This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 2, "Birth Rights." Find more from that issue here.

Cheryl Bostic, a grassroots organizer in Atlanta who reminds me of a powerful Amazon warrior, challenged me to tell it like it is. “African-American writers need to start writing the truth,” she said.

And because I believe that she is what all African-American women must become — practical visionaries — I will write the truth. My truth.

My truth being how difficult it is for African-American women working in reproductive rights organizations to move away from “the issues” and bring it home to our personal truths. How the realities of class and religion still present fiery barriers to unity with white women on an issue of survival. How hard it is, years later, to recall the pain and fear of a backroom abortion in a small, Southern town. . .

On April 9, 1989, more than 300,000 people converged on the White House in what has been called the largest women’s rights march in history. On that day, feminists, lesbians, grandmothers, flight attendants, and movie stars stood shoulder to shoulder, demanding full reproductive rights for all women.

It was a landmark day — but it did not take a pollster to see that something was missing. The sea of women that washed over the city was overwhelmingly white and middle class. Where were the women of color?

Many in the news media wondered about this “no-show” status. Perhaps, some suggested, black women stayed away because they oppose legalized abortion. As Newsweek concluded, “Some leaders doubt that blacks will ever become pro-choice activists in large numbers.” Or perhaps, others said, black women simply have no position on the issue.

But I had a position and I wasn’t there. While I was in high school, cradled in the lap of a middle-class Southern black family, I had an illegal abortion.

I was 16 and two months pregnant. My mother made the decision, and I endorsed it by climbing on top of a table in the basement of a house in Reidsville, North Carolina. It was a pretty house with flowers and a white picket fence.

The woman who lived there inserted a rubber, coiled, snake-like instrument into my body. It didn’t hurt until later. Then the pain was excruciating. I was delirious. My grandmother gave me castor oil and a laxative called Black Draught and sat with me for two days until the placenta came out. She never left my side.

The memory of that day haunted me for years in a nightmare of that snake-like instrument, but I continued to feel that no one had the right to withhold that choice from me then . . . or now.

Yet I was not at the march on Washington last April. I was among the tens of thousands of black women who stayed home, kept quiet, despite our support for reproductive rights. So as I set out to ask other African-American women, “Why weren’t you there?” I asked myself that same question.

