Picturing Freedom

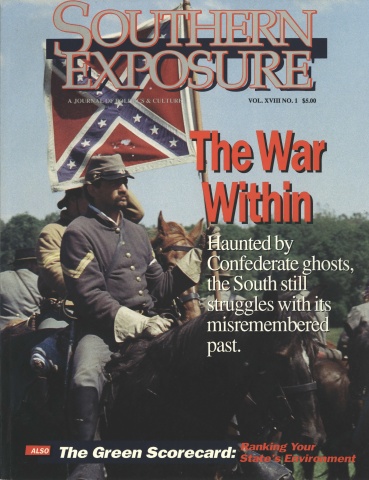

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

“There is no arguing with pictures,” wrote Harriet Beecher Stowe as she began work on Uncle Tom’s Cabin. “Everybody is impressed with them, whether they mean to be or not.”

In a society that had worked hard to repress troubling images of slavery, Stowe’s novel proved explosive. Arriving at a time when the popular illustrated press was rapidly becoming a powerful new cultural force, it appeared in serial form before it became a book.

Stowe saw herself as a “painter” with words, seeking to hold up the “peculiar institution” before her readers “in the most lifelike and graphic manner possible.” Even those who detested her message had to concede her success, when her fictional account of “Life Among the Lowly” sold an unprecedented 300,000 copies during 1852 — the equivalent of 20 million copies today. The book’s scenes of slave auctions, brutal punishments, and dramatic escapes, along with the piety of Uncle Tom, provided a storehouse of verbal pictures to inspire visual artists.

The success of her work—and the illustrations that accompanied it — also confirmed Stowe’s belief in the power of pictures. Even before the struggle for black freedom in America erupted into open war, important battles were already being fought out in popular periodicals and elite academies of art. For the images that whites used to portray African-Americans were a matter of continuous debate and considerable consequence. They reflected — but also helped to shape — public opinion in the years just before and after Emancipation.

Bad for Business

An English artist named Eyre Crowe was reading Stowe’s novel when he traveled through the South in 1853. In Richmond, Crowe visited the city’s slave sale rooms and sketched a scene that he later developed into a painting entitled Slaves Waiting for Sale — Richmond, Virginia. Five neatly dressed women and three children of varying ages sit on a bench around a rusty stove. Separated from them is a muscular fieldhand hunched slightly forward with his jaw tight in anger and his fists clenched in a silent gesture of defiance. It is significant that a foreign painter would record this attitude of protest. American artists, reluctant to depict such a threat in their midst, shied away from depicting black men capable of reflection and revolt.

One American sculptor, John Rogers, learned early in his career that representing strong and sympathetic blacks could be bad for business. A few days before the attack by John Brown and several black men on the U.S. arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in October 1859, Rogers had the idea for his Slave Auction group.

“The design is a man & his wife & two children who are standing before the desk of the auctioneer who is selling them,” Rogers wrote. “The sentiments expressed are the maternal affection of the mother and the sullen resignation of the man while the auctioneer is expressive of heartless calculation.”

When this group went on the market two weeks after the execution of John Brown, it was very well received by the abolitionist community. But, as Rogers himself remarked: “I find the times have quite headed me off, for the Slave Auction tells such a strong story that none of the stores will receive it to sell for fear of offending their Southern customers. . . . By taking a subject on which there is a divided opinion, of course, I lose half my customers.”

Despite this financial setback, John Rogers, like Eyre Crowe, gave us a strong, capable American black man. In doing so, these artists contradicted the prevalent views both of abolitionists, who tended to see slaves as dependent on them for their liberation, and of the defenders of slavery, who maintained that blacks were essentially incapable of managing without their masters.

Dawn of Liberty

While slave auctions provided one visual focus in the years after Uncle Tom’s Cabin appeared, attempts to escape from bondage provided another. The Scottish artist, John Adam Houston, painted The Fugitive Slave in 1853, and Englishman Richard Ansdell created a dramatic canvas, Hunted Slaves, in 1861. Thomas Moran, an English-born artist living in America, probably saw Ansdell’s painting when he visited London in 1861; the following year he created his own treatment of the theme, entitled The Slave Hunt.

