Headed for a Crash

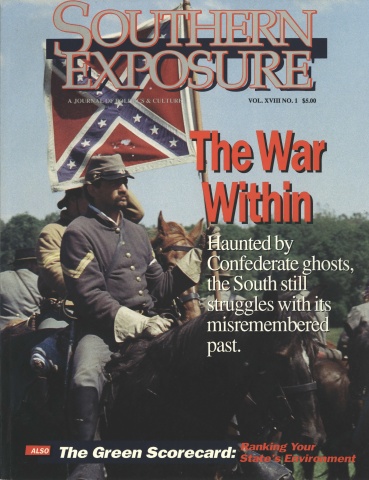

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

Baton Rouge, La. — Joe Hubbard is having a bad month.

His workload has quadrupled. Every day he receives dozens of calls from worried automobile drivers who have just learned that their insurance company, Louisiana-based Champion Insurance, has been declared insolvent. “This job wasn’t created to be full-time,” Hubbard complains. “But it is now.”

Since June, Hubbard has paid out more than $9 million in claims to 5,500 policyholders of the failed company, once the state’s third largest auto insurer. Hubbard’s employer, the Louisiana Insurance Guaranty Association, reckons that at least another $125 million is due some 38,000 additional claimants.

Newspaper reporters have been calling Hubbard nonstop for three weeks. “Who is going to pay for these pay-outs?” they ask. “You and me,” Hubbard responds. “The taxpayers.”

Over the next eight years, officials estimate, the Champion failure will deplete state treasuries in Louisiana, Alabama, and Tennessee by over$200 million. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. According to a six-month study by the Southern Finance Project, a non-profit research center based in North Carolina, Americans have already swallowed over $2.5 billion in losses from property and casualty insurance insolvencies since 1969. Three-quarters of those losses have occurred in the past six years — and Southern taxpayers have been stuck with a third of the bill.

Like the savings and loan industry before it, the insurance industry appears headed for a crash — and like the S&L crisis, the system is set up to pass the buck to average taxpayers and consumers. The latest round of insolvencies has already overwhelmed the tenuous system that protects policyholders, yet most regulators remain totally unprepared for what may be America’s next big financial crisis.

Silent Bailouts

The potential losses are staggering. Nationwide, over 2,000 property and casualty insurers hold combined assets of roughly $450 billion. In 1988 alone they sold roughly $200 billion in policies, insuring customers against everything from car crashes and workplace accidents to toxic waste liability and nuclear disasters.

Like banks and other financial intermediaries, insurance companies profit by collecting money in small amounts and investing or lending it in large amounts. Unlike banks and S&Ls, however, insurers are regulated by the states. When an insurance company goes bankrupt, policyholders are protected not by the U.S. Treasury, but by a complicated state-by-state system of guaranty associations, administered by the industry and paid for by taxpayers and consumers.

State legislatures created the associations in the 1970s after an unsuccessful attempt in Congress to establish a national guaranty fund similar to the one that protects depositors in the nation’s banks and savings and loans. To avoid federal control, the industry convinced states to let it clean up after its own insolvencies, without government help. When a company failed, the guaranty association would assess all the other insurers selling similar kinds of policies a fee to cover the claims of the failed company’s policyholders.

There was a catch, though: All the states allowed insurance companies to pass on the fees to taxpayers and policyholders. In Alabama, Louisiana, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia, insurers simply subtract the amount of the assessments from what they owe in state taxes. In the remaining Southern states, companies can raise their premiums to recoup the amount of the assessments.

In effect, the states set up a system of “silent bailouts,” making an unsuspecting public pick up the tab for insurance failures. As long as insolvencies were small and infrequent, the system worked pretty well. After all, the cost of paying off claims was rarely more than a tiny fraction of the total income of the industry.

But in the 1980s, a severe downturn hit the industry. Between 1984 and 1986, 58 companies went belly-up, compared to only 19 during the previous three years. The state guaranty funds — many of them staffed by part-time claims adjusters — were suddenly swamped with claims.

