This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

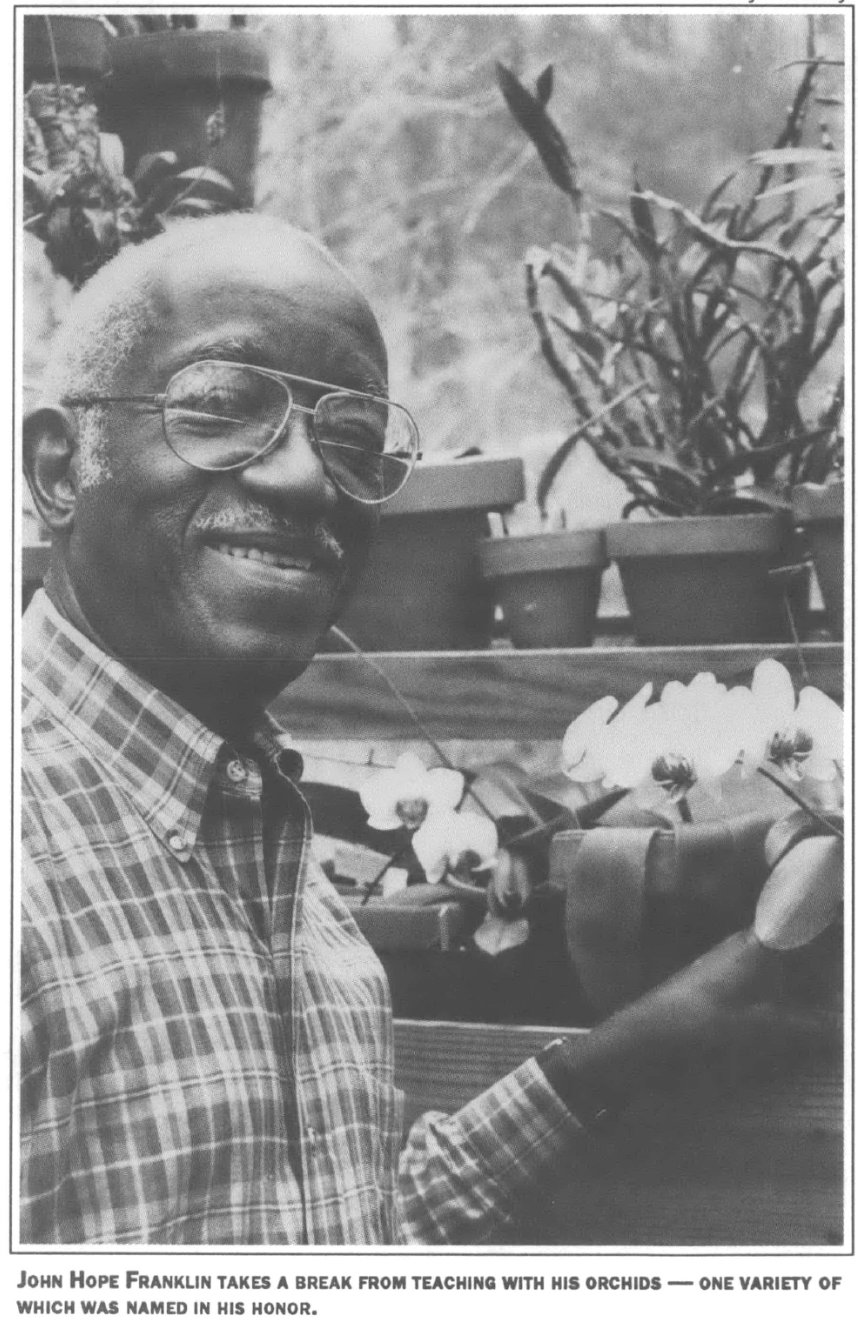

John Hope Franklin is a neighbor of Southern Exposure. He works just down the road at Duke University, where he is James B. Duke Professor Emeritus and Professor of Legal History at the law school.

Franklin came to Duke to culminate a long and illustrious career. At age 75, he has chaired the history department at the University of Chicago, received more than 75 honorary degrees, and authored numerous books, including The Emancipation Proclamation and From Slavery to Freedom.