With the outbreak of war, opportunities for escape increased, and the camps of the Union Army became the destination for hundreds of desperate and courageous black Southerners. Engravings in Harper’s Weekly frequently showed the flow of so-called “contrabands” to Union lines, and oil painters also took up the subject.

In Theodore Kaufmann’s On to Liberty, a group of women and children, bathed in the light of a metaphorical dawn, are within sight of freedom. (Perhaps the expressions on the faces of the first frightened East European families rushing to the West during 1989 can help us begin to imagine the emotions connected to such scenes.) Having traveled all night with their few personal belongings balanced on their heads, these fugitives dare not rest until they reach the American flag waving in the distance. (See illustration.)

Such dawn scenes were often actual as well as symbolic, as Eastman Johnson learned near Manassas on March 2, 1862. Through the morning mist the artist witnessed a family of four, astride a horse, dashing toward freedom. He recaptured the moment in his dramatic painting A Ride for Liberty — The Fugitive Slaves. The glint of bayonets can be seen in the distance as Union soldiers advance into battle, a clear reminder of the sacrifices being made to bring about a new dawn of liberty.

For most of the South’s African-Americans, escape from slavery was impossible. Hope for freedom lay in waiting and watching for the Stars and Stripes to arrive. Pockets of slaves near the coast, in the Sea Islands and elsewhere, welcomed liberation forces early in the war, but for most the wait seemed interminable.

The gifted New England painter Winslow Homer portrayed the tension of waiting in a little-known picture that shows a handsome black woman emerging from a cabin doorway. In the background Confederate soldiers, carrying the Stars and Bars, lead away unarmed Union captives. (This painting, lost for nearly a century, was shown on the cover of SE Vol. XII. No. 6.)

Scholars first called Homer’s oil painting At the Cabin Door, but recent research has revealed the artist’s more meaningful original title: Near Andersonville. The reference is to the Andersonville prison in southwest Georgia, the largest POW camp of the war, where some 45,000 Union soldiers were imprisoned under dismal conditions and 13,000 lost their lives. The face of Homer’s woman is grave with concern; her hands anxiously grip her apron. Dipper gourds, the traditional emblem of freedom in the Afro-American community, grow beside her door, but their promise cannot be fulfilled as yet. For the moment her would-be liberators have been captured, and she must conceal her reactions or run the risk of putting her life in jeopardy.

An article in Harper’s on September 30, 1865 makes clear just how dangerous it was for black Southerners to express their hopes over the long-awaited arrival of federal troops. The story tells of one Amy Spain in Darlington, South Carolina, who reacted to the arrival of Union soldiers by exclaiming: “Bless the Lord, the Yankees have come!” Unfortunately, the occupation was only temporary. When Sherman’s cavalrymen departed, local whites in Darlington condemned Spain to death for her disloyalty to the Confederacy. According to the illustrated article, she was hanged “to a sycamore-tree standing in front of the courthouse, underneath which stood the block from which were monthly exhibited the slave chattels.”

Amy Spain’s fate could befall the woman depicted in Near Andersonville if she reveals her disappointment. Through this isolated, stoic figure, Homer communicates the anguish of waiting for liberty long delayed.

From Slave to Soldier

From the very beginning of the war, black Southerners campaigned for the right to bear arms and participate as soldiers in the struggle for their own liberty. Both the Union and Confederate armies forbade blacks to fight in their ranks. By the summer of 1862, however, the North could no longer afford the luxury of such racism. In July Abraham Lincoln began the first draft of his historic Emancipation Proclamation which would free the slaves of disloyal masters and open the Northern armed services to Negroes. On September 22, President Lincoln announced his proclamation would be signed 100 days later, on New Year’s Day 1863, applying to all states then still in rebellion.

Reaction to the Emancipation Proclamation was felt throughout the land and filled the illustrated press. On January 24, 1863, Harper’ s published a double-page engraving by the staunch abolitionist and pioneering political cartoonist, Thomas Nast. Calling his picture Emancipation of the Negroes, January1863—The Past and the Future, Nast arrayed the past evils of slavery on the left, in contrast to the optimistic prospects of freedom on the right.

The next week Harper’s presented Alfred Waud’s Contrabands Coming into Camp in Consequence of the Proclamation. The following month the editors included a wood engraving of The Effects of the Proclamation : Freed Negroes Coming into Our Lines at Newbern, North Carolina. (See engravings.)

