This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 2, "Birth Rights." Find more from that issue here.

Pensacola, Fla. —It was late 1983 when the anonymous letters about the city’s leading corporate citizen, Gulf Power Company, turned up in politicians’ offices, newsrooms, and board rooms.

The letters were crudely typed. Ungrammatical. The allegations were bizarre.

Northwest Florida’s electric company was a hotbed of corruption, the letters said, alleging everything from executives hiring prostitutes for a party to employees robbing the utility warehouse.

At first, the allegations seemed incredible, too ridiculous to believe. But Douglas McCrary, Gulf’s newly appointed president, ordered an inhouse investigation.

And, gradually, Gulf Power began to unravel.

Over the next six years, both the Internal Revenue Service and the FBI put Gulf under a microscope. Grand juries in two cities conducted probes. The utility’s sins spilled from its imposing $25 million building on Pensacola’s waterfront, creating a daily front-page soap opera. Eventually, nothing was too strange to believe.

The scandal ranged from burly Gulf warehouse supervisor Kyle Croft to the utility’s handsome, outgoing president Edward Addison, who was promoted to head Gulf’s huge Atlanta-based parent Southern Co. in 1983. It implicated scores of utility employees, top community and business leaders, and politicians, most notably state Senator W.D. Childers of Pensacola.

One bizarre event followed another:

▼A key grand jury witness, Ray Howell, vanished for a year after a desperate call threatening suicide.

