This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 2, "Birth Rights." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

Atlanta, Ga. — Every evening when Lynne Randall returns home from work, she immediately looks for her cats. And when she goes to sleep at night, she is haunted by recurring nightmares.

“I fear for my safety a lot,” says the director of the Feminist Women’s Health Center. “They all know who I am. It’s not like I have any opportunity for anonymity. When people get up in your face and tell you they wish you were dead, that they are praying for your death, it’s hard not to be shaken up at times.”

Since 1988, when the Democratic National Convention was held here, Randall’s clinic has been the target of constant harassment by Operation Rescue, the nation’s most visible and virulent antiabortion organization. The clinic has been the scene of violent protests designed to physically bar women from entering, and its workers have been subjected to repeated terrorist tactics.

One clinic employee who was followed home by antichoice activists emerged for work the next morning to find two dead kittens on her front porch with a note attached. “Try killing something besides babies,” the scrawled message said.

A clinic doctor who left Atlanta for a weekend getaway was followed for 200 miles by anti-choice vigilantes. Doctors now have to be driven to and from the clinic by workers so protesters cannot vandalize their cars and trace their license numbers.

Another clinic worker who was pregnant took her maternity leave three months early because the constant threats and jostling from protesters made her fear a miscarriage.

“They always deliver the death threats to the women’s families, to their husbands instead of directly to them,” Randall explains. “It’s very intentional, to upset their husbands so their families will put pressure on them to quit.”

In addition to the routine harassment of doctors and other staff, the clinic was the object of anti-choice protests 18 of the 27 days it was open in March. Protesters follow workers to their cars and pursue them to their homes, where they continue to harass the women and their families. Several local governments have passed ordinances banning such tactics.

“It’s been pretty devastating,” Randall continues. “We’ve done a remarkable job of holding ourselves together, but it certainly has caused a lot of stress on our employees and their families. We had a psychologist coming in for group counseling sessions. We’ve done a number of different things to deal with the stress, but it has caused a number of people to quit.”

From New Orleans to Norfolk, abortion clinics all over the South have come under siege. In cities large and small, these facilities have been assaulted by protesters determined to harass their staff and patients and prevent women from receiving health care. Worst of all, scores of clinics have been the targets of violent attacks — bombings, vandalism, and arson — that have destroyed millions of dollars in property and created a climate of fear and intimidation not unlike the racial terror provoked by the Ku Klux Klan.

According to law enforcement authorities, clinics have been the targets of eight bombings, 28 arsons, 28 attempted bombings or arsons, and 170 acts of vandalism. Some of the most violent attacks have taken place in the South. Clinics like the Feminist Women’s Health Center have been chosen as particular targets by anti-choice demonstrators, who flock from the surrounding region with the express purpose of keeping the clinics from delivering health care to women.

“The clinics are really a symbol of women’s sexuality,” says Randall. “You can’t go out on the street and ask who is sexually active and target those women. But you know when women are coming into our clinic, they are seeking some type of reproductive health care, whether it is abortion or birth control or pregnancy tests. The protesters see these women as evil. I’ve always felt that they may not like abortion, but they really hate feminism.”

No Keys Needed

For Kathy Olsen, former director of the All Women’s Health Center in Ocala, Florida, the worst nightmare became real —not just once but twice in a month. One night last year she was roused from sleep at 2 a.m. by a call from police, who had been summoned by the clinic’s alarm. She grabbed her keys and headed for the clinic, believing the alarm had gone off by mistake — but she discovered that no keys were necessary to get inside.

The entire back of the building had been blown open by an explosion from a firebomb. Smoke had poured through the building and the intensity of the heat had melted all the light fixtures.

“You just never thought it would ever really happen,” Olsen says. “It was like a violation.”

After rerouting 25 clients scheduled for appointments that day, Olsen and her staff began the task of cleaning up the clinic and restoring it to operational order. Salvaging what they could from the heat and smoke, they managed to get the clinic back in business within a few weeks. Then came the second firebomb.