In the South, the assessments mounted at a staggering pace. Between 1985 and 1988, insurance bailouts cost almost three times more than they did during the previous 14 years combined. Even after accounting for inflation, the numbers are mind-numbing. Assessments skyrocketed by more than tenfold in five states and the District of Columbia, including an increase of 7,920 percent in North Carolina. In just four years, insurance failures cost more than $211 million in Florida and $111 million in Texas. (See chart.)

“The most troublesome part is that the public doesn’t even know what’s already hit them,” says Billy Lovett, a Georgia public service commissioner who is running for state insurance commissioner. “You can call what’s happened already a crisis.”

Incompetency Tax?

Whatever you call it, the dramatic rise in insurance insolvencies seems a lot like deja vu. Recent Congressional hearings into the failures of Transit, Mission, and Integrity — three large insurers with policyholders in nearly all 50 states — uncovered a pattern of fraud and abuse eerily familiar to the rampant wheeling and dealing that triggered the collapse of the savings and loan industry.

Many smaller companies failed because they simply tried to grow too fast, using scores of outside “managing general agents” to boost their volume of new policies. Industry insiders say the boom in new policy sales was part of a strategy called “cash-flow underwriting,” the practice of selling too many policies and plowing the money into risky, high-yield investments. Last year the industry earned a record $31.5 billion in investment income, more than offsetting its $21.5 billion in underwriting losses.

In essence, insurers have been gambling with policyholders’ money, betting that investment gains will keep pace with claim payments. Similar reckless money management by high-flying S&Ls helped touch off the largest financial calamity in U.S. history.

When the insurance fiasco picked up steam in the mid-1980s, no one was prepared — least of all the state guaranty funds that were supposed to protect policyholders. Paul Gulko, a guaranty-fund specialist who began overseeing the Virginia association in 1983, says he found it being run by “a part-time claims man who was working out of his trunk.” It was almost impossible to pay off claims from failed companies, he adds, because “the records are terrible. They don’t know who is insured with them. Their database is hopelessly out of order.”

While the understaffed guaranty funds try to cope with the sudden surge of insolvencies, regulators for the most part remain on the sidelines. Many complain that they lack the resources or the authority to stem the tide of failures. But the real problem, says Georgia’s Billy Lovett, is that regulators simply lack the political will to challenge the industry.

“It’s an outrage,” he says. “If the public knew about this, they would want to hang someone. Maybe we should start calling insolvency assessments ‘fraud taxes’ or ‘incompetency taxes.’”

Hush-Hush Slush

Sometimes, lawmakers say, the problem isn’t lax regulation — it’s outright complicity between regulators and the very industry they are supposed to be monitoring. Take Louisiana, for example. Just four months before Champion’s collapse last June, state insurance commissioner Doug Green released an audit giving the company a clean bill of health. Champion executives, meanwhile, were busy transferring company assets to a holding company in an attempt to keep them out of the hands of liquidators. A few weeks after Green declared Champion insolvent, the state ethics commission began an inquiry into allegations that the owners of Champion’s holding company had secretly funneled more than $2 million to Green’s campaign chest.

In July, news reports surfaced that Champion’s computer database had been mysteriously erased, depriving guaranty fund managers of the records they needed to pay off policyholders.

Kay Doughty, chief counsel for consumer affairs with the Texas Board of Insurance, agrees that regulators could do a better job detecting and preventing insolvencies. Back in 1986, her office noticed a rapid increase in complaints from the policyholders of National County Mutual, a large insurer that specialized in “high risk drivers” who had been turned down by other insurers. Concerned that National County’s delinquency in paying claims might indicate that the company was having serious financial problems, Doughty alerted state auditors.

“When I first brought it up, National County was in the hole by about 15 to 20 million dollars,” she recalls. “By the time they did anything about it, the price tag was upwards of $50 million.”

