an elevated base of masonry scrap and surrounded by water. A nearby community outhouse was almost completely submerged.

The Escamilla family lives on the earnings of two daughters, 18 and 19 years old. Each daughter works at a different Delnosa plant assembling components for GM cars. They earn the same amount: 84,700 pesos ($29.40 U.S.) for a six-day, 48-hour week. After bus fare is deducted, $ 100 U.S. a month is all that remains of each paycheck.

The lowest rents in Reynosa are around 100,000 pesos a room ($35 U.S.)—beyond the reach of the Escamilla family. They could never afford both rent and food, Senora Escamilla said. (An hour of work at Delnosa, for example, buys less than a kilo of flour, or a half kilo of chicken, or one package of toilet tissue. It takes three hours to earn enough to buy a 980-milliliter bottle of shampoo.) So the family avoids the cost of rent by living in a squatter’s colonia.

“I tell my husband that when both girls marry, we ’U go back to Vera Cruz where we can die in peace,” she said. It’s unlikely that they’ll return. Already Senora Escamilla’s parents, two brothers, and three married children have followed her to Reynosa. All live in the same colonia. Senor Escamilla, a mason, is only able to find occasional work, and his wife worries that their daughters will move to Matamoros, where the pay in the maquiladoras is slightly higher.

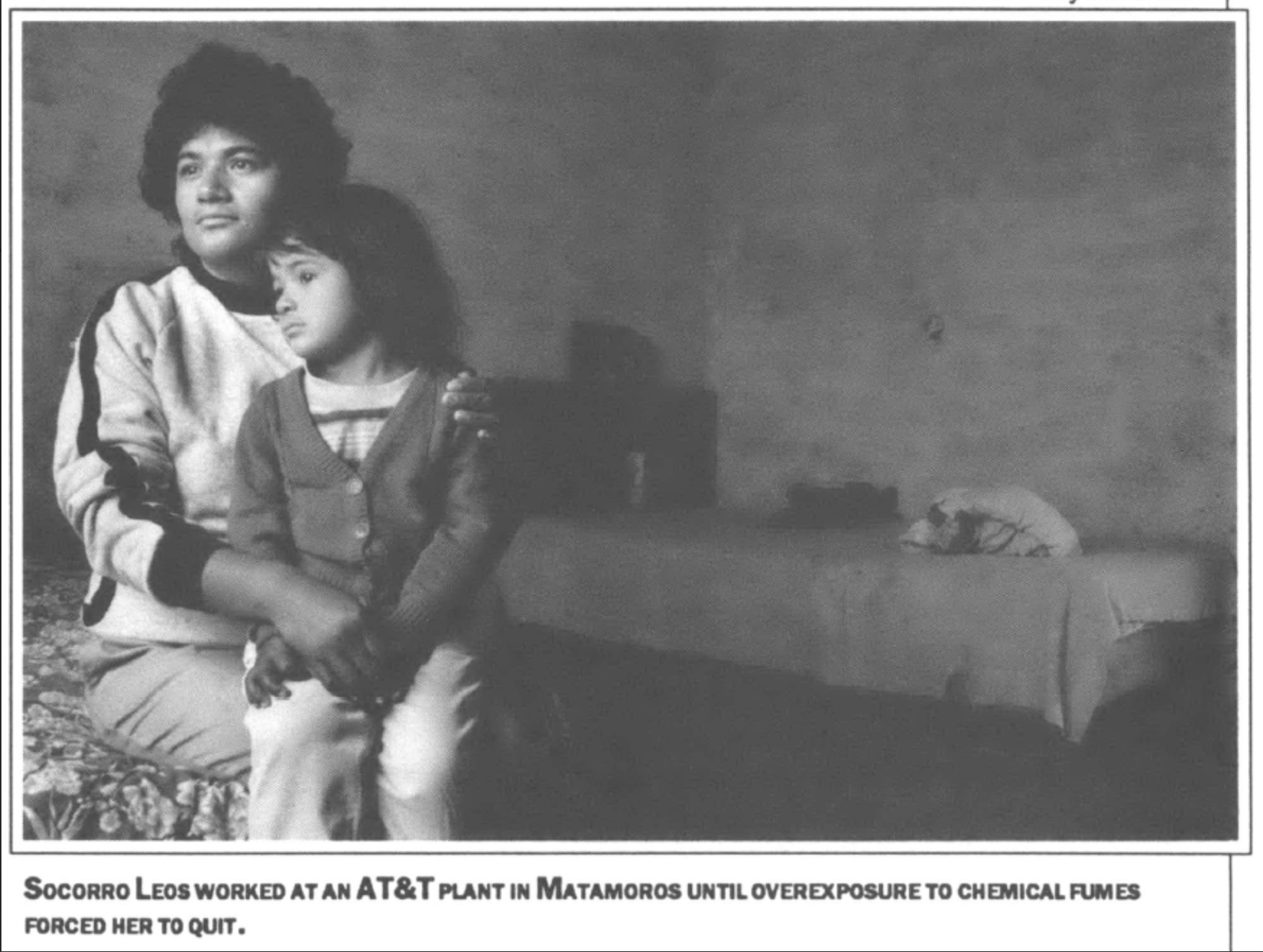

Three houses from the Escamillas, a family of 12 lives in a 350-square-foothouse of scrap wood and tin, and a white pressboard 12-by-12 sleeping hut built by an organization called World Servant-Europe. “Five of us were working, now only three,” a young woman seated outside the house said. Two sisters, both under 20, had recently quit their jobs at maquiladoras. One left Parker Hannifan, where she had been an inspector. After seven months of staring through a brightly lit magnifying loop, looking for defects in seals, her eyes became so irritated that she could no longer work, she said. She had started at 65,000 pesos a week (47 cents an hour) and was earning 71,000 pesos (51 cents an hour) when she resigned.

