This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 2, "Birth Rights." Find more from that issue here.

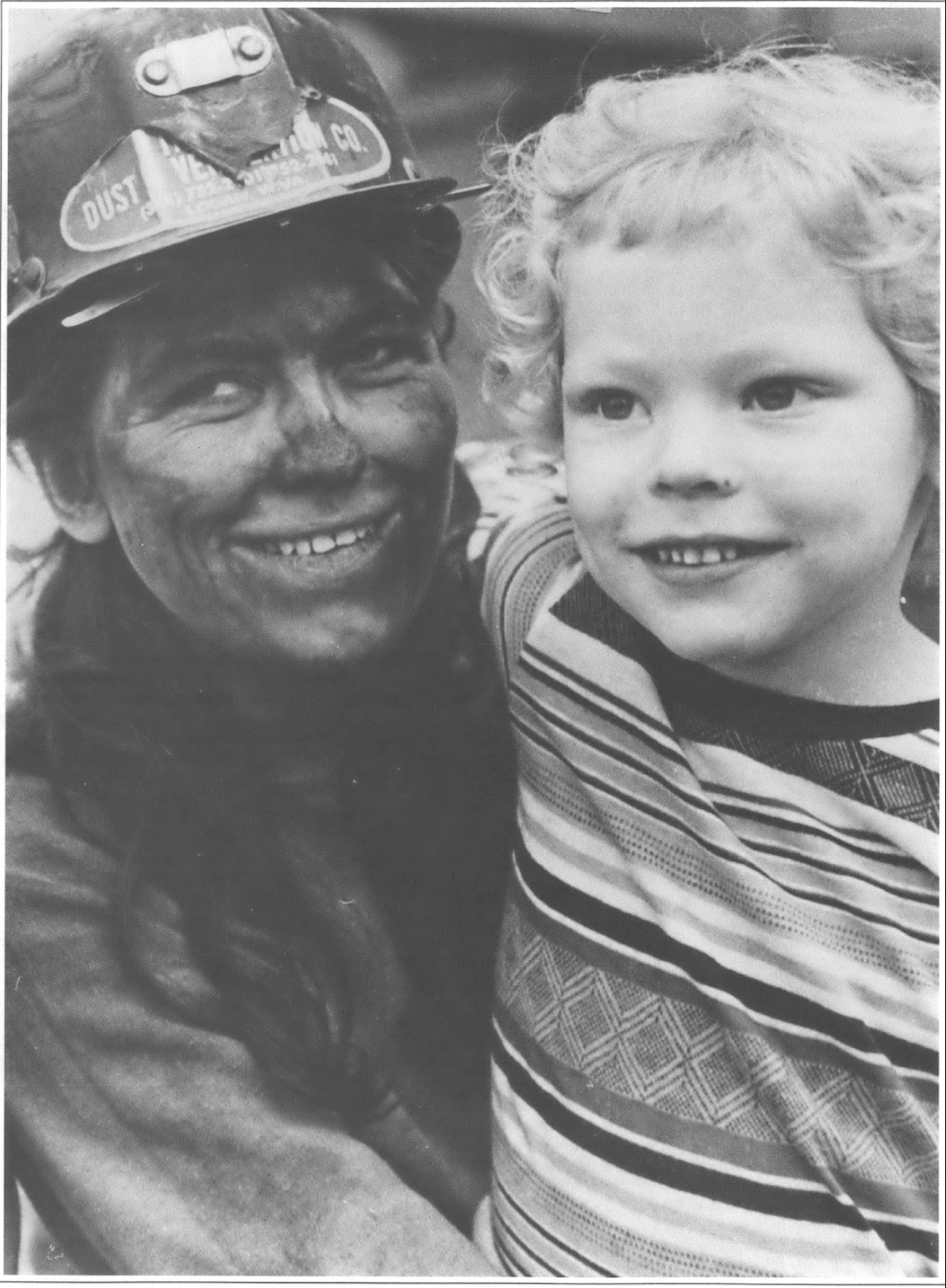

Tazewell, Va. — The year her daughter got sick, Cosby Totten’s Thursdays became a grueling seven-hour marathon from her home in Virginia to her coal mining job in West Virginia and the doctors at Duke University in North Carolina.

“I’d go to work at four o’clock of an evening, get off at midnight and go get Goldie Carol,” recalled Totten, a divorced mother of six. “We’d drive to my sister’s house in North Carolina, and she’d take her on to the hospital while I rested up for the drive back.”

Like many single parents, Totten found herself caught between the demands of her job and the needs of her children. “People shouldn’t have to make that choice,” she says.

Totten was among the first women to go to work underground, but her reasons had more to do with the paycheck than a feminist assault on male tradition. “I really wanted to stay at home with my six,” she said. “But a woman can’t stay at home and take abuse from a man just to raise your kids.

