This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

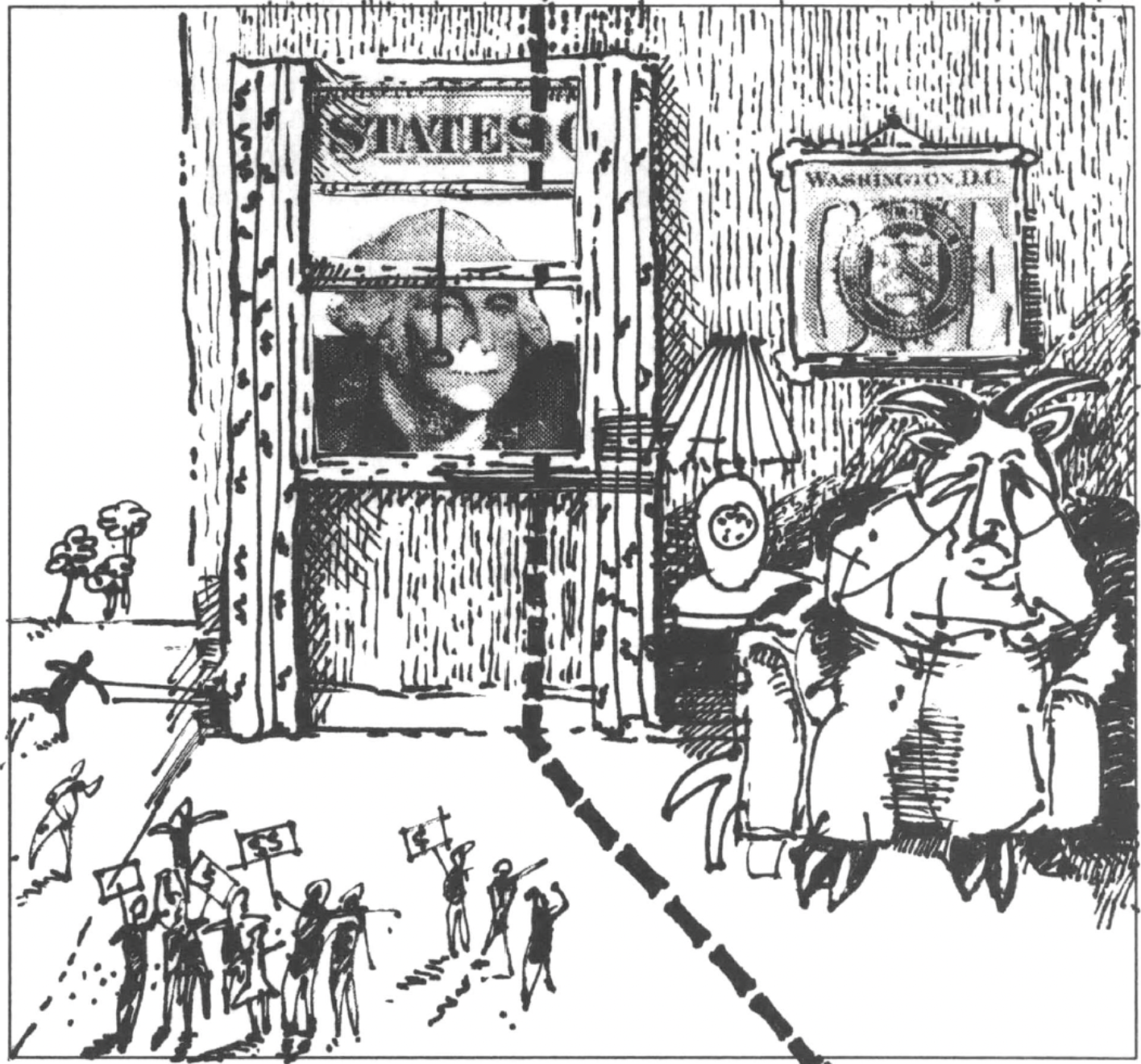

Editor’s note: One hundred years ago — in December 1889 — delegates of the Farmers Alliance and the Knights of Labor met in St. Louis to forge a union between rural and industrial workers. With its far-flung system of cooperatives and grassroots education, the new movement had already attracted hundreds of thousands of recruits. What made this convention historic, however, was the report of its Monetary Committee, an audacious program for financial reform authored by Texas leader Charles Macune.

Macune proposed creating “subtreasuries” where farmers could store their crops and borrow against them at low interest — in other words, a system that harnessed the monetary authority of the nation on behalf of its citizens.

Last December — a century after Macune unveiled his plan — two dozen leaders of farm, labor, and civic groups convened in St. Louis to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Populist convention and discuss a contemporary program for financial reform. Nearly all the participants came to the meeting through their involvement in the Financial Democracy Campaign, a grassroots effort promoting fair and sensible solutions to the collapse of the savings and loan industry.