“That was when they burned us completely to the ground,” she recalls. “Then, I was really scared.”

After the second bombing, the site was abandoned and the clinic moved to a more secure location in a nearby shopping center. Olsen has since moved to Gainesville to work in a clinic there. No suspect has been arrested for the bombings.

Three-Month Siege

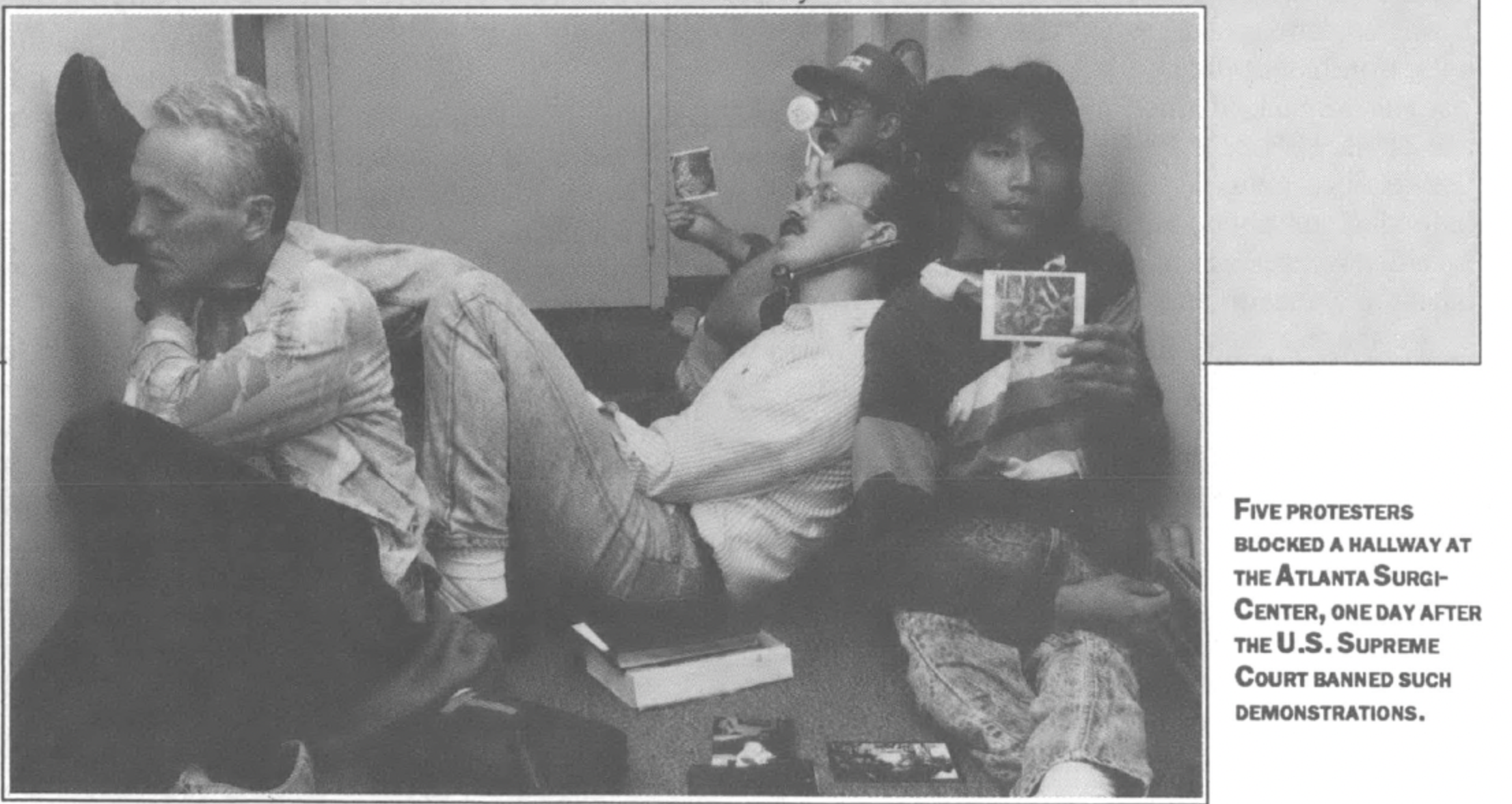

For some clinics, the protests have become so common, they seem almost routine. “I drive up to the clinic every morning and wonder what I’m going to find,” shrugs Beth Petzelt, the lanky sophisticate who directs the staff of the Atlanta Surgi-Center, another favorite target of Operation Rescue. “The worst is when they get into the clinic. It’s a real violation for us.”