Even before Emancipation, Northern artists who visited the front could not help but be struck by the presence of Southern blacks arriving as refugees. The appearance of “contrabands” caused sharp debate within the Union high command, and the reactions of Yankee soldiers varied almost as much. When Winslow Homer created A Bivouac Fire on the Potomac for Harper’s on December 21, 1861, he showed a former slave dancing to the tune of a black fiddler within a circle of curious white soldiers. The picture illustrated their first encounter with the distinctive music and movements of Southern black culture.

After an outpouring of public sympathy for the first wave of contrabands, the Union Army began to find these refugees to be burdensome, and they were put to work doing menial camp tasks such as cooking meals, washing clothes, polishing boots, hauling wood, herding livestock, driving wagons, and digging trenches. Though nominally free, their situation at first was not too different from that of the slaves in Confederate camps who were being forced to prepare food and build fortifications. But later, as war casualties mounted and the difficulty of recruiting troops increased, these escaped slaves saw active service — first as scouts and pickets, then finally as armed soldiers — alongside newly enlisted blacks from the North.

The admission of black men as soldiers into the Union army provided a new subject for both the popular and the fine arts, offering not only topical material but also a metaphor for the dramatic transformations of the time. In its July 4, 1863 issue, Harper’s published three portraits taken from photographs of a Negro named Gordon. The newspaper reported: “One of these portraits represents the man as he entered our lines . . . chased as he had been for days and nights by his master with several neighbors and a pack of bloodhounds; another shows him as he underwent the surgical examination . . . his back furrowed and scarred with the traces of a whipping administered on Christmas-day last; and the third represents him in United States uniform, bearing the musket and prepared for service.”

A year later Harper’s reproduced two more images, from photos of an unnamed man, entitled The Escaped Slave and The Escaped Slave in the Union Army. The editors did not hesitate to underscore their propagandistic purpose: “We present to our readers this week . . . two sketches . . . one, the picture of a negro slave, who fled from Montgomery, Alabama, to Chattanooga, for the purpose of enlisting in the army of the Union, the other a picture of this same negro, endowed for the first time with his birth-right of freedom, and allowed the privilege dearer to him than any other — that of fighting for the nation which is hereafter pledged to protect him and his.” The article went on to praise the heroism of black regiments under fire at Fort Wagner near Charleston, Olustee near Jacksonville, and the Crater near Petersburg.

This contrasting of past and present through the rapid transformation of a black soldier receives its fullest treatment in a series of three paintings by Thomas Waterman Wood, painted in 1866 and exhibited under the title, A Bit of War History. We see first The Contraband, an escaped slave arriving at the Provost Marshall’s Office to volunteer for service. He holds his meager belongings in one hand while he tips his hat with the other and offers a timid but eager smile. In the second picture the runaway has been transformed into The Recruit, his plantation clothes replaced by a U.S. Army uniform and instead of his traveling stick, he shoulders a rifle. The man who had appeared somewhat hesitant and self-effacing as a contraband has become a proud soldier, his head and eyes lifted toward the future, his stride directed toward his duty.

In the final scene this same handsome man reappears as The Veteran. The leg he put forward as a recruit is now partially gone; his well-used gun rests against the wall behind him now, and he leans on crutches for support. With sadness in his eyes for what he has experienced, the Veteran returns home, saluting the country to which he has given such a full measure of service. African-Americans had proven their bravery as soldiers to skeptical whites.

Wood’s paintings represent a public recognition of the critical role blacks had played both in defending the Union and in fighting for their own liberty as a people. They also underscore how the war and Emancipation transformed images of blacks in American art and the popular press. No longer do African-Americans appear as slaves struggling to escape bondage. By the end of the war, white images of blacks reflect national pride in their contributions—and confidence in their ability to participate fully as free citizens.

Tags

Karen C.C. Dalton

Karen Dalton directs the Houston office of the Menil Foundation’s Image of the Black in Western Art project. She is the co-author, with Peter Wood, of Winslow Homer’s Images of Blacks: The Civil War and Reconstruction Years (University of Texas Press), selected one of the Outstanding Academic Books of 1989 by Choice Magazine. (1990)