“I had six good reasons to go to work in the mines.”

In 1982, when her daughter Goldie began experiencing mysterious seizures at school, Totten worked at the Consolidation Coal Co. Bishop Complex in McDowell County, West Virginia. It was one of the best jobs available in rural Appalachia, bringing her wages of up to $12 an hour and good health insurance under the national coal contract negotiated by the United Mine Workers.

The contract also gave Totten five “personal leave days” that she could use any way she chose. But once the leave was exhausted, a punitive absenteeism policy allowed the company to fire her if she missed two “unexcused absences” in a row for any reason other than her own “proven” sickness. When Goldie got sick, Totten was forced to juggle doctor appointments around her work schedule, and thus began the marathon Thursdays that blurred into Fridays.

“God forbid, you take two days and get fired,” Totten said. “Then where are you? A sick kid, no job and no insurance.”

Unlike some, this story had a happy ending: Goldie Carol, whose mysterious illness proved relatively easy to cure once a correct diagnosis was made, is now a robust 22-year-old, Totten’s “fourth one down.” And Totten turned her experience into a successful campaign to get one of the nation’s bastions of blue-collar masculinity — the United Mine Workers of America — (UMWA) actively involved in the national fight for family leave.

Those who lobbied for the family leave bill that recently passed the House of Representatives say the support of the Mine Workers was one of the keys to their first real congressional victory. On May 10 — five years after the measure was first introduced — the House voted 237 to 187 to require companies with 50 or more employees to provide up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave a year to care for newborn or newly adopted children or seriously ill family members. The measure was sent to the Senate.

“The Mine Workers were instrumental in getting it to this point,” said Donna Lenhoff of the Women’s Legal Defense Fund in Washington, D.C. “We could not have gotten it to this stage without the serious support of the AFL-CIO and the entire labor movement, and we wouldn’t have gotten that without the Mine Workers.

“They educated the rest of the labor movement — and not just those unions with predominantly female memberships, but also all those macho, male unions.”

Fathers and Hearts

If any union qualifies as male-oriented and “macho,” it’s the Mine Workers, which remained unassailably male until the mid-1970s. By the early 1980s, the union had about 3,000 women members; today, after the most recent coalfield recession, there are fewer than 1,500 active women members. They amount to about one percent of the union’s membership.

Despite those daunting numbers, Totten and other miners — male and female — who became involved in the family leave campaign say they found an extremely receptive audience among international officers and rank-and-file members alike.

“It was easy to convince them, because they’re all fathers,” said Totten. “They’ve got hearts, too; the Mine Workers have got the best hearts in the world. If they didn’t care about their wives and children, they wouldn’t work in the coal mines.”

The initial goal of Totten and her coworkers was to have the UMWA make parental leave a collective bargaining issue. One of their first stops in 1983 was the union’s international offices in Washington, D.C., where they talked with UMWA Vice President Cecil Roberts and, later, with President Richard Trumka. Trumka said the issue was a natural one for the UMWA.

“Unlike a lot of unions, the whole concept of the Mine Workers is built around the family — not the shop floor,” said Trumka. He points to a variety of national contract provisions aimed at miners’ families, like a training and education fund that provides benefits not only to unemployed miners but also to their spouses and dependents. “We’ve always looked on our jobs as a way to provide for our families,’’ Trumka said.

Those attitudes are the result of a combination of cultural attributes that may be unique to the Mine Workers. The members, many of them second- and third-generation miners, live almost exclusively in rural areas, often alongside their parents and grandparents. It’s a situation where family is bound to play an important role.

“Once they choose somewhere to set down roots, they stay in that area,” Trumka said of his members. “They go into the mines the way my dad took me into the mines, the way he was taken into the mines by both my grandfathers.

“They identify their support system as their family first, their extended family and then their union,” he said.

It was concern for their families, for example, that finally forced miners to end their bitter contract strike of 1977, which focused in part on health care issues. Without a dollar in strike benefits, the miners stayed out for a record 111 days, ultimately stifling coal production enough to dry up pension funds that ran on production royalties. When the pension checks stopped coming, the reaction was swift: miners willing to do without for themselves returned to work for their parents and grandparents.

Men at the Top

Despite this emphasis on family, female members of the union were rare until the mid-1970s, when women began to insist on their right to work underground alongside men. By 1979, when 1,500 UMWA members met in a constitutional convention in Denver, they were joined by the first 10 women delegates ever elected to represent their local unions.

“That first time in Denver, most of the women really didn’t want to draw too much attention to themselves,” recalled Betty Jean Hall of the Occupational Safety and Health Law Center in Washington, D.C. “But there were some who felt they were making history whether they wanted to or not, and that they had some obligation to make a statement as women, as a group.

