This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

Sumter County, S.C. — Between the logging trucks and the endless stream of toxic waste trucks, Highway 261 stays in a perpetual state of disrepair these days.

The logging trucks are a recent phenomenon, the legacy of the bizarre swath of destruction that Hurricane Hugo left across the state last fall. The acres of snapped pine trees seem a bleak metaphor for the economic depression of the area. Driving through the county, you pass destroyed mobile homes and farmhouses with plastic patches on unrepaired roofs. Folks say federal disaster relief has been too little, too late.

But the toxic waste trucks have been a fact of life here for more than a decade. From his small woodframe house in an open field off the highway, the Reverend J. B. Hodge watches the huge tarp-covered dumptrucks rumble by — 50 of them a day, three-quarters with out-of-state license plates. At night 20 or more trucks line up outside the gate to the GSX Chemical Services hazardous waste landfill a half mile down the road.

Standing at his back door, the purposeful, rotund minister pointed out the line of trees a few hundred yards away where the “No Trespassing” signs begin. The landfill contains three billion pounds of carcinogens and poisons buried 200 yards from the shores of Lake Marion, making it the second-largest toxic waste dump in the Southeast. It also sits atop four underground rivers, one of which supplies drinking water to much of the state. If the dump opened today, federal regulations would prohibit such a proximity to wetlands.

Unlike most of the 700 or so people in Rimini, the community closest to the dump, Hodge is outspoken about his opposition to GSX. He recounts tale after tale of neighbors, mostly children, who have suffered health problems they believe are related to contamination from the dump. Their fears were heightened when a study of seven children turned up toxic chemicals in their blood.

In 1986, the same year the blood studies were done, GSX found toxins in three aquifers beneath the 279-acre dump. The company insists the landfill is not to blame, but state and federal agencies have yet to locate the source of the contaminated groundwater.

“I don’t like what’s happening, what it’s done to the people in the area,” said Hodge. “I always tell my boys that if people start dyin’ they should pack up and get going — but just make sure that the place you go to don’t have no dump.”

