This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

There’s much to be said for picking up the trash. And for planting a tree, recycling our newspapers, and avoiding styrofoam. With the 20th anniversary of Earth Day on April 22, we’re hearing a lot about what we can do, each one of us. After all, we’re either part of the problem or part of the solution.

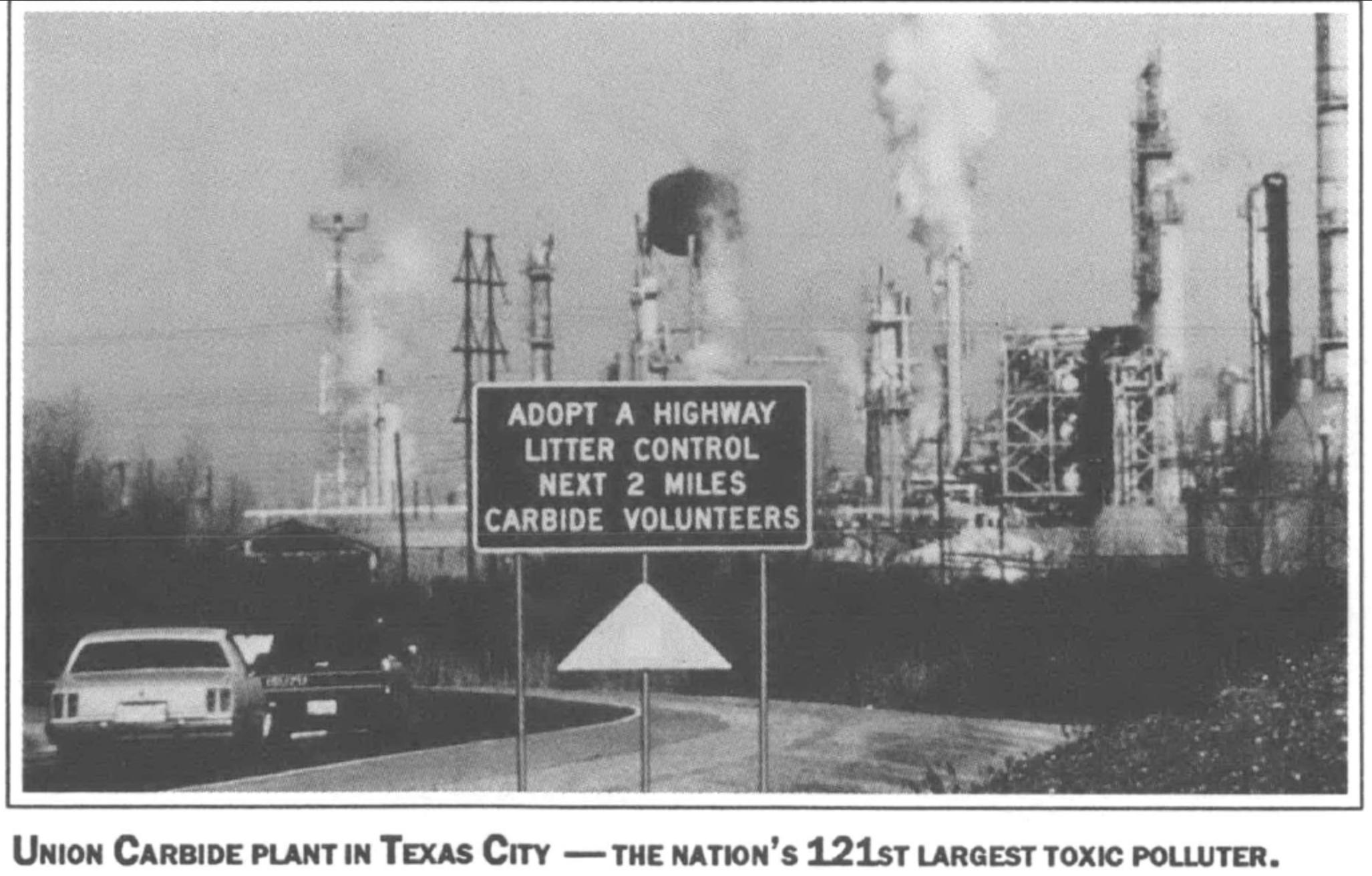

But there’s also something to be said for scale. Your trash and mine pale in comparison to the surge of garbage spewed from the Union Carbide factory pictured here in Texas City, Texas. Each week, the plant pours 200,000 pounds of chemicals into the air, making it number 121 on the Environmental Protection Agency list of the nation’s biggest toxic polluters.