Among the speakers was Lawrence Goodwyn, professor of history at Duke University and author Democratic Promise, the landmark history of the Populist movement. A shortened version of his talk follows.

In my profession, it is more consoling to develop a long angle of vision. If you focus on just one generation, you may not find enough to warm the spirit. Better to have four or five hundred years in your gaze and be judiciously selective within that period.

All kidding aside, certain rhythms become very clear over the long view. First, in all human societies, almost all the people have substantial grievances. Second, despite this universal sense of injustice and injury, the number of large-scale social movements is very small. In our country, the CIO mobilization of the ’30s and the Agrarian movement of the 1890s — Populism — are the only movements after the Revolution that achieved genuine scale and internal organization.

How do we explain this fundamental disjunction between the widespread existence of grievance and the very rare occasions of collective assertion? The answer is deceptively simple: Large-scale democratic movements happen only when they’re organized. And they’re not organized more often because the entire culture of a society is arrayed against the idea of large-scale collective assertion.

The primary task of revolutionaries when they come to power is to create a society in which they can put down their guns. The first step is to take control of the past and use it to justify the revolution. The second step is to create a culture in which unsanctioned ideas are difficult if not impossible to have — a culture, in short, in which it becomes difficult for people to imagine structural change. Social space evaporates and society becomes rigid. Of course, those in power don’t view it this way; they call the result “stability.”

Future historians will look back and see much more of this rigidity in the societies of the 20th century than we ourselves can summon the poise to see. They will see highly stratified societies characterized by deep brooding anxieties, enormous systems of centralized bureaucracy atop an economic structure of large-scale production. And they will say, “What a narrow century the 20th century was. It was the least creative political century of the last three.”

Publicly, people announced that they lived in the best society in the world. But privately they said, “You can’t fight city hall . . . the rich get richer and the poor get poorer . . . all politicians sell out,” or (with their teeth considerably more grimly set when they say it), “You can’t fight the Communist Party . . . the Party gets all the goods . . . the Party is corrupt.”

Future cultural historians will say that 20th-century people wore social masks to conceal their private anxiety. The practical effect of this alienation is that we can no longer conceptualize democratic social relations: Can we conceptualize a democratic marriage? A democratic workplace? A democratic system of money, credit, and exchange at the heart of all our material relations, operating not for the benefit of bankers but for the benefit of society? Future historians will have to conclude that these concepts were not politically admissible within the received culture of American democracy.

Who Stole the Goods?

So, up until now, it’s been a very narrow century, politically speaking. What do we do about that? Well, 112 years ago, a small group of people, not very different from the people in this room, met together. At that first meeting, they had seven people. Despite the fact that they had a number of deep economic anxieties, they had a sense of self and they talked to each other about doing something about their plight. They created what they called the Farmers’ Alliance.

The opportunity they possessed was that they could talk about the society and the system of finance. There was an existing literature called the Greenback doctrine that encouraged people to think structurally about money and exchange relations. Nevertheless, they had a recruiting problem. Imagine that this is sort of a big kitchen that we’re in today, and we’re sitting around the kitchen table analyzing American society. We’re grumbling about the Republicans and Democrats. We could say such things as, “Well, there are three institutions in America that house American workers — the Roman Catholic Church, the black church, and the American trade union movement. Those three institutions, plus us, are victimized by structures of hierarchy in the United States that systematically transfer income from the very poorest to the very richest.”

We may tell ourselves that these three institutions are not internally organized to do anything about it. They’re not quite sure who stole the goods. It’s sort of awesome to say that both major parties or that something called Wall Street stole the goods. We wouldn’t want to speculate that that great reform institution, the Federal Reserve System — a product of Populist agitation but certainly not anything the Populists wanted — now persists as an instrument of stealing the goods.

We can’t accuse people who donate money to the Episcopal Church, pay their taxes, and wear proper top hats and coats of stealing the goods. We don’t want to make this indictment because it’s too sweeping. It breaks the paradigm in which we are trained to think. It’s not culturally admissible discussion for dinner tables or even kitchen tables. In fact, to the extent that we can develop a level of candor and analysis about our society, then two contradictory things occur. Number one, we’re enhanced by the sheer authenticity of the conversation. Second, we’re depressed by the problem of how we are going to persuade those people out there — otherwise known as the Americans — to think seriously about the state of the Republic.

We have a recruiting problem. Our situation is perfectly analogous to what the Farmers’ Alliance faced 112 years ago. They looked for a recruiting device and they found one. The collective problem of farmers was access to credit they could afford. They were paying 30, 40, 60, 80 percent — sounds unbelievable, but you might be paying more for credit today than you know; we may have breached the Biblical level of usury some time ago.

The Alliance started co-ops to do for the farmers collectively what they could not do individually: gain access to credit. People joined the Alliance Co-op. And the Alliance grew. In a county, there would be scores of sub-alliances of 20 to 50 people each. And each one had a lecturer who would help them analyze the world. There were 250,000 members in Texas and 140,000 in Kansas and 130,000 in North Carolina. Eventually the Alliance penetrated 42 states and recruited two million people who, in effect, developed a new way to think.