On several occasions, anti-choice protesters have posed as would-be clients to get into the waiting rooms at both the Surgi-Center and the Feminist Clinic. Once inside, they harass the real patients, screaming abusive remarks and calling them “baby killers.”

But there is little to compare with the assault on Atlanta clinics staged by Operation Rescue during the Democratic National Convention in July 1988. More than 1,200 protesters were arrested during the three-month siege, clogging Atlanta jails and costing the city millions of dollars. According to Atlanta public safety officials, just one week of police presence at the protests in October cost more than $100,000 — not including detention and court costs for those arrested.

Many of those arrested refused to give their names, which meant they remained in the city jail for weeks or even months. Despite a permanent injunction banning the protesters from coming within 50 feet of clinic property, the arrests have continued.

On more than one occasion, Petzelt has arrived at the Surgi-Center to find some type of vandalism — glass doors shattered by bricks, graffiti scrawled on the outer walls, her locks epoxied shut.

The Atlanta demonstrations soon spread across the region. “Sometimes fights have broken out among demonstrators and they yell so loud you can hear them inside the building,” says Kathleen O’Donohue, director of the Women’s Community Health Center in Huntsville, Alabama. “They tell lies — things like the clinic has no real doctor, that the staff isn’t licensed, that the patients are going to die. There has been some vandalism, throwing of eggs, paint, tarred locks. And they have slashed tires and damaged vehicles. Bomb threats were regular events — we got at least a half-dozen of them.”

In many cities, the siege has actually helped to foster a sense of camaraderie among clinics. In Atlanta last year, the health centers formed an association to wage a legal battle for reproductive rights and assist each other in times of stress. “In a backhanded way, the Operation Rescue picketing of Atlanta was the best thing that ever happened to choice,” says Kathy Collumb of the Georgia Abortion Rights Action League (GARAL). “The clinics weren’t activists. They would support a woman’s right to choose, but they were very passive about it. What happened with Operation Rescue and the television and newspaper reports shook a lot of people up. It got a lot of people angry. At that point, GARAL was deluged with calls from people who wanted to help.”

Freaked Out

One way that people offered to help was to volunteer to escort patients into the clinics. Organized and trained by GARAL during the 1988 Operation Rescue assault, the escorts continue to move dozens of women through the gauntlet of threats, epithets, and intimidation every week.

“The patients are freaked out,” explains Collumb, who trains the escorts. “No matter how clear and centered and focused they are on their decision to have this procedure, it’s very, very scary for a woman to be confronted by these hordes of protesters.

“I have a counseling background,” she continues. “I have worked in abortion facilities before and I know what some of the psychic stresses are on women in this whole process. A woman having to go through a group of anti-choice picketers is subjected to an emotional rape in terms of how it impacts on her, in terms of the vio-

lation of her privacy, in terms of taking something away from her by force. That is basically what the protesters do, the more aggressive and hostile ones.”

The strategy is simple. Escorts — trained not to interact with the protesters in any way — surround the patient and shield her from physical and verbal abuse. One person is assigned specifically to touch and talk gently to the patient as she makes her way into the clinic. If she is accompanied, another escort team is assigned to her partner to diminish the chance for confrontation.

“Every time we are successful in getting a patient into the clinic, it escalates the protesters,” Collumb says. “It just shows them they have failed. You can walk 20 feet and it feels like 200 yards. They call us ‘death-scorts.’ They bait us. They try to engage us in arguments. Their tactics are just slimy, in my opinion. They will write down the license plates from the cars so they can call the woman up at home and try to harass her even after the abortion.”

