This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 2, "Birth Rights." Find more from that issue here.

Athens, Ala. — It was a new job as assistant manager at the Huntsville Home Depot that lured Kenneth Issacs and his wife Kandy here from their native Kentucky last year. They were barely settled in their new home when Kandy found out she was pregnant with twins.

“We were really excited . . . and a little scared,” recalled Kandy, a lanky 26- year-old. Kenneth had a steady income — but that, the couple discovered, was a problem. They were making too much money to qualify for Medicaid, but nowhere near enough to afford private health insurance.

When the Issacs set out to find a local doctor to provide maternity care, they were in for another shock — there were none. The last two physicians who delivered babies in Athens had dropped obstetrics from their practices, citing high malpractice insurance premiums.

Huntsville, the closest city, was little better. The only clinic for uninsured pregnant women had a six-month waiting list just to get an appointment, and the public hospital required a $1,200 down payment for out-of-county patients like Kandy Isaacs.

Finally, the couple found the Athens Maternity Center, a new clinic set up by the local hospital to avoid losing revenues from pregnant patients abandoned by local doctors. The Issacs managed to come up with the $665 down payment, and their twins — Aaron and Elizabeth — arrived by Cesarian section on January 17.

The $6,000 bill arrived later. “We’re in debt up to our necks now,” Kandy said with a wry grin as she changed Aaron’s diaper. “It’ll take us 20 years to pay it off.”

The obstacle course the Issacs faced in their search for maternity care has become all-too-common for pregnant women in the South. In fact, things in Alabama are so bad that the U.S. Government Accounting Office branded the state “the worst place in the country to have a baby.”

Alabama has the highest rate of hospital closures in the nation, and doctors are quitting obstetrics and turning away from poor women in droves. Twenty-nine counties currently have no doctors who deliver babies, and pregnant women in rural areas who go into labor often have to race 50 miles to a hospital emergency room to find a physician willing to attend their births.

The epidemic of doctors refusing to deliver babies has left uninsured women and their children at risk. Deprived of adequate prenatal care, hundreds of Alabama infants die each year. A baby born in Singapore or Bulgaria today has a better chance of living to see its first birthday than a black child in rural Alabama.

Closing the Doors

Access to maternity care in Alabama has not always been so bad. During the 1970s, the number of doctors in rural areas actually increased, thanks to federal programs that subsidized rural hospitals and provided low-interest educational loans to medical students planning to work in underserved areas.

But all that changed when Ronald Reagan became president. Instead of backing national health insurance — a system enjoyed by every other industrial nation in the world except South Africa — Reagan pushed doctors and hospitals to compete even harder for privately insured patients. He gutted rural health-care programs and cut hospital reimbursements for elderly Medicare patients.

Rural hospitals, long reimbursed at lower rates than their urban counterparts, suffered the most. Some sold out to private hospital chains, which promptly began turning away poor patients and closing rural facilities that failed to turn a profit. In Alabama, 10 hospitals closed their doors in 1987 and 1988 alone; eight of them were rural.

At the same time, doctors began complaining about the rising cost of malpractice insurance. Obstetricians get sued more than any other medical specialists, and insurance companies began to jack up their premiums.

Before long, the number of rural doctors delivering babies also began to plummet. According to a report by the Institute of Medicine, the states hardest hit by the loss of obstetric services were Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, and West Virginia.

In Alabama, state medical surveys show that a third of all doctors who delivered babies quit obstetrics between 1980 and 1986. Since then, health researchers estimate that more than half of the remaining rural practitioners have dropped out, leaving pregnant mothers in the northeastern Appalachians and the central “black-belt” farm counties without any maternity care.

Dr. Bryan Perry held out longer than most of his colleagues. By 1986 he was the only doctor still delivering babies in the impoverished mountain region of Cherokee County. His caseload soared to 68 births a month — more than two deliveries a day.

“It pins me down. I’m working myself to death. But I don’t want to give it up,” he said at the time.

But the pressure was too much. A year later Perry quit obstetrics, leaving pregnant women in Cherokee County without a single doctor willing to deliver their babies.

Emergency-Room Shuffle

The drought of rural doctors and hospitals had an immediate effect on expectant mothers and their babies. Between 1980 and 1987, studies show, the number of pregnant women receiving no prenatal care increased by 50 percent. Without insurance or a family doctor, many working-class women were forced to rush to hospital emergency rooms after they went into labor.

Emergency-room doctors in Montgomery soon noted a three-fold increase in the number of high-risk “walk-in deliveries” they were handling for poor women with inadequate prenatal care. Fearing lawsuits and further hikes in their malpractice rates, local obstetricians threatened to boycott deliveries of indigent babies until public officials addressed the problem.