Her older sister had left Erika, where she assembled I.V. bags for use in U.S. hospitals. The solvents used in the plant bothered her. Ventilation was poor, and on one occasion when she became faint and nauseated, she was sent to the infirmary. “They gave me an injection and a pill and told me to rest for a while and then go back to work,” she said.

After almost a year on the night shift, she quit to look for a day job in a place where the fumes aren’t so bad. The salary she gave up was 92,000 pesos ($31 U.S.) for a 48-hour week. A brother, who was asleep in a neighbor’s house, works the night shift at Calzada Deportiva de Reynosa, manufacturing Converse athletic shoes. The family had moved to Reynosa a year ago from a tiny village in Nuevo Leon.

Jobs and Dollars

At the other end of the maquiladora highway stands Juarez, the center of the burgeoning industry. Located across the Rio Grande from El Paso, the city is home to 300 maquilas that employ nearly a third of all maquila workers in Mexico.

Like the colonias that dot the highway, Juarez is a city in chaos. Many of its estimated 1.2 million residents live in squalor, often without sewage facilities, electricity, and water. Housing is in short supply, forcing thousands to live in shacks. Transportation is bad, and roads in many neighborhoods are mere drainage ditches.

The Bermudez Industrial Park is a bit of suburbia in the midst of this dire poverty. Perfectly coiffured green lawns encircle warehouse-style factories on tree-lined streets that host the largest concentration of U.S. companies in Mexico.

Driving along the manicured streets, it’s not hard to see why the Mexican government has welcomed the maquiladoras with open arms. In a poor country with rampant unemployment, U.S. companies mean jobs and dollars. Last year the industry flooded Mexico with $3.1 billion in foreign currency; only oil earned more.

The maquiladora program dates back to the mid-1960s, when Mexican workers who had been imported during the labor shortages of World War II were sent home. Mexican border towns could not absorb the flood of returning workers. Faced with soaring unemployment, the Mexican government established the Border Industrial Program.

Designed as a stop-gap measure, the program allowed foreign subsidiaries to set up maquiladoras in Mexico to take advantage of low labor costs and unregulated investment. The United States, for its part, cut tariffs and duties for firms that opened plants along the border.

