The Palm Writer

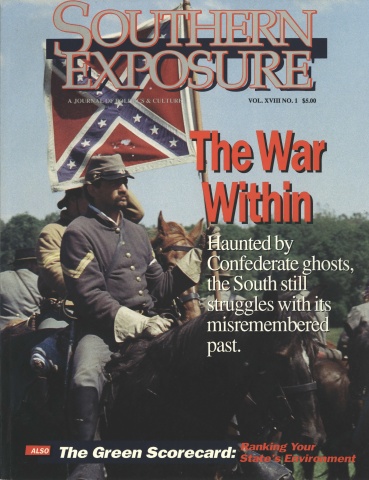

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

Old Bill’s husband, Jim Blane, had long ago painted a sign for her and nailed it to the biggest tree in the yard. The sign said: “Sister Wilhelmina — PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE.” It was bright white with red letters, like the important parts of the Bible. A giant red hand was set at the center, and the writing floated around it. She was a palm reader. Like her sign, Old Bill’s life had become rooted here, on this stretch of road between two mill towns leading to a good beach. Her house was small and celery green, situated in a like a small oasis in the August heat.

It was a Wednesday and only 9:15, but she had already seen her second customer of the day, a white lady in her late thirties, who now emerged, rather weak-kneed, from the house. Heat rippled up from the dirt driveway, where the three other ladies, all in pastel shorts sets that were new, waited, with the doors of the big blue Pontiac open and their white legs sticking out. The shrillness of their voices died down only for an instant, and that was when Jim Blane walked by with his bottle of Wild Irish Rose. Otherwise, their eyes, like those of birds of prey, stayed riveted to their friend, who stood in the shade, paying the palm reader from a heavy-looking pure white purse. When Jim Blane saw Old Bill tuck a twenty into her flowered bosom, he started humming “Amazing Grace.”

Inside, the lady had asked Old Bill the usual questions: “Will I meet a man? Will I marry soon? Will I ever bear a child?” displaying a doughy palm, with shiny sweat in its creases. When the black palm reader had touched her white hand and she had flinched, Old Bill was reminded of countless other ladies who came back summer after summer, still wanting to know the future. She had seen promising lines diminish and fade with time in those who never took chances, and though her own solvency in some way depended on these people, it was still sad to witness their inertia, so she said to this wispy little lady, “They’s three been working against you, and for an extra fifteen dollar, I can tell you who they be.” Then Old Bill described in literal detail the three who waited outside in their hot car, so the lady would not cleave any longer to these friends.

Old Bill returned to the dark interior, to the sound of many whirring fans and screeching birds in basket cages, and took herself a long, dream-drenched nap. Jim Blane, lounging in his old blue van that was up on cinderblocks around the side of the house, tipped his bottle to his lips. He could hear Old Bill laughing in her sleep.

While Old Bill lay chuckling to herself, red birds flashed in and among the mimosas like flames. Then, a melancholy wind, saturated with the smell of a far-off rainy pavement, blew in through the screen door and startled her. Many pink mimosa puffs sifted down their blossoms, and the sky grew darker and darker. Shielding his eyes to watch, Jim Blane could feel the air growing tense, like the start of a headache. There was something urgent about it. Old Bill felt a presence coming near and prepared herself to greet it, tying up her sleep-loosed hair.

A young black girl stood at the screen trying to see in. Her hair was plaited in cornrows, hanging heavily like wet wash to her shoulders, and her face was lit with such drama, Old Bill grew attentive in a way she didn’t usually have occasion to be. This life had come to hers for protection. She cut off all her fans, feeling an electrical storm coming, and crossed the room. “Yes?” she acknowledged the face at the screen.

The young girl spoke slowly, but there was desperation in her voice. “Can you read my palm, please . . . because . . .” Her voice trailed off, as if she had run out of air. A sheen of fever covered her face and her large, topaz eyes had greenish circles under them, as if she had slept poorly for many nights. She wore a summer dress with no sleeves, but her arms were somehow sunless and sickly. Her long fingers wore no rings, held no keys. She held nothing in her hands. She seemed to have come from nowhere. She smelled like carnations.

“How old you is?” Old Bill queried gruffly, but swung the door wide open. The girl, blind from the outdoors, stood stiffly and had to be led into the room.

“Fifteen,” the girl answered.

“You too young to get your palm read,” snapped Old Bill.

“But I’ll give you five dollars!” the girl began to cry.

Old Bill, sighing then, but sensing something, motioned to the girl to take a seat in a folding chair, and the girl sat down. Then Old Bill pulled up a chair for herself, and they sat knee to knee. Old Bill took both hands of the girl and turned them over to look. She sucked in her breath, but not before the girl had heard it, who now looked into Old Bill as if she might disappear.

Old Bill saw palms interwoven with such a convergence of crosses and stars, it was as if the girl had inherited the hands, already hot with use, of a prophet or a martyr. She saw a child playing, making hollyhock dolls. She saw they were a wedding party. Then she saw them all fall down. She saw a young man drowning in a lake full of glistening trout. She saw every stone, every fossil on the sandy bottom of the lake where his shoes slowly fell. She saw the girl who had come up behind him, cringe back in fear, and the rock his head had hit, that was flecked with blood. She saw a funeral procession. She saw two. She saw the girl’s wrists tied up with what looked like bandages, or ribbons.

“Lily!” Old Bill spoke the name of the young girl, for suddenly she knew it.

“Yes, ma’am?” answered the trusting girl.

“Close your eyes. I going to fix them palm!”

Lily nodded, saying, “Yes, ma’am,” once more, as if in a trance, and closed her eyes. Without the sound of her fans, Old Bill’s house had grown intensely quiet, and her caged birds slept, as if the thunder clouds darkening the horizon were a black cloth cover.

“Keep your eyes closed tight. Don’t say nothing,” Old Bill commanded, for a sudden intuition had seized her. Quickly, she got up to get something off the back porch, where the perpetual cook stove roared with fire. Behind her back, she gripped the white-hot crowbar as she made her way back to the girl.

“Hold out your hands! ” she coolly ordered, and the girl obeyed, holding out her trembling hands, whose palms still sang their tragic future. Then Old Bill touched the center of each of Lily’s palms with the blazing crowbar, screaming first in surprise, then in pain, when that fire penetrated instead her own leathery flesh.

Her palms smoked and burned, then bubbled and blistered, with a sensation of things falling from them. She felt herself float out of many shadows and enter the center of the sun, the radiant seat of love. All through Old Bill’s trial, the young girl peacefully dozed, her magic palms extended still, as if to feel a raindrop. Where the crowbar touched the young girl’s palms, Old Bill saw that the lines had become rearranged, and now hope glowed in each, like an opening rose.

Jim Blane woke with a start, hearing first the crack of thunder, then seeing only seconds later, a bolt of lightning strike at a tree in the yard. He had been dreaming of Old Bill, and in his dream she was young. Then he saw the sign he had painted smack the earth with great force where it fell. Pink mimosa blossoms fell upwards into the sky.

Next, he saw Old Bill, who was standing in front of the house, staring hard at her palms and laughing. Sadness, deep as her own fingerprints, was falling away from them. Then, seeing him see her, she held them out to him and he came running.

Tags

Susan Hankla

Susan Hankla is a poet, visual artist, and fiction writer who lives and works in Richmond, Virginia. (1990)