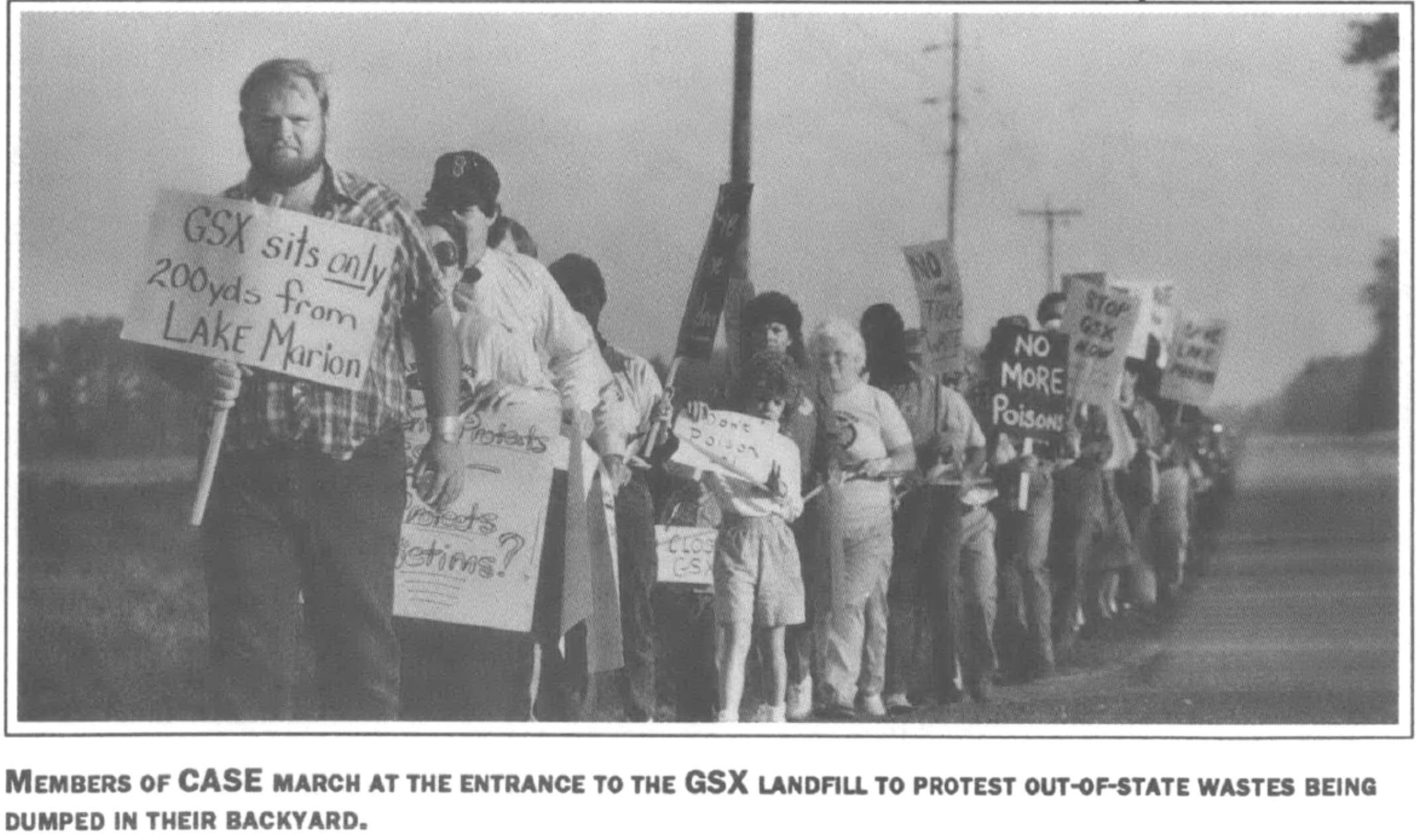

Angered by the lack of action, Hodge and thousands of Sumter County residents have organized their own grassroots group called Citizens Asking for a Safe Environment (CASE). Members want the state to curb the amount of waste that GSX can dump at the site and to phase out all toxic waste landfills in South Carolina.

Amazingly, supporters in the state legislature say measures proposed by CASE have a good chance of passing. In a state where the words “crazy” and “environmentalist” are often uttered in the same breath, CASE has been remarkably successful. In its first five years it has helped expose the devastating public health consequences of lax environmental regulation in South Carolina. Along the way, it has uncovered a trail of greed and corruption that leads to the highest levels of state government.

Blood and Poison

The Reverend Hodge first became concerned about GSX after his 1986 survey found 50 cases of unexplained health problems that Rimini residents linked to the dump. Several people reported their hair coming out in swatches. Some children had rashes, sores that wouldn’t heal. Others were listless; one little boy was so tired he could only sit and watch while his friends played at recess.

With the support of CASE, Hodge rounded up 10 children and five adults with recurring ailments and took them to the Medical University of South Carolina for examinations. When they arrived at the state clinic, they were surprised to see TV crews waiting. They were also surprised when doctors performed only rapid, perfunctory physicals—without any blood tests.

“They just went through the motions like a show and then said, ‘Don’t worry about anything, folks,’” Hodge recalled. “I feel like it was planned.”

His suspicions seemed confirmed when CASE obtained a letter to the president of the Medical University from a top official at the state Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC), the agency responsible for regulating GSX. The letter — which was sent prior to the exams — warned that “health examinations are not a useful approach and at best will be misleading.”

Dr. Jim Ingram, a private physician and a member of CASE, was outraged by the DHEC intervention and the handling of the physicals. “If they were going to do exams they should have looked at whether the people were poisoned,” he said. “They should have done the blood work, and without that they shouldn’t have said the exams were reassuring.”