Along the way, in their struggle to get large-scale co-ops functioning, they discovered that the bankers would not cooperate. The problem of the individual farmer became the problem of the Alliance: access to credit. One of their number, Charles Macune, felt the pressure of this failure more acutely, because as spokesman for the Alliance he had made projections for people — “Join us, and collectively we’ll try to change the way we live.”

So, in the summer of 1889, brooding about the political trap he was in, brooding about the plight of the nation’s farmer, brooding about the structure of the American economic system, Macune came to the Sub-Treasury Plan — which is just as logical and humanitarian and democratic now as it was then. He thought you could mobilize the capital assets of the nation in an organized way to put them at the disposal of the nation’s people.

That is a democratic conception that is not part of contemporary debate. It is beyond our imagination. It is not on the agenda of the Democratic Party or the Republican Party. In fact, we’re in an era where those tiny pieces of the nation’s capital assets that somehow were smuggled to sectors that are not rich are slowly being shipped away. Since 1980, the lowest 20 percent of the American people in income have had a real income drop of nine percent. And the top two percent have had a real income gain of 29 percent.

We have just witnessed the largest redistribution of income in American history from the very poorest to the very richest — and there’s not a single institution of large scale in the country that says this economic fact should be at the center of public debate. Now that’s more than stability. That’s rigidity.

“They Don’t Lie”

There is another society in our time — “the East,” or what is sometimes called “actually existing socialism.” For about 40 years, since Stalin imposed this system on whole populations, an idea floated around in people’s heads over there. The idea was, “We will try to create some space where we can talk to each other and affect the world we live in. To do that, we’re going to have to combat the leading role of the Party.”

On the Baltic coast, in the 1950s and 1960s, workers in shipyards would say to each other, “We have got to create a trade union independent of the Party.” Now that was an unsanctioned idea; it was frightening even to say it out loud. They’d only say it around the kitchen table, around carefully selected brethren and sistren. And the idea would go away, because it was unsanctioned.

But then there would be another horrible accident in the shipyard, another insane adjustment of work routines, and the idea would come back, simply because it was the only idea that made any sense. “Work organized by the Party is insane, Poland is insane, our social life is insane. We’ve got to have a union free of the Party.”

Over 35 years of self-activity the world has not known about — any more than the world knew about how the Farmers’ Alliance organized Populism — the people of Poland found out how to do it. And in 1980 they did it. The single most experienced organizer in the shipyard in Gdansk, who spent 12 years organizing and going to jail and brooding about a union free of the Party, the single most credentialed worker, based on his own activity, is Lech Walesa. There’s a certain logic in history every now and then.

By its simple existence, Solidarnosc sent a wave of hope across Eastern Europe. It combated the mass resignation that was the dominant political reality of social life in those societies. And it became the nucleus of a mass movement, one of those rare moments in human history when people get back in touch with their own subjectivity. That is to say, they don’t lie in public. They say what they mean. They ‘re not trying to give speeches. They’re trying to be clear, like two people in a marriage struggling not to be political with each other but to be candid.

Because Solidarity stayed alive and because a man named Brezhnev was replaced by a man named Gorbachev, who would not put down Solidarity, the leading role of the Party is going into the dustbin of history all over Eastern Europe.

Back to 1889

Now back to our recruiting problem. What if we were to suggest to the American people that we can’t do anything about the homeless, or the crisis in the cities, or the inability of the children of (once unionized, now “de-industrialized”) workers to own a home, or America being sold to foreign creditors — we can’t do anything about any of these matters if we don’t democratize the financial system in this country? In other words, we can’t do anything until we get back to being as advanced as we were in 1889 when the subtreasury system was first introduced.

The idea will be scorned as too much. It’s not properly modest “Why, you people sound as if you’re as crazy as those people in Eastern Europe.” But if you have the long-distance view, if you say, “Give ourselves 20 years. Let’s see if we can begin the process of educating ourselves and the American people about the idea of a democratic system of money that will save what is left of the American family farm, that will pump life into the cities, that will permit the young to dream that they might own a home of their own, that might somehow begin to chip away at the culture of corruption that is now the norm in public life. . . .”

If we can do that, if we can say what we know, clearly, and endeavor to act quietly and firmly on what we say, then I think we’re living a valid political life. We may not change the world. But, then again, we might.

For a booklet on the St. Louis conference, send $2 to the Southern Finance Project, 329 Rensselaer, Charlotte, NC 28203.

Tags

Lawrence Goodwyn

Professor of history at Duke University and author of Democratic Promise, the landmark history of the Populist movement. (1990)

Larry Goodwyn teaches history at Duke University. His son, Wade, born in Austin during the family’s years with the Texas Observer, is currently a member of the Longhorn Marching Band. (1979)