The health department responded by setting up a program to rotate “ER” service among the three hospitals in the city. The plan spread the malpractice risk around — but it did nothing to provide better maternity care.

“Pregnant women were basically being shoved in and out of the health department,” said Doris Barnette, acting director of the state Bureau of Family Health Services. “They listened to the radio to see what was the ‘ER-of-the-day.’ The only thing they could be sure of was that they would be delivered by a physician they’d never seen before.”

Sherry Thomas, a 23-year-old Montgomery resident, was pregnant with her second child when the emergency-room shuffle was established. She saw a private doctor for a while, but then she changed jobs and lost her insurance. After that, she went to a public clinic for prenatal care.

When Thomas went into labor the morning of January 18, 1986, she waited until the contractions were two minutes apart before rushing to nearby Baptist Medical Center, the “ER-of-the-day.” The doctor on duty was attentive — until he discovered that she was not a private patient.

“I told him I was in labor because I was hurting so bad,” Thomas recalled. “But he told me there was nothing he could do; to go home.”

She pleaded with the nurses as they took her to her car, but to no avail. After she got home Thomas called the assistant to the private doctor she’d seen earlier in her pregnancy. He first told her to return to Baptist, but then called back to say the “ER-of-the-day” had been switched at 7 a.m. She would have to go to Jackson Hospital — 11 miles away.

She didn’t make it. Her son was born in the car on the way to Jackson.

Bad Medicine

Dr. Joseph Ferlisi, who treated Thomas after she arrived at Jackson Hospital, is also the spokesman for the Montgomery County Obstetrical Society. He defended the physician threat to strike and expressed frustration over the lack of official concern over the state’s incomplete system of health care.

“At no time have we asked for more pay,” Ferlisi said. “What we’re asking for is a change in the system.”

The “change” Ferlisi and other physicians wanted, however, had nothing to do with better access to health care. Instead, doctors lobbied for a state-imposed limit on the amount of damages awarded to patients harmed by doctor malpractice. If malpractice awards were smaller, the doctors said, insurance rates would go down — and physicians would start delivering babies again.

In 1988 doctors got what they wanted. The state legislature passed a ceiling on malpractice damages — but the problem didn’t go away.

“Two years later have their premiums gone down? No way,” said Jane Patton, a Montgomery attorney and a consumer advocate on the state Task Force on Infant Mortality. Insurance companies, she explained, won’t lower their rates until the malpractice limits have been tested in court.

The real problem, many health-care professionals say, lies with the control doctors exercise over who receives care. “This is a conflict between private medicine and public health,” said Dr. Robert Goldenberg, an obstetrician with the University of Alabama School of Medicine.

“Unlike most state health departments, which are controlled by public health professionals, our board of health is controlled by the Alabama Medical Association,” Dr. Goldenberg added. “Since doctors make up the board, it has been less aggressive than it should have been in making public health policies.”

Twin Casualties

As Alabama doctors lobbied for lower penalties for their own malpractice, health-care options for poor women continued to dwindle — and statistics on infant deaths continued to rise.

Josephine Lewis watched her twin daughters become two of those statistics. A 22-year-old native of Greene County, Lewis had dropped out of school and was already a mother of five when she became pregnant again in 1985.

Although problems with previous pregnancies made Lewis a high-risk patient, she did not seek medical care until her sixth month. One reason was lack of transportation — she had no car and depended on friends to drive her to the clinic in nearby Eutaw.

Then, in her 24th week, she delivered prematurely. She was so far along in labor when she arrived at the hospital that she gave birth in a hallway.

One twin, Tarneisha, died shortly after the birth. The other, Starneisha, spent two months in a newborn nursery gaining weight. She was up to five pounds when she was released from the hospital.

Two weeks later, Lewis was unable to wake the infant at feeding time.

“I thought she was just sleeping,” Lewis later told the Alabama Journal. “I couldn’t believe this could happen to me.” The cause of death was unknown.

When infant mortality statistics were released the following year, Alabama ranked last in the nation with 13 deaths for every 1,000 births. Each year, at least 10 Southem states consistently report higher infant death rates than the rest of the country.

The U.S. currently ranks 18th among developed nations for its infant death rate, and babies in many rural counties of the Deep South are more likely to die than newborns in many Third World nations.

The reason: Southern women are more likely to receive inadequate prenatal care and to give birth to underweight babies. What’s more, the gap between black women and white women has widened. According to a 1989 study by the Children’s Defense Fund, the birth risks for Southern black women are roughly twice as high as for whites.