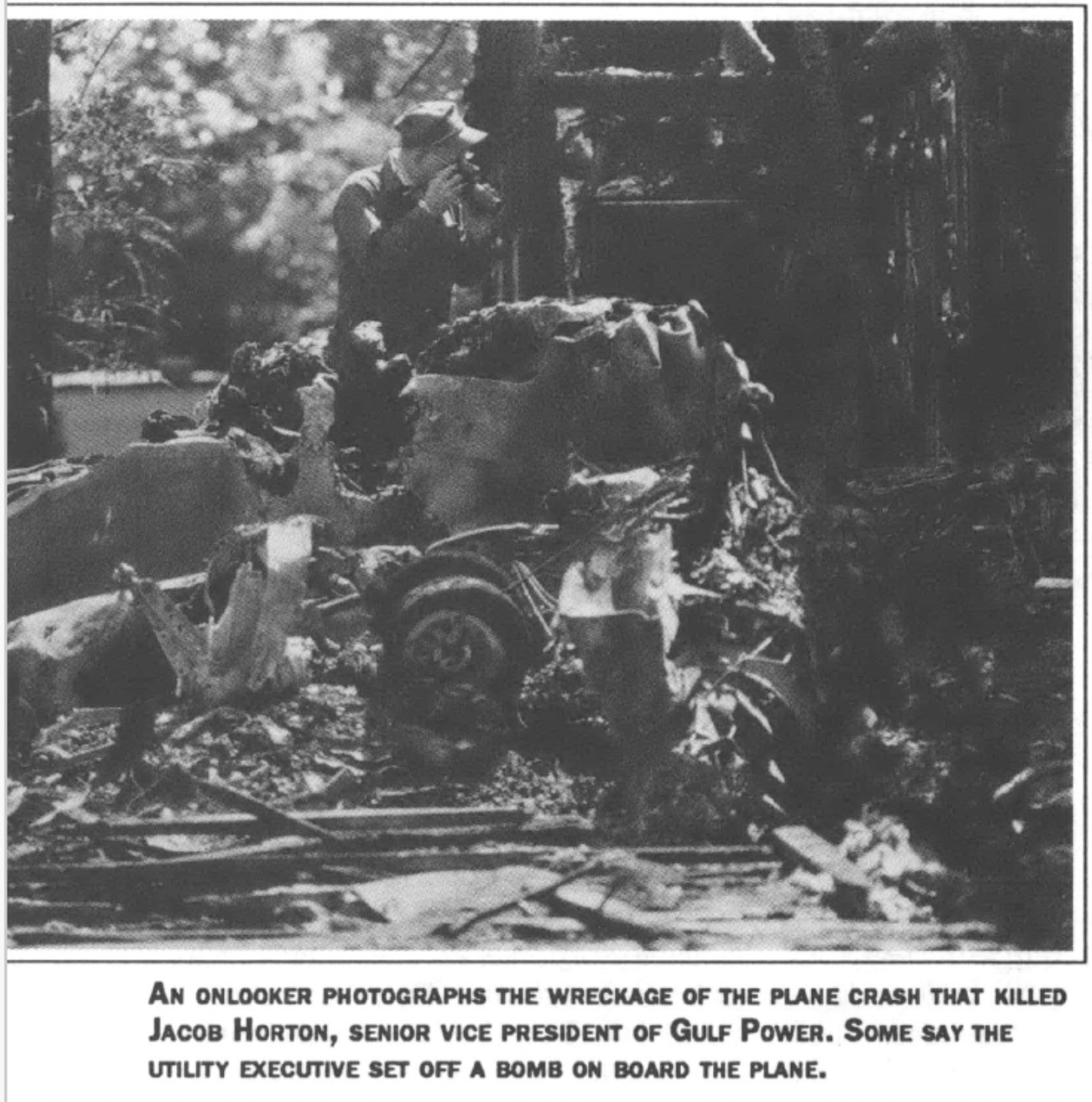

▼ Gulf’s senior vice president, Jacob Horton, a 33-year employee set for indictment, died in a fiery company plane crash an hour after he was told he would be ousted for his role in the scandal. Many believe he set the on-board fire that caused the plane to crash.

▼ A Gulf attorney and Horton pal, Fred Levin, found four canaries with broken backs on his doorstep—a sign he interpreted as a warning not to “sing” to investigators. The strange tale of Gulf Power provides a rare glimpse into the inner workings of a giant public utility. Gulf is one of five Southern Co. subsidiaries that supply electricity to over 3.2 million customers in Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. Granted a lucrative monopoly on a basic necessity and guaranteed a profit on its operations, the company used its power to steal from ratepayers, cheat on its taxes, and subvert the electoral process by creating a secret slush fund to conceal campaign contributions. So far, Gulf has pleaded guilty to two felonies, and two ex-employees and a company supplier have gone to prison. And by all indications, there is much more to come.