But Franklin has not limited his activities to the classroom. He participated in the historic civil rights march at Selma, Alabama in 1965, and has devoted much of his creativity to his impressive collection of orchids.

Perhaps most important, Franklin has served as father to an entire generation of African-American historians. Through his scholarly work and his enormous generosity as a colleague, he has helped bring a diversity of voices to the profession of history.

On a recent afternoon we met Franklin on campus and talked about his study of the Civil War.

SE: Tell us about your own experiences growing up. How did you first learn about the Civil War?

JHF: I grew up in Oklahoma in a village near Honey Springs. There was a battle during the Civil War called the Battle of Honey Springs, and we used to walk down to the battlefield and pick up Indian arrowheads. I knew there had been a battle there but knew very little about it.

I suppose my first memory of the war is my father telling me, as a small boy, about how his father ran away and enlisted in the Civil War. That memory was later confirmed by documents regarding his efforts to get a pension.

My first real confrontation with the war was in college, when I decided to major in history. I began to look at the Civil War and the whole 19th century rather seriously, and I’ve been writing about that period ever since.

SE: It’s easy to forget, now that archives are integrated, the kind of obstacles that black scholars ran into. What kind of barriers did you confront in trying to research the war?

JHF: In North Carolina I ran into the first big obstacle. I was informed by the then-director of the state department of archives and history that I was not allowed to do research there. But he conceded that perhaps I did have a right to do it, so he said, “If you’ll give me a few days, I’ll make some arrangements.”

This was a Monday, and he wanted a week. I just looked at him, because I was paying rent, and eating. He said, “Well, how about Thursday?”

I went back Thursday and they had stripped a room in the museum part of the archives. They had pulled out all the display cases and put in a bare desk and a wastebasket, and that was my study room. It remained my study room for some four years.

When I went to Alabama, I was even afraid to go to the state archives. I thought it would be much worse than North Carolina. When I finally worked up enough courage to go in the summer of ’45, I was working on a book on Southern militancy, which always appealed to people in archives because they thought I was singing the praises of the South’s martial tradition — the Citadel and VMI.

I went in and told the woman in charge of the research room what I wanted. She brought me all the material and handed it to me. I just stood there, looking at her and looking around. By then, I was like Pavlov’s dog — I was waiting for the signal.

Some white people were doing research in one section of the room, so I started to go to another part, just so I’d have a quiet place to do my work. But when I started toward that corner, the woman said, “You can’t sit over there.”

My reaction was, “Well why didn’t you tell me I had to go to the basement in the first place!” But she said, “That’s the hottest part of the room. The only cool place is over here with these other people, where the fan is. They need to meet you anyway.” And she stopped everybody and introduced me. So I sat there at the same table with these white scholars, with the Confederate flag waving over the archives building.

I left there and went to Louisiana. I arrived in Baton Rouge the week World War II ended. There was a great celebration, and everything was closed. The archivist said I would not be allowed to do research there because they didn’t allow blacks into the building to do anything except clean it.

Then he said, “I’ll be up here this week catching up on some paperwork. If you want to do research, you can come then. I don’t care.” So the only reason I was able to do research there was the fact that the archives were closed to celebrate the great victory of democracy over totalitarianism.

SE: What are some of the connections between what’s happening today in places like Selma and South Africa and what happened during the Civil War?

JHF: The general American public needs to know so much more about the history of their country and the place of blacks in that history. There hasn’t been a moment since 1619 that blacks have had an insignificant part. But people don’t make that connection. People still say, “Well, if you don’t like it here, go back where you came from,” as though we weren’t here when they got here! We’ve been here. And white people need to know that. They need to know that this state, this region, this nation was cleared, tilled, and developed by black hands as much as white hands, if not more so.

When blacks talk about the need to know our history, I say, “Listen: You don’t have enough power to be the only one who needs to know your history. What you need is to put information in the hands of people who do have some power, so that the sharing of power can make more sense.”

For example, they need to know that in the generation before the Civil War, enormous numbers of whites from Europe came here completely ignorant, many of them illiterate, with no understanding of the political process, of what democracy meant. Yet they weren’t asked any questions — they were just given the vote. Meanwhile, blacks were being denied the vote. Even where free blacks could vote, the vote was being withdrawn. It was withdrawn in Tennessee in 1834, in North Carolina in 1835. We need to make these connections.