A subsequent investigation by state Senator John Montford concluded that National County had falsified two annual reports and may have illegally diverted more than $25 million in premiums to outside concerns. The investigation also revealed that the state Board of Insurance was fully aware of these facts for over a year before it placed the company into receivership.

While Senator Montford was conducting his investigation in Texas, Georgia legislator Bud Stumbaugh was walking across his state to drum up support for a slate of insurance reforms. Stumbaugh, who chairs the senate insurance committee, says that most Georgians are “totally unaware” that they pay the price for insurance insolvencies.

“In Georgia, the regulators are hush-hush about anything that has a hint of negativism,” Stumbaugh laments. “A lot of times, our committee doesn’t even know what needs to be done.”

Even when he does know what needs to be done, Stumbaugh faces a formidable insurance lobby that has repelled nearly every substantive insurance reform initiative in Georgia for the past 50 years. It was easier for Stumbaugh to walk the backroads of the state than to walk his reform package through the state legislature. In fact, most of his reforms never made it out of the committee he chairs.

Shady Sunshine State

Walter Dartland didn’t walk across Florida to communicate his message of reform, but he did run for insurance commissioner. Since 1971, insurer insolvencies have cost Florida consumers $356 million — far more than policyholders have borne in other Southern states. Guaranty fund officials say Florida suffers higher insolvency costs because the state attracts hundreds of small, poorly capitalized companies vying to sell insurance policies to the growing population of older, more affluent Floridians.

But Dartland insists that “the real problem is political.” He and others claim the recent failure of Industrial Casualty, one of the largest insolvencies in Florida, could have been prevented if regulators had acted sooner. A full year before it was declared insolvent, Industrial Casualty hired the former general counselor of the state Department of Insurance to lobby on its behalf. According to Dartland, “He convinced the commissioner not to do anything about the problems.” Those problems eventually cost Florida consumers over $60 million.

In the course of his unsuccessful campaign for insurance commissioner, Dartland discovered another way that the industry exerts its influence over regulators. Dartland managed to raise about $100,000 in campaign funds, mostly from small contributors who shared his reform sentiments. He also became the first candidate ever to get matching funds from the state of Florida. But his two opponents in the primary raised over $800,000 each — most of it from insurance companies.

“The way the campaign finance laws work, a company can give and each of its employees can give,” he explains. “We figured that all together, each company could get about $30,000 or $40,000 in the hands of its choice for insurance commissioner.”

Treasuries and Cheese

Ask just about any insurance executive to assess the way regulators have handled the industry’s insolvencies, and chances are he’ll point to the $300 billion S&L crisis to show how the $2.5 billion blowout in property and casualty insurance pales by comparison. But an increasing number of Southern lawmakers are beginning to see cause for alarm. After all, the S&L crisis isn’t draining state treasuries of hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenue. The property and casualty insolvencies are.

Over the next eight years, the Champion failure alone will rob Alabama of roughly $50 million, Tennessee of at least $10 million, and Louisiana of $135 million. The Louisiana Insurance Guaranty Association — which is currently paying policyholders of insolvent insurers $6.5 million a month in claims — predicts that an additional $44 million will be paid out as a result of eight other pending insolvencies.

In December 1989, the Louisiana association warned a state legislative subcommittee that it would run out of money in two months. To continue paying off claims, fund managers reported, lawmakers would have to either increase the maximum amount that insurers can be assessed each year, appropriate money directly to pay out the remaining claims, or levy a surtax on policyholders.

The Champion failure couldn’t have come at a worse time for Louisiana. Officials predict an $855-million budget shortfall for the coming fiscal year. Still reeling from the collapse of the oil economy in the mid-1980s, the state now faces the prospect of a tax overhaul whose major proponent, Governor Buddy Roemer, acknowledges will transfer much of the tax burden from big corporations to average citizens.

Texas has also been hard hit by the collapse of the oil economy — and big insurance insolvencies. The legislature recently enacted substantial tax increases to avoid a budget crunch. The state Board of Insurance, meanwhile, expects insurers to “offset” or deduct $40 million from their 1989 state taxes and $57 million in 1990 — nearly twice what Texas spent in 1988 to distribute cheese and other surplus food to hungry families.

