Look Away

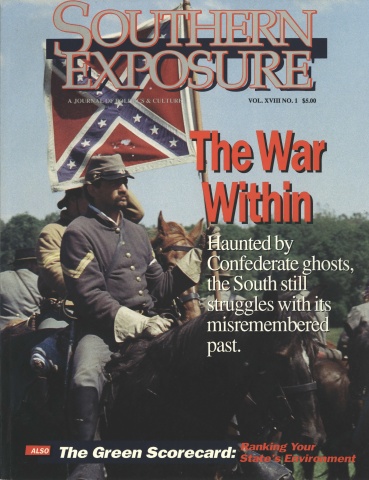

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

Durham, N.C. — It’s been two years since Alesia Keith wore the Confederate flag to school, and she’s still trying to get her job back.

Keith wore a flag handkerchief in her back pocket as she picked up junior high students along her school bus route the morning of March 11, 1988. Some of the kids had declared the day “Southern Pride Day,” and Keith wanted to show her support.

But when she pulled up in front of Chewning Junior High, “all hell done broke loose.” School officials promptly fired Keith and two other drivers and suspended 14 students. By noon, dozens of angry parents had descended on the school. More than 20 sheriff’s deputies and state troopers were called to disperse the crowd.

“You would have thought we walked in there with bazookas,” laughs Keith, a 23-year-old white woman. “I’ve never in my life seen so many law enforcement officials. And over what? A Confederate flag!”

Keith, who is suing the school board to get her job back, insists that the flag has nothing to do with racism. “It’s about heritage, not hate,” she says. “I wear it to show my pride in the South. I’m from the South, and I’m going to wear my Confederate flag, like it or not.”

Alvin Holmes doesn’t like it. On the same day Keith wore the flag to work in North Carolina, Holmes and 11 other black state legislators from Alabama faced criminal charges for trying to take down the Confederate flag that flies above the capitol dome in Montgomery.

“We had a ladder, and we tried to go over the fence and go up there and get it,” recalls Holmes. “I was just about half way over when they caught me by the legs and pulled me down and told me I was under arrest.”

Holmes and his fellow lawmakers were fined $100 each. They sued the state to remove the flag, but lost. “We feel it represents slavery and opposition to black people,” Holmes says. “It was the battle flag of the Confederate states that fought to hold black people in slavery. To fly the Confederate flag on top of the state capitol in Montgomery, Alabama is similar to flying the Nazi flag over the Knesset in Israel.”

To Holmes, the flag is more than a piece of cloth. “Every day we go to the capitol we have to look at a flag that held our foreparents in slavery. We are fighting discrimination in jobs, in bank loans, in housing, and we are fighting the Confederate flag, too. Alabama does not need old symbols that represent hate.”

A white Southerner fights to display the Confederate flag, and a black Southerner fights to take it down. One speaks of pride, the other of shame, but both feel strongly enough to resort to civil disobedience to make their point.

Such battles are as old as the flag itself. When Virginia seceded from the Union in 1861, President Lincoln sent troops to occupy Alexandria. Upon entering the city, Colonel Elmer Ellsworth of New York climbed the roof of the Marshall House hotel to remove the Confederate banner — and the enraged innkeeper, James Jackson, shot him down. Ellsworth became the first Union casualty of the Civil War.

Today, 125 years after Appomattox, the Confederate battle flag remains the most pervasive and powerful of Southern images. It is still at the center of a civil war, but this time the battles are being fought over t-shirts and license plates and baseball caps and beach towels and Klan rallies.

To many people, the flag has come to represent the worst of the South — a snarling, vicious bigotry that permeates public policy and denies blacks their full rights as human beings. Every time the flag is flown it raises haunting images of slavery and cross burnings, adding to a climate of fear and intimidation that reminds black Southerners of the all-too-real limits of their freedom.

But the flag has also been embraced by another group of Southerners — working-class whites like Keith — for whom it symbolizes nothing more complicated than home and hospitality. Many are people with little education who work two or three jobs just to make ends meet, and they cling to the flag with a fierce pride in who they are and what they have achieved. They are not bigots. Like most of us, they are simply divorced from their own history, surrounded by stereotypes that make it impossible to move beyond the lingering legacy of the Civil War.

Nikki Parkstone was 14 years old when she wore the Confederate flag to school.

“It started out at lunch one day,” she recalls. “We was just starting to get into civil rights in civics, and our teacher told us about those students expelled for wearing black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam War. To me, it sounded like the controversy over the Confederate flag. Nobody had said we couldn’t wear it, but everybody was afraid to.”

So Nikki and some friends held a “Southern Pride Day” at Chewning Junior High. Nikki sewed the flag on her jacket, and her sister Patti tied it around her leg. Both were suspended — and both successfully sued the school board to have their records cleared.

“It just meant that I’m from the South, and I’m proud to be from here,” Patti says. “It means Southern pride. Basically it means the Civil War to me — that we will fight. Even though we didn’t win the war, that we will fight.”

What did her ancestors fight for? “Their rights — their usual way of life. From what I’ve learned, the North wanted to overcome the South and make the laws, but the South wanted to make its own nation. It wasn’t right. I’d never have a slave. But that was the way they lived, and they just couldn’t imagine not having them. lean understand that. If I’m born into a home, I don’t want it taken away from me by another part of the nation.”

Nikki nodded. “I think it’s kind of special to claim to be a Southerner. I’m not saying we’re better than anyone else — we have our good points and our bad points. I just think Southern people are more polite — you know, hospitality. You think of going to New York, the Bronx, you think of getting mugged. What’s the worst that’s going to happen to you in the South? Goin’ catfishin’?”