Statistics and Survival

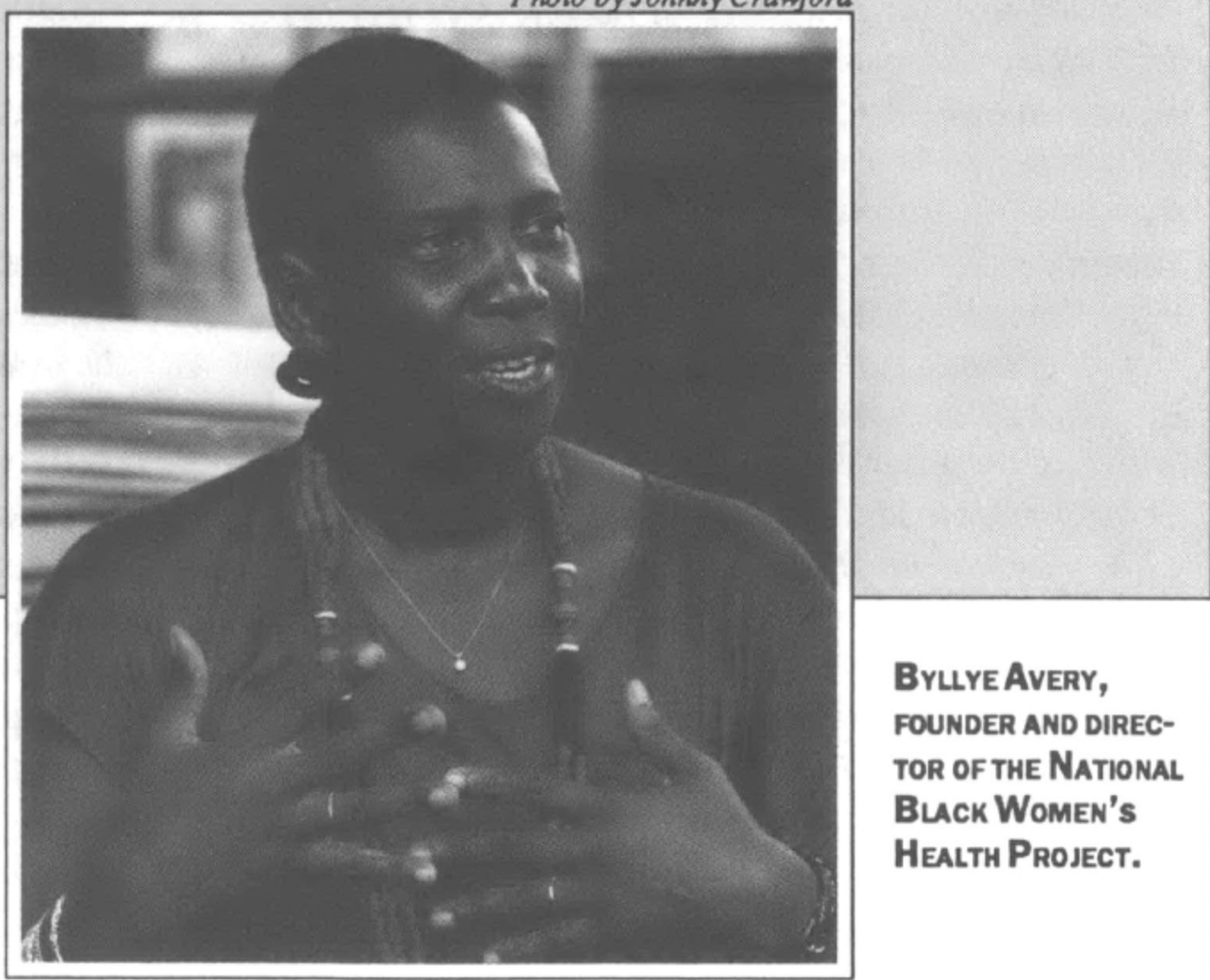

Naima Major was there that day. The development director of the Black Women’s Health Project in Atlanta, Major cautions against overlooking the many black women who struggle for reproductive rights every day.

“The media ignored the presence of those of us who were there,” she says. “For instance, reporters failed to note that this was the largest gathering of black women in any abortion rights march. Each one of us represented at least a hundred African-American women who couldn’t be there. And not one of the journalists mentioned the African-American men marching — with their families.”

Nevertheless, Major and other women at the Health Project concede that the reproductive rights movement remains primarily white and middle class. “Where black women are — mentally, physically, and emotionally — on the issue of reproductive rights is not a new question,” says Loretta Ross, program director at the project. “The reason it still lingers unanswered is it has not been adequately addressed.”

Ultimately, the answer to the question depends on how the question is asked. White women ask, “Why aren’t more black women involved in the movement?” Black women ask, “Why doesn’t the movement involve more black women?”

No one disputes the need to involve more women of color, but many fail to realize that any genuine effort to expand African-American participation will have to take into account the reality of our everyday lives. Most black women have not read the statistics on abortion — they have lived them.

According to recent studies, about three percent of American women aged 15 to 44 end unwanted pregnancy in abortion. Of those, minority women are more than twice as likely as white women to have an abortion. The figures also show that nearly half of all black females become pregnant as teenagers — 90 percent of them while they are unmarried.

Black women know the reality of giving birth and raising families, but many know little about the issue of reproductive rights. Mention the name Webster and a black woman will more likely think of the short, wise-cracking black kid of the television series than the Supreme Court decision that opened the door to state restrictions on abortion rights.

For these women, every waking thought involves the survival of their families — for food, clothing, and shelter. Most often, when they contemplate abortion, it is a choice they face out of desperation, out of concern for the living.

Contrary to any stereotype, an abortion has never been a decision of convenience for most black women. The death of a fetus never takes place without our guilt, shame, and emotional upheaval, especially confronted as we are with the very survival of our race. We have not forgotten the days when abortion was illegal, and those memories have forced us into a conspiracy of silence. Abortion is seldom discussed in our communities, even among families who know a relative or neighbor who has had an abortion.

Carolyn’s Story

One day I ask Carolyn, a 40-year-old nurse I know, if she knows anyone who

almost died as a result of an illegal abortion. She pauses, and then sighs deeply, lost in thought. Her long silence is finally broken by a whisper. “If you don’t use my name,” she says, “I’ll tell you my story.”

Then she begins to sob, her words ripping from her soul like a torn piece of flesh, still painful after 22 years.

At 18, Carolyn was living with her husband and their first child when she discovered she was pregnant again. Her husband was a college student, born to a mother of seven on welfare, and he believed deeply that his only escape from poverty was through education. He and Carolyn decided they could not afford another child — not yet.