In the two years the escort program has been operating, no confrontations have occurred between an escort and a protester. GARAL has trained more than 300 escorts and provides the service weekly to the Feminist Women’s Health Center and the Atlanta Surgi-Center, the two clinics most often attacked by protesters.

Closing Ranks

After the Operation Rescue harassment began, local clinics formed cooperative agreements to take patients turned away from other clinics by the protests. They also organized to defeat a flurry of anti-choice bills in the 1990 session of the Georgia legislature, and organizers say individual contributions to GARAL, the Feminist Women’s Health Center, and other pro-choice organizations are up.

But the protests have caused other types of financial problems. Corporate funding for Planned Parenthood and other actively pro-choice organizations is in jeopardy, reportedly targeted by the antichoice network for pressure, threatened boycotts and lobbying campaigns. (See sidebar.)

Keeping the Feminist clinic open throughout the protests has been so demanding, Randall says, that new programs have been put on hold indefinitely. An AIDS prevention project, for example, lost its government grant and has been postponed because Randall has had no time to look for other grants or corporate sponsors.

To top it off, the clinic had its insurance canceled. “Nobody would say specifically it was because of the anti-abortion activity,” Randall explains, “but everybody knows it is.”

First, the clinic lost its property insurance. Then, its liability insurance was canceled. “Our insurance agent feels certain it was because of the presence and the exposure of the antis, that people were going to be pushed and shoved and there was more likelihood that somebody would fall down and sue.”

Nor has Operation Rescue limited its intimidation to the clinics. Fulton County Solicitor Lee O’Brian has endured a barrage of harassment from anti-choice advocates for his role in prosecuting Randall Terry and other Operation Rescue protesters. After the 1988 protests and arrests, O’Brien’s office telephone was clogged for weeks with threatening phone calls from anti-choice demonstrators. They even picketed his home.

In addition, anti-choice groups have threatened to boycott any major pharmaceutical company that attempts to market RU486, the so-called “abortion pill.” According to The New York Times, drug company executives are so fearful of antiabortion groups, that they have hung back on efforts to get the drug approved for distribution in the United States.

Throughout its campaign of illegal intimidation, Operation Rescue has complained of unfair coverage in the media. On May 19, the group orchestrated a national protest of newspapers for their “distortion and censorship” of news on antichoice activities. During the protest, Operation Rescue ignored repeated requests for interviews from Southern Exposure. (See sidebar, next page.)

Randall and Petzelt say they tried to talk to protesters during the first few pickets at their clinics, but soon became frustrated with their inability to reason with the demonstrators. Now, they simply go about their business as best as they can and leave interaction to the police.

“One of the most disturbing things that happened to me during the protests in 1988, was just feeling very alienated from people,” Randall says. “I always thought there was something in common I could discuss with just about anybody — I could have a conversation at some level with just about any person I met. But I had absolutely nothing I could talk about with them. They would just stare at me and think I was going to hell and that was the end of the discussion. All they wanted to do was pray for me and condemn me to hell. I found that really disturbing.”

Petzelt agrees. “I don’t interact with them at all,” she says. “You don’t have a discussion with fanatics like that. The only way to survive is to pretend they don’t exist.”

Easier said than done. Clinic staff throughout the South manage to live with the death threats and daily harassment that make their jobs harder and their private lives less secure, but the broader effect of the protests is simply too large to ignore. Despite the recent Supreme Court ruling banning clinic protests, anti-abortion zealots remain determined to use whatever means they can find to limit reproductive options for women.

The number of protesters around the clinics has dwindled, but the terror continues. Kathy Collumb says she still needs new volunteer clinic escorts. And Lynne Randall still looks for her cats when she gets home from work.

Tags

Julie Hairston

Julie Hairston is a staff writer for Business Atlanta. (1990)

Julie Hairston is a reporter for Business Atlanta. (1989)