FROM WAREHOUSE TO BOARD ROOM

After the anonymous letters became public in January 1984, Gulf Power President Douglas McCrary hired two investigators from another Southern Co. subsidiary to conduct an internal probe. They interviewed numerous employees and decided that Kyle Croft, the warehouse and repair shop manager, was a major thief. Croft himself admitted that he ran the warehouse like his own fiefdom, helping himself to what he wanted. He stole transformers and other equipment for a company in which he held an interest. He sent his employees to help build his new home. He arranged for Gulf suppliers to provide wood for his kitchen cabinets and cement for his driveway, and then to send the utility a padded invoice. Croft’s total tab: more than $300,000. The investigators told McCrary what they had uncovered, and on January 29 he fired Croft. But Croft, a self-described redneck, decided he wasn’t going down alone. In a twist that has haunted the utility ever since, he revealed that company executives had ordered him to perform services and steal materials on thenbehalf. Sometimes he used utility employees to do the dirty work; sometimes he used company vendors. “I did so many favors for the executives that I felt it was only fair that I get something for myself, too,” he said. In his moment of need, Croft called on two buddies for whom he’d done a few favors: Senior Vice President Jacob Horton, a man who had his fingers in every civic pie in Pensacola, and state Senator W.D. Childers, a tough good ol’ boy with a reputation as one of the master political manipulators in the state. Horton and Childers, in turn, called on their buddy Fred Levin, an attorney and political pawnbroker who represented Gulf Power. The powerful trio, fast friends, met with McCrary and came up with an agreement: Croft was allowed to resign, keeping his pension and health insurance. In return, he signed a note to the company for $ 15,000; Horton gave him a note for the same amount. But Croft wasn’t satisfied with the deal. In June 1986, he filed a state civil suit charging Gulf executives with libel, slander, and extortion. He claimed they forced him to steal on their behalf, then made him resign as a scapegoat. Croft said he’d done numerous favors for top executives at company expense. He arranged for remodeling at the beach house of Edward Addison, then-president of Gulf. He arranged for painting and wallpapering at the home of Ben Kickliter, a company vice president. He had Horton’s house washed down and got him lawn sprinklers. Croft also said he had delivered briefcases of cash to various executives in parking lots. The list went on and on. Similar allegations had surfaced during the internal company investigation in 1984. “So many special jobs have been done for company executives... the nickname for the repair shop is ‘The Hobby Shop,”’ repairman Michael Box had said. “The men called the special jobs ‘007 work.’” EXECUTIVE THEFT Levin orchestrated the defense for the utility executives. They acknowledged that Croft provided them with “normal company perquisites,” but they denied he had been forced to conceal his activities. At the same time, the company revealed that Levin had set up an “amnesty program” after Croft’s thievery came to light. It was a chance for employees, their identities known only to Levin, to repay what they had stolen and clear their consciences. Levin said the amnesty program generated about $ 13,000, a fraction of what had been taken. What he didn’t say was that Edward Addison—by then the president of Southern Co.—had paid almost all of the amnesty. Addison, whose annual salary is almost $800,000, paid almost $ 10,000 in amnesty for what a Southern Co. spokesman called “everything that might possibly be viewed as being of more personal than corporate benefit.” Addison also paid Gulf another $7,907 for appliances he’d had for more than a year. He said he hadn ’ t noticed that he had never been billed. Despite the amnesty revelations, Croft lost his lawsuit. Thejudge who dismissed it in July 1988 said Gulf“had a right, even a duty... to fire a thief.” But he added that he was making no judgment about the allegations of executive theft. While his suit was pending, however, Croft went to the IRS and cut himself a deal. In February 1988, he pleaded guilty to a single count of impeding tax collection through a phony billing scheme. He was sentenced to a token four months and fined $ 10,000. In return, he gave the government information which led to the indictment of Lamar Brazwell, a former Gulf support services supervisor. In April 1988, Brazwell was charged with three counts of income tax evasion. According to the charges, he had received at least $ 131,319 in goods and services from Gulf Power vendors, many of whom had billed the utility for die expenses. He also owed $64,024 in taxes. Brazwell pleaded guilty to the three counts, which involved at least 13 different schemes with four vendors. He was sentenced to nine years and fined $30,000, and one of the vendors was convicted of peijury for lying about his role in the scam. And how did the company respond to revelations that vendors were billing the utility for kickbacks to employees? Instead of showing outrage, Gulf maintained contracts with most of