As the Mexican government grew to depend on the maquilas for foreign currency and employment, it expanded the program and further loosened government regulations on the industry. Today maquilas employ everyone from garment workers to coupon sorters, but the largest sectors of the industry are transportation and electronics. Parts for all of the Big Three auto manufacturers are assembled in the maquiladoras, as are circuit boards and other electronic equipment.

U.S. business leaders like to brag that they have modernized the Mexican workforce. “I was there when the maquilas began,” said Bill Mitchell, a maquiladora consultant. “The people were farmers. They didn’t know what a screwdriver was. They had never seen the inside of a factory. Now look at them. They’re a very sophisticated and industrialized people.”

“Different Needs”

Boosters of the maquiladora program on both sides of the border insist that the industry provides enough to live on—at least, enough for a Mexican to live on. “It’s certainly not a livable wage as we would describe it, but they're living on it,” said Don Shuffstall, a maquiladora consultant for U.S. companies and president of Border-Trax, a maquila publication.

Mexican officials also seem proud that maquiladora wages are so low. “You should not compare Mexican wages to American wages, but rather compare them to wages in Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, the Philippines, or Singapore,” said Roberto Gamboa, the Mexican Counsel General in El Paso. “Those are the countries we are competing against.”

Gamboa painted a picture of Mexicans willing to do without. “The wages are always in accordance to the cost of life, and the cost of life is much, much less and the needs of a Mexican family are different than the needs of an American family,” he said. “We may be satisfied with less than the Americans.”

Critics argue, however, that giant corporations have a responsibility to pay a decent wage. “These aren’t a bunch of fly-by-night operations that are barely eeking out a profit on the backs of the poor,” said Victor Munoz of the AFLCIO in El Paso. “These are Fortune 500 corporations that generate millions in profits and have a responsibility to give something back to the communities where they are located. How can they get away with paying workers $32 a week? That is a crime.”

In some ways, the low wages backfire on companies. Turnover at the maquiladoras can run as high as 30 percent a month; at that rate, a plant would have to replace its entire workforce twice a year. At nearly every maquila plant in Juarez, huge billboards advertise for workers.

So far, though, no manufacturer has dared to increase wages to keep workers on the job. After all, a bidding war by employers would defeat the whole concept of the maquiladoras. “A firm would be castigated for breaking the wage scale,” says Jeffery Brannon, an economist at the University of Texas in El Paso.

In border towns like El Paso, elected officials are betting their futures on the maquiladora industry. “The leaders in this community have gone overboard in promoting the maquilas as a last chance for the U.S. border areas,” said Brannon.

Earlier this year, El Paso Mayor Suzie Azar kicked off a conference held to salute the industry by proclaiming the city “maquila capital of the world.” Azar co-owns a maquila plant across the border in Juarez.

Don Shuffstall, the maquila consultant, estimates that at least 30,000 people in El Paso owe their jobs to the maquilas in Mexico. “The growth of El Paso would have been probably zero this past 10 years had it not been for what’s going on over there,” he said.

But much of the growth in El Paso has been in the warehouse district, which has done little to revive the city’s faltering economy. Unemployment has remained at just under 10 percent over the last several years, and the per capita income has stagnated. Brannon, the University of Texas economist, also points to the hidden costs of the maquilas. Pollution, congestion, water shortages, and immigration problems along the border are all intensified by the maquiladoras.

“Maquiladora is promoted as the greatest thing since orange juice, but who benefits from this?” Brannon said. “If our city and our Chamber of Commerce are spending local dollars to promote that industry in Juarez, one has to ask: Are the benefits widespread, or are they being captured by a handful of people?”

Opening Doors

The question of who benefits has not gone unasked along the maquiladora highway. In the colonias around Reynosa and Matamoros, there is evidence that the families who have moved north to work in the maquilas are part of something more than a demographic revolution. Ten years of quiet and persistent organizing have resulted in some real change inside the factories.