Southern politicians continue to plead poverty, saying they cannot afford public programs to protect mothers and infants. Ironically, though, studies show that every $1 invested in better care for pregnant women saves $3 in long-term costs for newborn intensive care and rehabilitation of handicapped children.

Stingy Policy

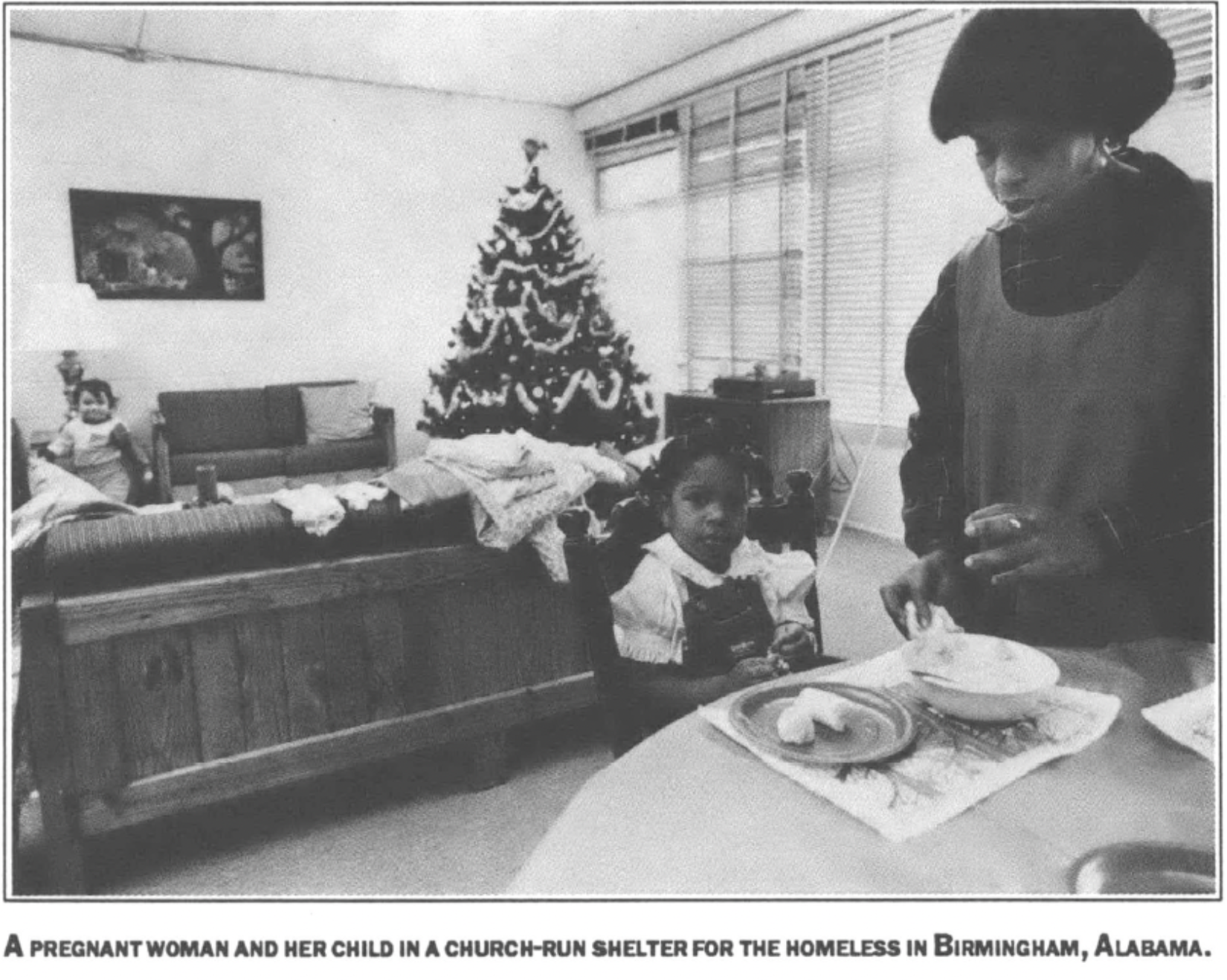

As publicity over high infant death rates spread, public health advocates began to push for expanding insurance to cover more poor mothers and their infants. Alabama had the stingiest public insurance program in the country, with only 15 percent of all patients in county health clinics covered by Medicaid.

Doctors in the Alabama Perinatal Association joined forces with the Foundation for Women’s Health to form a new lobbying group known as Partners, which won the support of State Health Officer Earl Fox.