“I call this Toxic City,” says Rita Carlson, a Texas City native who lives 12 blocks from Carbide. “We have eight plants like this one here, and 29 lined up along Galveston Bay to Houston.

“We’re told that what they make — the plastics, pesticides, oil products — is essential to the nation, and that we shouldn’t worry,” she continues. “But I say this is a national sacrifice zone. If people don’t wake up to what’s happening along the Texas and Louisiana coast with all these chemicals, we’re going to lose the nation. The air we all breathe comes from the ocean, and that’s where this waste is going.”

Give Carlson a few minutes and she can put the “Litter Control” sign outside Carbide’s gate into proper perspective. A pool of groundwater tainted by 35 chemicals has left the plant and is headed for parts unknown. At another site, Texas officials estimate that Carbide has contaminated water supplies with more than 700,000 barrels of poisons. Meanwhile, the company distributes slick bulletins as part of its “good neighbor” program, assuring people that it cares about the environment, too. Just look how clean it keeps the highway it adopted.

“We’ve got to stop this nonsense and start getting to the nitty gritty,” says Carlson. “There could be a 90-percent reduction of what these companies discharge, using methods already available — if they would make the commitment.”

Homegrown Resistance

Why don’t giant companies like Carbide take every available step to reduce their toxic littering? Or, better yet, why don’t they devote their expansive public relations talents toward selling America on clean, healthful alternatives to chemical byproducts?

Part of the reason goes back to the matter of scale. When we try to propose solutions, the discussion narrows to an issue of “personal convenience.” And when we try to point to the problems, the talk turns to technical debates over what constitutes an “acceptable risk level” to this or that species of snail darter.

Measuring the emissions — and omissions — of firms like Union Carbide is concrete enough. But evaluating the overall condition of our environment is far more elusive. What about the health of Rita Carlson’s children, who doctors say have abnormal lymph glands and a “strange” blood disorder? What about the health of the workers in the paper industry, which has an illness and injuries rate 50 percent higher than the national average? And what about the fate of the invariably poor, usually black communities that hug the edge of America’s toxic factories?

Fortunately, ordinary citizens like Carlson have made the connections between disappearing snail darters and the health of their children. It’s not the unknown they worry about; it’s what they do know that keeps them going. Because of their efforts — often belittled as a “not in my backyard” psychosis — new energy has flowed into the environmental movement. It now has the potential to be a truly mass movement one that engages farmers and mothers, jobholders and the jobless, lovers of our coasts and dwellers in our toxic slums.

To reinforce these ties, the Institute for Southern Studies has developed a Green Scorecard that measures the relative rank of the 50 states using a comprehensive approach to environmental health. It recognizes, as do the Greens in Europe, that vital connections exist between economic justice, public health, and environmental integrity. A society that sacrifices one of these risks losing them all. Public and private policymakers who undervalue one ultimately jeopardize the others.

Nowhere are the interrelations more plainly visible than here in the South. The reason has less to do with the fact that the region is poor than with the legacy of policymakers who promote the proposi-

tion that everything in the South is cheap — available for the taking, no questions asked. As the articles in this section demonstrate, this historic economic development policy has produced a devastated environment, inequitable tax structure, and corrupt politicians — as well as a brand of homegrown resistance that offers enormous potential for change.