Disappointed, CASE secured Medicaid coverage to pay an independent lab to do comprehensive work-ups for seven of the children. Six of the seven blood tests revealed high levels of the organic solvent toluene, which depresses the central nervous system. The blood samples also contained high levels of cancer-causing trichloroethane (TCE) and DDT, a deadly pesticide that was banned long before the children were born.

All of the chemicals in the children’s blood are also found in the GSX landfill. Toluene and TCE were among the contaminants found in groundwater at the site that same year.

Dr. Paul Epstein, an occupational and environmental health specialist at the University of Illinois School of Public Health, interpreted the results for CASE. He recommended “an immediate suspension of operations” at the GSX facility and independent medical testing of local residents and GSX employees.

Four years later DHEC has taken no action other than to criticize CASE for protecting the identities of the children tested and to impugn the competence of the laboratory that conducted the tests.

Sam Moore, a GSX spokesman, also dismissed the suggestion that the cursory exams at the state university were incomplete. “If there was a real problem here it could be solved before dark,” he said. “Do you really believe that two state agencies would conspire to defraud citizens and defend industry? If that’s the case we should put environmental pollution aside and work on the pollution of our morals.”

The technical arguments and official reassurances aren’t much comfort to Ann Clark, a Rimini resident who lives only a mile from the dump. The lab tests found toxins in the blood of her nine-year-old son, Mandrake. “I didn’t believe the rumors until I took Mandrake to the doctor,” said Clark, a home health nurse.

Clark also suspects the dump could have something to do with why her infant son breaks out in so many rashes and why her five-year-old was born with a defective hand. “I feel like my children are victims,” she said. “We’ve considered moving, but we can’t afford it.”

Still Alive

Unlike Clark, many residents of the small, economically depressed communities of Pinewood and Rimini are unwilling to talk to reporters. Jobs are scarce, and GSX is the largest employer around. The company has been generous with local folks, hauling dirt for free and sponsoring the annual Possum Trot.

In Pinewood, the clerk at Big A Auto Parts refused to comment on the landfill: “They do a lot of business around here.” Next door at the Gulf Station an attendant shrugged: “You gotta put the stuff somewhere. GSX gives money. They’ve done a lot for the town.”

D.P. Elliott, who runs his own auto parts store, crawled out from under the hood of a car to put in a good word for the landfill. His father, Dargon, leases the dump site to GSX.

“I like it,” Elliott said. “I make my living off it. No one says the good things about GSX. I don’t believe that stuff about it leaking. I live right next to it, I drink the water and I’m still alive!”

But the GSX largess has not bought everyone. A recent survey by two psychologists revealed that 90 percent of local residents believe the waste dump will cause health problems in the future.

“There’d be something wrong with us if we didn’t worry about it,” said Mark Smith, the cashier at Sym’s Grocery. “We know it’s going to leak some day. There hasn’t been a landfill that hasn’t leaked, has there?” Smith said he doesn’t talk much about his concerns at home, since two of his brothers work for GSX.

Unusual Allies

Despite the company’s influence among local residents, CASE has grown to over 7,000 members, most of them educated, middle-class residents of Sumter, nearly 20 miles from the landfill. It has also gained the support of some influential people in state government, including Senator Phil Leventis of Sumter.

“To an extent, the watershed of citizen involvement on this issue was bound to happen given South Carolina’s history as a dumping ground,” Leventis said. “It has become a symbolic issue.”

Joe McElveen, state representative from Sumter, said South Carolina residents are tired of being “the nation’s pay toilet.” The state is home to the massive Savannah River Nuclear Plant, a low-level nuclear waste dump, two hazardous waste incinerators, and an infectious waste dump—which all cater primarily to out-of-state military and industrial interests.

According to federal statistics, South Carolina imports more than three times as much hazardous waste as it exports to other states. The sheer volume has taken the state beyond the familiar “not-in-my-back-yard” complaints, creating a groundswell of popular opposition to hazardous and radioactive wastes.