The movement began outside the official unions of the Confederacion de Trabajadores Mexicanos when several comites de obreras—worker’s committees—organized with the backing of the Mexican and American Friends Service Committees. What started with a few small gatherings in private homes has now spread across the region and includes a regional worker’s committee and a binational Grupo de Apoyo—a support group made up of teachers, lawyers, and professors from both sides of the border.

The committee scored an initial success by opening a few doors in 1980. “The first victory,” one woman said, “was in Rey-Mex,” a company that manufactures bras for Sears. According to one worker, the Rey-Mex factory in Reynosa was a firetrap. The motors of the old sewing machines sometimes sparked, igniting pieces of cloth. And there was only one exit. “There were other doors,” a worker said, “but they were chained shut with rusty padlocks that no one could open.” The committee pressured its union delegate to take their demand to management, and the padlocks were removed.

Another victory came five years later, when the comite de obreras won a 50-percent pay increase from Electronic Control Data. It was done, according to a source in the plant, by gradually organizing an entire shift and then going to the union delegate.

“At first, only a few went into the delegate’s office,” a worker said. “And we were dismissed.” The entire shift then marched on the office, surrounding the delegate’s desk and spilling into the hallway. Many were surprised when they won the raise. Unions are an official sector of the government in Mexico and tend to be controlled by the ruling party, which strongly supports the maquiladora program.

Other successes have been more modest. In Rio Bravo a woman told of a “sociodrama” at a meeting on the patio of her home. Some 40 workers watched as two others acted out the roles of a supervisor confronted by a worker whose pay envelope was short 5,000 pesos. Most of the maquiladoras pay in cash, stapled to a pay stub that lists deductions. In the drama the worker had to persist, look the supervisor in the eye, and demand the missing money. The workers were told never to unstaple money until they count it, and not to leave the factory until any missing money is handed over. Three days after the drama, the woman’s daughter, a Zenith employee, was shorted 3,000 pesos. “She went to three or four offices, but she got her money,” the woman said.

At the small group meetings, worker leaders discuss labor law, workers’ rights, and even body language. At some gatherings workers from one city meet with workers from another—often to share success stories. A common tactic is to hand out photocopies of pay receipts from a company that operates similar plants in different towns. Often pay differs considerably for workers with the same job and seniority. One page of photocopied receipts showed that workers at a Zenith plant in Matamoros earned 49,510 pesos less than Zenith employees doing the same job at the same number of hours at a plant in Reynosa. “That was the leaven to start the discussion,” a woman on the committee said.

Ana Maria Valdez, a fulltime organizer who once worked at Union Carbide in Matamoros, said that the plant was completely reorganized after several women wrote to Audrey Smock of the United Church of Christ in New York and informed her that they were required to clean with methylene chloride. “We washed our hands with it. If we got epoxy on our blouse, we washed the spot with it,” Valdez said. “Workers complained of rashes, respiratory problems, and liver and kidney ailments.” Smock went to Union Carbide headquarters in New York and reported how methylene chloride was being used in Mexico. Within weeks, a team of inspectors arrived from New York. Individual ventilators, gloves, glasses, and protective clothing have made such a difference that comite de obreras members now consider the plant—now called Kemet de Mexico—a model for change. Valdez said the improvements at Union Carbide were brought about despite the official union. The committees have created a space between management and organized labor—and in that space they a reteaching a generation of women something about empowerment. “We might be trembling, but we look them in the eye,” Valdez said. “We’re humble, but we’re not on our knees anymore.

Tags

Louis Dubose

Lou Dubose is editor of The Texas Observer, and Ellen Hosmer is editor-at-large of Multinational Monitor. Names of Mexican workers quoted in this story have been changed to protect them from possible reprisals by their employers. (1990)

Ellen Hosmer

Lou Dubose is editor of The Texas Observer, and Ellen Hosmer is editor-at-large of Multinational Monitor. Names of Mexican workers quoted in this story have been changed to protect them from possible reprisals by their employers. (1990)