At the Bottom

According to the Scorecard, the Northeast and Great Lakes regions score poorly on our Poisons Index, which ranks standard measures of pollution like air quality and the per capita number of Superfund toxic waste sites. But many of these same states have abandoned development strategies that sell themselves short. Relying on a relatively educated population and a higher standard of public accountability, they have taken aggressive actions to address their problems. As a result, they score highest on the index we created to evaluate innovative policies and energetic political leadership. They also do well on our Worker Health Index, which includes a review of state laws protecting workers graded by the Southern Labor Institute of the Southern Regional Council.

By comparison, states in the Mountain region score very poorly in nearly all areas related to government initiative and planning, holding fast to the frontier belief that the less regulation, the better. Fortunately for them, they don’t have the pollution levels of other regions, although their rapidly increasing economic reliance on minerals and other natural resources promises escalating trouble.

Of all the regions, only the South maintains a backward resistance to environmental problems in the face of extraordinary levels of poisons. In a ranking of states from 1 to 50, Southern states take the bottom slots in every Index on our Green Scorecard.

The region has six of the ten states with the highest per capita amounts of toxic chemical discharge, seven of the ten producing the most hazardous waste, 92 of the 149 facilities that pose the greatest risk of cancer to their neighbors, and 30 of the top 100 industrial sources of ozone-depleting chemicals.

The South also has six of the ten states with the highest unemployment rates, seven of the ten with the lowest rates of health insurance protection, and nine of the ten with the highest rates of premature deaths. Ten of the South’s 13 states already have above average incident rates of cancer, and we’re catching up fast with the higher rates of the more poisoned Rustbelt.

The numbers should make anyone question the wisdom of our leaders’ traditional approach to economic development. Yet the February edition of Site Selection magazine still brims with ads from Southern recruiters enticing manufacturers to take advantage of Florida’s “overabundance of land and virtually non-unionized labor force,” Mississippi’s “old-fashioned work ethic and refreshing spirit of cooperation,” Georgia’s “one-stop environmental permitting convenience,” and Kentucky’s “low land costs and tax incentives.”

Brown Is Beautiful

In a political climate where the South’s people and environment are so shamelessly peddled to major manufacturers, industry has no incentive to search for cleaner alternatives. Some of the most dangerous polluters in the South today are the giant paper companies like International Paper. These huge firms produce dioxin — one of the deadliest chemicals in the world — as they turn wood pulp into bleached white paper. The colossus IP mill in Georgetown, South Carolina rains corrosive dust on homes in the nearby black community and its Booker T. Washington Community Center.

With its vast resources, the company could easily adopt techniques already used in parts of Europe to reduce dioxin. Better yet, it could cut back the bleaching and start marketing brown milk cartons, envelopes, paper plates, and toilet paper under the slogan that “Brown is Beautiful.” Instead, International Paper and the rest of the industry are pressuring Southern states to relax their meager dioxin standards.

Faced with such gigantic adversaries, the South’s homegrown environmental pioneers have much to fight — and much to offer the rest of the nation. From Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, who have linked demands for fair taxes and fair land-use, to the interracial coalition leading its second Great Toxics March in Louisiana, practical wisdom and vision is all around us. Grassroots leaders like Rita Carlson have made environmental justice a mainstream issue, attracting widespread support and a growing number of political opportunists.

The challenge remains one of scale. We can’t let our efforts be confined by small-minded solutions for misnamed problems. We must continue making the connections between pollution and disease, between poisons and poverty, between racism and the politics of siting dangerous factories and toxic dumps. We must keep building in our communities, but we must also knit our local protest groups into a collective enterprise capable of reshaping the terms of environmental debate.

In a society dominated by large-scale enterprises, we know it’s not enough to simply clean up the mess — “waste management” and “litter control” won’t solve the problem. Positive action requires stopping the mess before it happens, a radical change in production and marketing, thinking and doing. This Earth Day, and every day thereafter, let’s pick up after ourselves, but let’s also keep naming names, promoting bold programs, and building a stronger movement to define life as we would like it for ourselves and our children.

Tags

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.