This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

The Civil War was, as Robert Penn Warren has written, “the greatest single event in our history” — not just for the South, but for the nation as a whole. In four years, it affected every facet of American life, transforming the way we live and the way we see ourselves. It fostered a national banking system and national currency, created the national debt and the federal income tax, and ushered in an age of robber barons and big business. It left 700,000 Americans dead — more than every other war in our history combined. And in the process it abolished slavery and plunged the South into a chronic poverty from which it has yet to recover.

In a sense, the Civil War defined the South we know today. The Confederate States of America lost a war — something the rest of the nation did not face until Vietnam — and the psychological pain of that defeat continues to haunt the region like the ghost of Robert E. Lee. “Only at the moment when Lee handed Grant his sword was the Confederacy born,” observed Warren. “Or to state matters another way, in the moment of death the Confederacy entered upon its immortality.”

One hundred and twenty-five years have passed since that April morning at Appomattox, but nostalgia for the “Lost Cause” lingers on. Every year, millions of people tramp across Civil War battlegrounds. Thousands gather to re-enact some of the bloodiest days in American history — at Antietam and Gettysburg, at Shiloh and Vicksburg and Bull Run. They fly Confederate flags and visit Confederate graves and listen to Hank Williams Jr. sing “The South Will Rise Again.”

When we set out to prepare this special section of Southern Exposure on the lingering legacy of the Civil War, we wanted to take a closer look at the meaning of such nostalgia. Given that the war freed four million Southerners from chattel slavery, is it appropriate to say that “the South” lost? Should not defeat be assigned to some more specific group of people within the South?

The South was a diverse and divided land at the start of the war. In 1860 the top 5 percent of free white men owned 53 percent of the wealth, while the bottom half owned only 1 percent. What’s more, one-third of all Southerners were slaves, and as such they were actually considered part of that wealth, stripped of all rights and held in bondage on plantations.

Wealthy white planters went to war to protect that property, launching a last, desperate attempt to preserve slavery and turn back the rising dominance of Northern industry. This, then, is “the South” that lost the war, the South of most Civil War histories — the rich slaveowners and their ill-fated political and economic agenda.

In reality, there were several “Souths” in 1860, and the Civil War was actually several wars. The story of the planter’s Civil War has been told and retold for over a century. Within the region, however, the war sparked a far-reaching social revolution that changed the status of women, slaves, and landless whites. It also ignited a violent class struggle over who would control the political economy and culture of the South. We are concerned primarily with this Civil War — the war within — and its continued resonance in the contemporary South.

As historians Michael Fitzgerald and Wayne Durrill point out in their stories in this section, many poor white Southerners did not want to break with the Union to defend the property of their rich neighbors. When white men in Tennessee went to the polls in 1861 to cast ballots on secession, 104,913 voted yes and 47,238 voted no. In Virginia, the bastion of plantation politics, the vote was 128,884 to 32,134.