“The one thing they could agree on was that they didn’t want anything for themselves that they couldn’t get for their union brothers,” said Hall, who at the time was director of the Coal Employment Project, a group she founded in 1977 to help women gain jobs in coal mining and other non-traditional industries.

According to Hall, nothing much came out of the women’s Denver discussions — “except for the idea of maternity-paternity leave, that this would be the obvious issue for us, something that was of importance to the men as well as the women, something that we could work together on.”

June Rostan, a former Coal Employment Project staffer who now directs the Southern Empowerment Project in Knoxville, Tennessee, recalls that the discussion at first focused on how hard it was for female miners to get maternity leave. “But they realized that you couldn’t win it on that basis, and that times were right to think of it as maternity-paternity leave,” Rostan said.

“As they talked to the men, the women found that the receptiveness by their male co-workers was much more positive than they expected. I think it was because it came at a time when the role of the father was beginning to change, even in working-class families.

“A lot of the men had experienced trouble in caring for a sick child,” Rostan added. “Miners live in rural areas, and regional medical centers tend to be out of the coalfields, involving long travel.

“The proposal just never met the opposition that I expected it would get — I think because the campaign was pitched to men,” she said. “It addressed their self-interest, too.”

Interest was also evident on the part of the international union and its top officers. Several international staff members had been granted leaves to take care of family matters, including the birth of children.

“Part of the reason was that the union’s top officers are younger men, and Trumka put a real priority on hiring miners for the staff,” said Rostan. “They had a different idea of family roles. They were part of that generation that had begun to re-examine the roles we grew up with.”

Planning a Picnic

With the support of the Coal Employment Project, women miners held several conferences to devise a strategy for bringing the issue to the attention of the UMWA rank and file. They studied the union’s constitution to leam how collective bargaining issues are determined; Rostan said the UMWA is unusual in having a constitution that clearly spells out the rules for rank-and-file miners to bring issues to the attention of their leaders.

“They learned the rules of the game and they followed the rules,” Rostan said of the women.

That was the start of a carefully organized and detailed grassroots campaign. In each of the union’s 21 districts, women went to work, approaching their male coworkers in creative ways. One woman volunteered to coordinate a company picnic just so she could talk about parental leave with her male co-workers as she planned the picnic.

“In the beginning, we just generated discussions among the members,” said Steve Webber, a West Virginia representative on the UWMA governing board who was among the first union officials approached by the women. “But those discussions quickly brought out a number of male miners who had had problems with family and couldn’t get time off when they needed it. After the discussion got started, it was easily recognized as a problem that everyone had — not just women.”

In every district, the women found male and female miners who had been unable to get family leave when they needed it:

· To keep from losing his job, Fred Decker of rural Wyoming County in West Virginia regularly drove 400 miles round-trip to take his son for leukemia treatments.

· Nancy Bowen of Williamson, West Virginia was forced to quit her job to take care of a comatose son, only to be denied unemployment benefits because she missed work while her son was ill.

· James Callor of Helper, Utah was denied permission to take a week off from work to spend with his six-year-old daughter just before her death from cancer of the nervous system.

Nationwide, the parental leave campaign gathered momentum as a collective bargaining issue for the UMWA. Success became apparent at the union’s next constitutional convention, which convened in Pittsburgh in 1983. When the collective bargaining resolutions proposed by local unions were tallied, parental leave was third on the list behind pensions and health insurance.

“Not only was it number three in the number of resolutions, but the resolutions were evenly distributed geographically — so there really was a groundswell,” said Rostan.

As a result, parental leave had a prominent place at the bargaining table when the union sat down with the nation’s coal operators in 1984. At a time when other unions were being forced to accept concessions, the UMWA adopted a bargaining stance of “no backward steps” — and added a contract demand for parental leave.

According to Webber, the parental leave demand was the last issue to come off the table before the union settled its 1984 contract with the Bituminous Coal Operators Association. After difficult negotiations, the two sides agreed to establish a special Parental Leave Study Committee. An even tougher round of negotiations in 1988 allowed for no further progress on the issue, Webber said.

Despite the lack of progress at the bargaining table, the UMWA has continued its emphasis on family leave, playing a major role in the congressional fight. Although her children are grown now, Totten still fights for parental leave and thinks the time will come when government or industry will have to recognize the importance of family health.

Most other industrial nations already accept the need for family leave. Italy, Germany, and Sweden all provide at least 14 weeks of paid leave for new mothers. In Canada, mothers can get up to 41 weeks of parental leave at 60 percent of pay, while in Chile either parent is eligible for 18 weeks of parental leave at full pay.

“These U.S. companies who are fighting this thing — where in the hell do they think the future workers come from?” demanded Totten. “I think people ought to say ‘no more children’ until we get some of these things worked out. That ought to be one of our strategies.”

Tags

Martha Hodel

Martha Hodel is on sabbatical from the Associated Press in Charleston, West Virginia, where she has worked since 1976. (1990)