CASE has played a pivotal role in organizing that opposition and focusing it on realistic goals. The group’s proposal to curb dumping at GSX is being taken seriously in the statehouse, a testament to CASE’S success in forcing legislators to consider environmental concerns. As an editorial in the Sumter Item observed, “In an election year no legislator is willing to risk the consequences of voting against curbs on toxic waste.”

Even Governor Carroll Campbell jumped on board the anti-waste bandwagon last year by declaring a highly publicized ban on waste imports from states that lack their own toxic landfills. It was a short ride. When other states promised to submit plans for building their own facilities, the governor quietly rescinded the ban and signed a regional dumping pact with Alabama, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

Campbell, a Republican running for re-election, continues to talk about controlling toxics, but has yet to act on his words. Political observers say he is determined not to let Democrats claim the environmental issue as their own.

Other Republicans are also joining the anti-waste chorus, giving CASE some unusual allies. Ken Corbett, a Republican state senator from Myrtle Beach, made the GSX landfill a major issue in his campaign. Myrtle Beach gets its drinking water from an aquifer that runs under the landfill.

“All the experts agree there will be a leak,” Corbett said. “There’s not enough money in the world to clean up and reclaim the wetlands of central South Carolina. We are slowly but surely dismantling the infrastructure that caters to out-of-state dumping.”

Another measure of how far the environment has moved into the mainstream is the support of Pete Gustafson, lobbyist for the South Carolina Farm Bureau, which has historically resisted land-use regulation. “We’d like to see the landfill closed,” said Gustafson. “Farmers are concerned about what may happen to that lake. The ultimate decision on this will be made by the public.”

Fast-Food Lobbying

Janet Lynam and Carol Boykin, the president and vice-president of CASE, try to make the hour drive to Columbia twice a week when the legislature is in session. The two homemakers put on their “lobbying suits,” arm themselves with expert studies on violations at GSX, and leave their husbands notes telling them to pick up fast food for dinner.

Although Lynam and Boykin have the support of most voters and an increasing number of lawmakers, they still face an uphill battle when they enter the carpeted enclave at the statehouse. GSX employs nine lobbyists, more than any other interest group roaming the legislature.

On this particular day, Lynam and Boykin approached John Rogers, the speaker pro tempore of the House who opposed the CASE proposal to phase out the GSX landfill. Buttonholed in a hallway, Rogers nervously explained that North Carolina was thinking about opening a hazardous waste dump across the border from his district. “I don’t want to do anything to encourage them,” Rogers said.

Three times during his five-minute conversation with the women, Rogers glanced hopefully at passing colleagues. “Are you looking for me?” he shouted.

Finally, he excused himself and hurried into his office. “Look!” Lynam gasped, spotting a GSX lobbyist “There’s Ken Kinard sitting in there waiting for him!”

Boykin and Lynam headed for the House Ethics Committee to browse through the files. Rogers’ campaign reports showed that Kinard spent “more than $100” entertaining him at one conference in late 1987 and “more than $200” at two others. Rogers reported he did not know the total sums. Rogers had also accepted a $200 campaign contribution from GSX in 1985.

Such gifts pale in comparison to John Felder, a Republican representative who led the opposition to CASE’S legislation. Felder received $1,100 in contributions from GSX and $800 from an association of textile firms that dump their wastes at the landfill.

Ethics rules require lawmakers to report all gifts of $100 or more, but sources in the legislature have told Boykin that thousands in cash are often passed under the table. GSX reported paying about $100,000 in salaries to one full-time and eight part-time lobbyists last year, plus $50,000 in “expenses.”

“I used to believe that government agencies and the legislature were protecting the public,” said Boykin. “But that’s not true. Mostly what’s protected is industry, because people are not as powerful as industry. Lobbyists wine and dine legislators and give money for their campaigns. How are citizens going to fight that? The average person puts in a 40- to 60-hour week and is busy trying to live his life.”