Together, through the underground abortion railroad, they found someone in a neighboring town who was willing to perform the illegal procedure. Carolyn permitted her uterus to be punctured by an alien wire, which left her hemorrhaging. Terrified, she got medical attention at a local hospital. When the doctor questioned her, she lied about what happened.

Carolyn survived the ordeal physically, but to this day she and her husband have never talked about the trauma. Consequently she considers the abortion “a sinful murder,” one that is still hemorrhaging, one that has left her convinced that abortion is not the answer to unwanted pregnancies.

Yet as a nurse, witnessing the lack of health care black women receive when they give birth, Carolyn cannot say she would like the option of legal abortions to be taken away. She supports giving women a choice, but she cannot bring herself to say it . . . not out loud.

Silence and Damnation

This painful conspiracy of silence pervades the black community, stifling our voices, denying us the shared wisdom of our own experiences. “How can a silent community be a committed one?” asks Loretta Ross at the Black Women’s Health Project.

Many women active in the reproductive rights movement blame the black church for playing a conspiratorial role in promoting this silence. Denouncing abortion even when it was illegal, black ministers preached warnings of hell and brimstone from their pulpits while member after member of their congregations — often members of their own immediate families — sought abortions in the still of the night. Now, in the era of legal abortion, the church continues its warnings of eternal damnation, laying the burden of sin at the feet of its poorest parishioners.

“The black church played a major conspiratorial role in women’s silence,” says Lillie Allen, a pro-choice activist who provides leadership training for women’s groups.

Allen and other black activists point out, however, that the church gave birth to the civil rights movement, and it should be at the forefront once again in the struggle for freedom of choice.

Black Pain, White Agendas

With or without the church, black activists say they will continue to fight for their human rights — including their reproductive rights. But the question remains: How can we break our silence and join ranks with white women in the struggle for freedom of choice?

Part of the answer lies in the success of the civil rights movement, which brought blacks and whites together in the ’60s. Brownie Ledbetter, a white civil rights activist in Arkansas who founded the first Planned Parenthood chapter in Little Rock, says whites need to work harder to understand the reality facing blacks.

“Inherent in the problem today is that younger women don’t know about each other’s history,” Ledbetter says. “Many white women come into the prochoice movement out of their own reactions and may not see the unique pains of black women.”

Ledbetter adds that white women need to “be aware of how black women and men have been treated in this country. Prejudice is a disease — you have to recognize it to be effective in changing anything.”

Many black women echo Ledbetter’s sentiments. “The bottom line for many Americans is they don’t feel good about sexually active women,” says Naima Majors of the Women’s Health Project. “Most white Americans’ response to pregnancy for women of color is: ‘You don’t need to have any children.’”

African-American activists also say they sometimes feel that white women who invite them to join multi-racial coalitions have already set the agenda and handpicked the leaders.

In 1985, for example, the Religious Coalition for Abortion Rights established a Women of Color Partnership Program to involve more minorities in the reproductive rights movement. Many black organizers were outraged, however, saying the coalition should have funded an existing black organization to set an agenda and select leaders.

“Don’t invite us to join your agenda — support us to find an agenda of our own,” says Cheryl Boykins, director of a self-help group called the Wellness Center in Atlanta. “Help us fight for quality lives for ourselves and all our children.”

But unity is a two-way street, and black women themselves will have to struggle with their own prejudices and insecurities. Lillie Allen, who leads training workshops for women, says black women must learn to be “present” — to deal with their fears and sense of powerlessness until they can feel secure.

If black women want more respect and understanding, they will also have to be more accepting of who white women are. An African-American friend of mine who attended a national women’s conference, for example, was enjoying the interaction with white activists until the last day of the conference. During the final session, women who were living “alternative lifestyles” were asked to stand.

“I was shocked,” my friend said. “Myself and three other people were the only ones who didn’t stand up. After that, I was afraid and I wanted to leave.” She left the conference immediately, refusing to attend a going-away party with the very women with whom she had bonded for the past three days.

In the end, however, personal differences may not be as big an obstacle to coalition-building as the way the issue is framed. Above all, black activists stress that whites who genuinely want to work with them must place abortion and reproductive rights in a wider context — a context that addresses the reality of black lives.

“White organizations will have to offer broader issues that directly affect us, and then offer position statements that are relevant,” says Brenda Williamson, former director of the North Carolina Religious Coalition for Abortion. “Those issues must demand more than the right to abortion. They must demand the right of a woman to have a healthy baby if she chooses, a decent job, and a good education.”

Tags

Evelyn Coleman

Evelyn Coleman, a mother of two grown women, is a freelance writer living in Atlanta. (1990)