The same thing is true in South Africa. You would think that there was nothing in South Africa before white people arrived. But they didn’t make that gold, they didn’t make those diamonds. Indeed, they didn’t mine those diamonds — blacks mined them. All whites did was to benefit from the toil of blacks. But they don’t know enough of their own history, or they refuse to confront their history, to recognize how in any civilization the various ethnic, religious, and racial groups play a part in the development of that civilization.

SE: What about the Civil War? How did those four years shape the expectations of blacks like George Washington Williams, who ran away to fight at age 14?

JHF: The war changed the expectations of an entire generation. During the war, blacks were discriminated against in pay. White privates got $13 a month; black privates got $10 a month — for doing the same thing. Black privates began to refuse to take the money; they laid down their arms and said, “You don’t seem ready for us to fight You need it more than we do. Keep it.” Some were court-martialed, but they stuck to their guns. Some were shot, for refusing to take the pay.

This was a new kind of black emerging. Freedom for them meant freedom and equality.

At the end of the war, the former Confederate states thought they could settle down to live the way they had always lived — where no blacks were enfranchised, no blacks had anything. Whites came back to power and passed laws limiting very severely the movement of blacks, their work opportunities — disenfranchising them altogether.

Blacks reacted to this in a very clear, unequivocal, courageous fashion. In every Southern state, blacks held statewide conventions — they had two here in North Carolina. They drew up resolutions, protested, and reminded the nation of what they had done. In Tennessee, the Nashville Convention of Colored Men drew up a resolution saying, “We want the ballot. We believe that surely if men return from the war after years of fighting for the country, at least they should be given the ballot.” Blacks knew exactly what the score was — what they were entitled to and what they were not getting. They were quite articulate.

SE: When Sherman marched into Charleston, there was tremendous celebration. For blacks, the war meant liberation. Yet the popular mythology is that the South was destroyed by the war, laid waste. How do we reconcile these two different memories?

JHF: Quite true — but hardly surprising. After all, who wrote the history of that period? It is important to remember that former Confederates had nothing but memories, which they cherished and wept about and exaggerated. They wrote a lot of articles like “The South: The Land We Love” — stories of the war and heroism. They left out the great celebrations in the streets, the rejoicing by blacks when they won their freedom.

They also left out the fact that the demobilization of the Union Army was very, very rapid. They said, “We were occupied, we were trampled on.” In fact, a million men were mustered out within less than a year. There were very few soldiers left — certainly not enough to maintain anything like occupation. By 1866 the best that the United States government could do was to man the regular military installations in the South like Fort Sumter. Soldiers were not striding in the streets.

There were more blacks in the army at the end, and the Confederates interpreted that as a deliberate effort to humiliate them. It wasn’t that at all. Blacks simply weren’t mustered out as rapidly because they didn’t have anywhere to go, the way the whites did.

Meanwhile, the former Confederate licked his wounds and looked back on his glorious memories. So the North began to say, “Well, if this is what makes you happy, we’ll let you write it the way you want. Just let us come down and manufacture these textiles and make these cigarettes. Making money is what makes us happy. We don’t care what you do with your Negroes and your memories.”

That’s the kind of sentiment you had after the war. And that’s the way this history was distorted — almost primitively so. It got into movies like The Birth of a Nation and became popular and respectable.

SE: When talk turns to the Civil War, the emphasis often seems to be on the word “civil.” People seem to forget that it was a war, an incredibly bloody war full of terrible carnage.

JHF: It was very, very bloody. I have no doubt that the carnage was a great trauma for the participants on both sides. This is one of the reasons why the vanquished side, suffering as it did, tended to live in the past They felt that the past was about all they had.

This also explains the continuing fascination with the war. It was so bloody and fratricidal. There has never been anything like it, before or since. It’s the only real war, real fighting we’ve had in this country — except for the Revolution, and that was not really on the scale of the Civil War.

The fascination with the war is unbelievable. Look at the Civil War Round Tables all over the United States. What else except the Civil War would make a lawyer and a doctor and a merchant close their businesses to go study something like the Gettysburg battlefield? They do it all the time. I can’t understand it — there are carloads, trainloads, busloads of people who go and walk on the battlefields.