According to Senator Leventis, the profit margins for waste dealers is second only to the illicit drug industry. “An accountant friend of mine estimated that the GSX landfill generated a $16 million profit each year, which mostly went to pay debts it has with Laidlaw, its parent company in Canada,” the senator said. “Even the profits that stay in South Carolina are plowed into lobbying efforts to keep the dump legal instead of research and development on waste reduction and recycling.”

Ethics laws in South Carolina are among the loosest in the nation, and officials from the state Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) often wind up on the payroll of the company they are supposed to regulate. “Every site manager at GSX is a former DHEC official,” complained Leventis. “Our laws are so spongy it’s outrageous.”

The current GSX president, William Stilwell, was in charge of engineering at DHEC when the agency first considered whether to issue the landfill a permit to dump. Stilwell went to work for GSX three days before the permit was granted.

At he Epicenter

When the GSX dump first opened in 1978, the state did almost nothing to monitor its operation. There was no state inspector at the dump, and officials rarely tested waste coming in.

Since then regulations have tightened, and GSX has become more sophisticated. Even its opponents agree that the landfill employs “state-of-the-art” technology. Visitors to the dump are treated to a slick promotional slide show. “Welcome,” croons the narrator over a swell of upbeat music, “to the next generation in waste management.” The show goes on to tout GSX, which runs numerous facilities across the South, as “the third-largest waste management company in North America.”

Sam Moore, the GSX engineer in charge of public relations, has been with the company since it opened the landfill. “Waste slipped up on all of us in industry,” he said, using a break-apart model to illustrate how the landfill works. Each “fill” — roughly the size of a football stadium — contains a

thick plastic liner over five feet of impermeable clay. Since 1984 the company has employed a “leak-detection” system with a second plastic and clay liner beneath the first and a pumping system designed to detect any toxins that breach the upper liner.

For 15 to 20 years after each fill is sealed, GSX must pump out all the “leachate” — contaminated water that was trapped in the waste — until the fill is dry. “The EPA has learned from us, they have adopted our standards,” Moore said.

Unfortunately, Section I of the waste dump, the part closest to Lake Marion, was filled before the company started using a second liner and leak-detection system in 1984. When asked about that section, Moore grew more sober. “I live here in Sumter County,” he said, “and I will never feel comfortable with Section I until we can no longer get any leachate out of it. A dry landfill doesn’t leak.”

And what happens when the upper liners that keep rainwater out of the fill degrade in an estimated 25 to 50 years? Moore insisted that the slope of the site will ensure that water will run off instead of soaking into the buried waste. “What if there’s an earthquake?” he quipped, throwing up his hands. “There are no guarantees in life.”

In fact, the GSX landfill lies in an area that is prone to earthquakes. Geological surveys put the epicenter of one 1972 quake almost directly under the land where the GSX landfill now stands. When James Watt took over the Interior Department eight years later, however, federal officials “resited” the epicenter about 15 miles from the dump.

In the first two months of this year, Sumter County experienced four minor earthquakes measuring more than two on the Richter Scale. State seismology experts predict that a “moderate” quake registering five or more will hit the area within 50 years.

Few residents in Pinewood or Rimini have the time or education to interpret geological surveys or environmental risk assessments. Besides, even if cancer-causing toxins from the landfill are already seeping into local water supplies, it could be 20 years or more before they cause those who live near the GSX dump to fall ill or die.

Ann Clark still worries about her sons. But there’s no money in her budget for luxuries like bottled water. She has little time or money to lend to CASE’S efforts, but she supports them.

“I hope things get better,” Clark said. “There’s no room for worse, especially for the children. They’re our future, and if things don’t change, there’s not going to be nothing left here for them.”

Tags

Sandy Smith-Nonini

Sandy Smith-Nonini is an adjunct assistant professor of medical anthropology at the University of North Carolina Chapel-Hill and a former investigative reporter for Southern Exposure, the print forerunner to Facing South.