The group also found an unexpected ally in the federal government, which in 1988 required states to extend Medicaid coverage to all pregnant women living below the federal poverty level. In April 1990, another federal mandate expanded coverage to women with incomes up to 33 percent above the poverty line.

In addition, Partners succeeded in pushing the state to increase Medicaid payments for deliveries from $450 to $718.

Dr. Fox and the new group also tackled the doctor shortage in Montgomery by establishing a “Gift of Life” program to handle prenatal care and deliveries for poor women in the city. The program recruited three out-of-state obstetricians to share the caseload with seven nurse-midwives.

A friend told Annette Posey about the program last fall when she began to bleed during her third month of pregnancy. The 23-year-old Montgomery resident lost her first baby four years ago, and she feared another miscarriage. Posey visited nurse-midwives at the clinic 18 times before giving birth to Stephen, a healthy 6-pound, 14-ounce boy, on March 8.

“I was so glad. I felt like the nurse-midwives did more than my other doctor did,” said Posey, who depended on Medicaid for care in both pregnancies. “Everybody at the Gift of Life was friendly and they knew me by name when I came in. I felt like they understood me better.”

Doris Barnette, an assistant to Dr. Fox, said the success of the program has created a rising demand. “I’d like to have 100 nurse-midwives,” she said. “I could place them all in jobs in one afternoon.”

But the city clinic and the expanded Medicaid coverage were of little help to Kandy Issacs and other rural women. Many in the ranks of the working poor still do not qualify for Medicaid — and still cannot find a doctor even if they do qualify. According to the Southern Growth Policies Board, more than a fifth of all Southerners under the age of 65 are without health insurance.

Look Homeward

Along the backroads of Alabama, health advocates are taking a hard look at the refusal of doctors to deliver babies, and they are asking a deceptively simple question: Do we really need a doctor for every birth?

The question strikes at the most basic assumptions of the medical establishment, and opens up a range of alternatives that go beyond expanding health insurance and lowering malpractice rates. If birth is seen as a natural family process rather than an illness that must be treated in a high-tech hospital, then perhaps babies can be delivered by someone other than a doctor.

In Greene County, where Josephine Lewis lost her newborn twins because of inadequate care, Dr. Sandral Hullett is trying an alternative. Hullett, one of the few black woman doctors in the region, delivered Josephine’s twins in a hospital hallway. She knows first-hand how desperate women are for prenatal care.

To fill the void left by malpractice-minded doctors, Hullett has turned to lay “home visitors” to promote prenatal care for pregnant women. For the past five years, she has recruited and trained dozens of elderly black women to serve as role models for pregnant teenagers.

“Lay women were delivering health care in homes hundreds of years before professionals got into the act,” Hullett observed.

There are plenty of signs that the plan is working. Angela Young, unmarried and still in school at age 17, never told a soul that she was pregnant — that is, not until a lay home visitor named Margaret Means heard a rumor and came to visit her.

“I didn’t even tell Mrs. Means at first,” Angela recalled with a grin. “We were sitting on the sofa talking and then she asked me, ‘How many months along are you?’ She encouraged me to go to a doctor.”

Angela smiled and showed off her seven-month-old daughter Lucretia. “I needed someone to talk to,” she added. “I don’ t know what I’d have done without her.”

Means, a soft-spoken 67-year-old whose living room overflows with photos of her grandchildren, says home visitors are gaining the trust of local women. She likes to tell the story of a young woman who called her to report that she was in labor before she told her own mother in the next room. “That’s when I knew I’d made it,” said Means.

Such personal stories are backed up by a recent study which indicates that women in the program who received home visits gave birth to babies that needed significantly less intensive care than women who were left to find their own way through the health system. None of the 105 babies tracked by the study has died.

The grassroots success in Greene County has won supporters in state government. State Health Officer Earl Fox called it “an excellent example of programs that should exist all over the state.”

People-oriented efforts like the home-visitor program prove that poor women can be given greater access to reproductive health care — and that reducing the need for expensive neonatal intensive care will actually reduce state health costs.

Alabama public health advocates agree, however, that such programs will only be implemented on a large scale when health-care workers and consumers challenge the control over health priorities so long enjoyed by physicians.

“There is an unwillingness to admit that we have a two-or three-tiered medical system,” said Suzanne Ticheli, a researcher at the University of Alabama School of Public Health. “Until we look at these realities we’re not going to come up with integrated solutions.”

Tags

Sandy Smith-Nonini

Sandy Smith-Nonini is an adjunct assistant professor of medical anthropology at the University of North Carolina Chapel-Hill and a former investigative reporter for Southern Exposure, the print forerunner to Facing South.