the firms that took part in the schemes. Assistant U.S. Attorney Steve Preisser, who prosecuted the cases, said he’d never seen a victim less concerned about its losses. Finally, in mid-1988, the Pensacola grandjury probe came to a standstill. But for Gulf the greatest agony lay ahead. TESTIFY OR RUN In Atlanta, home of the Southern Co. parent operation, a federal grand jury investigation cranked up in August 1988. Initially the panel looked into allegations that Southern and its accounting firm hid $61 million in spare parts to avoid paying millions of dollars in taxes. Within a few months, however, the jury began reexamining the Gulf theft allegations and investigating charges that Gulf was making illegal political contributions. According to the allegations, Vice President Jacob Horton was secretly funneling campaign contributions through company vendors without the knowledge of president Douglas McCrary. Graphic artist Ray Howell, who had worked under contract for Gulf for 10 years, was subpoenaed to appear on December 8,1988—one of the first witnesses from Gulf. He never showed up. The night before, Howell had called Gulf public relations director Charles Lambert and said he had three options: Testify, run, or shoot himself. “He was extremely upset, frightened ... incoherent,” Lambert recalled. The next day, Howell simply disappeared. Howell’s one-man company, Design Associates, had only two significant clients: Gulf and state Senator Childers. He designed brochures and ads for both. Gulf employees said they couldn’t imagine what connection the genial “Gutf Power doesn’t have a speck of proof,” insists State Senator W.D. Childers, who has BEEN IMPLICATED IN THE SCANDAL. Howell could have with the investigation. Childers, who had paid Howell $ 133,000 during his fall campaign, said the same thing. But Gulf auditors subsequently reviewed Howell’s accounts and discovered astronomical, rising billings. In 1987, Gulf paid him $205,661; in 1988, $379,891. Other odd bits of information emerged. Howell had served a year in prison in 1977 for mail fraud. He also had a bank account in Austria. A magistrate issued a warrant for Howell’s arrest, charging unlawful flight. For the next year, IRS agents searched unsuccessfully for him, even staking out his mother’s funeral. THE SECRETPAC The Atlanta grand jury also heard a tale of two political action committees at Gulf Power. One—the Gulf Power Employees’ Committee for Responsible Legislation —was the utility’s legally registered PAC. The other—dubbed PAC II—was something else, and it raised eyebrows on the grandjury. The executive committee for the secret fund, which included Vice President Jacob Horton, decided which candidates were “good for GulfPower.” About 100 upper-management employees then contributed designated amounts, depending on their rank in the company. Some mailed checks directly to the candidates; others turned them over to their bosses. Every two years, the company used the unregistered fund to make political donations totaling about $ 11,000. Contributions were made in the names of individual employees, concealing the utility’s hand. Some employees complained of coercion. “You have to contribute to keep your job,” said one. Gulf officials, however, contended no one was forced to participate —even though 95 percent of eligible employees did. In fact, they added, PAC II wasn ’ t really a PAC. “It’s kind of anon-PAC,” said a company official. “It’s employee involvement.” Government attorneys said otherwise. According to a federal statement, Gulf Power used PAC II to coerce employees to make political contributions to candidates backed by the utility. “A PANDORA’S BOX” As the grandjury worked from the outside, one Gulf Power employee continued to probe company wrongdoings from the inside. Tom Baker had been promoted to corporate security manager after he uncovered the Croft warehouse scandal in 1984. He was a loyal company man who had worked for Southern Co. for 19 years. But his persistent inquiries into illegal activities higher up the corporate ladder were getting him in trouble with top management. Vice President Jacob Horton was particularly concerned about what Baker was learning. At one point, Horton admonished him, “I can’t operate in an atmosphere where security or anyone else is looking over my shoulder.” As Baker later recalled, “Horton told me that he was the most powerful man in Pensacola, the most powerful man in Florida, that he was Gulf Power and could run me out of town.” Finally, Baker was removed as security chiefand relegated to an outlying office as an investigator. He was told not to expect a raise for five or six years. Gulf insisted the transfer was part ofa company-wide move to “decentralize” security, but Baker was equally adamant that he was demoted for learning too much about wrongdoing. In October 1988, Baker presented Gulfs four-member audit committee, composed of the outside directors, with a 37-page report listing numerous allegations of illegal activities. “I love this company, and I have put it before everything in my life,” he told the directors, pleading for his oldjob. The audit committee decided Baker hadn’t been unfairly demoted—but it did investigate his allegations of wrongdoing, many involving Horton. What they