She shrugged. “The flag can mean pride to some people, I guess, and hate to others. I guess our pride in that flag can be as strong as some people’s hate.”

Carla Guy was also suspended for wearing the flag to school, and her mother Jean was one of the bus drivers fired. They sat on the couch in their mobile home, Carla in a Yale t-shirt, Jean in bunny slippers, a Confederate flag flying on the pole out front.

“Blacks think the flag means slavery, but it doesn’t mean that to me,” Carla says. “I just thought since I was born in the South, it was OK for me to wear the flag. I’m proud to be here, and the flag represents the South.”

What makes the South special? “Well, for one thing, we cook fried chicken, grits and gravy,” says Jean.

Carla nods. “The way we talk, I guess. Really, it all goes back to wars and things like that. To Robert E. Lee. Of course, I’m not really proud of the things he done, but he represented the South. I’m proud, but I guess he surrendered because he thought it was the best thing to do. We learned about the Civil War in the eighth grade, but I can’t remember why it was fought. I think it was to free the slaves, wasn’t it?”

Jean retrieves a tattered nylon flag from the closet. “I always had them since I was like a teenager,” she explains. “My sister has one in her front yard, too. I’ve always had the Confederate flag license tag on my car. That’s just us.”

Jean’s eldest daughter, Alesia Keith, sat in her lawyer’s office with Kenneth White, the third bus driver fired for wearing the Confederate flag. White is a close friend of hers. He is also black.

“You just don’t go telling people they can’t wear their Confederate flags,” says Keith. “People been wearing them since before I was born. I buy them for my children. I’ve had them since I was wee-little. My momma would give it to me and say, ‘You’re going to wear it,’ and that was that.”

White laughs. “Jean gave me a cap with a Confederate flag patch on it, and I wore it. So she must be the Klan leader.”

Keith nods, deadly serious. “Oh yeah, she’s a regular Grand Dragon. We keep our sheets starched.”

“To me, the flag don’t mean racism,” says White, 21. “This is a new day, and we’re just trying to get along. Bringing up the past don’t help none. You gotta take it like it comes. One day we will overcome — when we get rid of all these old people who keep bringing it up.”

“You have racism anywhere you go,” adds Keith. “You don’t have to be a member of the Klan to be a racist pig, and you don’t have to live down South to be a racist. What about the American flag? What do you think all the Japanese people who live here think when they see the American flag? This is their home, and this is my home. To me, the South is everybody I know, everybody I deal with on a day-today basis. I think Ken and I are the best example of how you can get along, no matter what color you are.”

Eugene Eder has been making flags for 40 years in Oak Creek, Wisconsin. The family firm, Eder Rag, sells $10 million worth of Confederate flags every year. They range in price from $10.10 for tiny indoor flags to $394 for giant outdoor models.

“The past four or five years it’s probably sold better than ever,” Eder says. “My own feeling is that it’s probably a form of rebellion — a backlash against blacks. That’s what I think. Some Southern states want to do away with the Confederate symbol, and some people want to rebel against that

“It does bother me, but I’m a purveyor of flags,” he says. “I suppose if you were completely honest you wouldn’t sell it. I refuse to sell the Nazi flag and the Japanese flag — flags where heinous crimes were committed. But the Confederate flag has such popular acceptance. A lot of people use it without any racial connotations. It was the flag of the Confederacy, after all.”

Claude Hayne has no such qualms. Sitting in his office at the National Capital Rag Company in Alexandria, Virginia, not far from where Colonel Ellsworth met his untimely end, Hayne sips his morning coffee and checks the latest sales records. He has sold only three Confederate flags in the past month.

“It doesn’t bother me to sell it,” Hayne says. “The media has used the racial issue to stir up trouble for a long time. They go overboard saying the Civil War was about slavery. That damn war ended 100 years ago, and it seems to me the media ought to let us forget it. I know Sons of Confederate Veterans who are red, white and blue USA through and through. They don’t want to turn the clock back 100-and-some years. And I certainly don’t, either.”

State Representative John Buskey was one of the Alabama lawmakers arrested for trying to take down the Confederate flag. “We all thought it was just a travesty having it flying over the state capitol,” he says. “It gives the state a negative image. It says that blacks are still second-class citizens.”

Buskey acknowledges that “there probably are some people who don’t see the flag as racist, but I don’t think they understand the significance of the flag. To us, it’s a symbol of racism. They used it during the Civil War, and it is a part of history. Now we ought to put it where it belongs — in a museum.”

Lillian Jackson, president of the Montgomery NAACP, agrees. “The Confederate flag has a place in American history — a place you cannot erase — but it has no place over the seat of government. You cannot say you support the flag of a war that was fought to enslave people and then say you are against slavery. That doesn’t make sense.”

It doesn’t make sense — yet many well-meaning white folks raise the flag every morning without giving slavery a moment’s thought. Never mind that the Confederate flag represented a land that enslaved four million Southerners. To them, the flag means good manners and noble ancestors and a determination to fight for your family. Like a child with a bad report card, they proudly present their “A” for appearance and hope no one will notice their “F’ in history.

“I don’t think the average ninth grader knows what the Civil War was fought over,” says Nikki Parkstone, who dropped out of school and got married the year after the flag controversy. “Somebody has got to tell them. If they learn it in a prejudiced way, then that’s the adults’ fault. The adults only have themselves to blame.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.