Staff members for Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby predict those losses will be much higher. Concerned about open-ended taxpayer liability and a record number of insurance insolvencies, Hobby’s staff has begun a study of the overall effect of the tax offsets on the state budget. “The big fear,” says Jose Camacho, an aide in charge of the forthcoming report, “is that the guaranty fund won’t be able to handle the losses and the state will be left holding the bag.”

“Nothing’s Being Done”

By all indications, that bag is going to get much bigger in the next few years. With the insurance industry’s increased reliance on investment income, a mild recession could push many firms over the brink of insolvency. “Hang on to your hats,” warns Kay Doughty, the Texas consumer counsel. “The costs of insolvencies are still going up.”

In the South, the industry’s prospects look particularly bleak. According to Insurance Forum magazine, over 300 property and casualty insurance companies are currently in trouble nationwide. Ninety-eight of the firms on the “watchlist” are headquartered in the South, most of them in Texas and Florida.

Recent disasters have only made things worse. The $4.1 billion price tag on Hurricane Hugo last year contributed to the insolvency of two small South Carolina insurers and may have weakened others. And the explosion of a Phillips Petroleum plant in Pasadena was one more blow to the already shaky insurance industry in Texas.

But most of the money Southerners are paying for insolvencies results from failures by insurance companies headquartered outside the region. In 1987 and 1988, for example, 79 percent of all assessments by Southern guaranty funds stemmed from non-Southern insolvencies. The failures of the Transit, Mission, and Integrity companies based in California and Missouri accounted for $108 million of all Southern assessments — one-fifth of the region’s total losses between 1985 and 1988.

Yet many regulators continue to stand by and do nothing. “I’m no expert, but right now I could tell regulators six companies that are going broke this year,” said one manager of a Southern guaranty fund who asked not to be identified. ‘These companies ought to be jumped on. But nothing’s being done.”

Voter Revolt

The big fear for the insurance industry is that the public will lose patience with the growing number of “silent bailouts.” Privately, many industry insiders argue that the only way to stem the tide of insolvencies is for the industry to raise rates

substantially. But consumer advocates like Rob Schneider of the Texas Consumers Union say insurance companies that are losing money have only themselves to blame. “In Texas,” he says, “you’re guaranteed a profit unless you’re a complete fool.”

The crisis is attracting attention on Capitol Hill, where some members of Congress have called for the repeal of the McCarran-Ferguson Act, the law which exempts insurance companies from antitrust provisions and prohibits federal regulation of insurance.

Industry lobbyists already have their hands full in the state legislatures trying to contain the growing movement for rate reform that began when Californians voted for a 20 percent rollback in insurance rates in 1988. According to Voter Revolt, a grassroots group that spearheaded the California initiative, similar rate reform campaigns are now underway in 35 states.

Texas State Representative Eddie Cavazos thinks that the groundswell of grassroots activity around rate reform reflects a fundamental transformation in the way the public regards the insurance industry. According to Cavazos, citizens are beginning to look at insurance as “a public commodity like utilities.”

“It is not a product that you buy because you want it,” he says. “It is a product you are required to have.”

Cavazos, who recently championed a 12-point insurance reform initiative in Texas, supports repeal of the McCarran-Ferguson Act. But he insists that only tougher state regulation will protect taxpayers and insurance consumers. He and others cite the “atmosphere of secrecy” that surrounds the industry and those who regulate it. Most state insurance boards examine company books less than once every three years, and 12 Southern states do not disclose the names and financial status of troubled insurers.

Cavazos says that unless states move quickly to monitor insurance companies, taxpayers could face a bill of staggering proportions. “If we don’t start regulating the insurance industry,” he warns, “we will have S&L Crisis Part II.”

Tags

Marty Leary

Marty Leary is research director of the Southern Finance Project, a non-profit organization sponsored by the Institute for Southern Studies. (1992)