found contradicted management reassurances that Gulf had been clean since the days of Croft. “Baker, as far as most of us are concerned, did us a favor,” said Dr. Reed Bell, a Pensacola pediatrician who chaired the audit committee. “He opened a Pandora’s box.” Bell and two other committee members became convinced that Horton had to go. The fourth member, Pensacola Mayor Vince Whibbs, defended Horton. On Friday, April 7,1989, with Whibbs out of town, the audit committee voted 3- 0 to recommend Horton’s ousting to the board of directors. The committee had the support of GulfPresident Douglas McCrary, ensuring a majority on the seven-member board. Horton would be allowed to retire, but would be fired if necessary. McCrary and Bell decided to tell Horton of the decision the following Monday. McCrary also asked Gulfattorney Fred Levin, a close friend of Horton, “to talk with Jake and get him to take a reasonable approach.” THE WEDDING RING Horton’s weekend was unremarkable. He got a haircut, visited his mother, did yardwork, tinkered with his antique cars, and made a routine visit to his office to pay bills. At about 9:25 a.m. Monday, Horton went to Levin’s office. Twenty minutes later, still in Levin’s office, he called the Southern Co. aircraft coordinator to say he wanted to go to Atlanta that afternoon for an hour-long meeting. The coordinator arranged a 1:00 p.m. take-off. Horton’s secretary called him at 10:20 and told him McCrary and Bell wanted to meet with him. Horton arrived at McCrary’s office at 11:30 and was told of the audit committee’s decision. McCrary said Horton took the news “very calmly” and said he’d get back with him that afternoon. It was obvious Levin had warned him. Horton went home around noon and told his wife, Frances, he was going to Atlanta to see Southern Co. President Edward Addison, his long-time friend and supporter. He didn’t say he was being ousted, and she didn’ t ask any questions. He washed up, removing his Auburn University ring, watch, and wedding band. He didn’t put them back on. Sometime that morning, he also wrote a $7,700 check paying offall but $74 of his home mortgage. He packed clothes for overnight but told Frances he’d try to get back so they could watch the country music awards on television that night. BOWLING BAG FIRE Horton drove up to the Southern Co. hangar at the Pensacola Regional Airport just as the Beech King Air 200 taxied in. Southern Co. pilots Mike Holmes and John Major, both 45, had made an uneventful flight from their home base in Gulfport, Mississippi, to pick up Horton. Holmes stayed on board; Major went into the hangar briefly. Horton handed luggage to an attendant, then went back to his car. He carried a bowling ball-like bag on board himself. The plane took off into drizzling, overcast skies at 12:57:52 p.m. At 12:59:17, Major asked, “What the hell was that?” At 12:59:19, Horton exclaimed, “Fire!” At 12:59:22, Major confirmed, “We gotta fire in back.” Two seconds later, he radioed, “Gotta emergency.” At 12:59:28, Holmes instructed Major to “dump the pressure.” There were no more transmissions. Witnesses watched the plane, trailing dark smoke, crash into a Pensacola apartment complex. Horton, 57, and the pilots died on impact. The seven people in the apartments escaped. Horton hadn ’ t told McCrary or Levin he had ordered the plane. Nor had he told anyone at Southern Co. he was on his way. Within hours, rumors swirled. Some people were convinced Horton had committed suicide. Others thought a Horton enemy had planted a fire bomb. Three hours after the crash, the sheriff’s department taped an anonymous telephone call. “Yeah, you can stop investigating GulfPower,” the male caller said. “We took care of that for them this afternoon.” An investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board concluded that there had been a fire in the passenger cabin. The agency said Horton’s “bowling bag” contained a Mason jar ring and cap and a t-shirt with traces of sulphuric and hydrochloric acids. Glass from thejar was scattered in the aisle. A book of matches was adhered to the outside of the bag. Eight hundred people packed the church for Jake Horton’s funeral. Pensacola Mayor Vince Whibbs delivered the eulogy. DEAD SONGBIRDS Fred Levin, a close friend of Horton, assumed center stage after the crash, seemingly relishing the role. He hinted he could shed light on the mystery, but insisted he couldn ’ t violate his confidential attorney-client relationship with Gulf and needed the utility’s permission to talk about his final conversation with Horton. By this time, however, Gulf and Levin were clearly on the outs. Levin’s loyalty was to Horton, and now, even with incriminating evidence, Levin was staunchly defending him. The company refused to release him from the attorney-client relationship, except to tell the grand jury and the FBI about his final conversation with Horton. Levin bellyached that Gulf was muzzling him. But he still managed to say plenty. He said he had found four dead canaries at his two homes and office. He assumed they were Mafia-type warnings not “to sing” about what he knew. He also announced that ex-heavyweight champion Tony Tubbs was moving into his home as a bodyguard. Finally, Levin announced his firm was quitting its $500,000-a-yearjob with Gulf because the utility had abandoned Horton. The grandjury subpoenaed Levin to its May session, and the FBI warned Levin that an informant had reported he would be “hit” before he testified. Levin made it to the grand jury, but a new death threat came in as he testified. A man with a raspy voice called an Atlanta attorney’s office to say Levin “would be blown away” as he left the courthouse. Five agents in bulletproof vests escorted Levin until he was delivered to the airport the next day. Levin said he told the grandjury Horton and Addison hadn’t done anything illegal. BUYING CLOUT As the grandjury probe dragged on, it took a heavy toll on GulfPower employees. Lineman Larry Woody said his barber told him, “You Gulf Power people, you got a mess. You’re right up there with the television evangelists.” Gulf executives and lawyers knew a trial would be lengthy, expensive, and demoralizing—and they didn’t believe they could win. So last October, the utility pleaded guilty to two felonies: conspiring to make illegal political contributions and to evade tax collectors through the creation of false invoices. The utility paid a $500,000 fine, taken from its stockholders. Without the plea, Gulfcould have faced more than 100 separate charges and a potential fine of more than $50 million. The plea agreement listed 123 illegal acts. It said Gulf illegally contributed about $43,000 to 20 politicians and about $23,000 to community events and groups, from a professional golf tournament to a junior college foundation. The plea said Horton masterminded a plan to force outside vendors, mainly four ad agencies, to make contributions to pet politicians and groups, and then to pad invoices to cover up the gifts. The plea agreement also revealed: T The Appleyard Agency, a Pensacola ad firm, used utility funds to pay a country singing group to perform at political and social events. Agency employees also cashed numerous checks and gave the money to a Gulf manager. T Gulfprovided a television studio and equipment for several candidates. T Gulf channeled money through the Design Associates ad firm to state Senator Childers’ 1988 re-election campaign. T Horton told a Pensacola billboard executive that Gulfneeded money for political campaigns, but that the IRS was watching too closely. The executive, who had a contract with Gulf, solicited $30,000 in cash after Horton told him he could submit inflated invoices. U.S. Attorney Robert Barr said Gulf had “subverted the electoral process” by concealing the true source ofcampaign financing. Restrictions on political contributions, he pointed out, are designed to prevent individuals or groups from obtaining undue influence with politicians. Southern Co. officials blamed the illegal deals on Horton. “For many years, Jake Horton was a trusted employee of Gulf and, as a result, was given a great deal of latitude,” a utility spokesman explained. “If someone who has earned trust fails that trust, then all the systems in the world won’t help.” If Horton did acton his own behalf, however, he was a highly unusual thief. After all, he never lined his own pockets —he simply used Gulf Power to do favors for friends and politicians and to buy clout for the company. “He was an angel, but a little bit ofa devil, too,” said a friend. “He was really a super-great person, but in order to be that way, he had to be a little bit corrupt.” Having confessed to a little corruption of its own, Gulf moved quickly to seek forgiveness. In November—a month after pleading guilty to two felonies— the utility filed for a $25.8 million rate increase with the Florida public service commission. RETURN OF THE FUGITIVE On December 27,1989, Ray Howell — the graphic artist who had vanished the day he was scheduled to appear before the grand jury—walked into the county jail in Pensacola. He didn’t say where he’d been for the last year. Federal marshals hustled him off to a series of undisclosed jails and finally to the maximum-security U.S. Penitentiary in Atlanta. In April, Howell pleaded guilty to contempt for fleeing and to a single taxfraud charge and promised to help the government. When he gets out ofprison, prosecutors have promised to submit his application to the witness relocation and protection program. But the reappearance of Howell has sparked another probe into the trail of illegal political contributions at Gulf Power. After talking to Howell for two days, IRS agents are reportedly involved in a full-scale investigation of state Senator Childers, a prominent powerbroker in the Florida legislature for 20 years. If the new investigation is any indication, the story of GulfPower and its political machinations may be far from over. Childers says he has done nothing wrong and has vowed to fight any allegations. In fact, he still insists that Gulfnever funneled money to him through Howell’s company—even though the utility has pleaded guilty to the charge. “Gulf Power doesn’t have a speck of proof,” Childers said. “They better put up or shut up.”

Tags

Ginny Graybiel

Ginny Graybiel has investigated the Gulf Power scandal for five years as a reporter for the Pensacola News Journal. Her stories won a 1989 Southern Journalism Award for investigative reporting from the Institute for Southern Studies. (1990)