I was in Gettysburg once to read the Gettysburg Address along with Ed Morgan, a friend of mine from graduate school who is now Sterling Professor of History at Yale. Neither Ed nor I knows very much about the intricacies of the Civil War battles. Yet there we were on these buses, surrounded by Round Table people from all over the United States.

This particular year, we were following Lee’s retreat to the Potomac, which didn’t mean a thing to me. We would ride the bus for maybe half a mile, and we’d get out, and the military historian from Gettysburg would explain the action at that point. It was raining, and we would slush through the mud to watch him point out that this particular battalion was here, this regiment was there.

Someone asked him, “Where was the Seventh Iowa Regiment at that time?” The historian pointed and said, “Over by that tree,” just as casually as if he were pointing to that book on the table. Ed Morgan looked at me, and I looked at him, and he said, “What are we doing here?” Unbelievable, it’s unbelievable.

You don’t have a similar reaction in Europe, for example. In my travels through Europe, I’ve never heard anybody say, “Would you like to go to see the Ardennes?” Of course, this country has more than its share of admiration for all things military. After all, what’s the most powerful lobby in the United States? Probably the National Rifle Association. There is this great fascination with arms and everything that relates to arms.

SE: Let’s talk for a moment about the tensions among Confederate whites during the war. We are always told that Southern whites rose as one to fight the Yankee invaders. Is that true?

JHF: No. There were many tensions among Southern whites. Many Southerners went North to school, to travel, to go shopping, and they frequently married Northerners. Northerners like the Brown Brothers banking firm had businesses in the South and owned property in the South. Many business people in New York were very much opposed to the war because of their economic interests.

When the war came, despite the fact that you had what I would call an “absence of free speech” in the South, there were those in every community who were opposed to the war. They couldn’t oppose it openly, because it was not the healthy thing to do, but there was opposition. You see it in the books, in the secession conventions and so forth. I think there was much more than was openly expressed.

This residue of opposition lingered. Things that looked so romantic in the spring of 1861 ceased to be romantic as the war progressed. You began to run out of supplies. Those lovely boots which your servant polished for you in ’61 began to wear out in ’62. Your whole perspective about the war began to change.

Women also had serious questions about their husbands going off to fight in some other part of the country. They felt deserted by their men, and they wrote marvelous letters. Imagine being on the front and getting a letter from your wife or your sister that says, “What are you doing there when we’re in danger here? Why do you go to Virginia to fight and leave us exposed here in Alabama? The Yankees could reach us any day.” That would really make you stop and think. That helps explain desertion in the Confederate Army.

The Confederacy was also tom by the same states’ rights theory that Southern states developed in arguing against the North before the war. Southern states were just as anti-central government in 1862 as they were in the 1850s. It didn’t make any difference to them whether it was Washington or Richmond — they didn’t like it, and they fought it. Leaders like Governor Brown of Georgia told the Confederacy, “You can’t impose this on us! I’m not sending you anything.” So the states’ rights sentiment helped undo the South during the Civil War.

SE: But states’ rights is always presented as the factor that united poor white farmers and rich white planters.

JHF: Farmers resented the fact that planters could receive an exemption from fighting if they had a plantation of a certain size or were responsible for a certain number of slaves. Now that’s sort of strange. After all, a sensitive Southern gentleman shouldn’t have to be persuaded to go to war to fight for his honor — yet here they were hiding behind exemptions.

Gradually, you began to hear that phrase, “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” There was a strain between classes of white people in the South. The workers, the landless or small farmers felt they were doing more than their share, and that strain contributed to desertion and all kinds of morale problems in the Confederate forces.

SE: Is there any possibility of “reconstructing” the past so that Southern whites can realize that there was a loyal opposition to the war — that there is an alternative history, if you will?

JHF: It’s an interesting proposition. The history has been so distorted that it would take some doing. There are books which touch on this, but I don’t think they do what you’re suggesting — reversing the whole perspective and looking at the war from the point of view of the opposition. I don’t think that’s ever been done fully and adequately. It would be a great challenge. I don’t know who would do it. But it can be done.

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.