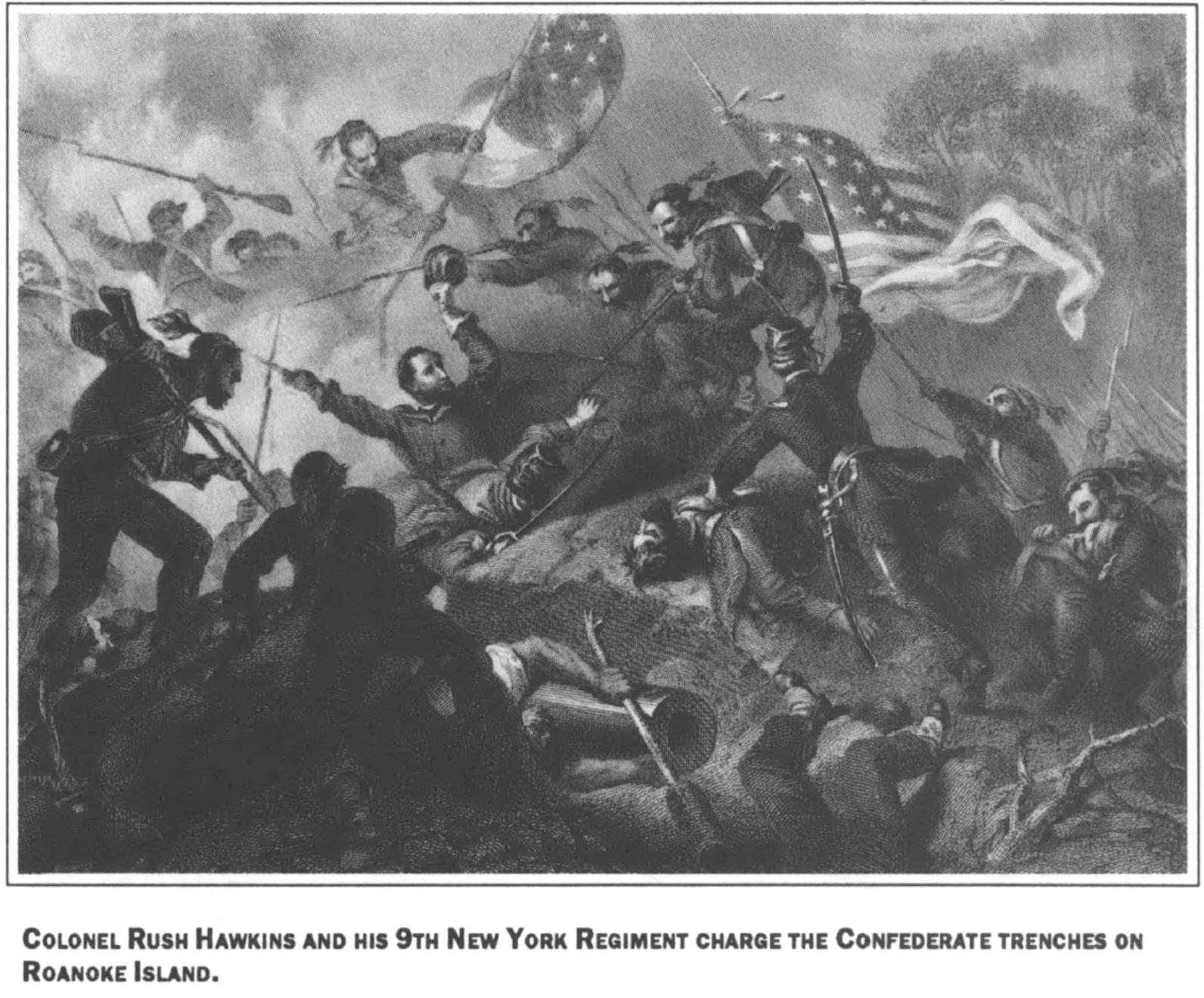

After fighting broke out, many Southern whites took up arms against the Confederacy. From the Appalachians of West Virginia to the Ozarks of Arkansas, upcountry farmers and workers waged a bloody guerrilla war for control of their land and labor. As David Cecelski recounts (“A Thousand Aspirations”), they were soon joined by thousands of blacks who crossed Union lines into freedom.

The hardship of war gradually took its toll, and dissatisfaction began to spread. The poor were hit the hardest. In 1862, Southern wages rose 55 percent, while prices soared by 300 percent.

Southern women, watching their children go hungry, took to the streets in protest. In the spring of 1863, bread riots erupted in more than a dozen Southern cities from Richmond to Mobile. Women armed with knives and revolvers raided shops and supply depots for food.

At the largest riot in Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, several hundred women marched to chants of “Bread! Bread! Our children are starving while the rich roll in the wealth!” They were driven away only when President Jefferson Davis himself threatened to have soldiers open fire on them. After the rioters dispersed, Confederate authorities forbid newspapers to make any mention of the revolt.

This is a war we seldom hear about — a war not between North and South, but between rich and poor. Instead, we are treated to time-worn tales of scrappy Rebel boys fighting to defend home and hearth from the invading Yankee hoards. Such a focus diverts attention from the internal Southern struggle, conveniently placing the blame on “outside interests.”

The myth of this noble “Lost Cause” emerged in the years of Reconstruction following the war, as Jefferson Davis and other former Confederates retired to write long literary justifications of their struggle to maintain slavery. When wealthy whites returned to power in the South, they took the vote away from blacks and landless whites and enshrined their war stories as official doctrine. Historian Lawrence Powell provides an account of how white elites in New Orleans invented a “glorious past” and literally set it in stone, provoking heated battles that continue to this day.

Such battles remind us that the internal conflicts unleashed by the Civil War are not over. From the Confederate flags waved at Klan rallies to the one that flies above the state capitol of Alabama, the history of those murderous years lives on, distorted beyond recognition. As historian Eric Foner has suggested, we must re-examine our misremembered past if we hope to avoid a misguided future.

“The age of the Civil War is the period of our past most relevant to the contemporary concerns of American society,” Foner says. “By looking again at the Civil War, we may gain insight into the choices facing our own time.”

Tags

Robert Hinton

Robert Hinton is a PhD. candidate in history at Yale University. His dissertation, “Cotton Culture on the Tar River: The Politics of Agricultural Labor in the Coastal Plain of North Carolina, 1862-1902,” is in progress. (1990)

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.